Qvol. 11 No. 2 December (2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saint Rita of Cascia Catholic.Net

Saint Rita of Cascia Catholic.net Daughter of Antonio and Amata Lotti, a couple known as the Peacemakers of Jesus; they had Rita late in life. From her early youth, Rita visited the Augustinian nuns at Cascia, Italy, and showed interest in a religious life. However, when she was twelve, her parents betrothed her to Paolo Mancini, an ill-tempered, abusive individual who worked as town watchman, and who was dragged into the political disputes of the Guelphs and Ghibellines. Disappointed but obedient, Rita married him when she was 18, and was the mother of twin sons. She put up with Paolo’s abuses for eighteen years before he was ambushed and stabbed to death. Her sons swore vengeance on the killers of their father, but through the prayers and interventions of Rita, they forgave the offenders. Upon the deaths of her sons, Rita again felt the call to religious life. However, some of the sisters at the Augustinian monastery were relatives of her husband’s murderers, and she was denied entry for fear of causing dissension. Asking for the intervention of Saint John the Baptist, Saint Augustine of Hippo, and Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, she managed to bring the warring factions together, not completely, but sufficiently that there was peace, and she was admitted to the monastery of Saint Mary Magdalen at age 36. Rita lived 40 years in the convent, spending her time in prayer and charity, and working for peace in the region. She was devoted to the Passion, and in response to a prayer to suffer as Christ, she received a chronic head wound that appeared to have been caused by a crown of thorns, and which bled for 15 years. -

ANNUAL REPORT JULY 2011 -JULY 2012 Unit 601, DMG Center, 52 Domingo M

BISHOPS-BUSINESSMEN’S CONFERENCE for Human Development ANNUAL REPORT JULY 2011 -JULY 2012 Unit 601, DMG Center, 52 Domingo M. Guevarra St. corner Calbayog Extension Mandaluyong City Tel Nos. 584-25-01; Tel/Fax 470-41-51 E-mail: [email protected] Website: bbc.org.ph TABLE OF CONTENTS BISHOPS-BUSINESSMEN’S CONFERENCE MESSAGE OF NATIONAL CO-CHAIRMEN.....................................................1-2 FOR HUMAN DEVELOPMENT NATIONAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE ELECTION RESULTS............................ 3-4 STRATEGIC PLANNING OF THE EXCOM - OUTPUTS.....................................5-6 NATIONAL EXECUTIVE COMMITEE REPORT.................................................7-10 NATIONAL SECRETARIAT National Greening Program.................................................................8-10 Consultation Meeting with the CBCP Plenary Assembly........................10-13 CARDINAL SIN TRUST FUND FOR BUSINESS DISCIPLESHIP.......................23-24 CLUSTER/COMMITTEE REPORTS Formation of BBC Chapters..........................................................................13 Mary Belle S. Beluan Cluster on Labor & Employment................................................................23-24 Executive Director/Editor Committee on Social Justice & Agrarian Reform.....................................31-37 Coalition Against Corruption -BBC -LAIKO Government Procurement Monitoring Project.......................................................................................38-45 Replication of Government Procurement Monitoring............................46-52 -

On Lav Diaz‟S a Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery

―Textual Mobilities: Diaspora, Migration, Transnationalism and Multiculturalism‖ | Lullaby of Diasporic Time: On Lav Diaz‟s A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery Christian Jil R. Benitez Ateneo de Manila University Philippines [email protected] Abstract Lav Diaz is a Filipino independent filmmaker notable as a key figure in the contemporary slow cinema movement. Of his oeuvre, one of the longest is A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery (Filipino: Hele sa Higawang Hapis), a 2016 epic film that runs for 8 hours, orchestrating narratives derived from what are conveniently sung as mythology (i.e., Jose Rizal‘s El filibusterismo and Philippine folklore) and history (i.e., Philippine history and artifacts). The movie competed in the 66th Berlin International Film Festival, where it won the Alfred Bauer Prize. This success has earned Diaz‘s the spotlight in the Filipino mainstream culture, enabling the film to be distributed to and showcased in mainstream platforms, albeit primarily garnering attention from the Filipino audience for its runtime and international attention. The movement of the film, as a text, from the local Philippines toward the international and returning home, incurs in it a textuality that disrupts the phenomenology of time diasporically, scatteringly: that as much as its 8-hour languor ―opens new perspective in the cinematic arts‖ according to the international rendition of this time, it is also the 8-hour whose value in the Philippine time is that of a day‘s labor, and thus the exoticization of its cinematic experience as a ―challenge,‖ having to endure an entire working day of slow cinematography. This diaspora of time is of no cacophony; on the contrary, it is the lullaby, sorrowful and mysterious, that finally slows Diaz in to become a filmmaker attuned to both the spaces of the local and the international. -

October 2017

St. Mary of the St. Vincent’s ¿ En Que Consiste Angels School Welcomes El Rito Del Ukiah Religious Sisters Exorcismo? Page 21 Page 23 Pagina 18 NORTH COAST CATHOLIC The Newspaper of the Diocese of Santa Rosa • www.srdiocese.org • OCTOBER 2017 Noticias en español, pgs. 18-19 Pope Francis Launches Campaign to Encounter and Since early May Catholics around the diocese have been celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Apparitions of Our Welcome Migrants Lady of the Most Holy Rosary in Fatima. The Rosary: The Peace Plan by Elise Harris from Heaven Catholics are renewing Mary’s Rosary devotion as the Church commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Fatima apparitions by Peter Jesserer Smith (National Catholic Register) “Say the Rosary every day to bring peace to the world promised as the way to end the “war to end all wars.” and the end of the war.” The great guns of World War I have fallen silent, but One hundred years ago at a field in Fatima, Por- these words of Our Lady of the Rosary have endured. tugal, the Blessed Virgin Mary spoke those words to In this centenary year of Our Lady’s apparitions at three shepherd children. One thousand miles away, Fatima, as nations continue to teeter toward war and in the bloodstained fields of France, Europe’s proud strife, Catholics have been making a stronger effort to empires counted hundreds of thousands of their spread the devotion of the Rosary as a powerful way “Find that immigrant, just one, find out who they are,” youth killed and wounded in another battle vainly (see The Rosary, page 4) she said. -

Philippine Studies Ateneo De Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines

philippine studies Ateneo de Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines Bibliography John N. Schumacher, S.J. Philippine Studies vol. 58 nos. 1 & 2 (2010): 297–310 Copyright © Ateneo de Manila University Philippine Studies is published by the Ateneo de Manila University. Contents may not be copied or sent via email or other means to multiple sites and posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s written permission. Users may download and print articles for individual, noncom- mercial use only. However, unless prior permission has been obtained, you may not download an entire issue of a journal, or download multiple copies of articles. Please contact the publisher for any further use of this work at [email protected]. or [email protected]. http://www.philippinestudies.net Bibliography John N. Schumacher, S.J. Books 1970 1. The Catholic Church in the Philippines: Selected readings. Quezon City: Loyola School of Theology. 313 pp. Mimeographed. 1972 2. Father José Burgos: Priest and nationalist. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. xvi, 273 pp. 1973 3. The Propaganda Movement: 1880–1895. The creators of a Filipino consciousness, the makers of the revolution. Manila: Solidaridad Publishing House. xii, 302 pp. 1974 4. Philippine retrospective national bibliography: 1523–1699, comp. Gabriel A. Bernardo and Natividad P. Verzosa, ed. John N. Schumacher, S.J. Manila: National Library of the Philippines; Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. xvi, 160 pp. 1976 5. (With Horacio de la Costa, S.J.) Church and state: The Philippine experience. Loyola Papers 3. Manila: Loyola School of Theology. iv, 64 pp. -

Death by Garrote Waiting in Line at the Security Checkpoint Before Entering

Death by Garrote Waiting in line at the security checkpoint before entering Malacañang, I joined Metrobank Foundation director Chito Sobrepeña and Retired Justice Rodolfo Palattao of the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan who were discussing how to inspire the faculty of the Unibersidad de Manila (formerly City College of Manila) to become outstanding teachers. Ascending the grand staircase leading to the ceremonial hall, I told Justice Palattao that Manuel Quezon never signed a death sentence sent him by the courts because of a story associated with these historic steps. Quezon heard that in December 1896 Jose Rizal's mother climbed these steps on her knees to see the governor-general and plead for her son's life. Teodora Alonso's appeal was ignored and Rizal was executed in Bagumbayan. At the top of the stairs, Justice Palattao said "Kinilabutan naman ako sa kinuwento mo (I had goosebumps listening to your story)." Thus overwhelmed, he missed Juan Luna's Pacto de Sangre, so I asked "Ilan po ang binitay ninyo? (How many people did you sentence to death?)" "Tatlo lang (Only three)", he replied. At that point we were reminded of retired Sandiganbayan Justice Manuel Pamaran who had the fearful reputation as The Hanging Judge. All these morbid thoughts on a cheerful morning came from the morbid historical relics I have been contemplating recently: a piece of black cloth cut from the coat of Rizal wore to his execution, a chipped piece of Rizal's backbone displayed in Fort Santiago that shows where the fatal bullet hit him, a photograph of Ninoy Aquino's bloodstained shirt taken in 1983, the noose used to hand General Yamashita recently found in the bodega of the National Museum. -

8Th Euroseas Conference Vienna, 11–14 August 2015

book of abstracts 8th EuroSEAS Conference Vienna, 11–14 August 2015 http://www.euroseas2015.org contents keynotes 3 round tables 4 film programme 5 panels I. Southeast Asian Studies Past and Present 9 II. Early And (Post)Colonial Histories 11 III. (Trans)Regional Politics 27 IV. Democratization, Local Politics and Ethnicity 38 V. Mobilities, Migration and Translocal Networking 51 VI. (New) Media and Modernities 65 VII. Gender, Youth and the Body 76 VIII. Societal Challenges, Inequality and Conflicts 87 IX. Urban, Rural and Border Dynamics 102 X. Religions in Focus 123 XI. Art, Literature and Music 138 XII. Cultural Heritage and Museum Representations 149 XIII. Natural Resources, the Environment and Costumary Governance 167 XIV. Mixed Panels 189 euroseas 2015 . book of abstracts 3 keynotes Alarms of an Old Alarmist Benedict Anderson Have students of SE Asia become too timid? For example, do young researchers avoid studying the power of the Catholic Hierarchy in the Philippines, the military in Indonesia, and in Bangkok monarchy? Do sociologists and anthropologists fail to write studies of the rising ‘middle classes’ out of boredom or disgust? Who is eager to research the very dangerous drug mafias all over the place? How many track the spread of Western European, Russian, and American arms of all types into SE Asia and the consequences thereof? On the other side, is timidity a part of the decay of European and American universities? Bureaucratic intervention to bind students to work on what their state think is central (Terrorism/Islam)? -

Region IV CALABARZON

Aurora Primary Dr. Norma Palmero Aurora Memorial Hospital Baler Medical Director Dr. Arceli Bayubay Casiguran District Hospital Bgy. Marikit, Casiguran Medical Director 25 beds Ma. Aurora Community Dr. Luisito Te Hospital Bgy. Ma. Aurora Medical Director 15 beds Batangas Primary Dr. Rosalinda S. Manalo Assumpta Medical Hospital A. Bonifacio St., Taal, Batangas Medical Director 12 beds Apacible St., Brgy. II, Calatagan, Batangas Dr. Merle Alonzo Calatagan Medicare Hospital (043) 411-1331 Medical Director 15 beds Dr. Cecilia L.Cayetano Cayetano Medical Clinic Ibaan, 4230 Batangas Medical Director 16 beds Brgy 10, Apacible St., Diane's Maternity And Lying-In Batangas City Ms. Yolanda G. Quiratman Hospital (043) 723-1785 Medical Director 3 beds 7 Galo Reyes St., Lipa City, Mr. Felizardo M. Kison Jr. Dr. Kison's Clinic Batangas Medical Director 10 beds 24 Int. C.M. Recto Avenue, Lipa City, Batangas Mr. Edgardo P. Mendoza Holy Family Medical Clinic (043) 756-2416 Medical Director 15 beds Dr. Venus P. de Grano Laurel Municipal Hospital Brgy. Ticub, Laurel, Batangas Medical Director 10 beds Ilustre Ave., Lemery, Batangas Dr. Evelita M. Macababad Little Angels Medical Hospital (043) 411-1282 Medical Director 20 beds Dr. Dennis J. Buenafe Lobo Municipal Hospital Fabrica, Lobo, Batangas Medical Director 10 beds P. Rinoza St., Nasugbu Doctors General Nasugbu, Batangas Ms. Marilous Sara Ilagan Hospital, Inc. (043) 931-1035 Medical Director 15 beds J. Pastor St., Ibaan, Batangas Dr. Ma. Cecille C. Angelia Queen Mary Hospital (043) 311-2082 Medical Director 10 beds Saint Nicholas Doctors Ms. Rosemarie Marcos Hospital Abelo, San Nicholas, Batangas Medical Director 15 beds Dr. -

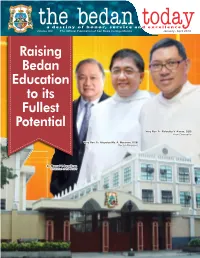

The Bedan Today a D E S T I N Y O F H O N O R, S E R V I C E a N D E X C E L L E N C E Editor in Chief Dr

thea d e s t i n y bedano f h o n o r, s e r v i c e a n dtoday e x c e l l e n c e Volume X IV The Official Publication of San Beda College Manila November January 2014 - April 20152016 Raising Bedan Education to its Fullest Potential Very Rev. Fr. Rafaelito V. Alaras, OSB Prior-Chancellor Very Rev. Fr. Aloysius Ma. A. Maranan, OSB Rector-President Dr. Manuel V. Pangilinan Chairman of the Board the bedan today a d e s t i n y o f h o n o r, s e r v i c e a n d e x c e l l e n c e Editor in Chief Dr. Joffre M. Alajar Contributing Writers Dr. Josefina Manabat Mrs. Teresita Battad Prof. Michael John Rubio Dr. James Loreto Piscos editor'seditor's Mr. Joel Filamor Mr. Jude Roque THE BEDAN TODAY is the official publication of note San Beda College Manila, produced semestrally, note with editorial and business offices at the San Beda Dr. Joffre M. Alajar College Public Relations and Communications Director Office, Mendiola, Manila. Public Relations and Communications Office www.sanbeda.edu.ph Raising Bedan Education to its Fullest Potential The winds of change are being remarkably felt in Philippine Education over the recent months, and these are expected to blow further during the next succeeding years. The K-12 program is prepared to take-off this coming AY 2016-2017. The ASEAN Economic Integration with its concomitant effect on regional educational system is now moving with a surprising speed. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

José Rizal and Benito Pérez Galdós: Writing Spanish Identity in Pascale Casanova’S World Republic of Letters

José Rizal and Benito Pérez Galdós: Writing Spanish Identity in Pascale Casanova’s World Republic of Letters Aaron C. Castroverde Georgia College Abstract: This article will examine the relationship between Casanova’s World Republic of Letters and its critical importance, demonstrating the false dilemma of anti-colonial resistance as either a nationalist or cosmopolitan phenomenon. Her contribution to the field gives scholars a tool for theorizing anti-colonial literature thus paving the way for a new conceptualization of the ‘nation’ itself. As a case study, we will look at the novels of the Filipino writer José Rizal and the Spanish novelist Benito Pérez Galdós. Keywords: Spain – Philippines – José Rizal – Benito Pérez Galdós – World Literature – Pascale Casanova. dialectical history of Pascale Casanova’s ideas could look something like this: Her World Republic of Letters tries to reconcile the contradiction between ‘historical’ (i.e. Post-colonial) reading of literature with the ‘internal’ or A purely literary reading by positing ‘world literary space’ as the resolution. However, the very act of reflecting and speaking of the heterogeneity that is ‘world’ literature (now under the aegis of modernity, whose azimuth is Paris) creates a new gravitational orbit. This synthesis of ‘difference’ into ‘identity’ reveals further contradictions of power and access, which in turn demand further analysis. Is the new paradigm truly better than the old? Or perhaps a better question would be: what are the liberatory possibilities contained within the new paradigm that could not have previously been expressed in the old? *** The following attempt to answer that question will be divided into three parts: first we will look at Rizal’s novel, Noli me tángere, and examine the uneasiness with which the protagonist approached Europe and modernity itself. -

San Lorenzo Ruiz De Manila

Luis Antonio Gokim Tagle, born June The Filipino Apostolate of the 21, 1957, is a Roman Catholic Filipi- Archdiocese of Philadelphia and no cardinal, the 32nd Archbishop of Ma- nila, Cardinal-Priest of the titular church the Filipino Executive Council of San Felice da Cantalice a Centecelle. of Greater Philadelphia He was made a cardinal by Pope Bene- cordially invite you to the dict XVI in a papal consistory on No- vember 24, 2012 at Saint Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City. 28th Annual Celebration of the Feast of Cardinal Tagle is currently a member of the Congregation for Catholic Education, Congregation of the Evangelization of Peoples, Pontifical Council for the Family, Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People, Congre- gation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Consecrated Life, Pontifical Council for the Laity and the XIII Ordinary Council of the Secretariat General of the Synod of Bishops. He was also confirmed by Pope Francis as President of the Catholic Biblical Federation on March 5, 2015. On May 14, 2015, he was elected President of the Caritas Internationalis replacing Cardinal Oscar Rodriguez Maradiaga. And on July 12 he was appointed as member to the Pontifical Council Cor Unum for Human and Christian Development. 6:00 PM Celebration of World Meeting of Families San Lorenzo Ruiz de Manila 7:00 PM Mass His Eminence, Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle Archbishop of Manila Main Celebrant and Homilist First Filipino Martyr and Saint For more information, kindly call: on Thursday, September 24, 2015 at 7:00 pm Fr.