2008 Sept-Oct

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 89 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #557 - Tasha Tudor Original Art from Wind in the Willows #190 - Gordon Craig Association Copy with Letter #383 - John R. Neill Art from Tik-Tok of Oz #423 - Original Art from The Little Engine That Could #54 - Man Ray ABC - Signed Limited Edition Pg 3 Helen & Marc Younger [email protected] MET LIFE HEALTH ABC COMPLETE WITH INSERT 1. ABC. (ADVERTISING) IN STYLE OF JANET LAURA SCOTT / ABC. NY: Metropolitan Life Ins. CLOTH ABC Co. ca 1920. 8vo, (5 1/4 x 7 3/4”) pictorial wraps, light soil, VG. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii PREFACE xiii SYNOPSIS xvii GLOSSARY xix A WORD ABOUT SYNTAX IN THIS VOLUME xxiii ABBREVIATIONS xxv BIBLIOGRAPHIA BAUMIANA 1 BOOKS OF NON-FICTION AND FANTASY 3 The Book of the Hamburgs 3 Mother Goose in Prose 5 By the Candelabra’s Glare 13 Father Goose: His Book 19 The Songs of Father Goose 27 The Army Alphabet 31 The Navy Alphabet 33 A New Wonderland 35 The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors 38 American Fairy Tales 45 Dot and Tot of Merryland 48 The Master Key 54 The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus 59 The Enchanted Island of Yew 67 The Magical Monarch of Mo 73 The Woggle-Bug Book 82 Queen Zixi of Ix 85 John Dough and the Cherub 90 Father Goose’s Year Book 96 Baum’s American Fairy Tales 98 L. Frank Baum’s Juvenile Speaker 101 The Daring Twins 103 The Sea Fairies 107 Phoebe Daring 113 Sky Island 116 Baum’s Own Book for Children 121 The Snuggle Tales and The Oz-Man Tales 124 Little Bun Rabbit 125 Once Upon a Time 128 The Yellow Hen 131 The Magic Cloak 134 Jack Pumpkinhead 137 The Gingerbread Man 139 x BIBLIOGRAPHIA PSEUDONYMIANA 141 PSEUDONYMOUS BOOKS OF FICTION AND FANTASY 143 SCHUYLER STAUNTON 147 The Fate of a Crown 147 Daughters of Destiny 154 LAURA BANCROFT 158 The Twinkle Tales Series 158 Mr. Woodchuck 158 Bandit Jim Crow 162 Prairie-Dog Town 165 Prince Mud-Turtle 169 Sugar-Loaf Mountain 173 Twinkle’s Enchantment 176 The Twinkle Tales – Continued 179 Policeman Bluejay 179 Babes in Birdland 181 Twinkle and Chubbins 185 SUZANNE METCALF 188 Annabel 188 EDITH VAN DYNE 193 The Aunt Jane’s Nieces Series 193 Binding and Dust Jacket Formats 193 Aunt Jane’s Nieces 200 Aunt Jane’s Nieces Abroad 209 Aunt Jane’s Nieces at Millville 217 Aunt Jane’s Nieces at Work 224 Aunt Jane’s Nieces in Society 230 Aunt Jane’s Nieces and Uncle John 236 Aunt Jane’s Nieces on Vacation 241 Aunt Jane’s Nieces on the Ranch 246 Aunt Jane’s Nieces Out West 250 Aunt Jane’s Nieces in the Red Cross 254 The Flying Girl Series 258 The Flying Girl 258 The Flying Girl and Her Chum 262 The Bluebird Books, a.k.a. -

A Research Guide for L. Frank Baum

The Wizard Behind Oz and Other Stories: A Research Guide for L. Frank Baum By: Karla Lyles October 2006 2 Introduction: In 1900 Lyman Frank Baum published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a phenomenal literary success that inspired posthumous writings to continue the Oz series into more than 40 books (including the originals). Although Baum published several additional series of books (most pseudonymously written) and other individual writings, he is best known for The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. A considerable number of books, articles, dissertations, and electronic resources containing information about the Oz masterpiece are available, supplying a wealth of information for the curious Baum fan or avid Baum researcher. To locate information about Baum and his writings I consulted several search engines, including ABELL, British Library Catalogue, Copac, DLB, MLAIB, Wilson, and WorldCat, as well as referred to footnotes in printed materials I obtained. I have provided references to the databases I located each of the materials in within the brackets at the end of the citation entries, allowing the reader to consult those databases if he/she so chooses to pursue further research. For those individuals who may be unfamiliar with the acronyms of some of the databases, ABELL is the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature, DLB is the Dictionary of Literary Biography, and MLAIB is the MLA International Bibliography. I also relied substantially on the services of Interlibrary Loan to secure materials that are not available in Evans Library at Texas A & M University, and I recommend the use of Interlibrary Loan in conducting research to allow for the acquisition of materials that would otherwise remain unobtainable. -

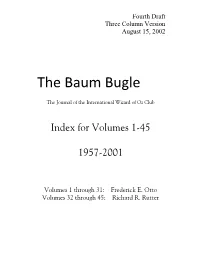

The Baum Bugle

Fourth Draft Three Column Version August 15, 2002 The Baum Bugle The Journal of the International Wizard of Oz Club Index for Volumes 1-45 1957-2001 Volumes 1 through 31: Frederick E. Otto Volumes 32 through 45: Richard R. Rutter Dedications The Baum Bugle’s editors for giving Oz fans insights into the wonderful world of Oz. Fred E. Otto [1927-95] for launching the indexing project. Peter E. Hanff for his assistance and encouragement during the creation of this third edition of The Baum Bugle Index (1957-2001). Fred M. Meyer, my mentor during more than a quarter century in Oz. Introduction Founded in 1957 by Justin G. Schiller, The International Wizard of Oz Club brings together thousands of diverse individuals interested in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and this classic’s author, L. Frank Baum. The forty-four volumes of The Baum Bugle to-date play an important rôle for the club and its members. Despite the general excellence of the journal, the lack of annual or cumulative indices, was soon recognized as a hindrance by those pursuing research related to The Wizard of Oz. The late Fred E. Otto (1925-1994) accepted the challenge of creating a Bugle index proposed by Jerry Tobias. With the assistance of Patrick Maund, Peter E. Hanff, and Karin Eads, Fred completed a first edition which included volumes 1 through 28 (1957-1984). A much improved second edition, embracing all issues through 1988, was published by Fred Otto with the assistance of Douglas G. Greene, Patrick Maund, Gregory McKean, and Peter E. -

DAMMIT, TOTO, WE're STILL in KANSAS: the FALLACY of FEMINIST EVOLUTION in a MODERN AMERICAN FAIRY TALE by Beth Boswell a Diss

DAMMIT, TOTO, WE’RE STILL IN KANSAS: THE FALLACY OF FEMINIST EVOLUTION IN A MODERN AMERICAN FAIRY TALE by Beth Boswell A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University May 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Martha Hixon, Director Dr. Will Brantley Dr. Jane Marcellus This dissertation is dedicated, in loving memory, to two dearly departed souls: to Dr. David L. Lavery, the first director of this project and a constant voice of encouragement in my studies, whose absence will never be wholly realized because of the thousands of lives he touched with his spirit, enthusiasm, and scholarship. I am eternally grateful for our time together. And to my beautiful grandmother, Fay M. Rhodes, who first introduced me to the yellow brick road and took me on her back to a pear-tree Emerald City one hundred times or more. I miss you more than Dorothy missed Kansas. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the educators who have pushed me to challenge myself, to question everything in the world around me, and to be unashamed to explore what I “thought” I already knew, over and over again. Though there are too many to list by name, know that I am forever grateful for your encouragement and dedication to learning, whether in the classroom or the world. I would like to thank my phenomenal committee for their tireless support and assistance in this project. I am especially grateful for Dr. Martha Hixon, who stepped in as my director after the passing of Dr. -

Book List: Complete List of Books by Alisa Avruch and Sharon Schwartz

A_00663 Secular Book List: Complete List of Books By Alisa Avruch and Sharon Schwartz Grade Level: Elementary, Middle School, High School, Administration Description: Updated summer 2015! The Secular Book List contains almost 4000 secular children’s books which have been evaluated for appropriateness of content. This list is designed to enable parents and educators to choose secular reading material which is suitable to be read by Jewish children. An explanation for the criteria used for evaluation is included. The Secular Book List is available in four formats: 1. Secular Book List: Complete List of Books (A_00663). CURRENT FILE. This item contains the entire list of evaluated books, including those books which were not approved. Detailed comments on each book are provided to help adults discern the appropriateness of content. Download this item for all books which have been reviewed by this contributor. 2. Secular Book List: Approved and Questionable Books(A_00663-05). This item contains only those books whose content was deemed acceptable or questionable and includes comments explaining why the books were rated as such. It does not include books which have not been approved. Download this item if you would like to select books from a list which does not contain books which were deemed inappropriate. 3. Secular Book List: Approved Books Only (A_00663-03). This item contains only those books from the Secular Book List which were deemed appropriate. This file does not include comments as it is intended for student use. 4. Secular Book List: New Books Reviewed in 2015 (A_00663-06). This item contains all books (approved, questionable and unapproved) which were reviewed in the year 2015. -

2008 Nov-Dec

November-DecemberThe 2008 horatioNEWSBOY Alger Society Page 1 OFFICIAL PUBLICATION A magazine devoted to the study of Horatio Alger, Jr., his life, works, and influence on the culture of America. VOLUME XLVI NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2008 NUMBER 6 Beckoning at the Gate: Horatio Alger, Jr. and the Literary Canon -- See Page 5 H.A.S. convention in Charlottesville: A first glance -- See Page 3 The Emmet Street Holiday Inn, Charlottesville, Va. Odd One Out Annabel; or, Suzanne Metcalf’s -- Conclusion, Page 13 unexpected homage to Horatio Alger Page 2 NEWSBOY November-December 2008 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 HORATIO ALGER SOCIETY 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 To further the philosophy of Horatio Alger, Jr. and to encourage the 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 spirit of Strive and Succeed that for half a century guided Alger’s 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 -

Children's Books & Illustrated

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 88 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #281 - Michael Hague Original Art of Gnomes and Fairies #332 - 1st ed. signed by L’Engle #276 - Hader dummy for Here Bingo #154 - Chris Conover Original Art for Mother Goose Pg Helen & Marc Younger [email protected] STEAM LAUNDRY ABC - LOUIS WAIN COVER FRENCH HAND-COLORED ABC PANORAMA 1. ABC. (ADVERTISING) NURSERY RHYMES FOR THE LITTLE ONES. 4. ABC. (BIRDS) ALPHABET DES OISEAUX. France, ca 1860. 8vo, orange Croydon (UK): American Steam cloth, pictorial paste-on, expertly rebacked, Fine.