6 Toward Centre Stage 1933-1949

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Four Courts of Sir Lyman Duff

THE FOUR COURTS OF SIR LYMAN DUFF RICHARD GOSSE* Vancouver I. Introduction. Sir Lyman Poore Duff is the dominating figure in the Supreme Court of Canada's first hundred years. He sat on the court for more than one-third of those years, in the middle period, from 1906 to 1944, participating in nearly 2,000 judgments-and throughout that tenure he was commonly regarded as the court's most able judge. Appointed at forty-one, Duff has been the youngest person ever to have been elevated to the court. Twice his appointment was extended by special Acts of Parliament beyond the mandatory retirement age of seventy-five, a recogni- tion never accorded to any other Canadian judge. From 1933, he sat as Chief Justice, having twice previously-in 1918 and 1924 - almost succeeded to that post, although on those occasions he was not the senior judge. During World War 1, when Borden considered resigning over the conscription issue and recommending to the Governor General that an impartial national figure be called upon to form a government, the person foremost in his mind was Duff, although Sir Lyman had never been elected to public office. After Borden had found that he had the support to continue himself, Duff was invited to join the Cabinet but declined. Mackenzie King con- sidered recommending Duff for appointment as the first Canadian Governor General. Duff undertook several inquiries of national interest for the federal government, of particular significance being the 1931-32 Royal Commission on Transportation, of which he was chairman, and the 1942 investigation into the sending of Canadian troops to Hong Kong, in which he was the sole commissioner . -

Special Series on the Federal Dimensions of Reforming the Supreme Court of Canada

SPECIAL SERIES ON THE FEDERAL DIMENSIONS OF REFORMING THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA The Supreme Court of Canada: A Chronology of Change Jonathan Aiello Institute of Intergovernmental Relations School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University SC Working Paper 2011 21 May 1869 Intent on there being a final court of appeal in Canada following the Bill for creation of a Supreme country’s inception in 1867, John A. Macdonald, along with Court is withdrawn statesmen Télesphore Fournier, Alexander Mackenzie and Edward Blake propose a bill to establish the Supreme Court of Canada. However, the bill is withdrawn due to staunch support for the existing system under which disappointed litigants could appeal the decisions of Canadian courts to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) sitting in London. 18 March 1870 A second attempt at establishing a final court of appeal is again Second bill for creation of a thwarted by traditionalists and Conservative members of Parliament Supreme Court is withdrawn from Quebec, although this time the bill passed first reading in the House. 8 April 1875 The third attempt is successful, thanks largely to the efforts of the Third bill for creation of a same leaders - John A. Macdonald, Télesphore Fournier, Alexander Supreme Court passes Mackenzie and Edward Blake. Governor General Sir O’Grady Haly gives the Supreme Court Act royal assent on September 17th. 30 September 1875 The Honourable William Johnstone Ritchie, Samuel Henry Strong, The first five puisne justices Jean-Thomas Taschereau, Télesphore Fournier, and William are appointed to the Court Alexander Henry are appointed puisne judges to the Supreme Court of Canada. -

Canadian Law Library Review Revue Canadienne Des Bibliothèques Is Published By: De Droit Est Publiée Par

CANADIAN LAW LIBRARY REVIEW REVUE CANADIENNE DES BIBLIOTHÈQUES DE DROIT 2017 CanLIIDocs 227 VOLUME/TOME 42 (2017) No. 2 APA Journals® Give Your Users the Psychological Research They Need LEADING JOURNALS IN LAW AND PSYCHOLOGY 2017 CanLIIDocs 227 Law and Human Behavior® Official Journal of APA Division 41 (American Psychology-Law Society) Bimonthly • ISSN 0147-7307 2.884 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.542 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychological Assessment® Monthly • ISSN 1040-3590 3.806 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.901 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychology, Public Policy, and Law® Quarterly • ISSN 1076-8971 2.612 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 1.986 2015 Impact Factor®* Journal of Threat Assessment and Management® Official Journal of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, the Association of European Threat Assessment Professionals, the Canadian Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, and the Asia Pacific Association of Threat Assessment Professionals Quarterly • ISSN 2169-4842 * ©Thomson Reuters, Journal Citation Reports® for 2015 ENHANCE YOUR PSYCHOLOGY SERIALS COLLECTION To Order Journal Subscriptions, Contact Your Preferred Subscription Agent American Psychological Association | 750 First Street, NE | Washington, DC 20002-4242 USA ‖‖ CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE 5 From the Editor The Law of Declaratory Judgments 40 De la rédactrice Reviewed by Melanie R. Bueckert 7 President’s Message Pocket Ontario OH&S Guide to Violence and 41 Le mot de la présidente Harassment Reviewed by Megan Siu 9 Featured Articles Articles de fond Power of Persuasion: Essays -

Canadian Law Library Review Revue Canadienne Des Bibliothèques Is Published By: De Droit Est Publiée Par

CANADIAN LAW LIBRARY REVIEW REVUE CANADIENNE DES BIBLIOTHÈQUES DE DROIT VOLUME/TOME 42 (2017) No. 2 APA Journals® Give Your Users the Psychological Research They Need LEADING JOURNALS IN LAW AND PSYCHOLOGY Law and Human Behavior® Official Journal of APA Division 41 (American Psychology-Law Society) Bimonthly • ISSN 0147-7307 2.884 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.542 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychological Assessment® Monthly • ISSN 1040-3590 3.806 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 2.901 2015 Impact Factor®* Psychology, Public Policy, and Law® Quarterly • ISSN 1076-8971 2.612 5-Year Impact Factor®* | 1.986 2015 Impact Factor®* Journal of Threat Assessment and Management® Official Journal of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, the Association of European Threat Assessment Professionals, the Canadian Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, and the Asia Pacific Association of Threat Assessment Professionals Quarterly • ISSN 2169-4842 * ©Thomson Reuters, Journal Citation Reports® for 2015 ENHANCE YOUR PSYCHOLOGY SERIALS COLLECTION To Order Journal Subscriptions, Contact Your Preferred Subscription Agent American Psychological Association | 750 First Street, NE | Washington, DC 20002-4242 USA ‖‖ CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE 5 From the Editor The Law of Declaratory Judgments 40 De la rédactrice Reviewed by Melanie R. Bueckert 7 President’s Message Pocket Ontario OH&S Guide to Violence and 41 Le mot de la présidente Harassment Reviewed by Megan Siu 9 Featured Articles Articles de fond Power of Persuasion: Essays by a Very Public 41 Edited by John -

1050 the ANNUAL REGISTER Or the Immediate Vicinity. Hon. E. M. W

1050 THE ANNUAL REGISTER or the immediate vicinity. Hon. E. M. W. McDougall, a Puisne Judge of the Superior Court for the Province of Quebec: to be Puisne Judge of the Court of King's Bench in and for the Province of Quebec, with residence at Montreal or the immediate vicinity. Pierre Emdle Cote, K.C., New Carlisle, Que.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Superior Court in and for the Province of Quebec, effective Oct. 1942, with residence at Quebec or the immediate vicinity. Dec. 15, Henry Irving Bird, Vancouver, B.C.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of British Columbia, with residence at Vancouver, or the immediate vicinity. Frederick H. Barlow, Toronto, Ont., Master of the Supreme Court of Ontario: to be a Judge of the High Court of Justice for Ontario. Roy L. Kellock, K.C., Toronto, Ont.: to be a Justice of the Court of Appeal for Ontario and ex officio a Judge of the High Court of Juscico for Ontario. 1943. Feb. 4, Robert E. Laidlaw, K.C., Toronto, Ont.: to be a Justice of the Court of Appeal for Ontario and ex officio a Judge of the High Court of Justice for Ontario. Apr. 22, Hon. Thane Alexander Campbell, K.C., Summer- side, P.E.I.: to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature of P.E.I. Ivan Cleveland Rand, K.C., Moncton, N.B.: to be a Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Canada. July 5, Hon. Justice Harold Bruce Robertson, a Judge of the Supreme Court of British Columbia: to be a Justice of Appeal of the Court of Appeal for British Columbia. -

A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962

8 A Decade of Adjustment 1950-1962 When the newly paramount Supreme Court of Canada met for the first timeearlyin 1950,nothing marked theoccasionasspecial. ltwastypicalof much of the institution's history and reflective of its continuing subsidiary status that the event would be allowed to pass without formal recogni- tion. Chief Justice Rinfret had hoped to draw public attention to the Court'snew position throughanotherformalopeningofthebuilding, ora reception, or a dinner. But the government claimed that it could find no funds to cover the expenses; after discussing the matter, the cabinet decided not to ask Parliament for the money because it might give rise to a controversial debate over the Court. Justice Kerwin reported, 'They [the cabinet ministers] decided that they could not ask fora vote in Parliament in theestimates tocoversuchexpensesas they wereafraid that that would give rise to many difficulties, and possibly some unpleasantness." The considerable attention paid to the Supreme Court over the previous few years and the changes in its structure had opened broader debate on aspects of the Court than the federal government was willing to tolerate. The government accordingly avoided making the Court a subject of special attention, even on theimportant occasion of itsindependence. As a result, the Court reverted to a less prominent position in Ottawa, and the status quo ante was confirmed. But the desire to avoid debate about the Court discouraged the possibility of change (and potentially of improvement). The St Laurent and Diefenbaker appointments during the first decade A Decade of Adjustment 197 following termination of appeals showed no apparent recognition of the Court’s new status. -

Review of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical

A JUDICIAL LOUDMOUTH WITH A QUIET LEGACY: A REVIEW OF EMMETT HALL: ESTABLISHMENT RADICAL DARCY L. MACPHERSON* n the revised and updated version of Emmett Hall: Establishment Radical, 1 journalist Dennis Gruending paints a compelling portrait of a man whose life’s work may not be directly known by today’s younger generation. But I Gruending makes the point quite convincingly that, without Emmett Hall, some of the most basic rights many of us cherish might very well not exist, or would exist in a form quite different from that on which Canadians have come to rely. The original version of the book was published in 1985, that is, just after the patriation of the Canadian Constitution, and the entrenchment of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,2 only three years earlier. By 1985, cases under the Charter had just begun to percolate up to the Supreme Court of Canada, a court on which Justice Hall served for over a decade, beginning with his appointment in late 1962. The later edition was published two decades later (and ten years after the death of its subject), ostensibly because events in which Justice Hall had a significant role (including the Canadian medicare system, the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Stephen Truscott, and claims of Aboriginal title to land in British Columbia) still had currency and relevance in contemporary Canadian society. Despite some areas where the new edition may be considered to fall short which I will mention in due course, this book was a tremendous read, both for those with legal training, and, I suspect, for those without such training as well. -

REGISTER of OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS 1165 Hon. J

REGISTER OF OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS 1165 Hon. J. Watson MacNaught: to be a member of the Administration. Hon. Roger Teillet: to be Minister of Veterans Affairs. Hon. Judy LaMarsh: to be Minister of National Health and Welfare. Hon. Charles Mills Drury: to be Minister of Defence Production. Hon. Guy Favreau: to be Minister of Citizenship and Immigration. Hon. John Robert Nichol son: to be Minister of Forestry. Hon. Harry Hays: to be Minister of Agriculture. Hon. Rene" Tremblay: to be a member of the Administration. May 23, Hon. Robert Gordon Robertson: to be Secretary to the Cabinet, from July 1, 1963. July 25, Hon. Charles Mills Drury: to be Minister of Industry. Aug. 14, Hon. Maurice Lamontagne: to act as the Minister for the purposes of the Economic Council of Canada Act. Senate Appointments.—1962. Sept. 24, Hon. George Stanley White, a member of the Senate: to be Speaker of the Senate. M. Grattan O'Leary, Ottawa, Ont.: to be a Senator for the Province of Ontario. Edgar Fournier, Iroquois, N.B.: to be a Senator for the Province of New Brunswick. Allister Grosart, Ottawa, Ont.: to be a Senator for the Province of Ontario. Sept. 25, Frank Welch, Wolfville, N.S.: to be a Senator for the Province of Nova Scotia. Clement O'Leary, Antigonish, N.S.: to be a Senator for the Province of Nova Scotia. Nov. 13, Jacques Flynn, Quebec, Que.: to be a Senator for the Province of Quebec. Nov. 29, John Alexander Robertson, Kenora, Ont.: to be a Senator for the Province of Ontario. 1963. Feb. -

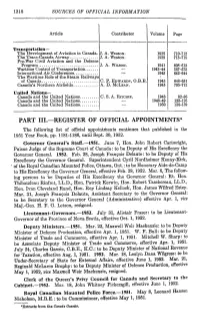

PART III.—REGISTER of OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS* the Following List of Official Appointments Continues That Published in the 1951 Year Book, Pp

1218 SOURCES OF OFFICIAL INFORMATION Article Contributor Volume Page Transportation— The Development of Aviation in Canada. J. A. WILSON. 1938 710-712 The Trans-Canada Airway J. A. WILSON. 1938 713-715 Pre-War Civil Aviation and the Defence Program J. A. WILSON. 1941 608-612 Wartime Control of Transportation 1943-14 567-575 International Air Conferences 1945 642-644 The Wartime Role of the Steam Railways of Canada C. P. EDWARDS, O.B.E. 1945 648-651 Canada's Northern Airfields A. D. MCLEAN. 1945 705-712 United Nations- Canada and the United Nations C. S. A. RITCHIE. 1946 82-86 Canada and the United Nations 1948-49 122-125 Canada and the United Nations 1950 134-139 PART III.—REGISTER OF OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS* The following list of official appointments continues that published in the 1951 Year Book, pp. 1181-1186, until Sept. 30, 1952. Governor General's Staff.—1951. June 7, Hon. John Robert Cartwright, Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Canada: to be Deputy of His Excellency the Governor General. 1952. Feb. 28, Joseph Francois Delaute: to be Deputy of His Excellency the Governor General. Superintendent Cyril Nordheimer Kenny-Kirk, of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Ottawa, Ont.: to be Honorary Aide-de-Camp to His Excellency the Governor General, effective Feb. 28, 1952. Mar. 6, The follow ing persons to be Deputies of His Excellency the Governor General: Rt. Hon. Thibaudeau Rinfret, LL.D., Hon. Patrick Kerwin, Hon. Robert Taschereau, LL.D., Hon. Ivan Cleveland Rand, Hon. Roy Lindsay Kellock, Hon. James Wilfred Estey. Mar. -

Historical Portraits Book

HH Beechwood is proud to be The National Cemetery of Canada and a National Historic Site Life Celebrations ♦ Memorial Services ♦ Funerals ♦ Catered Receptions ♦ Cremations ♦ Urn & Casket Burials ♦ Monuments Beechwood operates on a not-for-profit basis and is not publicly funded. It is unique within the Ottawa community. In choosing Beechwood, many people take comfort in knowing that all funds are used for the maintenance, en- hancement and preservation of this National Historic Site. www.beechwoodottawa.ca 2017- v6 Published by Beechwood, Funeral, Cemetery & Cremation Services Ottawa, ON For all information requests please contact Beechwood, Funeral, Cemetery and Cremation Services 280 Beechwood Avenue, Ottawa ON K1L8A6 24 HOUR ASSISTANCE 613-741-9530 • Toll Free 866-990-9530 • FAX 613-741-8584 [email protected] The contents of this book may be used with the written permission of Beechwood, Funeral, Cemetery & Cremation Services www.beechwoodottawa.ca Owned by The Beechwood Cemetery Foundation and operated by The Beechwood Cemetery Company eechwood, established in 1873, is recognized as one of the most beautiful and historic cemeteries in Canada. It is the final resting place for over 75,000 Canadians from all walks of life, including im- portant politicians such as Governor General Ramon Hnatyshyn and Prime Minister Sir Robert Bor- den, Canadian Forces Veterans, War Dead, RCMP members and everyday Canadian heroes: our families and our loved ones. In late 1980s, Beechwood began producing a small booklet containing brief profiles for several dozen of the more significant and well-known individuals buried here. Since then, the cemetery has grown in national significance and importance, first by becoming the home of the National Military Cemetery of the Canadian Forces in 2001, being recognized as a National Historic Site in 2002 and finally by becoming the home of the RCMP National Memorial Cemetery in 2004. -

Ian Bushnell*

JUstice ivan rand and the roLe of a JUdge in the nation’s highest coUrt Ian Bushnell* INTRODUCTION What is the proper role for the judiciary in the governance of a country? This must be the most fundamental question when the work of judges is examined. It is a constitutional question. Naturally, the judicial role or, more specifically, the method of judicial decision-making, critically affects how lawyers function before the courts, i.e., what should be the content of the legal argument? What facts are needed? At an even more basic level, it affects the education that lawyers should experience. The present focus of attention is Ivan Cleveland Rand, a justice of the Supreme Court of Canada from 1943 until 1959 and widely reputed to be one of the greatest judges on that Court. His reputation is generally based on his method of decision-making, a method said to have been missing in the work of other judges of his time. The Rand legal method, based on his view of the judicial function, placed him in illustrious company. His work exemplified the traditional common law approach as seen in the works of classic writers and judges such as Sir Edward Coke, Sir Matthew Hale, Sir William Blackstone, and Lord Mansfield. And he was in company with modern jurists whose names command respect, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and Benjamin Cardozo, as well as a law professor of Rand at Harvard, Roscoe Pound. In his judicial decisions, addresses and other writings, he kept no secrets about his approach and his view of the judicial role. -

The Supremecourt History Of

The SupremeCourt of Canada History of the Institution JAMES G. SNELL and FREDERICK VAUGHAN The Osgoode Society 0 The Osgoode Society 1985 Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-34179 (cloth) Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Snell, James G. The Supreme Court of Canada lncludes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-802@34179 (bound). - ISBN 08020-3418-7 (pbk.) 1. Canada. Supreme Court - History. I. Vaughan, Frederick. 11. Osgoode Society. 111. Title. ~~8244.5661985 347.71'035 C85-398533-1 Picture credits: all pictures are from the Supreme Court photographic collection except the following: Duff - private collection of David R. Williams, Q.c.;Rand - Public Archives of Canada PA@~I; Laskin - Gilbert Studios, Toronto; Dickson - Michael Bedford, Ottawa. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Social Science Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA History of the Institution Unknown and uncelebrated by the public, overshadowed and frequently overruled by the Privy Council, the Supreme Court of Canada before 1949 occupied a rather humble place in Canadian jurisprudence as an intermediate court of appeal. Today its name more accurately reflects its function: it is the court of ultimate appeal and the arbiter of Canada's constitutionalquestions. Appointment to its bench is the highest achieve- ment to which a member of the legal profession can aspire. This history traces the development of the Supreme Court of Canada from its establishment in the earliest days following Confederation, through itsattainment of independence from the Judicial Committeeof the Privy Council in 1949, to the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982.