The Snodgrass Tapes Facts and Theories on the Insect Head. Part 1. Robert Evans Snodgrass Page 1 FACT THEORY Figure 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Arthropod Groups What Is Entomology?

Entomology 340 Introduction to Arthropod Groups What is Entomology? The study of insects (and their near relatives). Species Diversity PLANTS INSECTS OTHER ANIMALS OTHER ARTHROPODS How many kinds of insects are there in the world? • 1,000,0001,000,000 speciesspecies knownknown Possibly 3,000,000 unidentified species Insects & Relatives 100,000 species in N America 1,000 in a typical backyard Mostly beneficial or harmless Pollination Food for birds and fish Produce honey, wax, shellac, silk Less than 3% are pests Destroy food crops, ornamentals Attack humans and pets Transmit disease Classification of Japanese Beetle Kingdom Animalia Phylum Arthropoda Class Insecta Order Coleoptera Family Scarabaeidae Genus Popillia Species japonica Arthropoda (jointed foot) Arachnida -Spiders, Ticks, Mites, Scorpions Xiphosura -Horseshoe crabs Crustacea -Sowbugs, Pillbugs, Crabs, Shrimp Diplopoda - Millipedes Chilopoda - Centipedes Symphyla - Symphylans Insecta - Insects Shared Characteristics of Phylum Arthropoda - Segmented bodies are arranged into regions, called tagmata (in insects = head, thorax, abdomen). - Paired appendages (e.g., legs, antennae) are jointed. - Posess chitinous exoskeletion that must be shed during growth. - Have bilateral symmetry. - Nervous system is ventral (belly) and the circulatory system is open and dorsal (back). Arthropod Groups Mouthpart characteristics are divided arthropods into two large groups •Chelicerates (Scissors-like) •Mandibulates (Pliers-like) Arthropod Groups Chelicerate Arachnida -Spiders, -

Segmentation and Tagmosis in Chelicerata

Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (2017) 395e418 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Arthropod Structure & Development journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/asd Segmentation and tagmosis in Chelicerata * Jason A. Dunlop a, , James C. Lamsdell b a Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science, Invalidenstrasse 43, D-10115 Berlin, Germany b American Museum of Natural History, Division of Paleontology, Central Park West at 79th St, New York, NY 10024, USA article info abstract Article history: Patterns of segmentation and tagmosis are reviewed for Chelicerata. Depending on the outgroup, che- Received 4 April 2016 licerate origins are either among taxa with an anterior tagma of six somites, or taxa in which the ap- Accepted 18 May 2016 pendages of somite I became increasingly raptorial. All Chelicerata have appendage I as a chelate or Available online 21 June 2016 clasp-knife chelicera. The basic trend has obviously been to consolidate food-gathering and walking limbs as a prosoma and respiratory appendages on the opisthosoma. However, the boundary of the Keywords: prosoma is debatable in that some taxa have functionally incorporated somite VII and/or its appendages Arthropoda into the prosoma. Euchelicerata can be defined on having plate-like opisthosomal appendages, further Chelicerata fi Tagmosis modi ed within Arachnida. Total somite counts for Chelicerata range from a maximum of nineteen in Prosoma groups like Scorpiones and the extinct Eurypterida down to seven in modern Pycnogonida. Mites may Opisthosoma also show reduced somite counts, but reconstructing segmentation in these animals remains chal- lenging. Several innovations relating to tagmosis or the appendages borne on particular somites are summarised here as putative apomorphies of individual higher taxa. -

Geological History and Phylogeny of Chelicerata

Arthropod Structure & Development 39 (2010) 124–142 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Arthropod Structure & Development journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/asd Review Article Geological history and phylogeny of Chelicerata Jason A. Dunlop* Museum fu¨r Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Research on Evolution and Biodiversity at the Humboldt University Berlin, Invalidenstraße 43, D-10115 Berlin, Germany article info abstract Article history: Chelicerata probably appeared during the Cambrian period. Their precise origins remain unclear, but may Received 1 December 2009 lie among the so-called great appendage arthropods. By the late Cambrian there is evidence for both Accepted 13 January 2010 Pycnogonida and Euchelicerata. Relationships between the principal euchelicerate lineages are unre- solved, but Xiphosura, Eurypterida and Chasmataspidida (the last two extinct), are all known as body Keywords: fossils from the Ordovician. The fourth group, Arachnida, was found monophyletic in most recent studies. Arachnida Arachnids are known unequivocally from the Silurian (a putative Ordovician mite remains controversial), Fossil record and the balance of evidence favours a common, terrestrial ancestor. Recent work recognises four prin- Phylogeny Evolutionary tree cipal arachnid clades: Stethostomata, Haplocnemata, Acaromorpha and Pantetrapulmonata, of which the pantetrapulmonates (spiders and their relatives) are probably the most robust grouping. Stethostomata includes Scorpiones (Silurian–Recent) and Opiliones (Devonian–Recent), while -

An Illustrated Key to the Malacostraca (Crustacea) of the Northern Arabian Sea. Part VI: Decapoda Anomura

An illustrated key to the Malacostraca (Crustacea) of the northern Arabian Sea. Part 6: Decapoda anomura Item Type article Authors Kazmi, Q.B.; Siddiqui, F.A. Download date 04/10/2021 12:44:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/34318 Pakistan Journal of Marine Sciences, Vol. 15(1), 11-79, 2006. AN ILLUSTRATED KEY TO THE MALACOSTRACA (CRUSTACEA) OF THE NORTHERN ARABIAN SEA PART VI: DECAPODA ANOMURA Quddusi B. Kazmi and Feroz A. Siddiqui Marine Reference Collection and Resource Centre, University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan. E-mails: [email protected] (QBK); safianadeem200 [email protected] .in (FAS). ABSTRACT: The key deals with the Decapoda, Anomura of the northern Arabian Sea, belonging to 3 superfamilies, 10 families, 32 genera and 104 species. With few exceptions, each species is accompanied by illustrations of taxonomic importance; its first reporter is referenced, supplemented by a subsequent record from the area. Necessary schematic diagrams explaining terminologies are also included. KEY WORDS: Malacostraca, Decapoda, Anomura, Arabian Sea - key. INTRODUCTION The Infraorder Anomura is well represented in Northern Arabian Sea (Paldstan) (see Tirmizi and Kazmi, 1993). Some important investigations and documentations on the diversity of anomurans belonging to families Hippidae, Albuneidae, Lithodidae, Coenobitidae, Paguridae, Parapaguridae, Diogenidae, Porcellanidae, Chirostylidae and Galatheidae are as follows: Alcock, 1905; Henderson, 1893; Miyake, 1953, 1978; Tirmizi, 1964, 1966; Lewinsohn, 1969; Mustaquim, 1972; Haig, 1966, 1974; Tirmizi and Siddiqui, 1981, 1982; Tirmizi, et al., 1982, 1989; Hogarth, 1988; Tirmizi and Javed, 1993; and Siddiqui and Kazmi, 2003, however these informations are scattered and fragmentary. In 1983 McLaughlin suppressed the old superfamily Coenobitoidea and combined it with the superfamily Paguroidea and placed all hermit crab families under the superfamily Paguroidea. -

The Brain of the Remipedia (Crustacea) and an Alternative Hypothesis on Their Phylogenetic Relationships

The brain of the Remipedia (Crustacea) and an alternative hypothesis on their phylogenetic relationships Martin Fanenbruck*†, Steffen Harzsch†‡§, and Johann Wolfgang Wa¨ gele* *Fakulta¨t Biologie, Ruhr-Universita¨t Bochum, Lehrstuhl fu¨r Spezielle Zoologie, 44780 Bochum, Germany; and ‡Sektion Biosystematische Dokumentation and Abteilung Neurobiologie, Universita¨t Ulm, D-89081 Ulm, Germany Edited by May R. Berenbaum, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL, and approved December 16, 2003 (received for review September 26, 2003) Remipedia are rare and ancient mandibulate arthropods inhabiting ical study and reconstruction of the brain anatomy of Godzil- almost inaccessible submerged cave systems. Their phylogenetic liognomus frondosus Yager, 1989, (Remipedia, Godzilliidae) position is still enigmatic and the subject of extremely controver- from the Grand Bahama Island (12) followed by a discussion of sial debates. To contribute arguments to this discussion, we ana- ecological and phylogenetic implications. lyzed the brain of Godzilliognomus frondosus Yager, 1989 (Remi- pedia, Godzilliidae) and provide a detailed 3D reconstruction of its Methods anatomy. This reconstruction yielded the surprising finding that in The cephalothorax of a formalin-fixed Godzilliognomus frondo- comparison with the brain of other crustaceans such as represen- sus Yager, 1989, (Remipedia, Godzilliidae) specimen was em- tatives of the Branchiopoda and Maxillopoda the brain of G. bedded in Unicryl (British Biocell International, Cardiff, U.K.). frondosus is highly organized and well differentiated. It is matched Slices of 2.5 m were sectioned by using a Reichert-Jung in complexity only by the brain of ‘‘higher’’ crustaceans (Malacos- 2050-supercut. After toluidine-blue staining, digital images were traca) and Hexapoda. -

Bug Backgrounder

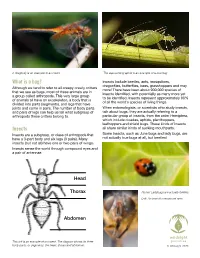

A dragonfly is an example of an insect The sap-sucking aphid is an example of a true bug What is a bug? Insects include beetles, ants, mosquitoes, dragonflies, butterflies, bees, grasshoppers and may Although we tend to refer to all creepy crawly critters more! There have been about 900,000 species of that we see as bugs, most of these animals are in insects identified, with potentially as many more yet a group called arthropods. This very large group to be identified. Insects represent approximately 80% of animals all have an exoskeleton, a body that is of all the world’s species of living things. divided into parts (segments), and legs that have joints and come in pairs. The number of body parts When entomologists, or scientists who study insects, and pairs of legs can help us tell what subgroup of talk about bugs, they are actually referring to a arthropods these critters belong to. particular group of insects, from the order Hemiptera, which include cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers and shield bugs. These kinds of insects Insects all share similar kinds of sucking mouthparts. Insects are a subgroup, or class of arthropods that Some insects, such as June bugs and lady bugs, are have a 3-part body and six legs (3 pairs). Many not actually true bugs at all, but beetles! insects (but not all) have one or two pairs of wings. Insects sense the world through compound eyes and a pair of antennae. Head Thorax Above: Ladybugs are actually beetles Left: An insect’s compound eyes Abdomen This ant is an example of an insect. -

Common Spiders (Arachnida: Araneae) in the Wichita Mountains and Surrounding Areas

Common Spiders (Arachnida: Araneae) in the Wichita Mountains and Surrounding Areas Angel A. Chiri Entomologist and abdomen) and does not include legs. Introduction Although this guide is primarily for spiders, harvestmen, scorpions, ticks, and sun spiders are Spiders belong in the Phylum Arthropoda, Class briefly mentioned. Arachnida, Order Araneae. These common arachnids are found in grasslands, forests, orchards, cultivated fields, backyards, gardens, empty lots, parks, and homes. There are some 570 genera and 3,700 species of spiders in North America, north of Mexico. According to an Oklahoma State University checklist at least some 187 genera and 432 species were recorded in the state. Cokendolpher and Bryce (1980) examined arachnid specimens collected at the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge by various groups between 1926 and 1978. Their work yielded a total of 182 arachnid species, of which 170 were spiders. Figure 1. Texas brown tarantula, Aphonopelma hentzi, male Many spiders are common and distinctive, often seen resting on their webs or crawling on the Summary of Structure and Function ground during the warmer months. The larger orb-weavers, for instance, are readily noticed in Being arthropods, spiders have a rigid external late summer and early fall because of their size skeleton, or exoskeleton, and jointed legs. The and conspicuousness. Others are uncommon or spider body consists of two segments, the seldom seen because of their secretive habits or cephalothorax (anterior segment) and the small size. For instance, some spiders that live abdomen (posterior segment), joined by a short, in leaf litter are minute, cryptic, and seldom thin, flexible pedicel. The dorsal part of the noticed without the use of special collecting cephalothorax is the carapace. -

26. Arthropods

Meet CSU Extension Agronomy Entomology Agent Connecting Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math concepts to our everyday lives. Bob Hammon Age Appropriate: http://wci.colostate.edu/ Picture Perfect Arachnids! 4th—HS grades Bob Hammon is Tri River Spiders, Scorpions Area Extension agent with re- Spiders, Scorpions Time Required: sponsibilities in entomology Ticks, and Mites At least 1 hour and agronomy. He just cele- http://www.nps.gov/features/yell/slidefile/arthropods/spiders/Images/06644.jpg Materials: brated 25 years with Colorado This is the time of year when we begin to see elaborate webs and the associated Patience! State University (CSU), the orb spiders and other spiders invading our homes. We are going to take a closer Camera first 15 years with the Western look—literally—at spiders, their anatomy, their amazing ability to build webs, and Computer Colorado research Center at how to classify them by photographing and then identifying them. Optional: printer Fruita, and the last 10 with Spiders are the 7th most diverse group of animals (insects being #1), with more TRA Extension at the Mesa than 43,600 species described in 109 families! Spiderlike fossils have been found in The Set-up: County. He has a B.S. in Natu- rocks that are 386 million years old, but the first true spiders (with spinnerets) don’t Collect the equipment. If ral Resources from the Univer- show up for another 75 million years. Before we begin, let’s look closer at the you do not have a camera, your local 4-H agent can sity of Michigan and a M.S. -

Lecture Notes

ENT 760 Lecture 1 - Definitions; Evolution Ins. Morph. EVOLUTION We will begin this semester with a discussion of the evolution leading to the Arthropoda, and then the phylogenetic relationships within the Arthropoda itself. There has been a tremendous change in our thoughts about these relationships in recent years, due primarily to the use of DNA data, and then a re-interpretation of the morphological data. Traditionally, we considered the Arthropoda to be most closely related to the Annelida. In fact, we either thought the Arthropoda descended from the Annelids, or that both the Annelida and the Arthropoda descended from a common ancestor. In your handouts, you will see the proposed hypothesis of how the insects may have evolved from an annelid like ancestor. Also, we have usually indicated that the Onychophora were probably related (perhaps an intermediate between the Annelida and the Arthropoda). There may still be some truth to this process, but the ancestor may be different. Recent work, especially molecular studies (see handout - Mallatt, 2004 paper), have called into question the above scenario. It has now been proposed that the Arthropoda should be grouped together with the Nematoda and a few other small phyla into a group called the Ecdysozoa. Not only are the ribosomal DNA sequences similar, but all of these animals have in common a cuticle that is periodically molted. The Annelida have now been placed in a group called the Lophotrochozoa along with Molluscs, Platyhelminthes, and the Rotifera. This is supported by other recent studies from different sources. There is no current agreement on where the Onychophora belong, except that it probably does not belong with the Arthropoda (it appears that it is still related to the basal stem of the Arthropoda). -

Phylum Arthropoda Phylum Arthropoda

Phylum Arthropoda Phylum Arthropoda • “jointed foot” • Largest phylum • 900,000 species – 75% of all known species • Insects, spiders, crustaceans, millipedes, scorpions, ticks, etc. 2 Phylum Arthropoda • Most successful phylum – Ecologically diverse – Present in all regions of the earth • Adapted to air, land, freshwater, marine, other organisms 3 The relative number of species contributed to the total by each phylum of animals. 97% invertebrates. Lots of Arthropods! (Molluscs second) Reasons for success 1. Versatile exoskeleton 2. Efficient locomotion 3. Air piped directly to cells (terrestrial) 4. Highly developed sensory organs 5. Complex behavior 6. Metamorphosis 5 Molecular evidence places insects WITHIN the Crustacea Characteristics of the Arthropoda • Bilaterally symmetrical • Protostome, coelomate (reduced) • Segmented (metameric) • Body divided into head, thorax and abdomen; cephalothorax and abdomen; or fused head and trunk. Rove beetle Goliath bird-eating spider Exoskeleton • Exoskeleton of cuticle. • Exoskeleton secreted by underlying epidermis. Made of chitin, protein, waxes, and often calcium carbonate. • Exoskeleton is shed periodically (ecdysis) as the organism grows. • Provides strength and protection Jointed Legs • Jointed appendages. Primitively one pair per segment, but number often reduced. • Appendages often greatly modified for specialized tasks. Segmented, jointed appendages Appendages adapted for special tasks Cephalothorax Abdomen Antennae (sensory Thorax reception) Head Swimming appendages (one pair located under each abdominal segment) Walking legs Pincer (defense) Mouthparts (feeding) Arthropod Skeleton and Compound Eye 15 Compound Eye • Composed of many similar, closely-packed facets (called ommatidia ) which are the structural and functional units of vision. • Very sensitive to movement. • Wide light spectrum - UV Muscular System • Muscular system is complex and muscles attach to the exoskeleton. -

Malacostracan Phylogeny and Evolution

ERIK DAHL Department of Zoology, Lund, Sweden MALACOSTRACAN PHYLOGENY AND EVOLUTION ABSTRACT Malacostracan ancestors were benthic-epibenthic. Evolution of ambulatory stenopodia prob- ably preceded specialization of natatory pleopods. This division of labor was the prere- quisite for the evolution of trunk tagmosis. It is concluded that the ancestral malacostracan was probably more of a pre-eumalacostracan than a phyllocarid type, and that the phyllo- carids constitute an early branch adapted for benthic life. The same is the case with the hoplocarids, here regarded as a separate subclass with eumalacostracan rather than phyllo- carid affinities, although that question remains open. The systematic concept Eumalaco- straca is here reserved for the subclass comprising the three caridoid superorders, Syncarida, Eucarida and Peracarida. The central caridoid apomorphy, proving the unity of caridoids, is the jumping escape reflex system, manifested in various aspects of caridoid morphology. The morphological evidence indicates that the Syncarida are close to a caridoid stem-group, and that the Eumalacostraca sensu stricto were derived from pre-syncarid ancestors. Ad- vanced hemipelagic-pelagic caridoids probably evolved independently within the Eucarida and Peracarida. 1 INTRODUCTION The differentiation of the major crustacean taxa must have taken place very early, pro- bably at least partly in the Precambrian (cf. Bergstrom 1980). Fronrthe Cambrian we have proof of the presence of branchiopods (Simonetta & Delle Cave 1980, Briggs 1976), ostra- -

Meet the Invertebrates Puppet Show! Location: Indoors/Outdoors

Meet the Invertebrates Puppet Show! Location: Indoors/outdoors Essential Question: Objectives: Learners will: 1) Identify 5 non-insect What are the different types of invertebrates? invertebrates likely to be seen around the Background Information: classroom site. Most of the invertebrates described in this activity are, like insects, 2) State at least one fact in the phylum Arthropoda. Arthropoda have jointed appendages about the following invertebrates: spiders, and a hard exoskeleton. mites and ticks, scorpions, daddy One important group of arthropods are the Class Arachnida. longlegs, millipedes Arachnids have eight legs and lack wings and antennae. Unlike and centipedes, insects, most have only two distinct body parts – the cephalothorax earthworms, roly- polies (pill bugs), (both head and thorax) and an abdomen. They have a pair of jaw- snails and slugs. like or fang-bearing appendages called chelicerae in front of the mouth. These are comparable to insect jaws or mandibles. They Skills: communication, have a pair of leg-like appendages – called pedipalps – between the observation, listening, chelicerae and the first pair of legs. Most arachnids are predators. analysis Supplies: Spiders are arachnids in the Order Araneae. Their cephalothorax 20 insect and other and abdomen are distinctly separated by a „waist‟. The top of the invertebrate GEN Eco- cephalothorax is protected by a shield-like covering. Most – but service ID cards not all – spiders have eight simple eyes. Below them, the Spider, orb weaver chelicerae end in fangs. Venom is produced in glands and empties Earthworm Spider, jumping into the fangs. Spiders, generally, crush their victims by rubbing Land Snail the chelicerae against each other and against the bases of the Centipede pedipalps, and then suck out their juices.