Trends and Issues in Personal Injury Litigation1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Bar Review Volume 21

THE BAR Volume 21 Number 2 REVIEWJournal of The Bar of Ireland April 2016 Unlawful detention CONTENTS The Bar Review The Bar of Ireland Distillery Building 145-151 Church Street Dublin DO7 WDX8 Direct: +353 (0)1 817 5166 Fax: +353 (0)1 817 5150 Email: [email protected] Web: www.lawlibrary.ie EDITORIAL BOARD 45 Editor Eilis Brennan BL Eileen Barrington SC 66 Gerard Durcan SC Eoghan Fitzsimons SC Niamh Hyland SC Brian Kennedy SC Patrick Leonard SC Paul Anthony McDermott SC Sara Moorhead SC Brian R Murray SC James O'Reilly SC Mary O'Toole SC Mark Sanfey SC 56 Claire Bruton BL Diane Duggan BL Claire Hogan BL Grainne Larkin BL Mark O'Connell BL Thomas O'Malley BL Ciara Murphy, Director Shirley Coulter, Director, Comms and Policy Vanessa Curley, Law Library Deirdre Lambe, Law Library Rose Fisher, PA to the Director Tom Cullen, Publisher Paul O'Grady, Publisher PUBLISHERS Published on behalf of The Bar of Ireland 54 59 48 by Think Media Ltd Editorial: Ann-Marie Hardiman Paul O’Grady Colm Quinn Message from the Chairman 44 Interview 56 Design: Tony Byrne Tom Cullen Moving on Ruth O’Sullivan Editor's note 45 Niamh Short Advertising: Paul O’Grady Law in practice 59 News 45 Commercial matters and news items relating Damages for unlawful judicial jailing 59 to The Bar Review should be addressed to: Launch of Bar of Ireland 1916 exhibition Controlling the market 62 Paul O’Grady Bar of Ireland Transition Year Programme The Bar Review Report from The Bar of Ireland Annual Conference 2016 The Battle of the Four Courts, 1916 66 Think Media Ltd The -

Supreme Court Annual Report 2020

2020Annual Report Report published by the Supreme Court of Ireland with the support of the Courts Service An tSeirbhís Chúirteanna Courts Service Editors: Sarahrose Murphy, Senior Executive Legal Officer to the Chief Justice Patrick Conboy, Executive Legal Officer to the Chief Justice Case summaries prepared by the following Judicial Assistants: Aislinn McCann Seán Beatty Iseult Browne Senan Crawford Orlaith Cross Katie Cundelan Shane Finn Matthew Hanrahan Cormac Hickey Caoimhe Hunter-Blair Ciara McCarthy Rachael O’Byrne Mary O’Rourke Karl O’Reilly © Supreme Court of Ireland 2020 2020 Annual Report Table of Contents Foreword by the Chief Justice 6 Introduction by the Registrar of the Supreme Court 9 2020 at a glance 11 Part 1 About the Supreme Court of Ireland 15 Branches of Government in Ireland 16 Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court 17 Structure of the Courts of Ireland 19 Timeline of key events in the Supreme Court’s history 20 Seat of the Supreme Court 22 The Supreme Court Courtroom 24 Journey of a typical appeal 26 Members of the Supreme Court 30 The Role of the Chief Justice 35 Retirement and Appointments 39 The Constitution of Ireland 41 Depositary for Acts of the Oireachtas 45 Part 2 The Supreme Court in 2020 46 COVID-19 and the response of the Court 47 Remote hearings 47 Practice Direction SC21 48 Application for Leave panels 48 Statement of Case 48 Clarification request 48 Electronic delivery of judgments 49 Sitting in King’s Inns 49 Statistics 50 Applications for Leave to Appeal 50 Categorisation of Applications for Leave to Appeal -

20200214 Paul Loughlin Volume Two 2000 Hrs.Pdf

DEBATING CONTRACEPTION, ABORTION AND DIVORCE IN AN ERA OF CONTROVERSY AND CHANGE: NEW AGENDAS AND RTÉ RADIO AND TELEVISION PROGRAMMES 1968‐2018 VOLUME TWO: APPENDICES Paul Loughlin, M. Phil. (Dub) A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Professor Eunan O’Halpin Contents Appendix One: Methodology. Construction of Base Catalogue ........................................ 3 Catalogue ....................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. BASE PROGRAMME CATALOGUE CONSTRUCTION USING MEDIAWEB ...................................... 148 1.2. EXTRACT - MASTER LIST 3 LAST REVIEWED 22/11/2018. 17:15H ...................................... 149 1.3. EXAMPLES OF MEDIAWEB ENTRIES .................................................................................. 150 1.4. CONSTRUCTION OF A TIMELINE ........................................................................................ 155 1.5. RTÉ TRANSITION TO DIGITISATION ................................................................................... 157 1.6. DETAILS OF METHODOLOGY AS IN THE PREPARATION OF THIS THESIS PRE-DIGITISATION ............. 159 1.7. CITATION ..................................................................................................................... 159 Appendix Two: ‘Abortion Stories’ from the RTÉ DriveTime Series ................................ 166 2.1. ANNA’S STORY ............................................................................................................. -

Tony Heffernan Papers P180 Ucd Archives

TONY HEFFERNAN PAPERS P180 UCD ARCHIVES [email protected] www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2013 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Administrative History iv Archival History v CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and Content vi System of Arrangement viii CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access x Language x Finding Aid x DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note x ALLIED MATERIALS Published Material x iii CONTEXT Administrative History The Tony Heffernan Papers represent his long association with the Workers’ Party, from his appointment as the party’s press officer in July 1982 to his appointment as Assistant Government Press Secretary, as the Democratic Left nominee in the Rainbow Coalition government between 1994 and 1997. The papers provide a significant source for the history of the development of the party and its policies through the comprehensive series of press statements issued over many years. In January 1977 during the annual Sinn Féin Árd Fheis members voted for a name change and the party became known as Sinn Féin the Workers’ Party. A concerted effort was made in the late 1970s to increase the profile and political representation of the party. In 1979 Tomás MacGiolla won a seat in Ballyfermot in the local elections in Dublin. Two years later in 1981 the party saw its first success at national level with the election of Joe Sherlock in Cork East as the party’s first TD. In 1982 Sherlock, Paddy Gallagher and Proinsias de Rossa all won seats in the general election. In 1981 the Árd Fheis voted in favour of another name change to the Workers’ Party. -

Defence Forces Review 2016

Defence Forces Review Defence Forces 2016 Defence Forces Review 2016 Pantone 1545c Pantone 125c Pantone 120c Pantone 468c DF_Special_Brown Pantone 1545c Pantone 2965c Pantone Pantone 5743c Cool Grey 11c Vol 13 Vol Printed by the Defence Forces Printing Press Jn14102 / Sep 2016/ 2300 Defence Forces Review 2016 ISSN 1649 - 7066 Published for the Military Authorities by the Public Relations Branch at the Chief of Staff’s Division, and printed at the Defence Forces Printing Press, Infirmary Road, Dublin 7. © Copyright in accordance with Section 56 of the Copyright Act, 1963, Section 7 of the University of Limerick Act, 1989 and Section 6 of the Dublin University Act, 1989. The material contained in these articles are the views of the authors and do not purport to represent the official views of the Defence Forces. DEFENCE FORCES REVIEW 2016 PREFACE “By academic freedom I understand the right to search for truth and to publish and teach what one holds to be true. This right implies also a duty: one must not conceal any part of what one has recognized to be true. It is evident that any restriction on academic freedom acts in such a way as to hamper the dissemination of knowledge among the people and thereby impedes national judgment and action”. Albert Einstein As Officer in Charge of Defence Forces Public Relations Branch, it gives me great pleasure to be involved in the publication of the Defence Forces Review for 2016. This year’s ‘Review’ continues the tradition of past editions in providing a focus for intellectual debate within the wider Defence Community on matters of professional interest. -

Justice, 2016

05 Justice - Black_Admin 65-1 08/02/2017 15:54 Page 35 Administration, vol. 65, no. 1 (2017), pp. 35–48 doi: 10.1515/admin-2017-0005 Justice, 2016 Lynsey Black Sutherland School of Law, University College Dublin The year opened with the escalation of an ongoing, violent feud on the streets of Dublin. On 5 February a 33-year-old man, David Byrne, was shot dead at a Dublin hotel. On 8 February another man, 59-year-old Eddie Hutch Snr, was shot dead at his home. These killings were the first in a year in which ‘gangland’ crime again became a familiar term in political and media discourse. Following the shootings, the Depart - ment of Justice and Equality sought to offer a ramped-up security presence in Dublin city centre through the establishment of saturation policing, which involved rolling checkpoints and patrols. Measures continued to be introduced throughout the year to adequately resource Gardaí to respond to these threats. In December, for example, a new Garda Armed Support Unit was announced for the Dublin area. Following the upheavals within the Department of Justice and Equality in 2014, the post of secretary general was finally filled in 2016. Noel Waters, who had held the position of acting secretary general since Brian Purcell’s departure in 2014, was appointed to the permanent role. Related to the tumultuous events of 2014 also, the O’Higgins Commission report was released in May. This report dealt with Garda failures in Cavan and Monaghan, which came to light following allegations by Sergeant Maurice McCabe. -

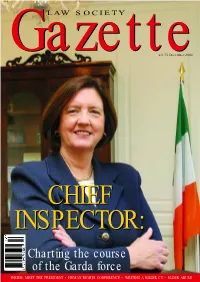

Charting the Course of the Garda Force

LAW SOCIETY GazetteGazette€3.75 December 2008 CHIEFCHIEF INSPECTOR:INSPECTOR: Charting the course of the Garda force INSIDE: MEET THE PRESIDENT • HUMAN RIGHTS CONFERENCE • WRITING A KILLER CV • ELDER ABUSE Specialist legal guidance from the experts BRAND NEW BRAND NEW NEW TITLE Irish Company Employment Law Regulatory Law Secretary’s Handbook General editor: Maeve Regan in Ireland By Jacqueline McGowan-Smyth and Your definitive guide to employment law By Niamh Connery and David Hodnett This practical new book brings together the Eleanor Daly A unique new examination of the knowledge and expertise of Ireland’s leading enforcement and practice of regulatory The very latest company secretarial employment, tax and pension practitioners. law in Ireland procedures and legal guidelines It supplies comprehensive legal information This practical NEW handbook takes you on all aspects of employment and labour law. This new title outlines and examines the through the company secretarial procedures in This includes: regulatory landscape in Ireland including the regulator’s power to prosecute. The use today - the latest Acts and regulations, plus Sources of employment law your practical day to day tasks. Whatever the guidance highlights the powers of authorised The employment relationship situation faced, you’ll find the instructions you officers on a raid or inspection and the rights Pensions and benefits need within the pages of this superb guide. of the persons raided. Employment equality Designed as an everyday manual, Irish You will benefit from easily digestible Termination of employment Company Secretary’s Handbook enables you to: information on the very latest cases and Collective aspects of the employment legislation. -

Annual Report 2015/2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2015/2016 MISSION STATEMENT “To provide leadership and representation on behalf of members of the independent Bar of Ireland, ensure the highest standards of ethical and professional conduct within the profession and to deliver valued and quality services for the benefit of members” CONTENTS Organisation 4 Council of The Bar of Ireland 2015-2016 5 Committees 6 Chairman’s report 8 Director’s report 11 Treasurer’s report 14 Strategic objectives 17 1. Library Services 18 2. Membership Engagement and Benefits 22 3. Promotion, Policy and Public Affairs 26 4. Education and Training 40 5. Regulation 44 Effective operations 46 Finance report 48 Financial accounts 51 3 ORGANISATION Council of The Bar of Ireland Permanent Committees Standing Library Finance Professional Professional External Internal Committee Committee Committee Services Practices Relations Relations Committee Committee Committee Committee Non-Permanent Committees Human Criminal & ADR & LSRA Young Bar Human Rights State Bar Arbitration Circuits Liaison Resources Committee Committee Committee Committee* Committee Committee Committee *Council established a new LSRA Non-Permanent Committee at its meeting in June 2016. 4 COUNCIL 2015-2016 Thomas Creed SC Alice Fawsitt SC Mary Rose Gearty SC Patrick McGrath SC Eanna Mulloy SC Mícheál P. O'Higgins SC David Barniville SC (Chairman) Seamus Woulfe SC Ray Boland BL Seamus Breen BL Claire Hogan BL Grainne Larkin BL Roderick Maguire BL Paul McGarry SC (Vice-Chairman) Tony McGillicuddy BL Imogen McGrath BL Maura McNally BL Elaine -

Launch of Dictionary of Irish Biography, Ireland's Most

www.ucd.ie/ucdtoday reference work reference most Ireland’s authoritative biographical Launch of Dictionary of Irish Biography, SPRING 2010 5. GENOME ZOO 7. IRISH FRANCISCANS 9. ULTRASOUND 15. DESIGN CHALLENGE unravelling the origins gatekeepers of history a window on pregnancy what now for Irish architecture? what’s inside ... President of Ireland Mary McAleese UCD Spin out company, UCD alumnus Brian O’Drioscoll Former President of Ireland, Dr (shown above with Fr Caoimhín Equinome, co-founded by Dr was on hand to launch the UCD Mary Robinson (above) speaks at 7 O’Laoide, Minister Provincial of the 16 Emmeline Hill (above), launches 23 Elite Athlete Academy, the new 24 the Irish in Britain: Conversation Irish Franciscans) views some of the genetic test for ‘speed gene’ in scholarship programme for with the Diaspora forum, at which treasures of the UCD Mícheál Ó thoroughbred horses sports people competing at the she was presented with the Cléirigh collection highest levels inaugural UCD John Hume Medal Handing over the microphone … Parents have views, teachers have views and were given camcorders, training in how to shoot certainly university academics have views on what and edit material, along with a set of guidelines students look for when making their college and and deadlines for submission. The results can be course choices in the CAO system each year. viewed online www.ucdlife.ie Having spent many years managing public When you ask students to film things that might awareness campaigns, marketing campaigns and interest next year’s first years, they inevitably focus media strategies, one valuable lesson always re- on student life. -

Supreme Court of Ireland | Annual Report 2018 Categorisation of Applications for Leave to Appeal

Annual Report Supreme Court of Ireland Supreme Court Cúirt Uachtarach na hÉireann Supreme Court of Ireland Annual Report 2018 Report published by the Supreme Court of Ireland with the support of the Courts Service. Editors: Sarahrose Murphy, Senior Executive Legal Officer to the Chief Justice Patrick Conboy, Executive Legal Officer to the Chief Justice Case summaries prepared by the following Judicial Assistants: Seán Beatty Iseult Browne Paul Carey Patrick Dunne Luke McCann Paul McDonagh Forde Rachael O’Byrne Owen O’Donnell © Supreme Court of Ireland 2019 Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 8 Part 1 | About the Supreme Court of Ireland ............................................................................ 13 Jurisdiction ............................................................................................................................ 14 Background ........................................................................................................................ 14 1. Appellate jurisdiction ..................................................................................................... 14 2. Appellate Constitutional jurisdiction ............................................................................ 15 3. Original jurisdiction ...................................................................................................... -

Friday, May 4Th 2018 Saturday, May 5Th 2018

Law and the Art of the possible: the Fifth Province? Friday, May 4th 2018 A Contemporary & Brehon Perspective 6.45-7.45pm Registration & Reception A plate of food for the traveller 8pm Official launch of the school Introduction by Ellen O’Malley-Dunlop A brief Brehon welcome in Newtown Castle by Fidelma Ó Corráin 8.15pm Opening session Rita Ann Higgins, Author and playwright Saturday, May 5th 2018 7.30am Michael Greene morning walk 9.30am The Brehon perspective: Directed by Ellen O’Malley-Dunlop David Wexler, Director of the International Ellen O’Malley-Dunlop is Chairperson of the National Women’s Council of Network on Therapeutic Jurisprudence Ireland. She has recently completed 6 years as a member of the Board of “Therapeutic jurisprudence: an approach to Gaisce, The President’s Award. She is a member of the Legal Aid Board. law and psychological wellbeing” From 2006-2016, Ellen was CEO of the Dublin Rape Crisis Centre where 10.15am Ó Corráin Memorial lecture she worked with other NGOs and Government agencies to raise awareness Ruairí Ó hUiginn, Professor of Modern Irish, of violence against women in Ireland and lobbied successfully for the NUI Maynooth Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act 2017. 11.15 am Coffee break 11.30 am Session 1 – The criminal justice system in the She is a Psychotherapist and Group Analyst by profession. She was round? appointed Adjunct Professor to the School of Law at the University of Shane Kilcommins, Professor of Law at Limerick in December 2015. She was the first woman Chairperson of the University of Limerick Irish Council for Psychotherapy. -

President Bill Clinton Visits

www.ucd.ie/ucdtoday visits UCD President Bill Clinton WINTER 2010 5. PROTECTING OLDER PEOPLE 7. FREAK WAVES 9. SHARK TALES 13. MONOPOLES Tackling elder abuse in Ireland Harnessing mathematics to Protecting Ireland’s unique species Visualising magnetic events predict ocean currents what’s inside ... New publications in law, theology, The UCD Images of Research UCD spin-out HeyStaks (shown Leinster Senior League Cup Spanish literature and archaeology competition reveals the breadth here) secures €1million equity victory for UCD. 8 (shown here) from UCD authors. 11 and depth of work at the 21 funding to grow their search 23 university. engine business. Characters in conversation The first time I sat in on a “characters in success was such that he was soon invited to asked the manager. “Don’t send her to the bank – conversation” I worried that it would feel like south county parties where they “ate pavlova”. I’ll give you an overdraft to send her to university.” eavesdropping on either a conversation I couldn’t And, while he enjoyed this new sensation, it didn’t And so it was that the young Rosaleen walked in relate to, or a private chat open only to those ‘in convert him and he still spent his summers in to the main hall, straight up to the DramSoc the know’. But, the “characters in conversation” Limerick canvassing for Jim Kemmy. notice board and acted in her first play opposite events run by the team in UCD Alumni Relations While Dungan and Stembridge never managed “the glamorous 3rd year, Des Keogh”. & Fundraising are more like an open facebook wall to bring their conversation into the present, the The next “characters” evening on 9 February for a different generation.