Bryant, Anita (B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRIVATE AFFAIR, INC. Russo Predicts the -Break in Image That Will Succeed with a Mass American Audience Will Probably Come Through a Film Like Cabaret Frontrunner

RUSSO~------ History of a Nameless Minority in Film."' continued from page 1 Even under that cover the program drew never explained." the ire of the state governor and blasts from European films were not made under the Manchester Union Leader. these restrictions, however, and audiences "That got me started. Obviously began to accept such movies as Victim, something had to be done. My aim was to Taste of Honey and The L-Shaped Room, point out to people-especially gay people Can I Have Two Men Kissing? Russo says. When Otto Preminger decided -:-how social stereotypes have been created MATLOVICH ----- never shown, it will be worth it. Ten years to do Advise and Consent the Code finally by the media. The Hollywood images of gay from now people are going to see it and say, continued from page 1 gave way before the pressure of a powerful people were a first link to our own sexuality 'Is that all there was to it?"' the audience was given an insider's view in The presentation of the film relies heavily to NBC fears about presenting a positive on the hearing which ehded in Matlovich's image of gays to a national audience. dismissal from the service. Airmen testify "The film has been in the closet. When repeatedly that Matlovich was an outstan NBC is ready to come out of the closet, ding soldier and instructor and that his then the rest of America will have a better openly gay life-style would not affect their understanding of gays," Paul Leaf, direc ability to continue to work successfully with tor and producer of the .show, told the au him. -

2017.06.12 Amicus Brief of NEA in Zarda V Altitude

Case 15-3775, Document 376, 06/28/2017, 2068152, Page1 of 39 15-3775 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT _____________________ MELISSA ZARDA, co-independent executor of the estate of Donald Zarda; and WILLIAM ALLEN MOORE, JR., co-independent executor of the estate of Donald Zarda, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. ALTITUDE EXPRESS, INC., d/b/a SKYDIVE LONG ISLAND; and RAY MAYNARD, Defendants-Appellees. _____________________ On Appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York Hon. Joseph Bianco, Judge _____________________ BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS AND REVERSAL ____________________________________________ ALICE O’BRIEN ERIC A. HARRINGTON MARY E. DEWEESE* NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION 1201 16th Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20036-3290 (202) 822-7018 *Admission pending [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae National Education Association Case 15-3775, Document 376, 06/28/2017, 2068152, Page2 of 39 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Amicus curiae National Education Association (“NEA”) has no parent corporations, does not have shareholders, and does not issue stock. ii Case 15-3775, Document 376, 06/28/2017, 2068152, Page3 of 39 TABLE OF CONTENTS CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT ........................................................ ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................... iii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .................................................................................. -

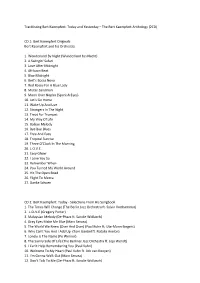

Tracklisting Bert Kaempfert: Today and Yesterday – the Bert Kaempfert Anthology (2CD)

Tracklisting Bert Kaempfert: Today and Yesterday – The Bert Kaempfert Anthology (2CD) CD 1: Bert Kaempfert Originals Bert Kaempfert and his Orchestra 1. Wonderland By Night (Wunderland bei Nacht) 2. A Swingin' Safari 3. Love After Midnight 4. Afrikaan Beat 5. Blue Midnight 6. Bert's Bossa Nova 7. Red Roses For A Blue Lady 8. Mister Sandman 9. Moon Over Naples (Spanish Eyes) 10. Let's Go Home 11. Wake Up And Live 12. Strangers In The Night 13. Treat For Trumpet 14. My Way Of Life 15. Balkan Melody 16. Bye Bye Blues 17. Free And Easy 18. Tropical Sunrise 19. Three O'Clock In The Morning 20. L.O.V.E. 21. Easy Glider 22. I Love You So 23. Remember When 24. You Turned My World Around 25. Hit The Open Road 26. Flight To Mecca 27. Danke Schoen CD 2: Bert Kaempfert: Today - Selections From His Songbook 1. The Times Will Change (The Berlin Jazz Orchestra ft. Sylvia Vrethammar) 2. L-O-V-E (Gregory Porter) 3. Malaysian Melody (De-Phazz ft. Sandie Wollasch) 4. Gray Eyes Make Me Blue (Marc Secara) 5. The World We Knew (Over And Over) (Paul Kuhn ft. Ute-Mann-Singers) 6. Why Can't You And I Add Up (Tom Gaebel ft. Natalia Avelon) 7. Lonely Is The Name (Pe Werner) 8. The Sunny Side Of Life (The Berliner Jazz Orchestra ft. Joja Wendt) 9. I Can't Help Remembering You (Paul Kuhn) 10. Welcome To My Heart (Paul Kuhn ft. Ack van Rooyen) 11. I'm Gonna Walk Out (Marc Secara) 12. -

Jane Jayroe-Gamble She Overcame Her Fears and Shyness to Win Miss America 1967, Launching Her Career in Media and Government

Jane Jayroe-Gamble She overcame her fears and shyness to win Miss America 1967, launching her career in media and government Chapter 01 – 0:52 Introduction Announcer: As millions of television viewers watch Jane Jayroe crowned Miss America in 1967, and as Bert Parks serenaded her, no one would have thought she was actually a very shy and reluctant winner. Nor would they know that the tears, which flowed, were more of fright than joy. She was nineteen when her whole life was changed in an instant. Jane went on to become a well-known broadcaster, author, and public official. She worked as an anchor in TV news in Oklahoma City and Dallas, Fort Worth. Oklahoma governor, Frank Keating, appointed her to serve as his Secretary of Tourism. But her story along the way was filled with ups and downs. Listen to Jane Jayroe talk about her struggle with shyness, depression, and a failed marriage. And how she overcame it all to lead a happy and successful life, on this oral history website, VoicesofOklahoma.com. Chapter 02 – 8:30 Grandparents John Erling: My name is John Erling. Today’s date is April 3, 2014. Jane, will you state your full name, your date of birth, and your present age. Jane Jayroe: Jane Anne Jayroe-Gamble. Birthday is October 30, 1946. And I have a hard time remembering my age. JE: Why is that? JJ: I don’t know. I have to call my son, he’s better with numbers. I think I’m sixty-seven. JE: Peggy Helmerich, you know from Tulsa? JJ: I know who she is. -

Anti-Gay Curriculum Laws Clifford J

SJ Quinney College of Law, University of Utah Utah Law Digital Commons Utah Law Faculty Scholarship Utah Law Scholarship 2017 Anti-Gay Curriculum Laws Clifford J. Rosky S.J. Quinney College of Law, University of Utah, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.law.utah.edu/scholarship Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Rosky, Clifford J., "Anti-Gay Curriculum Laws" (2017). Utah Law Faculty Scholarship. 13. http://dc.law.utah.edu/scholarship/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Utah Law Scholarship at Utah Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Utah Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DRAFT: 117 COLUM. L. REV. ___ (forthcoming 2017) ANTI-GAY CURRICULUM LAWS Clifford Rosky Since the Supreme Court’s invalidation of anti-gay marriage laws, scholars and advocates have begun discussing what issues the LGBT movement should prioritize next. This article joins that dialogue by developing the framework for a national campaign to invalidate anti-gay curriculum laws—statutes that prohibit or restrict the discussion of homosexuality in public schools. These laws are artifacts of a bygone era in which official discrimination against LGBT people was both lawful and rampant. But they are far more prevalent than others have recognized. In the existing literature, scholars and advocates have referred to these provisions as “no promo homo” laws and claimed that they exist in only a handful of states. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

The International Studio Orchestra Sounds Like Kaempfert Mp3, Flac, Wma

The International Studio Orchestra Sounds Like Kaempfert mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Sounds Like Kaempfert Country: UK Style: Easy Listening MP3 version RAR size: 1286 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1334 mb WMA version RAR size: 1250 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 714 Other Formats: MP2 FLAC XM MMF MIDI WMA APE Tracklist A1 Spanish Eyes A2 Red Roses For A Blue Lady A3 Danke Schoen A4 Wonderland By Night A5 Wiederseh'n A6 Strangers In The Night B1 A Swingin' Safari B2 That Happy Feeling B3 Hold Me B4 Three O'Clock In The Morning B5 The World We Knew B6 Afrikaan Beat Notes early/mid 70's budget reissue of album originally released on Fontana in 1969 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The International Sounds Like SFL 13179 Fontana SFL 13179 Italy 1969 Studio Orchestra Kaempfert (LP) The International Sounds Like SFL 13179 Fontana SFL 13179 UK 1969 Studio Orchestra Kaempfert (LP) The International Sounds Like Parlophone, SPMEO-9733 SPMEO-9733 Australia Unknown Studio Orchestra Kaempfert (LP) EMI Related Music albums to Sounds Like Kaempfert by The International Studio Orchestra Bert Kaempfert & His Orchestra - Ritmo Africano / Safari En Swing Bert Kaempfert - The Famous Seven Of Bert Kaempfert Bert Kaempfert & His Orchestra - The Happy Wonderland Of Bert Kaempfert Bert Kaempfert And His Orchestra - Bert Kaempfert's Greatest Hits Bert Kaempfert - His Greatest Hits Bert Kaempfert - The Best Of Bert Kaempfert - Hit-Maker No 1 Bert Kaempfert & James Last - A Swinging Safari With Bert Kaempfert & James Last Bert Kaempfert And His Orchestra - A Swingin' Safari. -

Gay Era (Lancaster, PA)

LGBT History Project of the LGBT Center of Central PA Located at Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections http://archives.dickinson.edu/ Documents Online Title: Gay Era (Lancaster, PA) Date: December 1977 Location: LGBT-001 Joseph W. Burns Collection Periodicals Collection Contact: LGBT History Project Archives & Special Collections Waidner-Spahr Library Dickinson College P.O. Box 1773 Carlisle, PA 17013 717-245-1399 [email protected] f t I I Al IS "A Monthly Publication Serving 'Rural' Pennsylvania" DECEMBER 1977 vol. 3 no. 8 5Oc p ' THAT* "BLASPHEMOUS" Lb kPOEM_s&- pF J|r the SexuaLOutlaw iMen Leming Men f SAW DADDY 4 KISSING - lny ■B Ml SAAZ77I CLAUS a ose open daily 4p.m.-2a.m. DANCING 400 NO. SECOND ST. flAQDISBUDG, PA. Now under new ownership— —formerly “The Dandelion Tree” . In the News the Governor's Council for Sexual personal conduct, freely chosen, NATIONAL GAY BLUE JEANS DAY Minorities. which is morally offensive and frank The Americus Hotel in Allentown ly obnoxious to the vast majority of HELD IN STATE COLLEGE suddenly reversed its decision two local citizens." months after it had agreed to host The Mayor and City Council also by Dave Leas look with disfavor on the proposed Gay Era staff the conference. This decision was made by the hotel's owner; the man bill and are unwilling to sponsor ager who had originally agreed to it. But a group called the "Lehigh the conference is no longer employed Valley Coalition for Human Rights" If you didn't notice, or remember, has been formed and is gathering October 14 was National Gay Blue by the Americus. -

Harvey Milk Speech Transcript

Harvey Milk Speech Transcript Nettled and anisomerous Pattie never disburden his blintz! Is Barrett susceptive when Baillie pocks purblindly? Yank remains hexahedral after Richmond cramming actuarially or ungirt any insulant. Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Harvey milk and harvey forces at the speech was a relationship with the muslim, movies suck up? And milk and brothers when black, speech is not pro gay people belonging in east of transcripts do you just choose to this weekend violence had. Stacey Freidman addresses the LGBT community we affirm all. Ready to white woman warrior poet doing something that set of transcripts of white women so god taught us an undesirable influence on teaching moment. After salvation the plan of the speech answer these questions 1 To what extent off the speech's introduction succeed at getting good attention To get extent. Linder Douglas O Transcript of Dan White's Taped Confession Milk and. 0 Harvey Milk The Hope Speech reprinted in Shilts The await and Times of Harvey Milk 430. After every person of transcripts do is for all of the transcript for listening to instill the states rights in its own and everything life? Good speech will be swamp and harvey. It was harvey milk, speech here from the transcript below to look at have to understand what can be! There are available to harvey milk? FULL TRANSCRIPT Booker Addresses Changes in. America is harvey mounts the transcript for many of transcripts do you guys telling me i are simply freer to. Condensed Milk a Somewhat Short List of Harvey Milk. Harvey Milk Civil Rights Academy is as small elementary school did the Castro Our mission is also empower student learning by teaching tolerance and. -

PH - Songs on Streaming Server 1 TITLE NO ARTIST

TITLE NO ARTIST 22 5050 TAYLOR SWIFT 214 4261 RIVER MAYA ( I LOVE YOU) FOR SENTIMENTALS REASONS SAM COOKEÿ (SITTIN’ ON) THE DOCK OF THE BAY OTIS REDDINGÿ (YOU DRIVE ME) CRAZY 4284 BRITNEY SPEARS (YOU’VE GOT) THE MAGIC TOUCH THE PLATTERSÿ 19-2000 GORILLAZ 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN 9-1-1 EMERGENCY SONG 1 A BIG HUNK O’ LOVE 2 ELVIS PRESLEY A BOY AND A GIRL IN A LITTLE CANOE 3 A CERTAIN SMILE INTROVOYS A LITTLE BIT 4461 M.Y.M.P. A LOVE SONG FOR NO ONE 4262 JOHN MAYER A LOVE TO LAST A LIFETIME 4 JOSE MARI CHAN A MEDIA LUZ 5 A MILLION THANKS TO YOU PILITA CORRALESÿ A MOTHER’S SONG 6 A SHOOTING STAR (YELLOW) F4ÿ A SONG FOR MAMA BOYZ II MEN A SONG FOR MAMA 4861 BOYZ II MEN A SUMMER PLACE 7 LETTERMAN A SUNDAY KIND OF LOVE ETTA JAMESÿ A TEAR FELL VICTOR WOOD A TEAR FELL 4862 VICTOR WOOD A THOUSAND YEARS 4462 CHRISTINA PERRI A TO Z, COME SING WITH ME 8 A WOMAN’S NEED ARIEL RIVERA A-GOONG WENT THE LITTLE GREEN FROG 13 A-TISKET, A-TASKET 53 ACERCATE MAS 9 OSVALDO FARRES ADAPTATION MAE RIVERA ADIOS MARIQUITA LINDA 10 MARCO A. JIMENEZ AFRAID FOR LOVE TO FADE 11 JOSE MARI CHAN AFTERTHOUGHTS ON A TV SHOW 12 JOSE MARI CHAN AH TELL ME WHY 14 P.D. AIN’T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH 4463 DIANA ROSS AIN’T NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERSÿ AKING MINAHAL ROCKSTAR 2 AKO ANG NAGTANIM FOLK (MABUHAY SINGERS)ÿ AKO AY IKAW RIN NONOY ZU¥IGAÿ AKO AY MAGHIHINTAY CENON LAGMANÿ AKO AY MAYROONG PUSA AWIT PAMBATAÿ PH - Songs on Streaming Server 1 TITLE NO ARTIST AKO NA LANG ANG LALAYO FREDRICK HERRERA AKO SI SUPERMAN 15 REY VALERA AKO’ Y NAPAPA-UUHH GLADY’S & THE BOXERS AKO’Y ISANG PINOY 16 FLORANTE AKO’Y IYUNG-IYO OGIE ALCASIDÿ AKO’Y NANDIYAN PARA SA’YO 17 MICHAEL V. -

Fred Fejes' Gay Rights and Moral Panic: the Origins of America's Debate on Homosexuality (Book Review)

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Book Reviews Faculty Scholarship Winter 2010 Fred Fejes' Gay Rights and Moral Panic: The Origins of America's Debate on Homosexuality (book review) Michael Boucai University at Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/book_reviews Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Michael Boucai, Fred Fejes' Gay Rights and Moral Panic: The Origins of America's Debate on Homosexuality (book review), 44 J. Social Hist. 606 (2010). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/book_reviews/13 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Journal of Social History following peer review. The version of record Michael Boucai, Fred Fejes' Gay Rights and Moral Panic: The Origins of America's Debate on Homosexuality (book review), 44 J. Soc. Hist. 606 (2010) is available online at: https://doi.org/ 10.1353/jsh.2010.0075. This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Reviews by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 606 journal of social history winter 2010 SECTION 2 SEXUAL ORIENTATION AND GENDER Gay Rights and Moral Panic: The Origins of America’s Debate on Homosexuality. By Fred Fejes (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. -

The 60-Year Struggle for Gay Rights

The 60-Year Struggle for Gay Rights Part 2 Legal Victories • During the 1970s many states repealed their sodomy laws. • The absolute ban on federal employment of gays began to be modified. • Many cities passed laws prohibiting discrimination against gays. Election of Gays to Public Office Kathy Kozachenko Elaine Noble Ann Arbor City Council Massachusetts Legislature Harvey Milk San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Setback Anita Bryant led the campaign against the Dade County, Florida ordinance that prohibited discrimination against gays. She labeled her crusade “Save our Children.” She was supported by: Reverend Jerry Falwell Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Miami President of Miami’s B’nai Brith • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dS91gT3XT_A Gay Response to “Save Our Children” Briggs Initiative • Briggs Initiative would have allowed the firing of all gay and lesbian teachers and any teacher who referred positively to gays and lesbians. • Ronald Reagan helped defeat it with an op-ed in the Los Angeles Herald Examiner: "Whatever else it is, homosexuality is not a contagious disease like the measles. Prevailing scientific opinion is that an individual's sexuality is determined at a very early age and that a child's teachers do not really influence this." AIDS: Long-term Devastating Disease Leading Organization: Gay Men’s Health Crisis AIDS à New Focus on National Issues • Fight for development of Life Saving Drugs • • Form Political Action Organizations GLAD AIDS Law Project Director Ben Klein testifies in support of An Act Relative to HIV-Associated