HMS Pinafore Itself and the Associateci Topics That This Thesis Examines Is Not Particularly Abundant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com SirArthurSullivan ArthurLawrence,BenjaminWilliamFindon,WilfredBendall \ SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. From the Portrait Pruntfd w 1888 hv Sir John Millais. !\i;tn;;;i*(.vnce$. i-\ !i. W. i ind- i a. 1 V/:!f ;d B'-:.!.i;:. SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN : Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. By Arthur Lawrence. With Critique by B. W. Findon, and Bibliography by Wilfrid Bendall. London James Bowden 10 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.C. 1899 /^HARVARD^ UNIVERSITY LIBRARY NOV 5 1956 PREFACE It is of importance to Sir Arthur Sullivan and myself that I should explain how this book came to be written. Averse as Sir Arthur is to the " interview " in journalism, I could not resist the temptation to ask him to let me do something of the sort when I first had the pleasure of meeting ^ him — not in regard to journalistic matters — some years ago. That permission was most genially , granted, and the little chat which I had with J him then, in regard to the opera which he was writing, appeared in The World. Subsequent conversations which I was privileged to have with Sir Arthur, and the fact that there was nothing procurable in book form concerning our greatest and most popular composer — save an interesting little monograph which formed part of a small volume published some years ago on English viii PREFACE Musicians by Mr. -

Vol. 17, No. 4 April 2012

Journal April 2012 Vol.17, No. 4 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] April 2012 Vol. 17, No. 4 President Editorial 3 Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM ‘... unconnected with the schools’ – Edward Elgar and Arthur Sullivan 4 Meinhard Saremba Vice-Presidents The Empire Bites Back: Reflections on Elgar’s Imperial Masque of 1912 24 Ian Parrott Andrew Neill Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Diana McVeagh ‘... you are on the Golden Stair’: Elgar and Elizabeth Lynn Linton 42 Michael Kennedy, CBE Martin Bird Michael Pope Book reviews 48 Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Lewis Foreman, Carl Newton, Richard Wiley Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Leonard Slatkin Music reviews 52 Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Julian Rushton Donald Hunt, OBE DVD reviews 54 Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Richard Wiley Andrew Neill Sir Mark Elder, CBE CD reviews 55 Barry Collett, Martin Bird, Richard Wiley Letters 62 Chairman Steven Halls 100 Years Ago 65 Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed Treasurer Peter Hesham Secretary The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Helen Petchey nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Arthur Sullivan: specially engraved for Frederick Spark’s and Joseph Bennett’s ‘History of the Leeds Musical Festivals’, (Leeds: Fred. R. Spark & Son, 1892). Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. -

The Mikado the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival The Mikado The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Erin Annarella (top), Carol Johnson, and Sarah Dammann in The Mikado, 1996 Contents Information on the Play Synopsis 4 CharactersThe Mikado 5 About the Playwright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play Mere Pish-Posh 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: The Mikado Nanki-Poo, the son of the royal mikado, arrives in Titipu disguised as a peasant and looking for Yum- Yum. Without telling the truth about who he is, Nanki-Poo explains that several months earlier he had fallen in love with Yum-Yum; however she was already betrothed to Ko-Ko, a cheap tailor, and he saw that his suit was hopeless. -

Or, the Witch's Curse!

Ruddygore or, The Witch's Curse! An Entirely Original Supernatural Opera in Two Acts Written by W. S. Gilbert Composed by Arthur Sullivan First produced at the Savoy Theatre, London, Saturday 22nd January 1887 under the management of Mr. Richard D'Oyly Carte This edition privately published by Ian C. Bond at 2 Kentisview, Kentisbeare, CULLOMPTON. EX15 2BS. © 1995 RUDDYGORE Of all the Gilbert and Sullivan joint works, RUDDYGORE has been the most unfairly treated. The initial, rather hostile reception, led the partners to make a number of cuts and changes which, under rather more favourable circumstances, would probably not have been so severe. This gradual dissection continued in the 1920’s at the hands of Geoffrey Toye, Harry Norris, Malcolm Sargent and J M Gordon until, by the post-war revival of 1949, RUDDIGORE was, to all intents and purposes, a new work. It is to be hoped that such a thing could not happen today as I would like to think that we have far too much respect for the works of these two men to allow anyone to take such drastic rewrites upon themselves. That the original version of the opera works is evidenced by the considerable number of amateur revivals over the past few years that have attempted to return as closely as possible (given the lack of performing material) to a ‘first night version’ - a trend fuelled by the New Sadler’s Wells revival of 1987. That Gilbert was guilty of one miscalculation is fairly obvious in his placing of “The battle’s roar is over” in Act One. -

The Pirates of Penzance NOTE: the Articles in These Study Guides Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Particular Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival The Pirates of Penzance NOTE: The articles in these study guides are not meant to mirror or interpret any particular productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to under- standing and enjoying the play (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters at times) may differ from what is ultimately produced on stage. Also, some of these articles (especially the synopses) reveal the ending and other “surprises” in some plays. If you don’t want to know this information before seeing the plays, you may want to reconsider studying this information. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Laurie Birmingham (left) and Glenn Seven Allen in The Pirates of Penzance, 2001. Contents Information on the Play Synopsis 4 TheCharacters Pirates of Penzance5 About the Playwright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play Preserving the Truly Good Things in Drama 8 Delighting Audiences 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: The Pirates of Penzance On the coast of Cornwall, a gang of pirates play and party as Frederic (a pirate apprentice) reminds the pirate king that his obligation to the gang is soon over. -

The Farces of John Maddison Morton

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 The aF rces of John Maddison Morton. Billy Dean Parsons Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Parsons, Billy Dean, "The aF rces of John Maddison Morton." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1940. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1940 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARSONS, Billy Dean, 1930- THE FARCES OF JOHN MADDISON MORTON. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Speech-Theater University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan © 1971 BILLY DEAN PARSONS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE FAECES OF JOHN MADDISON MORTON A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Speech / by Billy Dean Parsons B.A., Georgetown College, 1955 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1958 January, 1971 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express his deep appreciation to Dr•Claude L« Shaver for his guidance and encourage ment in the writing of this dissertation and through years of graduate study• He would also like to express his gratitude to Dr. -

GILBERT and SULLIVAN PAMPHLETS† Number Two

1 GILBERT AND SULLIVAN PAMPHLETS † Number Two CURTAIN RAISERS A Compilation by Michael Walters and George Low First published October 1990 Slightly revised edition May 1996 Reprinted May 1998. Reformatted and repaginated, but not otherwise altered. INTRODUCTION Very little information is available on the non Gilbert and Sullivan curtain raisers and other companion pieces used at the Savoy and by the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company on tour in their early years. Rollins and Witts give a brief list at the back of their compilation, and there are passing references to some of the pieces by Adair-Fitz- gerald and others. This pamphlet is intended to give some more data which may be of use and interest to the G&S fraternity. It is not intended to be the last word on the subject, but rather the first, and it is hoped that it will provoke further investigation. Perhaps it may inspire others to make exhaustive searches in libraries for the missing scores and libretti. Sources: Cyril Rollins & R. John Witts: 1962. The D’Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas. Cyril Rollins & R. John Witts: 1971. The D’Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas. Second Supplement. Privately printed. p. 19. J.P. Wearing: 1976. The London Stage, 1890-1899. 2 vols. J.P. Wearing: 1981. The London Stage, 1900-1909. 2 vols. Allardyce Nicoll: A History of English Drama 1660-1900, vol. 5. (1959) Late Nineteenth Century Drama 1850-1900. Kurt Ganzl: 1986. The British Musical Theatre. 2 vols. S.J. Adair-Fitzgerald: 1924. -

H.M.S. Pinafore

H.M.S. PINAFORE or, The Lass that loved a Sailor An entirely Original Nautical Comic Opera Written by W.S. Gilbert Composed by Arthur Sullivan Rescued from Obscurity A Reprint series of Definitive Libretti of the „Savoy‟ and related operas. Edited by Ian C. Bond. Other Libretti in this Series AN ITALIAN STRAW HAT, or, “Haste to the Wedding” W.S. Gilbert, George Grossmith, et al. COX AND BOX - F.C. Burnand and Arthur Sullivan CREATURES OF IMPULSE - W.S. Gilbert and Alberto Randegger THE EMERALD ISLE - Basil Hood, Arthur Sullivan and Edward German FALLEN FAIRIES - W.S. Gilbert and Edward German THE GONDOLIERS - W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan “HASTE TO THE WEDDING” - W.S. Gilbert and George Grossmith JANE ANNIE - J.M. Barrie, Arthur Conan Doyle and Ernest Ford NO CARDS - W.S. Gilbert and Thomas German Reed THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE - W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan PRINCESS TOTO - W.S. Gilbert and Frederic Clay THE ROSE OF PERSIA - Basil Hood and Arthur Sullivan RUDDYGORE - W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan UTOPIA (LIMITED) - W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan THE VICAR OF BRAY - Sydney Grundy and Edward Solomon THE ZOO - B.C. Stephenson and Arthur Sullivan Vocal Scores AN ITALIAN STRAW HAT, or, “Haste to the Wedding” W.S. Gilbert, George Grossmith, et al. THE EMERALD ISLE - Basil Hood, Arthur Sullivan and Edward German THE ROSE OF PERSIA - Basil Hood and Arthur Sullivan (facsimile of a cued conductors score) In Preparation THE BEAUTY STONE - Arthur Wing Pinero, J. Comyns Carr and Arthur Sullivan THE BRIGANDS - H. -

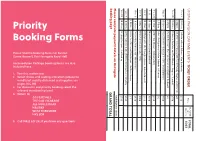

Priority Booking Forms

NUMBER TOTAL UTOPIA PAVILION DAYTIME EVENTS TICKET ORDER Price OF TICKETS COST Mon 9 10.30am Sullivan without Gilbert - Alan Borthwick £7.50 2.00pm An Afternoon of Opera with Sarah Helsby Hughes and Friends £15 Tues 10 10.30am Patience, Pinafore and The Mikado - Stephen Turnbull £7.50 2.00pm Double Bass with Matthew Siveter and Stephen Godward £15 Wed 11 10.30am Sex & Death in Victorian Theatre - David Wilmore £7.50 2.00pm Juliet Montgomery & Aiden Edwards in Concert £15 Thurs 12 10.30am A Monkey Shaved - Adrianne Berg £7.50 Fri 13 10.30am Masterclass with Donald Maxwell £7.50 Sat 14 10.30am D'Oyly Carte: Life through a Lense - Roberta Morrell £7.50 Sun 15 11.00am Church Service (Location TBC) FREE Mon 16 10.30am Discovering Princess Ida - Martin Yates £7.50 2.00pm A Source of Innocent Merriment - Matthew Siveter £15 Tues 17 10.30am Arthur Sullivan: A Life of Divine Emollient - Ian Bradley £7.50 Wed 18 10.30am Singing the Spas - Ian Bradley £7.50 Total Daytime events Please complete payment details on Harrogate booking page GRAND TOTAL GS FESTIVALS THE OLD VICARAGE ALL SOULS ROAD HALIFAX WEST YORKSHIRE HX3 6DR Call 01422 323 252 any questions if you have Select shows and seating allocation (please be mindful of socially distanced seating plans on pages 14 & 30) For discounts and priority booking select the relevant membership level to: Return Tear this section out Tear 5. 4. 3. 1. 2. Accomodation Package booking forms are also Package Accomodation included here. Opera House & The Harrogate Royal Hall Opera House & The Harrogate Royal -

Audienc E G Uide

AUDIENCE GUIDE 2017 - 2018 | Our 58th Season 1 2018 | Issue For our production of Hot Mikado, the Hot Mikado takes place in the Cabot Theatre is transformed into a Japanese town of Titipu, where a 1940s Harlem nightclub. Back then, young woman, (Yum-Yum), a you could expect to see top stars of wandering trumpeter, (Nanki-Poo) and the day, like Duke Ellington, Cab the Lord High Executioner, (Ko-Ko) Calloway and the Nicholas Brothers find themselves in a preposterous love with their dazzling tap routines. triangle. To add to the nonsense, Featured in our fictional nightclub is Katisha, the older fianceé of Hot Mikado, a cultural collision Nanki-Poo, is determined to between East and West with hip ‘40s re-capture him with the help of the IN THIS ISSUE American fashion blended with the Mikado. What ensues is a tangled web style and culture of old Japan. of typical Gilbert and Sullivan topsy-turvy confusion that will keep Hot Mikado History Hot Mikado is David H. Bell’s 1986 you wondering what’s next. adaptation of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Harlem classic operetta, which retains the Sullivan's great music is jazzed up in original's daffy plot and incisive 1940s style by arranger Rob Bowman. Synopsis political satire. “I think Skylight On stage, our Titipu Town Band keeps audiences will be thrilled by this the joint jumping with a sizzling score Gilbert and Sullivan updated version of Gilbert and that features jazz, swing, gospel, Glossary Sullivan’s comic masterpiece. It Be-Bop and blues. The action is remains true to their wonderful music nonstop with an energetic cast that and harmonies, but takes a fresh doesn't miss a beat in knockout approach to address some of the jitterbug, swing and foot stomping outdated dialog and stereotyping,” gospel dance routines that raise the said director Austene Van. -

Law's Lunacy: W.S. Gilbert and His Deus Ex Lege1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank \\server05\productn\O\ORE\83-3\ORE305.txt unknown Seq: 1 12-APR-05 10:55 Essay JEFFREY G. SHERMAN* Law’s Lunacy: W.S. Gilbert and His Deus ex Lege 1 I can teach you with a quip, if I’ve a mind; I can trick you into learning with a laugh; Oh, winnow all my folly, and you’ll find A grain or two of truth among the chaff! —W.S. Gilbert2 I ENTER MR. GILBERT udges often use the phrase “Gilbert & Sullivan” as a pejora- Jtive,3 invoking the Englishmen’s names to characterize ad- * Professor of Law, Chicago-Kent College of Law, Illinois Institute of Technology. B.A. ‘68, J.D. ‘72, Harvard University. I should like to thank Steven Heyman and Nancy Marder for their valuable suggestions and advice, and the Marshall D. Ewell Research Fund for its support. I owe a special debt of gratitude to Douglas Kahn, whose unexpected reference to Gilbert & Sullivan during an e-mail exchange pro- vided the inspiration for this Article. 1 Readers will recognize this Latin phrase as a play on deus ex machina (literally “god out of the machine”): an auctorial device—now much despised—whereby a character is providentially, though not always convincingly, introduced near the end of a play or novel for the sole purpose of rescuing the hero. Deus ex lege would mean “god out of the law,” suggesting a plot contrivance that relies on a law, rather than a person, to extricate the work’s characters from their predicament. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2020

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2020 This is the eighteenth year that MusicWeb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2019-November 2020). The 146 selections have come from 28 members of the team and 69 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources; I say that every year, but still the spread of choices surprises and pleases me. Of the selections, ten have received two nominations: • Eugene Ormandy’s Saint-Saëns Organ symphony on Dutton • Choral music by Jančevskis on Hyperion • Stephen Hough’s Beethoven concertos on Hyperion • Lutosławski symphonies on Ondine • Stewart Goodyear’s Beethoven concertos on Orchid Classics • Maria Gritskova’s Prokofiev Songs and Romances on Naxos • Giandrea Noseda’s Dalapiccola Il Priogioniero on Chandos • Les Kapsber'girls Che fai tù? on Muso • Edward Gardner’s Peter Grimes on Chandos • Véronique Gens recital Nuits on Alpha Hyperion was this year’s leading label with 16 nominations, and Chandos with 11 deserves an honourable mention. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve-month period, we published more than 2300 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year. Ludwig van BEETHOVEN Piano Concertos 1-5 - Stephen Hough (piano), Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Hannu Lintu rec. 2019 HYPERION CDA68291/3 It being a big Beethoven anniversary year, that seemed to provide a clue as to where to look for a choice.