PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embodiment and Devotion in the Très Riches Heures (Or, the Possibilities of a Post-Theoretical Art History)

John Carroll University Carroll Collected 2020 Faculty Bibliography Faculty Bibliographies Community Homepage 2020 Embodiment and Devotion in the Très Riches Heures (or, the Possibilities of a Post-Theoretical Art History) Gerald B. Guest Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/fac_bib_2020 Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Embodiment and Devotion in the Très Riches Heures (or, the Possibilities of a Post-Theoretical Art History) Gerald B. Guest, John Carroll University Recommended Citation: Gerald B. Guest, “Embodiment and Devotion in the Très Riches Heures (or, the Possibilities of a Post-Theoretical Art History),” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 6 (2020): 1-16. Introduction likely created with the express intention of stimulating the Duke’s desires in multiple This article seeks to further our under- and even contradictory ways. standing of the Très Riches Heures as both a devotional manuscript and as a work of art through an extended consideration of one of its key images, the Fall of Humanity (Fig. 1). I will be especially concerned in this analysis with the ways in which the book’s patron, Jean, duc de Berry (died 1416), might have experienced the manuscript if he had lived to see its completion. In nego- tiating what I see as a tension between the book’s devotional concerns and its aesthet- ics, I will argue for an approach that I characterize here as post-theoretical. It will take the full space of this article to explain what that term means and how it might be applied to a work of art from the late Middle Ages. -

Très Riches Heures Du Duc De Berry 1 Très Riches Heures Du Duc De Berry

Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry 1 Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry or simply the Très Riches Heures (The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry) is a richly decorated Book of Hours (containing prayers to be said by the lay faithful at each of the canonical hours of the day) commissioned by John, Duke of Berry, around 1410. It is probably the most important illuminated manuscript of the 15th century, "le roi des manuscrits enluminés" ("the king of illuminated manuscripts"). The Très Riches Heures consists of 416 pages, including 131 with large miniatures and many more with border decorations or historiated initials, that are among the high points of International Gothic painting in spite of their small size. There are 300 decorated capital letters. The book was worked on, over a period of nearly a century, in three main campaigns, led by the Limbourg brothers, Barthélemy van Eyck, and Jean Colombe. The book is now Ms. 65 in the Musée Condé, Chantilly, France. The Limbourg brothers used very fine brushes, and expensive paints to make the paintings. Calendar A generalized calendar (not specific to any year) of church Page from the calendar of the Très Riches Heures showing Jean, feasts and saints' days, often illuminated, is a usual part of Duc de Berry's household exchanging New Year gifts. The Duke a book of hours, but the illustrations of the months in the is seated at the right, in blue. Très Riches Heures are exceptional and innovative in their scope, and the best known element of the decoration of the manuscript. -

Interart Studies from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era: Stylistic Parallels Between English Poetry and the Visual Arts Roberta Aronson

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 1-1-2003 Interart Studies from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era: Stylistic Parallels between English Poetry and the Visual Arts Roberta Aronson Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Aronson, R. (2003). Interart Studies from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era: Stylistic Parallels between English Poetry and the Visual Arts (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/11 This Worldwide Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interart Studies from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era: Stylistic Parallels between English Poetry and the Visual Arts A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Roberta Chivers Aronson October 1, 2003 @Copyright by Roberta Chivers Aronson, 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my appreciation to my many colleagues and family members whose collective support and inspiration underlie all that I do: • To my Provost, Dr. Ralph Pearson, for his kind professional encouragement, • To my Dean, Dr. Connie Ramirez, who creates a truly collegial and supportive academic environment, • To my Director, Dr. Albert C. Labriola, for his intellectual generosity and guidance; to Dr. Bernard Beranek for his enthusiasm and thoughtful conversation; and to Dr. -

14 CH14 P468-503.Qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 468 14 CH14 P468-503.Qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 469 CHAPTER 14 Artistic Innovations in Fifteenth-Century Northern Europe

14_CH14_P468-503.qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 468 14_CH14_P468-503.qxp 9/10/09 11:40 Page 469 CHAPTER 14 Artistic Innovations in Fifteenth-Century Northern Europe HE GREAT CATHEDRALS OF EUROPE’S GOTHIC ERA—THE PRODUCTS of collaboration among church officials, rulers, and the laity—were mostly completed by 1400. As monuments of Christian faith, they T exemplify the medieval outlook. But cathedrals are also monuments of cities, where major social and economic changes would set the stage for the modern world. As the fourteenth century came to an end, the were emboldened to seek more autonomy from the traditional medieval agrarian economy was giving way to an economy based aristocracy, who sought to maintain the feudal status quo. on manufacturing and trade, activities that took place in urban Two of the most far-reaching changes concerned increased centers. A social shift accompanied this economic change. Many literacy and changes in religious expression. In the fourteenth city dwellers belonged to the middle classes, whose upper ranks century, the pope left Rome for Avignon, France, where his enjoyed literacy, leisure, and disposable income. With these successors resided until 1378. On the papacy’s return to Rome, advantages, the middle classes gained greater social and cultural however, a faction remained in France and elected their own pope. influence than they had wielded in the Middle Ages, when the This created a schism in the Church that only ended in 1417. But clergy and aristocracy had dominated. This transformation had a the damage to the integrity of the papacy had already been done. -

Les Très Riches Heures Du Duc De Berry

Les très riches heures du Duc de Berry Sommaire 1. INTRODUCTION 2 1.1 International Gothic Style 2 1.2 Masters of illumination 2 2. LES TRES RICHES HEURES DU DUC DE BERRY 2 2.1 January 2 2.2 February 2 2.3 March 2 2.4 April 2 2.5 May 3 2.6 June 3 2.7 July 3 2.8 August 3 2.9 September 3 2.10 October 3 2.11 November 3 2.12 December 3 3. WHAT IS THE TRÈS RICHES HEURES? 3 4. WHO PAINTED THE TRÈS RICHES HEURES? 3 5. WHO WAS THEIR PATRON? 4 6. HOW DID THEY PAINT THE TRÈS RICHES HEURES? 4 7. MEDIEVAL GLOSSARY 4 7.1 Book of Hours 4 7.2 Enamel 4 7.3 Genre 4 7.4 Illuminated manuscripts 4 7.5 Limburg Brothers 5 7.6 miniature 5 7.7 Paper 5 7.8 Parchment 6 7.9 Woodcut 6 1. Introduction The original Riches Heures manuscript is stored in the Chantilly museum, but is so degraded that it is no longer available to the public... except for WebMuseum visitors! 1.1 International Gothic Style By the end of the 14th century, the fusion of Italian and Northern European art had led to the development of an International Gothic style. For the next quarter of a century, leading artists travelled from Italy to France, and vice versa, and all over Europe. As a consequence, ideas spread and merged, until eventually painters in this International Gothic style could be found in France, Italy, England, Germany, Austria and Bohemia. -

Revisiting the Monument Fifty Years Since Panofsky’S Tomb Sculpture

REVISITING THE MONUMENT FIFTY YEARS SINCE PANOFSKY’S TOMB SCULPTURE EDITED BY ANN ADAMS JESSICA BARKER Revisiting The Monument: Fifty Years since Panofsky’s Tomb Sculpture Edited by Ann Adams and Jessica Barker With contributions by: Ann Adams Jessica Barker James Alexander Cameron Martha Dunkelman Shirin Fozi Sanne Frequin Robert Marcoux Susie Nash Geoffrey Nuttall Luca Palozzi Matthew Reeves Kim Woods Series Editor: Alixe Bovey Courtauld Books Online is published by the Research Forum of The Courtauld Institute of Art Somerset House, Strand, London WC2R 0RN © 2016, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. ISBN: 978-1-907485-06-0 Courtauld Books Online Advisory Board: Paul Binski (University of Cambridge) Thomas Crow (Institute of Fine Arts) Michael Ann Holly (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute) Courtauld Books Online is a series of scholarly books published by The Courtauld Institute of Art. The series includes research publications that emerge from Courtauld Research Forum events and Courtauld projects involving an array of outstanding scholars from art history and conservation across the world. It is an open-access series, freely available to readers to read online and to download without charge. The series has been developed in the context of research priorities of The Courtauld which emphasise the extension of knowledge in the fields of art history and conservation, and the development of new patterns of explanation. For more information contact [email protected] All chapters of this book are available for download at courtauld.ac.uk/research/courtauld-books-online Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of images reproduced in this publication. -

The Black Death and Its Effect on Fourteenth- and Fifteenth-Century Art

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 The lB ack Death and its effect on fourteenth- and fifteenth-century art Anna Louise DesOrmeaux Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation DesOrmeaux, Anna Louise, "The lB ack Death and its effect on fourteenth- and fifteenth-century art" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 1641. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1641 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BLACK DEATH AND ITS EFFECT ON FOURTEENTH- AND FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ART A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Anna L. DesOrmeaux B.A., Louisiana State University, 2004 May 2007 To my parents, Johnny and Annette DesOrmeaux, who stressed the importance of a formal education and supported me in every way. You are my most influential teachers. ii Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Mark Zucker, my advisor with eagle eyes and a red sword, for his indispensable guidance on any day of the week. I also thank Drs. Justin Walsh, Marchita Mauck, and Kirsten Noreen, who have helped me greatly throughout my research with brilliant observations and suggestions. -

The Spitz Master: a Parisian Book of Hours

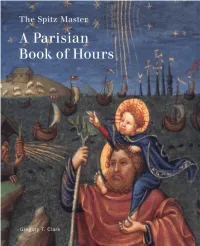

The Spitz Master A Parisian Book of Hours The Spitz Master A Parisian Book of Hours Gregory T. Clark GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los Angeles For Nicole Reynaud and François Avril © 2003 J. Paul Getty Trust Cover: Spitz Master (French, act. ca. 1415-25). Saint Getty Publications Christopher Carrying the Christ Child [detail]. 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Spitz Hours, Paris, ca. 1420. Tempera, gold, Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 and ink on parchment bound between www.getty.edu pasteboard covered with red silk velvet, 247 leaves, 20.3 x 14.8 cm (715/ie x 5% in.). Christopher Hudson, Publisher Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 57, Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief 94.ML.26, fol. 42V (see Figure 7). Mollie Holtman and Tobi Kaplan, Editors Frontispiece: Diane Mark-Walker, Copy Editor Spitz Master, The Virgin and Child Jeffrey Cohen, Series Designer Enthroned [detail]. Spitz Hours, fol. 33V Suzanne Watson, Production Coordinator (see Figure 6). Christopher Foster, Photographer Typeset by G&S Typesetters, Inc., The books of the Bible are cited according Austin, Texas to their designations in the Douay-Rheims Printed in Hong Kong by Imago version translated from the Latin Vulgate. Library of Congress Full-page illustrations from the Spitz Hours Cataloging-in-Publication Data are reproduced at actual size. Clark, Gregory T., 1951- All photographs are copyrighted by the The Spitz master : a Parisian book of issuing institutions, unless otherwise noted. hours / Gregory T. Clark. p. cm. — (Getty Museum studies on art) Includes bibliographic references. ISBN 0-89236-712-1 i. Spitz hours—Illustrations. -

The Art of Illumination : the Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean De France, Duc De Berry Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE ART OF ILLUMINATION : THE LIMBOURG BROTHERS AND THE BELLES HEURES OF JEAN DE FRANCE, DUC DE BERRY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Timothy B. Husband | 388 pages | 10 Sep 2013 | Metropolitan Museum of Art | 9780300200225 | English | New York, United States The Art of Illumination : The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry PDF Book Hidden category: Pages with script errors. The exhibition will elucidate the manuscript, its artists—the young Franco-Netherlandish Limbourg Brothers—and its patron, Jean de France, duc de Berry. Centeno, Janet G. Stein on Wednesday, May 26 at pm Comments Off. His monstrous beauty can serve as a point of departure leading us toward new understandings of a manuscript that is far less familiar than it seems. See for example, Pierre J. More Details Brown, Katharine Reynolds. According to the Gospel of Luke, the sun at upper right dimmed; the Gospel of Matthew describes graves opening and the dead rising, as seen here in the foreground. The finished book might have given him the chance to seek forgiveness while contemplating both his public and private sins during a time of social and political crisis for the French monarchy. Les Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry - with its subtle variation of line, painstaking technique, and minute rendering of detail - marks the highpoint of book illustration in the stylized, courtly idiom known as the International Gothic. Welcome back. In this image, Catherine is depicted as a scholarly and educated individual. London: Public Monuments and Sculpture Association, An estate document listing his worldly goods in the wake of his July death has recently been studied by Donatella Nebbiai. -

Tres Riches Heures - Saylor.Org Pdf

INNOVATION and EXPERIMENTATION: EARLY NORTHERN RENAISSANCE ART (Robert Campin and the Limbourg Brothers) EARLY NORTHERN RENAISSANCE Online Links: Robert Campin - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Campin - Smarthistory Campin's Merode Altarpiece - Metropolitan Museum of Art Campin - Oneonta.edu Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry – Wikipedia Tres Riches Heures - saylor.org pdf Tres Riches Heures with medieval music – YouTube The Hidden Masters of the Middle Ages, the Limbourg Brothers Documentary – YouTube Belles Heures after Duc of Berry Lecture - Metropolitan Museum of Art Tres Riches Heures - Oneonta.edu Master of Flemalle (Robert Campin). Merode Altarpiece, c. 1425-1428, oil on wood The first, and perhaps most decisive, phase of the pictorial revolution in Flanders can be seen in the work of an artist formerly known as the Master of Flemalle (after the fragments of a large altar from Flemalle), who was undoubtedly Robert Campin, the foremost painter of Tournai. We can trace his career in documents from 1406 to his death in 1444, although it declined after his conviction in 1428 for adultery. His finest work is the Merode Altarpiece, which he must have painted soon after 1425. If we compare it to the Franco-Flemish pictures of the International Style, we see that it falls within the same tradition. Yet we also recognize in it a new pictorial experience. Campin maintained the spatial conventions typical of the International Gothic style; the abrupt recession of the bench toward the back of the room, the sharply uplifted floor and tabletop, and the disproportionate relationship between the figures and the architectural space create an inescapable impression of instability. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Op zoek naar de gebroeders Limburg: de Très Riches Heures in het Musée Condé in Chantilly, Het Wapenboek Gelre in de Koninklijke Bibliotheek Albert I in Brussel en Jan Maelwael en zijn neefjes Polequin, Jehannequin en Herman van Limburg Colenbrander, H.T. Publication date 2006 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Colenbrander, H. T. (2006). Op zoek naar de gebroeders Limburg: de Très Riches Heures in het Musée Condé in Chantilly, Het Wapenboek Gelre in de Koninklijke Bibliotheek Albert I in Brussel en Jan Maelwael en zijn neefjes Polequin, Jehannequin en Herman van Limburg. in eigen beheer. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 1.1. -

Unraveling Christ's Passion

UNRAVELING CHRIST’S PASSION: ARCHBISHOP DALMAU DE MUR, PATRON AND COLLECTOR, AND FRANCO-FLEMISH TAPESTRIES IN FIFTEENTH-CENTURY SPAIN by Katherine M. Dimitroff BA, University of California, San Diego, 1996 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 1999 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Katherine M. Dimitroff It was defended on March 28, 2008 and approved by David Wilkins, Professor Emeritus, History of Art & Architecture Ann Sutherland Harris, Professor, History of Art & Architecture Bruce L. Venarde, Associate Professor, History Dissertation Advisor: M. Alison Stones, Professor, History of Art & Architecture ii Copyright © by Katherine M. Dimitroff 2008 iii UNRAVELING CHRIST’S PASSION: ARCHBISHOP DALMAU DE MUR, PATRON AND COLLECTOR, AND FRANCO-FLEMISH TAPESTRIES IN FIFTEENTH-CENTURY SPAIN Katherine M. Dimitroff, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2008 This dissertation considers the artistic patronage of Dalmau de Mur i de Cervelló (1376– 1456), a high-ranking Catalan prelate little known outside Spain. As Bishop of Girona (1416– 1419), Archbishop of Tarragona (1419–1431) and Archbishop of Zaragoza (1431–1456), Dalmau de Mur commissioned and acquired of works of art, including illuminated manuscripts, panel paintings, sculpted altarpieces, metalwork and tapestries. Many of these objects survive, including two remarkable tapestries depicting the Passion of Christ that he bequeathed to Zaragoza Cathedral upon his death in 1456. Surviving primary documents, particularly Dalmau de Mur’s testament and the Cathedral inventory of 1521, show that his collection was still more significant.