1982 Slive-On-Ruisdael.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lectionary Texts for June 20, 2021 • Fourth Sunday After Pentecost

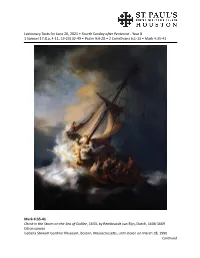

Lectionary Texts for June 20, 2021 •Fourth Sunday after Pentecost- Year B 1 Samuel 17:(1a, 4-11, 19-23) 32-49 • Psalm 9:9-20 • 2 Corinthians 6:1-13 • Mark 4:35-41 Mark 4:35-41 Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633, by Rembrandt van Rijn, Dutch, 1606-1669 Oil on canvas Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts, until stolen on March 18, 1990 Continued Lectionary Texts for the Fourth Sunday after Pentecost• June 20, 2021 • Page 2 In his only painted seascape, Rembrandt dramatically portrays the continuing battle of nature against human frailty, both physical and spiritual. The frightened and overwhelmed disciples struggle to retain control of their fishing boat as huge waves crash over the bow. One disciple is hanging over the side of the boat vomiting. A sail is torn, rope lines are flying loose, disaster is imminent as rocks appear in the left foreground. The dark clouds, the wind, the waves combine to create the terror of the painting and the terror of the disciples. Nature’s upheaval is the cause of, as well as a metaphor for, the fear that grips the disciples. The emotional turbulence is magni- fied by the dramatic impact of the painting, approximately 4’ wide by 5’ high. Jesus, whose face is lightened in the group on the right, remains calm. He woke up and rebuked the wind, and said to the sea, “Peace! Be still!” Then the wind ceased, and there was a dead calm, and he asked the disciples, “Why are you afraid? Have you still no faith?” The face of a 13th disciple looks directly out at the viewer in the horizontal center of the painting. -

Ständige Sammlung Des Mauritshuis

Mauritshuis Factsheet 2020 The Mauritshuis is home to the best of Dutch paintings from the Golden Age. The compact, world-renowned collection, is situated in the heart of The Hague. Masterpieces such as Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp by Rembrandt, The Goldfinch by Fabritius and The Bull by Potter are on permanent display in the intimate museum rooms of the seventeenth-century monument. A visit to the Mauritshuis lasts approximately 1-1.5 hours. Group reservations can be made via mauritshuis.nl/en/guidedtours Address Opening hours Mauritshuis Monday 1 pm – 6 pm Plein 29 Tuesday through Sunday 10 am – 6 pm 2511 CS The Hague Thursday 10 am – 8 pm Mauritshuis.nl *The Mauritshuis is closed on 25 December and 1 January There are free parking spaces for buses in the vicinity of the Mauritshuis. For up-to-date information please visit mauritshuis.nl/en/touroperators Admission (subject to change) € 13.50* Tour operators free Under the age of 19 *The usual entrance fee is € 15,50. Entrance tickets are valid for the permanent exhibition, as well as any special exhibitions that may be taking place at the Mauritshuis. The Mauritshuis offers the option of a voucher contract, please contact us for more information. Multimedia Tour A multimedia tour of the collection is included in the ticket price. You can either download the tour as an app onto your own device or hire a device at the museum, based on availability. If you wish to hire a device, please make a reservation in advance. -

The Charms of Holland

SMALL GROUP Ma xi mum of LAND 24 Travele rs JO URNEY The Charms of Holland Inspiring Moments > Stroll through quaint North-Holland towns, from Hoorn with its 17th-century harbor to Bergen, a tranquil artists’ haven. > Wander in inviting, compact Haarlem amid quiet waterways and vibrant culture. INCLUDED FEATURES > Taste tempting, classic specialties: Accommodations (with baggage handling) Itinerary fresh-caught seafood, Gouda cheese and – 7 nights in Haarlem, Netherlands, at the Day 1 Depart gateway city poffertjes , sugar-dusted mini-pancakes. first-class Amrath Grand Hotel Frans Hals. Day 2 Arrive in Amsterdam and > Cruise on Amsterdam’s pretty canals transfer to hotel in Haarlem and strike off to explore on your own. Extensive Meal Program – 7 breakfasts, 3 lunches and 3 dinners, Day 3 Gouda | Rotterdam > Delve into politics and art in The Hague, including Welcome and Farewell Dinners; Day 4 Haarlem | Hoorn | Afsluitdijk the government seat and home of the tea or coffee with all meals, plus wine Day 5 Amsterdam | Zandvoort acclaimed Mauritshuis museum. with dinner. Day 6 Hoge Veluwe National Park > View extraordinary pieces by van Gogh and other artists at the Kröller-Müller Your One-of-a-Kind Journey Day 7 Aalsmeer | The Hague Museum, set in a beautiful national park. – Discovery excursions highlight the local Day 8 Haarlem culture, heritage and history. > Admire the innovative modern architecture Day 9 Transfer to Amsterdam airport of Rotterdam, Europe’s largest port city. – Expert-led Enrichment programs and depart for gateway city enhance your insight into the region. > Be wowed by the kaleidoscopic colors and lightning pace of the world’s largest – AHI Sustainability Promise: Flights and transfers included for AHI FlexAir participants. -

Sotheby's Old Master & British Paintings Evening Sale London | 08 Jul 2015, 07:00 PM | L15033

Sotheby's Old Master & British Paintings Evening Sale London | 08 Jul 2015, 07:00 PM | L15033 LOT 14 THE PROPERTY OF A LADY JACOB ISAACKSZ. VAN RUISDAEL HAARLEM 1628/9 - 1682 AMSTERDAM HILLY WOODED LANDSCAPE WITH A FALCONER AND A HORSEMAN signed in monogram lower right: JvR oil on canvas 101 by 127.5 cm.; 39 3/4 by 50 1/4 in. ESTIMATE 500,000-700,000 GBP PROVENANCE Lady Elisabeth Pringle, London, 1877; With Galerie Charles Sedelmeyer, Paris, 1898; Mrs. P. C. Handford, Chicago; Her sale, New York, American Art Association, 30 January 1902, lot 59; William B. Leeds, New York; His sale, London, Sotheby’s, 30 June 1965, lot 25; L. Greenwell; Anonymous sale ('The Property of a Private Collector'), New York, Sotheby’s, 7 June 1984, lot 76, for $517,000; Gerald and Linda Guterman, New York; Their sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 14 January 1988, lot 32; Anonymous sale New York, Sotheby’s, 2 June 1989, lot 16, for $297,000; With Verner Amell, London 1991; Acquired from the above by Hans P. Wertitsch, Vienna; Thence by family descent. EXHIBITED London, Royal Academy, Winter Exhibition, 1877, no. 25; New York, Minkskoff Cultural Centre, The Golden Ambience: Dutch Landscape Painting in the 17th Century, 1985, no. 10; Hamburg, Kunsthalle, Jacob van Ruisdael – Die Revolution der Landschaft, 18 January – 1 April 2002, and Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, 27 April – 29 July 2002, no. 31; Vienna, Akademie der Bildenden Künste, on loan since 2010. LITERATURE C. Sedelmeyer, Catalogue of 300 paintings, Paris 1898, pp. 1967–68, no. 175, reproduced; C. -

DUTCH and ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850

DUTCH AND ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850 The art and ship models in this station are devoted to the early Dutch and English seascape painters. The historical emphasis here explains the importance of the sea to these nations. Historical Overview: The Dutch: During the 17th century, the Netherlands emerged as one of the great maritime oriented empires. The Dutch Republic was born in 1579 with the signing of the Union of Utrecht by the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands. Two years later the United Provinces of the Netherlands declared their independence from the Spain. They formed a loose confederation as a representative body that met in The Hague where they decided on issues of taxation and defense. During their heyday, the Dutch enjoyed a worldwide empire, dominated international trade and built the strongest economy in Europe on the foundation of a powerful merchant class and a republican form of government. The Dutch economy was based on a mutually supportive industry of agriculture, fishing and international cargo trading. At their command was a huge navy and merchant fleet of fluyts, cargo ships specially designed to sail through the world, which controlled a large percentage of the international trade. In 1595 the first Dutch ships sailed for the East Indies. The Dutch East Indies Company (the VOC as it was known) was established in 1602 and competed directly with Spain and Portugal for the spices of the Far East and the Indian subcontinent. The success of the VOC encouraged the Dutch to expand to the Americas where they established colonies in Brazil, Curacao and the Virgin Islands. -

National Gallery of Art April 23, 1982 - October 31, 1982

Note to Editors; The revised dates and itinerary for the exhibition Mauritshuis; Dutch Painting of the Golden Age from the Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, are as follows: National Gallery of Art April 23, 1982 - October 31, 1982 Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas November 20, 1982 - January 30, 1983 The Art Institute of Chicago February 26, 1983 - May 29, 1983 Los Angeles County Museum of Art June 30, 1983 - September 11, 1983 \ i: w s 111; i, i« \ s i; STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 7374215 FOURTH extension 51: ADVANCE FACT SHEET Exhibition: Mauritshuis: Dutch Painting of the Golden Age from the Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague Dates: April 23, 1982 - September 6, 1982 Description: Forty outstanding examples of 17th-century Dutch painting from the Mauritshuis, the Royal Picture Gallery of The Netherlands, will begin a national tour which coincides with the bicentennial anniversary of Dutch-American diplomatic relations. Johannes Vermeer's Head of a Young Girl, Carl Fabritius' Goldfinch, Frans Hals' Laughing Boy and three masterworks by Rembrandt will be on view, as will paintings by Jan Steen, Jan van Goyen, Jacob van Ruisdael, Gerard ter Borch and other masters from this unsurpassed period of Dutch art. Itinerary: After opening at the National Gallery, the exhibition will travel to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (October 6, 1982 - January 30, 1983); the Art Institute of Chicago (February 26, 1983 - May 29, 1983); and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (June 30, 1983 - September 11, 1983). Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., Curator, Dutch Painting, and Dodge Thompson, Executive Curator, National Gallery of Art, worked on organizing the exhibition for the American tour. -

Recent Acquisitions (2006–20) at the Mauritshuis, the Hague

Recent acquisitions (2006–20) at the Mauritshuis, The Hague Supplement COVER_NOV20.indd 1 09/11/2020 09:41 Recent acquisitions (2006–20) at the Mauritshuis, The Hague he royal picture gallery mauritshuis in The 1. Paintings by Nicolaes Berchem reunited at the Mauritshuis. Hague is often likened to a jewellery box that contains (Photograph Ivo Hoekstra). nothing but precious diamonds. Over the past fifteen BankGiro Lottery and the Rembrandt Association, as well as individual years the museum has continued to search for outstanding benefactors, notably Mr H.B. van der Ven, who has helped the museum time works that would further enhance its rich collection of and again. That the privatised Mauritshuis – an independent foundation Dutch and Flemish old master paintings. A director who since 1995 – benefits from private generosity is proved by a great many wants to make worthwhile additions to a collection of such quality must gifts, including seventeenth-century Dutch landscapes by Jacob van Geel Taim very high indeed. The acquisitions discussed here were made during (Fig.5) and Cornelis Vroom (Fig.4), as well as works from the eighteenth the directorship of Frits Duparc, who in January 2008 retired as Director century: a still life by Adriaen Coorte (Fig.2) and a portrait of a Dutch after seventeen years at the museum, and his successor, Emilie Gordenker, sitter by the French travelling artist Jean-Baptiste Perronneau (Fig.16). who earlier this year left the Mauritshuis for a position at the Van Gogh New acquisitions are also supported by numerous other foundations and Museum, Amsterdam. The present Director of the Mauritshuis, Martine funds, all mentioned in the credit lines of individual works. -

Pride of Place: Dutch Cityscapes in the Golden Age

Updated Wednesday, January 28, 2009 | 3:12:10 PM Last updated Wednesday, January 28, 2009 Updated Wednesday, January 28, 2009 | 3:12:10 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Pride of Place: Dutch Cityscapes in the Golden Age - Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required(*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Cat. No. 1 / File Name: 246-045.jpg Title Section Raw Cat. No. 1 / File Name: 246-045.jpg Jan Beerstraten Jan Beerstraten The Old Town Hall of Amsterdam on Fire in 1652, c. 1652-1655 The Old Town Hall of Amsterdam on Fire in 1652, c. 1652-1655 oil on panel; 89 x 121.8 cm (35 1/16 x 47 15/16 in.) oil on panel; 89 x 121.8 cm (35 1/16 x 47 15/16 in.) Amsterdams Historisch Museum Amsterdams Historisch Museum Cat. -

Print Format

Allaert van Everdingen (Alkmaar 1621 - Amsterdam 1675) Month of August (Virgo): The Harvest brush and grey and brown wash 11.1 x 12.8 cm (4⅜ x 5 in) The Month of August (Virgo): The Harvest has an extended and fascinating provenance. Sold as part of a complete set of the twelve months in 1694 to the famed Amsterdam writer and translator Sybrand I Feitama (1620-1701), it was passed down through the literary Feitama family who were avid collectors of seventeenth-century Dutch works on paper.¹ The present work was separated from the other months after their 1758 sale and most likely stayed in private collections until 1936 when it appeared in Christie’s London saleroom as part of the Henry Oppenheimer sale. Allaert van Everdingen was an exceptional draughtsman who was particularly skilled at making sets of drawings depicting, with appropriate images and activities, the twelve months of the year.² This tradition was rooted in medieval manuscript illumination, but became increasingly popular in the context of paintings, drawings and prints in the sixteenth century.³ In the seventeenth century, the popularity of such themed sets of images began to wane, and van Everdingen’s devotion to the concept was strikingly unusual. He seems to have made at least eleven sets of drawings of the months, not as one might have imagined, as designs for prints, but as artistic creations in their own right. Six of these sets remain intact, while Davies (see lit.) has reconstructed the others, on the basis of their stylistic and physical characteristics, and clues from the early provenance of the drawings. -

Forest Scene Or a Panoramic View of Haarlem

ebony frames, Isaack van Ruysdael was also a paint of Haarlem on 14 March 1682, but may well have er. Jacob van Ruisdael's earliest works, dated 1646, died in Amsterdam, where he is recorded in January were made when he was only seventeen or eighteen. of that year. He entered the Haarlem painters' guild in 1648. It is One of the greatest and most influential Dutch not known who his early teachers were, but he prob artists of the seventeenth century, Ruisdael was also ably learned painting from his father and his uncle the most versatile of landscapists, painting virtually Salomon van Ruysdael. Some of the dunescapes every type of landscape subject. His works are char that he produced during the late 1640s clearly draw acterized by a combination of almost scientific on works by Salomon, while his wooded landscapes observation with a monumental and even heroic of these years suggest he also had contact with the compositional vision, whether his subject is a dra Haarlem artist Cornelis Vroom (c. 1591 -1661). matic forest scene or a panoramic view of Haarlem. Houbraken writes that Ruisdael learned Latin at Early in his career he also worked as an etcher. the request of his father, and that he later studied Thirteen of his prints have survived, along with a medicine, becoming a famous surgeon in Amster considerable number of drawings. dam. Two documents are cited by later authors in In addition to Ruisdael's numerous followers, support of the latter claim, the first being a register most important of which were Meindert Hobbema of Amsterdam doctors that states that a "Jacobus and Jan van Kessel (1641 /1642-1680), the names of Ruijsdael" received a medical degree from the Uni several other artists are associated with him by virtue versity of Caen, in Normandy, on 15 October 1676. -

Rare Cityscape by Jacob Van Ruisdael of Budapest on Loan at the Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age Exhibition

Press release Amsterdam Museum 25 February 2015 Rare cityscape by Jacob van Ruisdael of Budapest on loan at the Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age exhibition For a period of one year commencing on the 27th of February, the Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age exhibition will be enriched with a rare cityscape by Jacob van Ruisdael (1628-1682) from the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum (Museum of Fine Arts) in Budapest: View of the Binnenamstel in Amsterdam. The canvas shows Amsterdam in approximately 1655, shortly before Amstelhof was built, the property in which the Hermitage Amsterdam is currently situated. The painting is now back in the city where it was created, for the first time since 1800. With this temporary addition, visitors to the Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age can experience how the city looked around 350 years ago seen from the place where they will end up after their visit. There are only a few known cityscapes by Jacob van Ruisdael. Usually, with this perhaps most "Dutch" landscape painter, the city would at best figure in the background, as in his views of Haarlem, Alkmaar, Egmond and Bentheim. Only in Amsterdam, where he is documented as being a resident from 1657, did he stray a few times within the city walls. It has only recently been established properly and precisely which spot in which year is depicted on the painting. Curator of paintings, sketches and prints Norbert Middelkoop from the Amsterdam Museum described it last year in an entry for the catalogue on the occasion of the Rembrandt and the Dutch Golden Age exhibition in the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum in Budapest. -

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn – the Storm on the Sea of Galilee

1 Classical Arts Universe - CAU Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn – The Storm on the Sea of Galilee Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, the Dutch painting marvel, always took interest in portraying landscapes, self-portraits and portraits of other artists. His landscape depictions have been never purely about the aesthetics of Nature, but predicted many things about hua life like strife, ager, hope, desire, et. The “tor o the “ea of Galilee or Christ i the Storm on the “ea of Galilee is suh a asterpiee depitig the Bilial see of Jesus and the disciples crossing the sea when there is a raging storm. The painting was completed in the year 1633 and Rembrandt took the maritime theme of the painting to ensure that the theme will be familiar to the people of the age and time. As an effort to establish himself as an artist, he took this subject and it is his only seascape painting. The Storm on the Sea of Galilee depicts the time when the disciples were terrified of the violent storm and are perplexed about their actions. A fierce wave is shown lifting the boat and it is about to engulf the boat into the sea. Christ looks at his disciples and their state of mind from the stern and is about to command the storm to halt. All the distressful renderings in the painting are consoled by a yellow light that is shown to set apart the clouds and create a hope to the members on the boat. The mast shown in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee appears in the form of a Cross, indicating that faith is still there for those who pray the God in times of storming human frailties – be it spiritual or physical.