Baseline Household Survey Multan 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders (W/Out Cnic) As of December 31, 2017

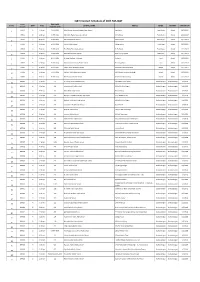

ASKARI BANK LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS (W/OUT CNIC) AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2017 S. NO. FOLIO NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDERS ADDRESSES OF THE SHAREHOLDERS NO. OF SHARES 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN C/O BANK OF AMERICA, BLUE AREA, ISLAMABAD. 2878 12 68 MR. WASEEM AHMED HOUSE NO.485, STREET NO.17, CHAKLALA SCHEME-III, RAWALPINDI. 5945 13 71 MS. SHAMEEM QUAVI SIDDIQUI 112/1, 13TH STREET, PHASE-VI, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI-75500. 2695 14 74 MS. YAZDANI BEGUM HOUSE NO.A-75, BLOCK-13, GULSHAN-E-IQBAL, KARACHI. -

Code Name Cnic No./Passport No. Name Address

Format for Reporting of Unclaimed Deposits. Instruments Surrendered to SBP Period of Surrendered (2016): Bank Code: 1279 Bank Name : THE PUNJAB PROVINCIAL COOPERATIVE BANK LIMITED HEAD OFFICE LAHORE Last date of DETAIL OF THE BRANCH NAME OF THE PROVINCE IN DETAIL OF THE DEPOSTOER BENEFICIARY OF THE INSTRUMENT DETAIL OF THE ACCOUNT DETAIL OF THE INSTRUMENT TRANSACTION deposit or WHICH ACCOUNT NATURE ACCOUNT Federal. Curren Rate FCS Rat Rate NAME OF THE INSTRUMENT Remarks S.NO CNIC NO./PASSPORT OF THE TYPE ( e.g INSTRUME DATE OF Provincial cy Type. Contract e Appli Amount Eqr. PKR withdrawal CODE NAME OPENED.INSTRUMENT NAME ADDRESS ACCOUNT NUMBER APPICANT. TYPE (DD, PO, NO. DEPOSIT CURRENT NT NO. ISSUE (FED.PRO)I (USD, ( No (if of ed Outstanding surrendered (DD-MON- PAYABLE PURCHASER FDD, TDR, CO) (LCY,UF , SAVING , n case of EUR, MTM, any) PK date YYYY) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 1 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8695206-3 KAMAL-UD-DIN S.O ALLAH BUKHSH ARCS SAHIWAL, TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011001 PLS PKR 1,032.00 1,032.00 18/07/2005 2 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8795426-9 ALI MUHAMMAD S.O IMAM DIN H. NO. 196 FAREED TOWN SAHIWAL,TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011101 PLS PKR 413.00 413.00 11/07/2005 3 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-8395698-7 MUHAMMAD SALEEM CHAK NO. 80.6-R TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011301 PLS PKR 1,656.00 1,656.00 08/03/2005 4 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-3511981-9 ABDUL GHANI S.O ALLAH DITTA FARID TOWN 515.K ,TEHSIL & DISTRICT SAHIWAL LCY 15400100011501 PLS PKR 942.00 942.00 04/11/2005 5 321 SAHIWAL DC PB 36502-9956978-9 SHABBIR AHMAD S.O MUHAMMAD RAMZAN CHAK NO. -

Final Schedule of 18Th FAS-QAT.Xlsx

QAT Conduct Schedule of 18th FAS‐QAT Cluster EMIS CODE Sr. No. SHIFT Time SCHOOL_NAME Address TEHSIL DISTRICT DATE OF QAT Number / SCHOOL CODE ATK01 A 9.00 am 9‐ATK‐0009 Misali Arqum Science Academy/Sec School Vpo Ikhlas Pindi Ghaib Attock 12/11/2017 1 ATK01 B 12.30 pm 9‐ATK‐0011 Pak Public Higher Secondary School V.P.O Ikhlas Pindi Ghaib Attock 12/11/2017 2 ATK02 A 9.00 am 6‐ATK‐0022 The Village Model School Ikhlas Chowk Pindi Ghaib Attock 12/11/2017 3 ATK03 B 12.30 pm 6‐ATK‐0028 Minhaj Public School Village Hattar Fateh Jang Attock 12/11/2017 4 ATK03 A 9.00 am 7‐ATK‐0026 Fine Public Elementary School V. Po Hattar Fateh Jang Attock 12/11/2017 5 ATK04 A 9.00 am 6‐ATK‐0030 New Mehran Public School Near T.H.Q Hospital Fateh Jang Attock 12/11/2017 6 ATK05 A 9.00 am 8‐ATK‐0004 Al‐Huda Madrasa‐Tul‐Banat R.S Injra Jand Attock 12/11/2017 7 ATK05 B 12.30 pm 9‐ATK‐0014 Muhammad Ali Islamia Public School P.O Village Kani Jand Attock 12/11/2017 8 ATK06 A 9.00 am 9‐ATK‐0004 Green Land Elementary School Mohallah Shah Faisal Abad Attock Attock 12/11/2017 9 ATK06 B 12.30 pm 9‐ATK‐0006 Modern Public Elementary School Moh.Masjid Usmania Shinbagh Attock Attock 12/11/2017 10 ATK07 A 9.00 am 9‐ATK‐0010 Faiz Grammar Public School New Town Bihar Colony Attock Attock 12/11/2017 11 BWN01 A 9.00 am 54 Al Hurmat Public Middle School Qaimabad Canal Colony Bahawalnagar Bahawalnagar 1/3/2018 12 BWN01 B 12.30 pm 216 Fatima Jinnah Public School Mohallah Islam Nagar Bahawalnagar Bahawalnagar 1/3/2018 13 BWN02 A 9.00 am 55 Faisal Public High School Faisal Colony Bahawalnagar -

List of Stations

Sr # Code Division Name of Retail Outlet Site Category City / District / Area Address 1 101535 Karachi AHMED SERVICE STATION N/V CF KARACHI EAST DADABHOY NOROJI ROAD AKASHMIR ROAD 2 101536 Karachi CHAND SUPER SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI WEST PSO RETAIL DEALERSST/1-A BLOCK 17F 3 101537 Karachi GLOBAL PETROLEUM SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI EAST PLOT NO. 234SECTOR NO.3, 4 101538 Karachi FAISAL SERVICE STATION N/V CF KARACHI WEST ST 1-A BLOCK 6FEDERAL B AREADISTT K 5 101540 Karachi RAANA GASOLINE N/V CF KARACHI WEST SERVICE STATIONPSO RETAIL DEALERAPWA SCHOOL LIAQA 6 101543 Karachi SHAHGHAZI P/S N/V DFA MALIR SURVEY#81,45/ 46 KM SUPER HIGHWAY 7 101544 Karachi GARDEN PETROL SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI SOUTH OPP FATIMA JINNAHGIRLS HIGH SCHOOLN 8 101545 Karachi RAZA PETROL SERVICE N/V CF KARACHI SOUTH 282/2 LAWRENCE ROADKARACHIDISTT KARACHI-SOUTH 9 101548 Karachi FANCY SERVICE STATION N/V CF KARACHI WEST ST-1A BLOCK 10FEDERAL B AREADISTT KARACHI WEST 10 101550 Karachi SIDDIQI SERVIC STATION S/S DFB KARACHI EAST RASHID MINHAS ROADKARACHIDISTT KARACHI EAST 11 101555 Karachi EASTERN SERIVCE STN N/V DFA KARACHI WEST D-201 SITEDIST KARACHI-WEST 12 101562 Karachi AL-YASIN FILL STN N/V DFA KARACHI WEST ST-1/2 15-A/1 NORTHKAR TOWNSHIP KAR WEST 13 101563 Karachi DUREJI FILLING STATION S/S DFA LASBELA KM-4/5 HUB-DUREJI RDPATHRO HUBLASBE 14 101566 Karachi R C D FILLING STATION N/V DFA LASBELA HUB CHOWKI LASBELADISTT LASBELA 15 101573 Karachi FAROOQ SERVICE CENTRE N/V CF KARACHI WEST N SIDDIQ ALI KHAN ROADCHOWRANGI NO-3NAZIMABADDISTT 16 101577 Karachi METRO SERVICE STATION -

Renewal List

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S NAME PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 21230 ALI AHMAD KHAN ABDUL MOHIT 122/8-M, STREET. NO.2CHAH BOHARWALA,, 14/4/1941 B.A 11/07/2014 KHAN MULTAN, PUNJAB 2 27570 NAHEED RASOOL GHULAM RASOOL GHUNGI NO. 07. H/NO. 64-A MULTAN , 7-9-1979 MATRIC 12/07/2014 MULTAN, PUNJAB 3 28469 AFZAL HUSSAIN KHADIM HUSSAIN SABIR MEDICAL CENTER OUT SIDEHARAM 4-8-1965 MATRIC 13/07/2014 GATE AKBAR ROAD , MULTAN, PUNJAB 4 21473 HAJI ABDUL HAJI KHAIR WARD NO. 06, SHER SHAH ROAD MOH, 10/1/1961 F.A 14/07/2014 HAMEED KHAN MUHAMMAD KHAN KHUDA DAD COLONY JOHAR , MULTAN, PUNJAB 5 26275 KHALID MEHBOOB SAEED-UD-DIN NEAR AL-JEELUN SCHOOL SURJ KUND RAOD 1-11-1966 MATRIC 14/07/2014 MULTAN , MULTAN, PUNJAB 6 21471 MANZHAR IQBAL ABDUL MAJEED H 764 DELHI GATE, MULTAN, PUNJAB 1/1/1970 MATRIC 14/07/2014 7 41123 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD H/NO. 32 ST, NO. 2 BLOCK Y NEW MULTAN, 7-8-1982 MATRIC 15/7/2014 USMAN SANI YOUSAF MULTAN, PUNJAB 8 27128 ASHFAQ HUSSAIN NAZAR MOH, CHAH DARKHAN WALA JALAL PUR 24-10- MATRIC 15/07/2014 MUHAMMAD PIRWALA DISTT, MULTAN , MULTAN, PUNJAB 1962 9 48463 RABIA PARVEEN SIRAJ DIN H/NO. 14 STREET, C BLOCK Y NEW , MULTAN, 16-2-1985 FA 15/07/2014 PUNJAB 10 46725 MUHAMMAD IMRAN NIAZ MUHAMMAD H NO 102 ZUBAIR COLONY FAROOQ PURA 21/7/1977 MATRIC 15/07/2014 NIAZ OLD SHUJA BAD ROAD , MULTAN, PUNJAB 11 39614 ABDUR RAUF ABDUL LATIF H/NO. -

Chief Minister Self Employment Scheme for Unemployed Educated Youth

Winner List Chief Minister Self Employment Scheme for Unemployed Educated Youth Multan Division NIC ApplicantName GuardianName Address WinOrder Distt. Khanewal Jahanian (Bolan) Key Used: aghakhurm 3610102439763 ABDUL HAFEEZ M. HANIF 105/10R JAHANIAN DIST. 1 3610102595791 LIAQAT HUSSAIN ABDUL HAMEED THATA SADIQABAD, TEH JAHANIA, 2 DISTT. KHANWALA 3610102707797 GHAZANFAR HASSAN MOHAMMAD SHAKAR H NO. 225, BLOCK NO. 5, JAHANIAN 3 DISTT. KHANEWAL. 3610180513779 WASEEM ALI M. SARWAR CHAK NO. 121/10-R TEH. JAHANIA 4 DISTT. KHANEWAL 3520227188361 MOHAMMAD JAVED MOHAMMAD SHAFI FLAT NO 752C BLOCK Q MODEL TOWN 5 LAHORE 3610141795247 Muhammad Shahid Shahzada Zahid Raza Rahim Shah Road H/NO.164/A Jinnah 6 Abdil Jahanian D 3610132117859 MUHAMMAD DILSHAD ALI JAMSHAD ALI CHAK NO. 135/10R, TEHSEEL 7 JAHANIAN DISTT. KHANEWAL 3610102391383 TAHIR ABBAS AZIZ AHMED CHAK KHRIA POST 99-10R RAHEEM 8 SHAH 3610180588801 SOHAIL IJAZ IAJZ AHMED CHAK NO 116/10-R NEW TEH 9 JAHANIAN KHANEWAL 3610112010659 MOHAMMAD RIAZ FALIK SHER CHAK NO 157/10-R P/O JUNGLE 10 MARYALA JHASIL JAHANIA 3610166557189 MUHAMMAD THIR MUHAMMAD SLEEM CAHK NO 135/10R 11 3610171420543 TOQEER HUSSAIN SAEED SAEED AKHTAR CHAK NO. 132/10R, P.O. THATHA 12 SADIQ ABAD TEH JHANI 3610102461071 MUHAMMAD NASRULLAH KHUSHI MUHAMMAD BLOCK # 4 JAHANIAN KWL 13 3610181422213 HAFIZ ASIF JAVED ABDUL GHAFAR CHAK NO. 107/10-R TEH. JAHANIAN 14 DISTT. KHANEWAL 3610115748627 MUHAMMAD ASIF MUHAMMAD RAMZAN CHAK NO 114-10R JAHIANIAN DIST 15 KHANEWAL 3610154828857 ASIF BASHIR BASHIR AHMAD MAMTAZ LAKR MANDI TEH. JAHANIAN DISTT. 16 KHANEWAL 3610102391373 MUHAMMAD SARWAR MUHAMMAD NAZIR AHMED OPP BHATTI SERVICE STATION SIAL 17 TOWN JHN TEH JHN D 3610102750511 ASIF ISMAIL LIAQAT ALI CH. -

Audit Reports on the Accounts of Town Municipal Administrations City District Governmentmultan

AUDIT REPORTS ON THE ACCOUNTS OF TOWN MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATIONS CITY DISTRICT GOVERNMENTMULTAN AUDIT YEARS 2009-2012 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ....................................................................... i PREFACE ....................................................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................iii SUMMARY TABLES AND CHARTS ...................................................................... vii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics ....................................................................................... vii Table 2: Audit Observations .......................................................................................... vii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ...........................................................................................viii Table 4: Irregularities pointed out .................................................................................viii CHAPTER 1 ................................................................................................................... 1 1. TOWN MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATIONS, CITY DISTRICT MULTAN ....... 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) ................................. 2 1.2 Town Municipal Administration, Shah Rukn-e-Alam ................................ -

Deployed Staff of Pec G-8, for the Year 2020 District Multan

DEPLOYED STAFF OF PEC G-8, FOR THE YEAR 2020 DISTRICT MULTAN exam_c tehsil cluster teacher teacher EMIS Of enter_c exam_center_name duty teacher CNIC school_name_Of_Teacher _name Name Name Contact Teacher ode JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR 101 RI Muhammad Abid 3630109450761 3017436747 GHSS JALALPUR PIRWALA 36140001 PIRWALA PIRWALA PIRWALA (A) JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR 101 Superintendent Tumkeen Saim 3630151913759 3077456604 GHS RASOOL PUR 1 SHUJABAD 36120036 PIRWALA PIRWALA PIRWALA (A) JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR Dy. GHS HAFIZ WALA JALALPUR 101 Rajab Ali Malik 3630109282323 3002860417 36140007 PIRWALA PIRWALA PIRWALA (A) Superintendent PIRWALA JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR Muhammad Asif GHS HAFIZ WALA JALALPUR 101 Invigilator 3630109818061 3017428674 36140007 PIRWALA PIRWALA PIRWALA (A) Mansoor PIRWALA JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR 101 Invigilator Muhammad Sarwar 3630109249231 3015893582 GMPS KHALIL ABAD 36140160 PIRWALA PIRWALA PIRWALA (A) JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR GES JALAL PUR PIRWALA NO.1 101 Invigilator Nazir Ahmad 3630109817977 3036458864 36140046 PIRWALA PIRWALA PIRWALA (A) WARD NO 4 JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR 101 Invigilator Ghulam Ali 6110117997917 3007364859 GES 86/M JALALPUR PIRWALA 36140329 PIRWALA PIRWALA PIRWALA (A) JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR Muhammad Khuram 101 Invigilator 3630175975193 3007808179 GPS PIR WALA 36140074 PIRWALA PIRWALA PIRWALA (A) Hassam JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR GHSS JALALPUR GHS HAFIZ WALA JALALPUR 101 Invigilator Muhammad Asif Javed 3630157904661 -

Appendix - II Pakistani Banks and Their Branches (December 31, 2008)

Appendix - II Pakistani Banks and their Branches (December 31, 2008) Allied Bank Ltd. Bhalwal (2) Chishtian (2) -Grain Market -Grain Market (743) -Noor Hayat Colony -Mohar Sharif Road Abbaspur 251 RB Bandla Bheli Bhattar (A.K.) Chitral Chungpur (A.K.) Abbottabad (4) Burewala (2) Dadu -Bara Towers, Jinnahabad -Grain Market -Pineview Road -Housing Scheme Dadyal (A.K) (2) -Supply Bazar -College Road -The Mall Chak Jhumra -Samahni Ratta Cross Chak Naurang Adda Johal Chak No. 111 P Daharki Adda Nandipur Rasoolpur Chak No. 122/JB Nurpur Danna (A.K.) Bhal Chak No. 142/P Bangla Danyor Adda Pansra Manthar Darband Adda Sarai Mochiwal Chak No. 220 RB Dargai Adda Thikriwala Chak No. 272 HR Fortabbas Darhal Gaggan Ahmed Pur East Chak No. 280/JB (Dawakhri) Daroo Jabagai Kombar Akalgarh (A.K) Chak No. 34/TDA Daska Arifwala Chak No. 354 Daurandi (A.K.) Attock (Campbellpur) Chak No. 44/N.B. Deenpur Bagh (A.K) Chak No. 509 GB Deh Uddhi Bahawalnagar Chak No. 76 RB Dinga Chak No. 80 SB Bahawalpur (5) Chak No. 88/10 R Dera Ghazi Khan (2) Chak No. 89/6-R -Com. Area Sattelite Town -Azmat Road -Dubai Chowk -Model Town -Farid Gate Chakwal (2) -Ghalla Mandi -Mohra Chinna Dera Ismail Khan (3) -Settelite Town -Talagang Road -Circular Road -Commissionery Bazar Bakhar Jamali Mori Talu Chaman -Faqirani Gate (Muryali) Balagarhi Chaprar Balakot Charsadda Dhamke (Faisalabad) Baldher Chaskswari (A.K) Dhamke (Sheikhupura) Bucheke Chattar (A.K) Dhangar Bala (A.K) Chhatro (A.K.) Dheed Wal Bannu (2) Dina -Chai Bazar (Ghalla Mandi) Chichawatni (2) Dipalpur -Preedy Gate -College Road Dir Barja Jandala (A.K) -Railway Road Dunyapur Batkhela Ellahabad Behari Agla Mohra (A.K.) Chilas Eminabad More Bewal Bhagowal Faisalabad (20) Bhakkar Chiniot (2) -Akbarabad Bhaleki (Phularwan Chowk) -Muslim Bazar (Main) -Sargodha Road -Chibban Road 415 ABL -Factory Area -Zia Plaza Gt Road Islamabad (23) -Ghulam Muhammad Abad Colony Gujrat (3) -I-9 Industrial Area -Gole Cloth Market -Grand Trunk Road -Aabpara -Gole Kiryana Bazar -Rehman Saheed Road -Blue Area ABL -Gulburg Colony -Shah Daula Road. -

__7Etilv^ ( Syed Safeer Hussain )

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Islamic Republic of Pakistan 2nd Floor, OPF Building, G-5/2, Islamabad Ph: 9206500, 9207200, Fax: 9210215 E-mail: [email protected] Registrar No. NEPRA/TRF-175/MEPCO-2011/01-03 January 2, 2012 Subject: Determination of the Authority in the matter of Petition filed by Multan Electric Power Company Ltd. for Determination of its Consumer end Tariff Pertaining to the FY 2011-12 [Case # NEPRA/TRF-175/MEPCO-2011 Intimation of Determination of Tariff pursuant to Section 31(4) of the Regulation of Generation, Transmission and Distribution of Electric Power Act (XL of 1997 Dear Sir, Please find enclosed herewith the subject Determination of the Authority along with Annexure-I, II, III, IV & V (64 pages) in Case No. NEPRA/TRF-175/MEPCO-2011. 2. The Determination is being intimated to the Federal Government for the purpose of notification of the approved tariff in the official gazette pursuant to Section 31(4) of the Regulation of Generation, Transmission and Distribution of Electric Power Act (XL of 1997) and Rule 16(11) of the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (Tariff Standards and Procedure) Rules, 1998. 3. Please note that only the Order of the Authority at para 25 of the Determination along with Annexure-I (Fuel Price Adjustment Mechanism), Annex-III (Schedule of Electricity Tariffs), Annex-IV (CpGenE, CpGenCap & USCF) and Annex-V (Terms and Conditions) needs to be notified in the official Gazette. Enclosure: As above __7Etilv^ ( Syed Safeer Hussain ) Secretary Ministry of Water & Power `A' Block, Pak Secretariat Islamabad CC: 1. Secretary, Cabinet Division, Cabinet Secretariat , Islamabad. -

Town Municipal Administration, Musa Pak Shaheed Town, Multan

Town Municipal Administration, Musa Pak Shaheed Town, Multan. TENDER NOTICE Town Municipal Administration Musa Pak Shaheed Town Multan intends to invite tenders for its development program as per Government of Punjab LG & CD Development Notification No.SOR(LG)48/2002 dated 28-02-2012. Such contractors who have deposited their registration fee for financial year 2012-13 in any TMA of Multan District. Tender form can be received upto 01.11.2012 free of cost from the office of Town Officer (I&S) or website of LG& CD Department. Tender form along with 2% CDR issued from any schedule Bank of Pakistan will be received on 03.11.2012 upto 1:00 P.M. Received tenders will be opened on the same day in the presence of contractors or their authorized representative. It will be compulsory for all the contractors to quote their rates in words and digits as well. Rates will be quoted in % above or below on estimated cost. Such tenders which do not fulfill the instructions issued by government will be considered as cancelled. The contractors will be bound to deposit 10% performance security along with deposited 2% CDR within 7 days of acceptance of tenders. If the contractor does not deposit the performance security in due time, their deposited CDR will be forfeited in favor of TMA and tenders will be called again. No excuse of the contractors will be acceptable after acceptance of tenders. The contractor will be bound to do in agreement on prescribed stamp paper and start work at site within 7 days. -

Institution Wise Pass Percentage SSC 9Th Annual

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE & SECONDARY EDUCATION, MULTAN A- 1 INSTITUTION WISE PASS PERCENTAGE AND GRADING 9TH EXAM 2016 Appeared Passed Pass% Appeared Passed Pass% 101001 Govt. Girls English Medium Model 101026 Govt. Girls High School 80/10-R High School, Khanewal Pirowal, Khanewal 751 431 57.39 67 30 44.78 101002 Govt. M.C .E/M Girls High School, 101028 GOVT. GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL BAGAR Khanewal SARGANA, Kabirwala 196 105 53.57 27 16 59.26 101003 Govt. Girls High School, 101029 Govt. Girls High School Nanakpur Kabirwala ,Khanewal 375 136 36.27 47 16 34.04 101004 Govt. Girls Model High School, 101030 Govt. Girls Hassan Model High Mian Channu School, Khanewal. 569 358 62.92 266 175 65.79 101005 Govt. Girls E/M High School, 101031 Govt. Girls High School 92/10.R, Jahanian Khanewal 352 147 41.76 29 17 58.62 101008 Govt. Methodist Girls High School 101032 Govt. Girls High School, 28/10-R 135/16-L, Khanewal ,Khanewal 79 23 29.11 31 23 74.19 101010 Govt. Girls High School 136/10-R, 101033 Govt. Girls High School 23/10-R, Khanewal Khanewal 79 41 51.90 61 37 60.66 101011 Govt. Girls E/M High School, 101034 Govt. Girls High School, 72/10-R 138/10-R, Jahanian ,Khanewal 118 95 80.51 18 3 16.67 101012 Govt. Girls High School, 12/A.H. 101035 Govt. Girls High School, 116/15-L ,Khanewal Mainchannu ,Khanewal 101 74 73.27 30 22 73.33 101013 Govt. Girls High School Sarai 101036 Govt.