A Case Study of the Supporter Groups of the Colorado Rapids and Glocalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section Header

SECTION HEADER 2009 NLL Media Guide and Record Book 1 SECTION HEADER Follow the Entire 2010 NLL Season Live on the NLL Network at NLL.com 2010 NLL MEDIA GUIDE Table of Contents NLL Introduction Table of Contents/Staff Directory ........................1 Gait Introduction to the NLL.......................................2 2010 Division and Playoff Formats......................3 Lacrosse Talk.......................................................4 Team Information Boston Blazers .................................................5-9 Buffalo Bandits............................................10-16 Calgary Roughnecks ....................................17-22 Colorado Mammoth.....................................23-29 Edmonton Rush ...........................................30-34 Minnesota Swarm........................................35-40 Orlando Titans..............................................41-45 Philadelphia Wings......................................46-52 Rochester Knighthawks ...............................53-59 Toronto Rock................................................60-65 Washington Stealth.....................................66-71 History and Records League Award Winners and Honors .............72-73 League All-Pros............................................74-78 All-Rookie Teams ..............................................79 Individual Records/Coaching Records ...............80 National Lacrosse League All-Time Single-Season Records........................81 Staff Directory Yearly Leaders..............................................82-83 -

Violence and Death in Argentinean Soccer in the New Millennium: Who Is Involved and What Is at Stake? Fernando Segura M Trejo, Diego Murzi, Belen Nassar

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archive Ouverte en Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication Violence and death in Argentinean soccer in the new Millennium: Who is involved and what is at stake? Fernando Segura M Trejo, Diego Murzi, Belen Nassar To cite this version: Fernando Segura M Trejo, Diego Murzi, Belen Nassar. Violence and death in Argentinean soccer in the new Millennium: Who is involved and what is at stake?. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, SAGE Publications, In press, 10.1177/1012690217748929. hal-02162050 HAL Id: hal-02162050 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02162050 Submitted on 21 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Violence and death in Argentinean soccer in the new Millennium: Who is involved and what is at stake? Trejo Cide, Mexico Ufg, Diego Brazil, Fernando Segura, M Trejo, Carretera Touluca, Fernando Segura M Trejo, Diego Murzi, Belen Nassar To cite this version: Trejo Cide, Mexico Ufg, Diego Brazil, Fernando Segura, M Trejo, et al.. Violence and death in Argen- tinean soccer in the new Millennium: Who is involved and what is at stake?. -

Mls Cup Ticket Giveaway Official Rules No

MLS CUP TICKET GIVEAWAY OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE NECESSARY TO ENTER. OPEN TO LEGAL RESIDENTS OF THE UNITED STATES (EXCLUDING RESIDENTS OF RHODE ISLAND, PUERTO RICO, THE U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS, AND OTHER COMMONWEALTHS, TERRITORIES AND POSSESSIONS AND WHERE OTHERWISE PROHIBITED BY LAW), WHO HAVE REACHED 18 YEARS OF AGE NO LATER THAN NOVEMBER 1, 2016. 1. By entering this CONTEST (the "Contest") and accepting the terms herein, you agree to be bound by the following rules ("Official Rules"), which constitute a binding agreement between you, on one hand, and SeatGeek, Inc., on the other (“SeatGeek”). SeatGeek and any website companies hosting and promoting the Contest, their respective parent companies, affiliates, subsidiaries, advertising and promotion agencies, and all of their agents, officers, directors, shareholders, employees, and agents are referred to as the Contest Entities. These Official Rules apply only to the Contest and not to any other sweepstakes or contest sponsored by SeatGeek. 2. CONTEST DETAILS: SeatGeek shall give away, for no consideration, 4 VIP ticket packages for the 2016 MLS Cup. The Contest will be promoted by SeatGeek during November and December 2016. 3. ELIGIBILITY: This Contest is open only to legal residents of the United States (excluding residents of Rhode Island, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and other commonwealths, territories and possessions, and where otherwise prohibited by law) who have reached 18 YEARS OF AGE no later than November 1, 2016 ("Entrants"). Individuals in any of the following categories are not eligible to enter or win this Contest: (a) employees of SeatGeek or their affiliates, parents, subsidiaries, professional advisors and promotional agencies or other entities involved in the sweepstakes; and (b) individuals who are immediate family members or who reside in the same household as any individual described above. -

8-24-17 Transcript Bulletin

FRONT PAGE A1FRONT PAGE A1 TOOELETRANSCRIPT Tooele girls SERVING defeat TOOELE COUNTY defending SINCE 1894 state champs ULLETIN See B1 B THURSDAY August 24, 2017 www.TooeleOnline.com Vol. 124 No. 25 $1.00 Study committee picks top 2 forms of government TIM GILLIE STAFF WRITER to keep the five-member commission, the expanded by the committee, it remains for legislative representation determined criteria. Each cri- After eight months and county commission and the seven-member commission, a viable option because if vot- and the county executive func- terion had a weighted value, 500 hours of meetings and appointed county manager/ and the elected county execu- ers reject a change, the three- tion. based on the committee’s research, the Tooele County elected county council on the tive with an elected county member commission will be Committee members also determination of the priority of Government Study Committee table for future consideration council. retained. completed a worksheet where the criteria. has narrowed the forms of gov- at its Wednesday night meet- Even though the current Prior to the meeting, study they scored the legislative and Richard Mitchell, study ernment it will consider from ing. three-member commission committee members completed executive function of each committee chairman, collected five options to two. Gone from future study is form of government will not be an Excel spreadsheet indicat- form of government on a scale The study committee voted the current three-member one of the final options studied ing their general preferences of one to 10 on 10 previously SEE STUDY PAGE A7 ➤ Health dept. -

El Aguante En Una Barra Brava: Apuntes Para La Construcción De Su Identidad1 Aguante in a Barra Brava – Some Notes on Building Its Own Identity

El aguante en una barra brava: apuntes para la construcción de su identidad1 Aguante in a barra brava – Some notes on building its own identity John Alexander Castro-Lozano2 Resumen Este trabajo es el resultado de la investigación realizada entre el segundo semestre de 2010 y el primero de 2012 con un grupo de hinchas organizados de Millonarios F.C., lo que comúnmente se conoce como barra brava. Aquí se presenta una revisión bibliográfica sobre la producción teórica en torno a grupos organizados de hinchas del fútbol. Asimismo, se explica cómo acercarse y estar presente con la barra. También se exponen los hallazgos obtenidos a través de la descripción y la participación, técnicas particulares de la etnografía. Finalmente, se reflexiona a partir delaguante , una noción propia del grupo seleccionado y la manera como éste se convierte en un elemento constructor de identidad. Palabras clave: barra brava, Blue Rain, aguante, identidad, Millonarios F.C. Abstract This paper presents the results of a research carried out between the second semester of 2010 and the first one of 2012 within a fan group of Millonarios FC, commonly known as “barra brava”. There is a literature review on theoretical issues about football fans. The paper also explains how to join and interact into a fans’ group. In addition, findings obtained by means of the description and involvement into the fans‘group, are presented through particular ethnography technique. Finally, some reflections are made about “aguante”, a concept built within the selected group and how this concept has become an element to build identity. Keywords: barra brava, Blue Rain, aguante, identity, Millonarios FC. -

MLS Game Guide

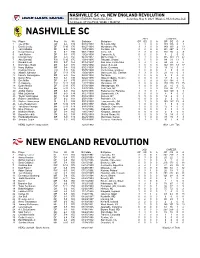

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

Download This Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 8, 2019 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] MAYOR LIGHTFOOT, THE CHICAGO PARK DISTRICT AND CHICAGO FIRE SOCCER CLUB ANNOUNCE THE TEAM’S RETURN TO SOLDIER FIELD The Fire to Return to Soldier Field starting in March 2020 CHICAGO – Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot, Chicago Park District Superintendent & CEO Mike Kelly, and the Chicago Fire Soccer Club today announced that the team will return to Soldier Field to play their home games starting in 2020. SeatGeek Stadium in Bridgeview, Illinois has been home to the Fire since 2006, and the team will continue to utilize the stadium as a training facility and headquarters for Chicago Fire Youth development programs. “Chicago is the greatest sports town in the world, and I am thrilled to welcome the Chicago Fire back home to Solider Field, giving families in every one of our neighborhoods a chance to cheer for their team in the heart of our beautiful downtown,” said Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot. “From arts, culture, business, sports, and entertainment, Chicago is second to none in creating a dynamic destination for residents and visitors alike, and I look forward to many years of exciting Chicago Fire soccer to come.” The Chicago Fire was founded in 1997 and began playing in Major League Soccer in 1998. The Fire won the MLS Cup and the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup its first season, and additional U.S. Open Cups in 2000, 2003, and 2006. As an early MLS expansion team, the Fire played at Soldier Field from 1998 until 2001 and then from 2003 to 2005 before moving to Bridgeview in 2006. -

Larimer County, Colorado 2016 Economic Profile Table of Contents

Larimer County, Colorado 2016 Economic Profile Table of Contents This workbook contains multiple worksheets of data for Larimer County. Please select the tabs at the bottom of this workbook to access contents. If tabs are not visible, maximize your Microsoft Excel viewing window. Workbook Contents Worksheet 1: Population & Cities Worksheet 2: Employment & Labor Force Worksheet 3: Education Worksheet 4: Cost of Living, Income, & Housing Worksheet 5: Tax Rates Worksheet 6: Transportation Worksheet 7: Commercial Real Estate Worksheet 8: Cultural Institutions Worksheet 9: Economic Development Partners To print all workbook pages at the same time, select "Print" from the File menu. In the print menu box and "Print What" section, select "Entire Workbook." Larimer County, Colorado 2016 Economic Profile Population & Cities Population and Households, 2015 Gender and Age Distribution, 2015 Population Households Male 49.6% Larimer County 332,832 142,779 Female 50.4% Berthoud (MCP) 5,619 2,240 Estes Park 6,209 4,235 Median age 36.7 Fort Collins 160,935 65,760 0 to 14 years 17.5% Johnstown (MCP) 790 389 15 to 29 years 23.9% Loveland 74,461 30,946 30 to 44 years 19.2% Timnath 2,418 914 45 to 59 years 19.0% Wellington 7,662 2,699 60 to 74 years 14.8% Windsor (MCP) 6,496 2,294 75 to 89 years 4.9% Unincorporated Area 68,242 33,302 90+ years 0.7% Note: MCP indicates multi-county place. Figures reported are the portion of total Note: Percentages may not add due to rounding. population and households located in the given county. -

Fan Guide 2012

FAN GUIDE 2012 AN A-Z DIRECTORY OF FACILITY SERVICES FOR OUR GUESTS STADIUM FACTS LARGEST PROFESSIONAL SOCCER STADIUM & COMPLEX IN THE UNITED STATES CONTACT INFORMATION 6000 Victory Way Commerce City, CO 80022 Phone 303.727.3500 Website DicksSportingGoodsPark.com FUN FACTS Sporting Event Seating Capacity 18,000 Concert Seating Capacity 27,000 Suites 21 Club Seats 200 ADA Seats 171 + 171 Companion Seats Stadium Field Soccer Field=120 Yards by 75 Yards / Rugby Field=108 Yards by 75 yards Sports Complex Fields 24 Fields Cost to build Dick’s Sporting Goods Park $131 Million - which were private and public funds Land - 63 acres of turf alone - 140 acres makes up the whole complex KEY DATES Groundbreaking September 28, 2005 Opening Event April 7, 2007, Colorado Rapids v. D.C. United 2007 Major League Soccer Season Opener First Concert June 30, 2007, Kenny Chesney, Sugarland and Pat Green Other July 19, 2007, Major League Soccer All-Star Game (MLS All Stars v. Celtic) November 19, 2009 World Cup Qualifier (United States v. Guatemala) 2008, 2009, 2012 Home fo the Mile High Music Festival September 2, 3, 4, 2011 Labor Day Weekend Last stop on the PHISH Summer Tour TABLE OF CONTENTS DICK’S SPORTING GOODS PARK Employment .....................11 See Something, Say Something .......19 Entry to Field of Play Signs, Banners and Flags ............20 / Performance Area ................11 Smoking ........................20 30 Minute Drop-Off Family Restrooms .................11 Soccer Fields / Playing Fields .........20 / Pick-up Parking Zone ..............1 Fighting .........................11 Social Media .....................21 Advance Ticket Sales. .1 First Aid .........................11 Sponsorship Advertising .............21 Age Restrictions ....................1 Flash Seats ......................11 Stadium Rental / Facility Rental .......21 Alcoholic Beverage Policies ...........1 Food and Beverage ................12 Stage Configurations ...............21 Altitude Authentics Gate Opening Times ................12 Strollers. -

Universidad Politécnica Salesiana Sede Quito

UNIVERSIDAD POLITÉCNICA SALESIANA SEDE QUITO CARRERA: COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL Tesis previa a la obtención del título de: LICENCIADA EN COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL MENCIÓN PERIODISMO INVESTIGATIVO TEMA: “FUTBOL, IDEOLOGÍA Y ALIENACIÓN. EL CASO DE LAS BARRAS BRAVAS EN ECUADOR, ESTUDIO DEL CASO SOCIEDAD DEPORTIVO QUITO- LIGA DEPORTIVA UNIVERSITARIA DE QUITO” AUTORAS: ANDREA PAOLA MONTENEGRO GUAYASAMÍN MARÍA JOSÉ VELA VITERI DIRECTOR: LEONARDO OGAZ Quito, octubre de 2013 DECLARATORIA DE RESPONSABILIDAD Y AUTORIZACIÓN DE USO DELTRABAJO DE GRADO Nosotros Andrea Paola Montenegro Guayasamín con CI. 1716817083 y María José Vela Viteri con CI. 1720995073 autorizamos a la Universidad Politécnica Salesiana la publicación total o parcial de este trabajo de grado y su reproducción sin fines de lucro. Además declaramos que los conceptos y análisis desarrollados y las conclusiones del presente trabajo son de exclusiva responsabilidad de las autoras. Quito, septiembre del 2013 ---------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------- Andrea Paola Montenegro Guayasamín María José Vela Viteri CI. 1716817083 CI. 1720995073 DEDICATORIA Quiero dedicar esta Tesis de grado a mi madre y mi hija, quienes han sido mi apoyo fundamental y el motor de cada día en estos años universitarios, a Dios por darme fortaleza y a mis hermanos quienes siempre me han dado su ayuda cuando lo he necesitado, y mi mejor amigo Willy por todos sus consejos y apoyo moral. Andrea Montenegro Guayasamín DEDICATORIA Dedico este trabajo principalmente a la vida por permitirme -

19 Lc 117 0772 H. R

19 LC 117 0772 House Resolution 162 By: Representatives Harrell of the 106th, Hutchinson of the 107th, Thomas of the 56th, Gardner of the 57th, Cannon of the 58th, and others A RESOLUTION 1 Recognizing and commending Atlanta United FC for winning the 2018 MLS Cup; and for 2 other purposes. 3 WHEREAS, on December 8, 2018, Atlanta United FC defeated the Portland Timbers 2-0 to 4 win the 2018 MLS Cup; and 5 WHEREAS, Atlanta United FC Forward Josef Martinez was named MLS League MVP, 6 scored the first goal in the championship match, and shattered the record for the most goals 7 scored in a single season, with 31 goals; and 8 WHEREAS, Martinez's individual season was one filled with many accolades, as he also 9 won the MLS Golden Boot, MLS All-Star Game MVP, and MLS Cup MVP, making him the 10 first MLS player to win league MVP, All-Star MVP, and MLS Cup MVP in the same season; 11 and 12 WHEREAS, Atlanta United FC became the second team in MLS history to score 70 or more 13 goals in consecutive seasons; and 14 WHEREAS, along with Josef Martinez's premier season, coach Gerardo "Tata" Martino won 15 the MLS Coach of the Year, leading the team to an overall record of 21-7-6, an 11-2-4 record 16 at home, and the MLS Cup Championship; and 17 WHEREAS, in only its second season, Arthur Blank's innovative vision and strategy for 18 bringing an MLS team to Atlanta has led to Atlanta United FC being named Major League 19 Soccer's most valuable team; and 20 WHEREAS, Mercedes-Benz Stadium has provided Atlanta United FC a premier venue for 21 all its home games, providing its fans and visitors a unique experience that includes H. -

Thanks to Our Sponsor 6U Youth Soccer League

Thanks to our Sponsor 6U Youth Soccer League - Game Schedule (Page 1 of 2) Date Time HomeTeam AwayTeam Field Location 04/14/2016 6pm COLORADO RAPIDS DC UNITED #1 Civic Park 04/14/2016 6pm HOUSTON DYNAMO VANCOUVER WHITECAPS #2 Civic Park 04/14/2016 6pm NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION SAN JOSE EARTHQUAKES #5 Civic Park 04/14/2016 7pm MONTREAL IMPACT LA GALAXY #3 Civic Park 04/14/2016 7pm PORTLAND TIMBERS CHICAGO FIRE #4 Civic Park 04/16/2016 9am VANCOUVER WHITECAPS NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION #1 Civic Park 04/16/2016 9am DC UNITED MONTREAL IMPACT #2 Civic Park 04/16/2016 9am LA GALAXY HOUSTON DYNAMO #3 Civic Park 04/16/2016 9am CHICAGO FIRE SAN JOSE EARTHQUAKES #4 Civic Park 04/16/2016 10am PORTLAND TIMBERS COLORADO RAPIDS #1 Civic Park 04/21/2016 6pm MONTREAL IMPACT PORTLAND TIMBERS #1 Civic Park 04/21/2016 6pm NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION LA GALAXY #2 Civic Park 04/21/2016 6pm COLORADO RAPIDS CHICAGO FIRE #5 Civic Park 04/21/2016 7pm SAN JOSE EARTHQUAKES VANCOUVER WHITECAPS #4 Civic Park 04/21/2016 7pm HOUSTON DYNAMO DC UNITED #3 Civic Park 6U Youth Soccer League - Game Schedule (Page 2 of 2) Date Time HomeTeam AwayTeam Field Location 04/23/2016 9am LA GALAXY SAN JOSE EARTHQUAKES #1 Civic Park 04/23/2016 9am PORTLAND TIMBERS HOUSTON DYNAMO #2 Civic Park 04/23/2016 9am DC UNITED NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION #3 Civic Park 04/23/2016 9am CHICAGO FIRE VANCOUVER WHITECAPS #4 Civic Park 04/23/2016 10am COLORADO RAPIDS MONTREAL IMPACT #1 Civic Park 4/26/2016 6pm DC UNITED PORTLAND TIMBERS #1 Civic Park MAKE UP GAME 4/26/2016 6pm SAN JOSE EARTHQUAKES HOUSTON DYNAMO #2