John Hancock By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Federal Constitution and Massachusetts Ratification : A

, 11l""t,... \e ,--.· ', Ir \" ,:> � c.'�. ,., Go'.l[f"r•r•r-,,y 'i!i • h,. I. ,...,,"'P�r"'T'" ""J> \S'o ·� � C ..., ,' l v'I THE FEDERAL CONSTlTUTlON \\j\'\ .. '-1',. ANV /JASSACHUSETTS RATlFlCATlON \\r,-,\\5v -------------------------------------- . > .i . JUN 9 � 1988 V) \'\..J•, ''"'•• . ,-· �. J ,,.._..)i.�v\,\ ·::- (;J)''J -�·. '-,;I\ . � '" - V'-'� -- - V) A TEACHING KIT PREPAREV BY � -r THE COIJMOMVEALTH M,(SEUM ANV THE /JASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES AT COLUM.BIA POINf ]') � ' I � Re6outee Matetial6 6ot Edueatot6 and {I · -f\ 066ieial& 6ot the Bieentennial 06 the v-1 U.S. Con&titution, with an empha6i& on Ma&&aehu&ett6 Rati6ieation, eontaining: -- *Ma66aehu6ett& Timeline *Atehival Voeument6 on Ma&&aehu&ett& Rati6ieation Convention 1. Govetnot Haneoek'6 Me&6age. �����4Y:t4���� 2. Genetal Coutt Re6olve& te C.U-- · .....1. *. Choo6ing Velegate& 6ot I\) Rati6ieation Convention. 0- 0) 3. Town6 &end Velegate Name&. 0) C 4. Li6t 06 Velegate& by County. CJ) 0 CJ> c.u-- l> S. Haneoek Eleeted Pte6ident. --..J s:: 6. Lettet 6tom Elbtidge Getty. � _:r 7. Chatge6 06 Velegate Btibety. --..J C/)::0 . ' & & • o- 8 Hane oe k Pt op o 6e d Amen dme nt CX) - -j � 9. Final Vote on Con&titution --- and Ptopo6ed Amenwnent6. Published by the --..J-=--- * *Clue6 to Loeal Hi&toty Officeof the Massachusetts Secretary of State *Teaehing Matetial6 Michaelj, Connolly, Secretary 9/17/87 < COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS !f1Rl!j OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE CONSTITUTtON Michael J. Connolly, Secretary The Commonwealth Museum and the Massachusetts Columbia Point RATIFICATION OF THE U.S. CONSTITUTION MASSACHUSETTS TIME LINE 1778 Constitution establishing the "State of �assachusetts Bay" is overwhelmingly rejected by the voters, in part because it lacks a bill of rights. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JUNE 6, 2017 No. 96 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was securing the beachhead. The countless Finally, in March 2016, after 64 years called to order by the Speaker pro tem- heroes who stormed the beaches of Nor- and extensive recovery efforts, Staff pore (Mr. BERGMAN). mandy on that fateful day 73 years ago Sergeant Van Fossen’s remains were f will never be forgotten. confirmed found and returned to his I had the honor of visiting this hal- home in Heber Springs, Arkansas. DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO lowed ground over Memorial Day, and I would like to extend my deepest TEMPORE while I was paying tribute to the brave condolences to the family of Staff Ser- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- soldiers who made the ultimate sac- geant Van Fossen and hope that they fore the House the following commu- rifice at the Normandy American Cem- are now able to find peace that he is fi- nication from the Speaker: etery and Memorial, an older French- nally home and in his final resting man by the name of Mr. Vonclair ap- place. WASHINGTON, DC, proached me simply wanting to honor June 6, 2017. CONWAY BIKESHARE PROGRAM I hereby appoint the Honorable JACK his liberators. He said that he just Mr. HILL. Mr. Speaker, last month BERGMAN to act as Speaker pro tempore on wanted to thank an American. -

2012 NHBB Set C Round #9

2012 NHBB Set C Bowl Round 9 First Quarter BOWL ROUND 9 1. This owner of Buckland Abbey served as the mayor of Plymouth, England and procured a water supply of 300 years for that city. He claimed that he singed the beard of a foreign monarch following his raid on the port of Cadiz, and legend states that he calmly resumed bowling after viewing the Spanish Armada off the coast of England. For 10 points, name this English seadog who circumnavigated the globe in his ship The Golden Hind. ANSWER: Sir Francis Drake 030-12-64-09101 2. This man described a scene involving a sick woman and an unclean syringe in a section titled "Irma's injection." This man came up with the term libido and described the structure of the psyche as being made up of the ego, superego, and id. For 10 points, name this Austrian who wrote The Interpretation of Dreams and founded psychoanalysis. ANSWER: Sigmund Freud 023-12-64-09102 3. The chancres (CAIN-kerz) caused by this disease were originally treated with mercury, though Salvarsan replaced it in the 1900s. In the 1940s in Guatemala, and earlier at the Tuskeegee Institute, unethical clinical studies were carried out on patients with this disease. For 10 points, name this venereal disease that causes dementia, which was brought from the Americas to Europe by Christopher Columbus. ANSWER: syphilis 133-12-64-09103 4. This woman’s rule was the target of the Kosciuszko rebellion in Poland. She was also the target of Pugachev's rebellion, led by a man claiming to be her late husband, Peter III, whom she had conspired to depose and kill. -

The Citizen's Almanac

M-76 (rev. 09/14) n 1876, to commemorate 100 years of independence from Great Britain, Archibald M. Willard presented his painting, Spirit of ‘76, Iat the U.S. Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, PA. The painting depicts three generations of Americans fighting for their new nation’s freedom, one of whom is marching along though slightly wounded in battle. Willard’s powerful portrayal of the strength and determination of the American people in the face of overwhelming odds inspired millions. The painting quickly became one of the most popular patriotic images in American history. This depiction of courage and character still resonates today as the Spirit of ‘76 lives on in our newest Americans. “Spirit of ‘76” (1876) by Archibald M. Willard. Courtesy of the National Archives, NARA File # 148-GW-1209 The Citizen’s Almanac FUNDAMENTAL DOCUMENTS, SYMBOLS, AND ANTHEMS OF THE UNITED STATES U.S. GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE Use of ISBN This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. Use of the ISBN 978-0-16-078003-5 is for U.S. Government Printing Office Official Editions only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. The information presented in The Citizen’s Almanac is considered public information and may be distributed or copied without alteration unless otherwise specified. The citation should be: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Office of Citizenship, The Citizen’s Almanac, Washington, DC, 2014. -

The First Battles of the American Revolution Took Place

Lesson 6: Closer to War The Intolerable Acts were passed. Representatives from the Colonies met to protest the Intolerable Acts. First Continental Congress 1774 Theme of the First Continental Congress Textbook Activity Alternate Text Activity The Intolerable Acts were passed. The meeting was called the Plans for a boycott First Continental were made. Congress. Representatives from the Colonies met to protest the Intolerable Acts. A Declaration of A Continental Rights was Association was written. It included formed to enforce a list of grievances the boycott. Resolution Resolved, That they are entitled to life, liberty and property: and they have never [given up] . a right to dispose of either without their consent. Resolved, That the foundation of English liberty, and of all free government, is a right in the people to participate in their legislative council:… Resolved, That they have a right peaceably to assemble, consider of their grievances, and petition the king; and that all prosecutions, prohibitory proclamations, and commitments for the same, are illegal. Keeping track of Political Ideas Declaration of Resolves 1st Amendment Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. Writing Plan for First Continental Congress Simulation Your Task: Pretend you are a representative at the First Continental Congress. Write -

The Faulkner Murals: Depicting the Creation of a Nation

DEPICTING the CREATION of a NATION The Story Behind the Murals About Our Founding Documents by LESTER S. GORELIC wo large oil-on-canvas murals (each about 14 feet by 37.5 feet) decorate the walls of the Rotunda of the National T Archives in Washington, D.C. The murals depict pivotal moments in American history represented by two founding doc uments: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. In one mural, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia is depicted handing over his careful ly worded and carefully edited draft of the Declaration of Independence to John Hancock of Massachusetts. Many of the other Founding Fathers look on, some fully supportive, some apprehensive. In the other, James Madison of Virginia is depicted presenting his draft of the Constitution to fellow Virginian George Washington, president of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, and to other members of the Convention. Although these moments occurred in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia (Independence Hall)—not in the sylvan settings shown in the murals—the two price less documents are now in the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., and have been seen by millions of visitors over the years. When the National Archives Building was built in the Jefferson’s placement at the front of the Committee of mid-1930s, however, these two founding documents were Five reflects his position as its head. Although Jefferson was in the custody of the Library of Congress and would not the primary author of the Declaration, his initial draft was be transferred to the Archives until 1952. Even so, the ar edited first by Adams and then by Franklin. -

In Other Words, It Will Get More Americans to Join Them. Confederation

Binder Page _____ Name ________________________________________________________ Period ________ Video- Liberty’s Kids: “The First Fourth of July” Date ___________________ 1. Why does George Washington believe that they need an official Declaration of Independence? It will gain more “popular support.” In other words, it will get more Americans to join them. 2. Where do Hessians come from? Germany 3. What word does James use to describe the people who catch them? Tories (“Watch out, Henri! They’re Tories!”) 4. Richard Henry Lee of Virginia wants the Second Continental Congress to vote on three resolutions: 1. That the colonies are in fact Free and Independent states, and absolved of all allegiance to Great Britain. 2. That the independent states seek to form foreign Alliances (like with France, for example) 3. That the independent states establish a plan of confederation (to make a new government) What does Sarah think of Lee’s resolutions? They are “treason.” In other words, he is a traitor to his king and country. 5. What does Mr. John Dickinson think of Independence? Why? It is dangerous and impossible. Dangerous, because the Indians on the frontier will start killing people and maybe another country will take us over without the protection of Britain; Impossible, because the middle colonies (New York and Pennsylvania) do not support it. 6. Who gets chosen to write the Declaration? Thomas Jefferson 7. Who are the group that get a ride from James and Sarah? The New Jersey delegation (who are just elected and have come to vote for independence. Where is Caesar Rodney of Delaware? Why was he not at the meeting of Congress? He is deathly ill and at his home in Delaware. -

MASSACHUSETTS BAY. by the Governor

MASSACHUSETTS BAY. By the Governor. — A Proclamation For the encouragement of Piety and Virtue In humble imitation of our most gracious Sovereign, George the Third, I, by and with the advice of his Majesty's Council, publish this Order and Proclamation, exhorting his Majesty's subjects to avoid all Hypocrisy, Sedition, Licentiousness, and other immoralities, and to adopt a grateful sense of obedience and duty to God and to Country. Good people, the infringements being committed upon the sacred rights of the crown and people of Great-Britain are too many to enumerate on one side, and are all too atrocious to be palliated on the other. The press, that distinguished appendage of public liberty, has been prostituted by fallacy upon fallacy to the most contrary purposes, in a perfidious conspiracy to confound the good works of Government. To complete the horrid profanation of terms and ideas, the name of the Almighty has been introduced in the pulpits by ill designing preachers to excite and justify revolt and treason. I therefore command all Judges, Justices, and Sheriffs to use their utmost endeavours to enforce the laws for promoting Religion and Virtue, and restraining all Vice and Sedition; and I earnestly recommend to all Ministers of the Gospel, that they be vigilant and active in inculcating a due submission to the laws of God and man. I further exhort the infatuated multitudes of this Province, who have long suffered themselves to be conducted by certain well known Incendiaries and Traitors, by every means in their power, to a general reformation of manners, restitution of peace and good order, and a proper subjection to the laws and orders of this Province. -

LEQ: from Whom Did We Want to Be Independent, and on What Date Did We Declare Our Independence?

LEQ: From whom did we want to be independent, and on what date did we declare our independence? This reproduction of the Declaration of Independence was created by William Stone in 1823. This image is courtesy of archive.gov. LEQ: From whom did we want to be independent, and on what date did we declare our independence? Great Britain, July 4, 1776 This reproduction of the Declaration of Independence was created by William Stone in 1823. This image is courtesy of archive.gov. Declaring Independence The Declaration of Independence was signed by the Second Continental Congress on August 2, 1776. It had been approved on July 4, 1776. The signing took place in the Pennsylvania State House, in Philadelphia, a building which is now known as Independence Hall. This image is courtesy of the Architect of the Capitol. LEQ: From whom did we want to be independent, and on what date did we declare our independence? This reproduction of the Declaration of Independence was created by William Stone in 1823. This image is courtesy of archive.gov. LEQ: From whom did we want to be independent, and on what date did we declare our independence? Great Britain, July 4, 1776 This reproduction of the Declaration of Independence was created by William Stone in 1823. This image is courtesy of archive.gov. The First Continental Congress met in 1774 to protest the Intolerable Acts and other British policies that the colonists disliked. The First Continental Congress met in Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from September 5-October 26, 1774. This painting was created by Allyn Cox circa 1973-1974. -

Of the Declaration of Independence

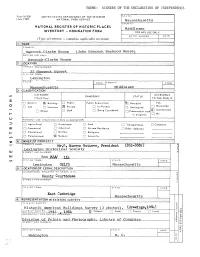

THEME: SIGNERS OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Massachusetts COUNTY- NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Middlesex INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) liiiiiiiiiiijji^ C OMMON: Hancock-Clarke House (John Hancock Boyhood House) AND/OR HISTORI C: Hancock-Clarke House ^ e^; ' : ' - o :;:^ •;.;- > • ^-^m STREET AND NUMBER: 35 Hancock Street CITY OR TOWN: Lexington STATE CODE COL NTY ' CODE Massachusetts Middlesex ii:2i/istPi£iIf oi;: : ; r - #. • : - •• • ; . -. • " ' •'•• -: ' ;: •; : :• • .; • •.•..: •' ,• :; ?:>•-;••: ; ; -;;:. ;, ;;-'- • • ^ STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Q District JX| Building 1 1 Public Public Acquisition: ^] Occupied Yes: . I 1 Restricted Q Site Q Structure 8 Private D tn Process D Unoccupied Q Object d] Both n Being Cons iaereaidered r-i — ji Preservationr> . work, X] Unrestricted in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) I | Agricultural | | Government Q Park I 1 Transportation 1 1 Comments Q Commercial [HI Industrial Q Private Residence (~1 Other fSperify) Q Educational 1 1 Military Q Religious Q Entertainment (Xi Museum Q Scientific . .. .* . ... ||i;|i|ii;;| iHI :-: ?;£;$?. CRT v • • • .• : • •; '. • ; '.•:; • ; •:, ]^S^M^M^^MM^ • v;: - • '•' •••- ^Sillislll OWNER-* NAME: Mr .G. Warren Butters. President (862-8885) Lexington Historical Society > (I STREET AND NUMBER: Box ffi/!/ llii CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODE Lexington 02173 Massachusetts ^;iGllf :0*Js{?£^ ii&ifci-fcfe SCR IP T I ON : : : • : iil •:•:•:•.•.•::•:•.:•:•'•:•:•. ••:::-^-:-. ::..,-...•. :.•:•••••.•:•,•••: •:••:•..' •, ••.-:' • .-•• • •' •• . • •' ' •'. •' COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: County Courthouse COUNTY: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: STATE CODE East Cambridge Massachusetts -i-i— |f | ;;;:||li|||ii>*f $$!$$; 1$ E X ) &T W G SU R V E Y S TITLE OF SURVEY: NUMBERENTRY Historic American Buildings Survey (2 photos). -

American Revolution

Note Cards 151. Battle of the Alamance May 1771 - An army recruited by the North Carolina government put down the rebellion of the Carolina Regulators at Alamance Creek. The leaders of the Regulators were executed. 152. Gaspée Incident In June, 1772, the British customs ship Gaspée ran around off the colonial coast. When the British went ashore for help, colonials boarded the ship and burned it. They were sent to Britain for trial. Colonial outrage led to the widespread formation of Committees of Correspondence. 153. Governor Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts A Boston-born merchant who served as the Royal Governor of Massachusetts from 1771 to 1774. Even before becoming Governor, Hutchinson had been a supporter of Parliament's right to tax the colonies, and his home had been burned by a mob during the Stamp Acts riots in 1765. In 1773 his refusal to comply with demands to prohibit an East India Company ship from unloading its cargo percipitated the Boston Tea Party. He fled to England in 1774, where he spent the remainder of his life. 154. Committees of Correspondence These started as groups of private citizens in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and New York who, in 1763, began circulating information about opposition to British trade measures. The first government-organized committee appeared in Massachusetts in 1764. Other colonies created their own committtees in order to exchange information and organize protests to British trade regulations. The Committees became particularly active following the Gaspee Incident. 155. Lord North Prime Minister of England from 1770 to 1782. Although he repealed the Townshend Acts, he generally went along with King George III's repressive policies towards the colonies even though he personally considered them wrong. -

Rhode Island Genealogy Research

Rhode Island Genealogy Research Indigenous peoples The peoples living in the area now called Rhode Island before Europeans arrived were the Niantic, the Narragansett, the Wampanoag, the Pequot and the Nipmuck. Drawing of Roger Williams and Native Americans - http://www.history.com/topics/roger-williams The Pequots had some land in southwestern Rhode Island. They attempted to maintain their autonomy and made war on the European settlers. This led to their near-extinction as the colonists, allied with the Narragansett and the Mohegan tribes, defeated the Pequot. The Nipmuc Indians occupied some land in Northern Rhode Island. It is believed that most of their survivors of King Phillips’s War fled into Canada. The Niantics lived in the southern part of mainland Rhode Island. Their leader, Ninigret, prolonged their viability by keeping distance from the Native Americans who rebelled against the colonists. Roger Williams socialized and negotiated a land treaty with Narragansett and Wampanoag leaders on his arrival in the 1630s. Canonicus, the sachem, or ruler, of the Narragansetts, became a close friend of Williams until his death in 1647. Massasoit headed the Wampanoags, and Williams helped bring some degree of peace between these two nations. King Phillip’s War: In the 1670s, the leader of the Wampanoags was Philip, the son of Massasoit. He attempted to unify New England’s Native American groups in order to overthrow the colonists’ grip on the region. Betrayal and intrigue escalated the situation into what became known as King Philip’s War. By summer 1676, the Narragansetts had been broken and the Wampanoags decimated; Philip’s surviving family members were sold into slavery.