Historic Photographs of Glaciers and Glacial Landforms from the R. S. Tarr Collection at Cornell University Julie Elliott1, Matthew E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

Hubbard Glacier

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior Hubbard Glacier Hubbard Glacier Fact Sheet --The Hubbard Glacier is North America’s largest tidewater glacier. It is 76 miles long, 7 miles wide, and 600 feet tall at its terminal face (350 feet exposed above the waterline and 250 feet below the waterline). --The Hubbard Glacier starts at Mt. Logan (19850 ft) in the Yukon Territory. Mt. Logan is the 2nd tallest mountain on the North American continent. --The Hubbard Glacier is currently advanc- ing (last 100 years), while most Alaskan glaciers are retreating (95%). This is not in contradiction with current global tempera- ture increases. The Hubbard Glacier will advance during times of warming climate and retreat in time of colder climates. The The Hubbard Glacier (right) and the Turner Glacier looking from Russell Fjord. current rate of advance is approximately 80 feet per year. 700 years ago – advanced to fill the entire pressure applied from the snow accumulat- --The glacier’s rate of overall forward ve- Yakutat Bay ing above. locity is much higher, but the advance is due its calving. Why do glaciers advance and retreat? --Once the ice becomes more than 150 feet thick the ice can behave plastically, and --The ice you see at the terminal face is ap- --Glaciers will always try to reach a balance start to flow under the influence of gravity. proximately 450 years old and is over 2000 between the amount of ice they gain to feet thick at some locations. the amount of ice they lose (equilibrium). -

Public Law 96-487 (ANILCA)

APPENDlX - ANILCA 587 94 STAT. 2418 PUBLIC LAW 96-487-DEC. 2, 1980 16 usc 1132 (2) Andreafsky Wilderness of approximately one million note. three hundred thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge" dated April 1980; 16 usc 1132 {3) Arctic Wildlife Refuge Wilderness of approximately note. eight million acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "ArcticNational Wildlife Refuge" dated August 1980; (4) 16 usc 1132 Becharof Wilderness of approximately four hundred note. thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "BecharofNational Wildlife Refuge" dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 (5) Innoko Wilderness of approximately one million two note. hundred and forty thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Innoko National Wildlife Refuge", dated October 1978; 16 usc 1132 (6} Izembek Wilderness of approximately three hundred note. thousand acres as �enerally depicted on a map entitied 16 usc 1132 "Izembek Wilderness , dated October 1978; note. (7) Kenai Wilderness of approximately one million three hundred and fifty thousand acres as generaJly depicted on a map entitled "KenaiNational Wildlife Refuge", dated October 16 usc 1132 1978; note. (8) Koyukuk Wilderness of approximately four hundred thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "KoxukukNational Wildlife Refuge", dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 (9) Nunivak Wilderness of approximately six hundred note. thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Yukon DeltaNational Wildlife Refuge", dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 {10} Togiak Wilderness of approximately two million two note. hundred and seventy thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Togiak National Wildlife Refuge", dated July 16 usc 1132 1980; note. -

Impact of Climate Change in Kalabaland Glacier from 2000 to 2013 S

The Asian Review of Civil Engineering ISSN: 2249 - 6203 Vol. 3 No. 1, 2014, pp. 8-13 © The Research Publication, www.trp.org.in Impact of Climate Change in Kalabaland Glacier from 2000 to 2013 S. Rahul Singh1 and Renu Dhir2 1Reaserch Scholar, 2Associate Professor, Department of CSE, NIT, Jalandhar - 144 011, Pubjab, India E-mail: [email protected] (Received on 16 March 2014 and accepted on 26 June 2014) Abstract - Glaciers are the coolers of the planet earth and the of the clearest indicators of alterations in regional climate, lifeline of many of the world’s major rivers. They contain since they are governed by changes in accumulation (from about 75% of the Earth’s fresh water and are a source of major snowfall) and ablation (by melting of ice). The difference rivers. The interaction between glaciers and climate represents between accumulation and ablation or the mass balance a particularly sensitive approach. On the global scale, air is crucial to the health of a glacier. GSI (op cit) has given temperature is considered to be the most important factor details about Gangotri, Bandarpunch, Jaundar Bamak, Jhajju reflecting glacier retreat, but this has not been demonstrated Bamak, Tilku, Chipa ,Sara Umga Gangstang, Tingal Goh for tropical glaciers. Mass balance studies of glaciers indicate Panchi nala I , Dokriani, Chaurabari and other glaciers of that the contributions of all mountain glaciers to rising sea Himalaya. Raina and Srivastava (2008) in their ‘Glacial Atlas level during the last century to be 0.2 to 0.4 mm/yr. Global mean temperature has risen by just over 0.60 C over the last of India’ have documented various aspects of the Himalayan century with accelerated warming in the last 10-15 years. -

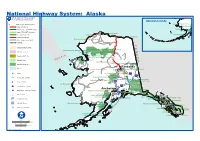

National Highway System: Alaska U.S

National Highway System: Alaska U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration Aleutian Islands Eisenhower Interstate System Lake Clark National Preserve Lake Clark Wilderness Other NHS Routes Non-Interstate STRAHNET Route Katmai National Preserve Katmai Wilderness Major STRAHNET Connector Lonely Distant Early Warning Station Intermodal Connector Wainwright Dew Station Aniakchak National Preserve Barter Island Long Range Radar Site Unbuilt NHS Routes Other Roads (not on NHS) Point Lay Distant Early Warning Station Railroad CC Census Urbanized Areas AA Noatak Wilderness Gates of the Arctic National Park Cape Krusenstern National Monument NN Indian Reservation Noatak National Preserve Gates of the Arctic Wilderness Kobuk Valley National Park AA Department of Defense Kobuk Valley Wilderness AA D II Gates of the Arctic National Preserve 65 D SSSS UU A National Forest RR Bering Land Bridge National Preserve A Indian Mountain Research Site Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Park Service College Fairbanks Water Campion Air Force Station Fairbanks Fortymile Wild And Scenic River Fort Wainwright Fort Greely (Scheduled to close) Airport A2 4 Denali National Park A1 Intercity Bus Terminal Denali National PreserveDenali Wilderness Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park and Preserve Tatalina Long Range Radar Site Wrangell-Saint Elias National Preserve Ferry Terminal A4 Cape Romanzof Long Range Radar Site Truck/Pipeline Terminal A1 Anchorage 4 Wrangell-Saint Elias Wilderness Multipurpose Passenger Facility Sparrevohn Long -

Protecting the Crown: a Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park

Protecting the Crown A Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) RM-CESU Cooperative Agreement H2380040001 (WASO) RM-CESU Task Agreement J1434080053 Theodore Catton, Principal Investigator University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Diane Krahe, Researcher University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Deirdre K. Shaw NPS Key Official and Curator Glacier National Park West Glacier, Montana 59936 June 2011 Table of Contents List of Maps and Photographs v Introduction: Protecting the Crown 1 Chapter 1: A Homeland and a Frontier 5 Chapter 2: A Reservoir of Nature 23 Chapter 3: A Complete Sanctuary 57 Chapter 4: A Vignette of Primitive America 103 Chapter 5: A Sustainable Ecosystem 179 Conclusion: Preserving Different Natures 245 Bibliography 249 Index 261 List of Maps and Photographs MAPS Glacier National Park 22 Threats to Glacier National Park 168 PHOTOGRAPHS Cover - hikers going to Grinnell Glacier, 1930s, HPC 001581 Introduction – Three buses on Going-to-the-Sun Road, 1937, GNPA 11829 1 1.1 Two Cultural Legacies – McDonald family, GNPA 64 5 1.2 Indian Use and Occupancy – unidentified couple by lake, GNPA 24 7 1.3 Scientific Exploration – George B. Grinnell, Web 12 1.4 New Forms of Resource Use – group with stringer of fish, GNPA 551 14 2.1 A Foundation in Law – ranger at check station, GNPA 2874 23 2.2 An Emphasis on Law Enforcement – two park employees on hotel porch, 1915 HPC 001037 25 2.3 Stocking the Park – men with dead mountain lions, GNPA 9199 31 2.4 Balancing Preservation and Use – road-building contractors, 1924, GNPA 304 40 2.5 Forest Protection – Half Moon Fire, 1929, GNPA 11818 45 2.6 Properties on Lake McDonald – cabin in Apgar, Web 54 3.1 A Background of Construction – gas shovel, GTSR, 1937, GNPA 11647 57 3.2 Wildlife Studies in the 1930s – George M. -

Terminal Zone Glacial Sediment Transfer at a Temperate Overdeepened Glacier System Swift, D

University of Dundee Terminal zone glacial sediment transfer at a temperate overdeepened glacier system Swift, D. A.; Cook, S. J.; Graham, D. J.; Midgley, N. G.; Fallick, A. E.; Storrar, R. Published in: Quaternary Science Reviews DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.11.027 Publication date: 2018 Licence: CC BY-NC-ND Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Swift, D. A., Cook, S. J., Graham, D. J., Midgley, N. G., Fallick, A. E., Storrar, R., Toubes Rodrigo, M., & Evans, D. J. A. (2018). Terminal zone glacial sediment transfer at a temperate overdeepened glacier system. Quaternary Science Reviews, 180, 111-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.11.027 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Quaternary Science Reviews 180 (2018) 111e131 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Terminal zone glacial sediment transfer at a temperate overdeepened glacier system * D.A. -

Straddling the Arctic Circle in the East Central Part of the State, Yukon Flats Is Alaska's Largest Interior Valley

Straddling the Arctic Circle in the east central part of the State, Yukon Flats is Alaska's largest Interior valley. The Yukon River, fifth largest in North America and 2,300 miles long from its source in Canada to its mouth in the Bering Sea, bisects the broad, level flood- plain of Yukon Flats for 290 miles. More than 40,000 shallow lakes and ponds averaging 23 acres each dot the floodplain and more than 25,000 miles of streams traverse the lowland regions. Upland terrain, where lakes are few or absent, is the source of drainage systems im- portant to the perpetuation of the adequate processes and wetland ecology of the Flats. More than 10 major streams, including the Porcupine River with its headwaters in Canada, cross the floodplain before discharging into the Yukon River. Extensive flooding of low- land areas plays a dominant role in the ecology of the river as it is the primary source of water for the many lakes and ponds of the Yukon Flats basin. Summer temperatures are higher than at any other place of com- parable latitude in North America, with temperatures frequently reaching into the 80's. Conversely, the protective mountains which make possible the high summer temperatures create a giant natural frost pocket where winter temperatures approach the coldest of any inhabited area. While the growing season is short, averaging about 80 days, long hours of sunlight produce a rich growth of aquatic vegeta- tion in the lakes and ponds. Soils are underlain with permafrost rang- ing from less than a foot to several feet, which contributes to pond permanence as percolation is slight and loss of water is primarily due to transpiration and evaporation. -

The Impact of Glacier Geometry on Meltwater Plume Structure and Submarine Melt in Greenland Fjords

PUBLICATIONS Geophysical Research Letters RESEARCH LETTER The impact of glacier geometry on meltwater 10.1002/2016GL070170 plume structure and submarine melt Key Points: in Greenland fjords • We simulate subglacial plumes and submarine melt in 12 Greenland fjords D. Carroll1, D. A. Sutherland1, B. Hudson2, T. Moon1,3, G. A. Catania4,5, E. L. Shroyer6, J. D. Nash6, spanning grounding line depths from 4,5 4,5 7 8 8 100 to 850 m T. C. Bartholomaus , D. Felikson , L. A. Stearns , B. P. Y. Noël , and M. R. van den Broeke • Deep glaciers produce warm, salty 1 2 subsurface plumes that undercut ice; Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon, USA, Applied Physics Laboratory, University of shallow glaciers drive cold, fresh Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA, 3Bristol Glaciology Centre, School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, surface plumes that can overcut Bristol, UK, 4Institute for Geophysics, University of Texas, Austin, Texas, USA, 5Department of Geology, University of Texas, • Plumes in cold, shallow fjords can Austin, Texas, USA, 6College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA, induce comparable depth-averaged 7 8 melt rates to warm, deep fjords due to Department of Geology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA, Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research sustained upwelling velocities Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands Supporting Information: Abstract Meltwater from the Greenland Ice Sheet often drains subglacially into fjords, driving upwelling • Supporting Information S1 plumes at glacier termini. Ocean models and observations of submarine termini suggest that plumes Correspondence to: enhance melt and undercutting, leading to calving and potential glacier destabilization. -

Alaska Subsistence Fisheries 2003 Annual Report

ALASKA SUBSISTENCE FISHERIES 2003 ANNUAL REPORT Division of Subsistence Alaska Department of Fish and Game Juneau, Alaska September 2005 ALASKA SUBSISTENCE FISHERIES 2003 ANNUAL REPORT Division of Subsistence Alaska Department of Fish and Game Juneau, Alaska September 2005 The Alaska Department of Fish and Game administers all programs and activities free from discrimination based on race, color, national origin, age, sex, religion, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or disability. The department administers all programs and activities in compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972.If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility, or if you desire further information please write to ADF&G, P.O. Box 25526, Juneau, AK 99802-5526; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 4040N. Fairfield Drive, Suite 300, Arlington, VA 22203; or O.E.O., U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington DC 20240. For information on alternative formats for this and other department publications, please contact the department ADA Coordinator at (voice)907-465-4120, (TDD) 907-465-3646, or (FAX) 907-465-2440. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents....................................................................................................................... i List of Tables ........................................................................................................................... -

Glaciers of the Canadian Rockies

Glaciers of North America— GLACIERS OF CANADA GLACIERS OF THE CANADIAN ROCKIES By C. SIMON L. OMMANNEY SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD Edited by RICHARD S. WILLIAMS, Jr., and JANE G. FERRIGNO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1386–J–1 The Rocky Mountains of Canada include four distinct ranges from the U.S. border to northern British Columbia: Border, Continental, Hart, and Muskwa Ranges. They cover about 170,000 km2, are about 150 km wide, and have an estimated glacierized area of 38,613 km2. Mount Robson, at 3,954 m, is the highest peak. Glaciers range in size from ice fields, with major outlet glaciers, to glacierets. Small mountain-type glaciers in cirques, niches, and ice aprons are scattered throughout the ranges. Ice-cored moraines and rock glaciers are also common CONTENTS Page Abstract ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- J199 Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------- 199 FIGURE 1. Mountain ranges of the southern Rocky Mountains------------ 201 2. Mountain ranges of the northern Rocky Mountains ------------ 202 3. Oblique aerial photograph of Mount Assiniboine, Banff National Park, Rocky Mountains----------------------------- 203 4. Sketch map showing glaciers of the Canadian Rocky Mountains -------------------------------------------- 204 5. Photograph of the Victoria Glacier, Rocky Mountains, Alberta, in August 1973 -------------------------------------- 209 TABLE 1. Named glaciers of the Rocky Mountains cited in the chapter -

S1 Processing of Terminus Positions Many of the Published Sources

S1 Processing of terminus positions Many of the published sources (Table S1) have taken care to account for seasonality in terminus position by, for example, sampling at the same time each year, but we do not think this is a hugely important consideration because the long-term changes we are interested in are far larger than the seasonal variability at a given glacier. When we had to convert terminus 5 traces to terminus position (e.g. for the NSIDC positions) we used the bow method (Bjork et al., 2012). Many glaciers have a terminus position dataset coming from more than one source. In these cases we remove or merge the datasets according to the procedure summarized in Figure S1. Where a dataset has a shorter time period and a lower or similar sampling frequency compared to another dataset, the former dataset is removed. For example, the Carr et al. (2017) and Bunce et al. (2018) datasets are removed in favor of the Cowton et al. (2018) dataset for Helheim glacier (Figure S2). 10 We merge two datasets when a longer record can be made by combining the two. The datasets are merged by calculating an offset during the overlapping period, and then shifting one of the datasets to make a continuous record. The final terminus position record for Helheim thus consists of a merged form of the Andresen et al. (2012), Cowton et al. (2018) and Joughin et al. records (Figure S2). Lastly, glaciers that are known to have a permanent ice shelf/tongue (Petermann, Ryder, 79N), or to surge (Storstrommen) are removed from the dataset.