Cheek by Jowl: Reframing Complicity in Web-Streams of Measure for Measure Peter Kirwan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

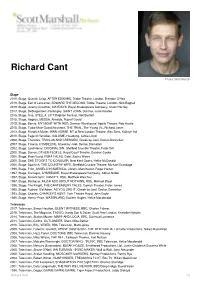

Richard Cant

Richard Cant Photo: Wolf Marloh Stage 2019, Stage, Quentin Crisp, AFTER EDWARD, Globe Theatre, London, Brendan O'Hea 2019, Stage, Earl of Lancaster, EDWARD THE SECOND, Globe Theatre, London, Nick Bagnall 2018, Stage, Jeremy Crowther, MAYDAYS, Royal Shakespeare Company, Owen Horsley 2017, Stage, DeStogumber/ Poulengey, SAINT JOAN, Donmar, Josie Rourke 2016, Stage, One, STELLA, LIFT/Brighton Festival, Neil Bartlett 2015, Stage, Aegeus, MEDEA, Almeida, Rupert Goold 2015, Stage, Bernie, MY NIGHT WITH REG, Donmar Warehouse/ Apollo Theatre, Rob Hastie 2015, Stage, Tudor/Male Guard/Assistant, THE TRIAL, The Young Vic, Richard Jones 2013, Stage, Friedrich Muller, WAR HORSE, NT at New London Theatre, Alex Sims, Kathryn Ind 2010, Stage, Page of Herodias, SALOME, Headlong, Jamie Lloyd 2008, Stage, Thersites, TROILUS AND CRESSIDA, Cheek by Jowl, Declan Donnellan 2007, Stage, Pisanio, CYMBELINE, Cheek by Jowl, Declan Donnellan 2002, Stage, Lord Henry, ORIGINAL SIN, Sheffield Crucible Theatre, Peter Gill 2000, Stage, Darren, OTHER PEOPLE, Royal Court Theatre, Dominic Cooke 2000, Stage, Brian/Javid, PERA PALAS, Gate, Sacha Wares 2000, Stage, SHE STOOPS TO CONQUER, New Kent Opera, Hettie McDonald 2000, Stage, Sparkish, THE COUNTRY WIFE, Sheffield Crucible Theatre, Michael Grandage 1999, Stage, Prior, ANGELS IN AMERICA, Library, Manchester, Roger Haines 1997, Stage, Arviragus, CYMBELINE, Royal Shakespeare Company, Adrian Noble 1997, Stage, Rosencrantz, HAMLET, RSC, Matthew Warchus 1997, Stage, Balthasar, MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING, RSC, Michael Boyd 1996, Stage, -

Come up to the Lab a Sciart Special

024 on tourUK DRAMA & DANCE 2004 COME UP TO THE LAB A SCIART SPECIAL BOBBY BAKER_RANDOM DANCE_TOM SAPSFORD_CAROL BROWN_CURIOUS KIRA O’REILLY_THIRD ANGEL_BLAST THEORY_DUCKIE CHEEK BY JOWL_QUARANTINE_WEBPLAY_GREEN GINGER CIRCUS_DIARY DATES_UK FESTIVALS_COMPANY PROFILES On Tour is published bi-annually by the Performing Arts Department of the British Council. It is dedicated to bringing news and information about British drama and dance to an international audience. On Tour features articles written by leading and journalists and practitioners. Comments, questions or feedback should be sent to FEATURES [email protected] on tour 024 EditorJohn Daniel 20 ‘ALL THE WORK I DO IS UNCOMPLETED AND Assistant Editor Cathy Gomez UNFINISHED’ ART 4 Dominic Cavendish talks to Declan TheirSCI methodologies may vary wildly, but and Third Angel, whose future production, Donnellan about his latest production Performing Arts Department broadly speaking scientists and artists are Karoshi, considers the damaging effects that of Othello British Council WHAT DOES LONDON engaged in the same general pursuit: to make technology might have on human biorhythms 10 Spring Gardens SMELL LIKE? sense of the world and of our place within it. (see pages 4-7). London SW1A 2BN Louise Gray sniffs out the latest projects by Curious, In recent years, thanks, in part, to funding T +44 (0)20 7389 3010/3005 Kira O’Reilly and Third Angel Meanwhile, in the world of contemporary E [email protected] initiatives by charities like The Wellcome Trust dance, alongside Wayne McGregor, we cover www.britishcouncil.org/arts and NESTA (the National Endowment for the latest show from Carol Brown, which looks COME UP TO Science, Technology and the Arts), there’s THE LAB beyond the body to virtual reality, and Tom Drama and Dance Unit Staff 24 been a growing trend in the UK to narrow the Lyndsey Winship Sapsford, who’s exploring the effects of Director of Performing Arts THEATRE gap between arts and science professionals John Kieffer asks why UK hypnosis on his dancers (see pages 9-11). -

02 the Hollow Crown Bios

Press Contact: Harry Forbes 212.560.8027, [email protected] Lindsey Bernstein 212.560.6609, [email protected] Great Performances: The Hollow Crown Bios Tom Hiddleston After he was seen in a production of A Streetcar Named Desire by Lorraine Hamilton of the notable actors’ agency Hamilton Hodell, Tom Hiddleston was shortly thereafter given his first television role in Stephen Whittaker’s adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby (2001) for ITV, starring Charles Dance, James D’Arcy and Sophia Myles. Roles followed in two one-off television dramas co-produced by HBO and the BBC. The first was Conspiracy (2001), a film surrounding the story of the Wannsee Conference in 1942 to consolidate the decision to exterminate the Jews of Europe. The film prompted Tom’s first encounter with Kenneth Branagh who took the lead role of Heydrich. The second project came in 2002 in the critically acclaimed and Emmy Award- winning biopic of Winston Churchill The Gathering Storm, starring Albert Finney and Vanessa Redgrave. Tom played the role of Randolph Churchill, Winston’s son, and cites that particular experience – working alongside Finney and Redgrave, as well as Ronnie Barker, Tom Wilkinson, and Jim Broadbent – as extraordinary; one that changed his perspective on the art, craft and life of an actor. Tom graduated from RADA in 2005, and within a few weeks was cast as Oakley in the British independent film Unrelated by first-time director Joanna Hogg. Unrelated tells the story of a woman in her mid-40s who arrives alone at the Italian holiday home of an extended bourgeois family. -

Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Announces 2018 Next Wave

Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) announces 2018 Next Wave Festival, featuring 27 music, opera, theater, physical theater, dance, film/music, and performance art engagements, Oct 3—Dec 23 Bloomberg Philanthropies is the Season Sponsor Music/Opera Almadraba…………………… Oscar Peñas…………………………..…………………..page 3 Place…………………………. Ted Hearne, Saul Williams, Patricia McGregor………. page 6 The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane …………………………..…………………………page 6 Satyagraha…………………...Philip Glass, Tilde Björfors, Folkoperan, Cirkus Cirkör..page 17 Savage Winter…………...….. Douglas J. Cuomo, Jonathan Moore, American Opera Projects, Pittsburgh Opera……………………………… page 19 Circus: Wandering City…….. ETHEL……………………………………………………. page 22 Greek………………………… Scottish Opera/Opera Ventures, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Joe Hill-Gibbins, Jonathan Moore, Stuart Stratford….. page 28 Theater The Bacchae…………………SITI Company, Anne Bogart, Aaron Poochigian…….. .page 4 Measure for Measure………. Cheek by Jowl, Pushkin Drama Theatre, Declan Donnellan, Nick Ormerod……………………….page 9 Jack &................................... Kaneza Schaal, Cornell Alston………………………… .page 10 Falling Out…………………… Phantom Limb Company……………………………….. .page 20 The Good Swimmer…………Heidi Rodewald, Donna Di Novelli, Kevin Newbury…. .page 25 The White Album…………….Early Morning Opera, Lars Jan, Joan Didion………… .page 26 NERVOUS/SYSTEM………..Andrew Schneider………………………………………...page 32 Strange Window: The Turn of the Screw…………………. The Builders Association, Marianne Weems…………..page 33 Physical theater Humans……………………… Circa, Yaron Lifschitz……………………………………..page -

Winter's Tale by William Shakespeare

Périclès, Prince de Tyr de William Shakespeare Mise en scène – Declan Donnellan Scénographie – Nick Ormerod Suite à Ubu Roi en 2013/14/15, Declan Donnellan et Nick Ormerod reviendront à la langue française avec une création de PÉRICLÈS de Shakespeare en 2018 et 2019. Avec PÉRICLÈS, la compagnie signera sa première création de Shakespeare en langue française, pièce qui complétera son cycle des quatre 'romances tardives' de Shakespeare, après Cymbeline (2007), La tempête (2011) et Le conte d'hiver (2015). Nous sommes à la recherche de co-producteurs et de partenaires pour réaliser cette nouvelle création. Ubu Roi a été présenté pendant 34 semaines sur trois continents, et dans des villes comme Paris, Londres, New York, Moscou, Madrid et Venise. A propos d'Ubu Roi : « Donnellan obtient des interprétations sans retenue de sa troupe … le déchainement d’un champ de bataille au sein d'un univers chic et raffiné. » – The Guardian (Royaume-Uni) « Outrancière, débordente d'une énergie sans retenue » – Le Figaro (France) PÉRICLÈS, prince de Tyr PÉRICLÈS est l’une des plus étonnantes et bouleversantes des œuvres de Shakespeare. Naufragé au large de la mer méditerranée, Périclès est contraint de braver une marée de pirates, de ravisseurs et de magiciens ; de bordels, de tournois et de complots … et jusqu’à une intervention divine de la déesse Diane. Inceste, trahison, meurtre, amour et joie s’entremêlent dans ce feu d'artifice théâtral, puis, à la lumière tamisée de ses braises, Périclès retrouve sa fille Marina dans l’une des plus belles scènes que Shakespeare ait jamais écrites. Contact Eleanor Lang +44 (0) 20 7382 2353 [email protected] Declan Donnellan & Nick Ormerod Declan Donnellan forme avec Nick Ormerod la compagnie Cheek by Jowl en 1981. -

By William Shakespeare Measure for Measure Why Give

Measure for Measure by William Shakespeare Measure for Measure Why give Welcome to our 2015 season with Measure for Measure. you me this Our Russian company were last here with The Tempest and we are delighted to be back. We are particularly grateful to shame? Evgeny Pisarev and Anna Volk of the Pushkin Theatre in Moscow, without whom this production would not have been possible. Act III Scene I Thanks also to Toni Racklin, Leanne Cosby, and the entire team at the Barbican, London for their continued enthusiasm and support, and to Katy Snelling and Louise Chantal at the Oxford Playhouse. We’d also like to thank our other co-producers, Les Gémeaux/ Sceaux/Scène Nationale, in Paris, and Centro Dramático Nacional, in Madrid, as well as Arts Council England. We do hope you enjoy the show… Declan Donnellan and Nick Ormerod Petr Rykov & Company 1 2 3 Cheek by Jowl in Russia In 1986, Russian theatre director Lev Dodin of Valery Shadrin, commissioned Donnellan invited Donnellan and Ormerod to visit his and Ormerod to form their own company of company in Leningrad. Ten years later, they Russian actors in Moscow. This sister company 4 5 6 directed and designed The Winter’s Tale performs in Russia and internationally and its for the Maly Drama Theatre, which is still current repertoire includes Boris Godunov running in St. Petersburg. Throughout the by Pushkin, Twelfth Night and The Tempest 1990s the Russian Theatre Confederation by Shakespeare, and Three Sisters by Anton regularly invited Cheek by Jowl to Moscow Chekhov. Measure for Measure is Cheek as part of the Chekhov International Theatre by Jowl’s first co-production with Moscow’s Festival, and this relationship intensified in Pushkin Theatre. -

Linguaculture 1, 2014

LINGUACULTURE 1, 2014 THE HOLLOW CROWN:SHAKESPEARE, THE BBC, AND THE 2012 LONDON OLYMPICS RUTH M ORSE Université-Paris-Diderot Abstract During the summer of 2012, and to coincide with the Olympics, BBC2 broadcast a series called The Hollow Crown, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s second tetralogy of English history plays. The BBC commission was conceived as part of the Cultural Olympiad which accompanied Britain’s successful hosting of the Games that summer. I discuss the financial, technical, aesthetic, and political choices made by the production team, not only in the context of the Coalition government (and its attacks on the BBC) but also in the light of theatrical and film tradition. I argue that the inclusion or exclusion of two key scenes suggest something more complex and balanced that the usual nationalism of the plays'; rather, the four nations are contextualised to comprehend and acknowledge the regions – apropos not only in the Olympic year, but in 2014's referendum on the Union of the crowns of England/Wales and Scotland. Keywords: Shakespeare, BBC, adaptation, politics, Britishness During the summer of 2012, to coincide with the London summer Olympics, BBC2 broadcast a series called The Hollow Crown, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s second tetralogy of English history plays. An additional series, Shakespeare Unlocked, accompanied each play with a program fronted by a lead actor discussing the play and the process, illustrated by clips from the plays in which they had appeared (“The Hollow Crown”). The producer was the Neal Street Production Company in the person of Sam Mendes, a well-known stage and cinema director, celebrated not least for an Oscar for American Beauty, a rare honour for a first-time film director. -

Fantastic Tricks Before High Heaven,” Measure for Measure and Performing Triads

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU English Faculty Publications Languages and Literatures 2020 “Fantastic Tricks before High Heaven,” Measure for Measure and Performing Triads Emily Bryan Sacred Heart University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/eng_fac Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bryan, E. (2020). “Fantastic tricks before high heaven,” Measure for measure and performing triads. Religions, 11(2), 100. Doi: 10.3390/rel11020100 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Languages and Literatures at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. religions Article “Fantastic Tricks before High Heaven,” Measure for Measure and Performing Triads Emily Bryan Department of Languages and Literatures, Sacred Heart University, 5151 Park Avenue, Fairfield, CT 06825, USA; [email protected] Received: 19 January 2020; Accepted: 19 February 2020; Published: 22 February 2020 Abstract: Reading Measure for Measure through the logic of substitution has been a long-standing critical tradition; the play seems to invite topical, political, and religious parallels at every turn. What if the logic of substitution in the play goes beyond exchange and seeks out a triadic logic instead? This insistent searching for the triad appears most notably in the performance of Measure for Measure by Cheek by Jowl (2013–2019). Cheek By Jowl’s strategies of touring, simplicity, movement, and liberation create a dynamic and ever-evolving performance. -

AS and a Level Drama and Theatre

Topic Exploration Pack Practitioners: Cheek by Jowl Theatre Company Foreword by Karen Latto – OCR Subject Specialist Drama As part of our resources provision I was keen to ensure that the resources have been created by experts in Drama and in Education. For our practitioner requirement, this included resources which were made by working Theatre Makers about their own company’s practice and working methods. I would like to thank the team at Cheek by Jowl for creating this resource for OCR to support AS and A Level teachers. This resource has been created by Declan Donnellan and Nick Ormerod alongside Cheek by Jowl’s Education Officer Dominic Kennedy and talks from their perspective as working practitioners in the field of Theatre. Cheek by Jowl................................................................................................................................. 2 Repertoire .......................................................................................................................................2 Études ............................................................................................................................................5 Additional teacher preparation ......................................................................................................11 Activity 1: Études exercise ............................................................................................................12 Activity 2: Imaginary and pre-text exercise ................................................................................... -

Dossier Macbeth Arreglat

TEMPORADA ALTA 2009 – FESTIVAL DE TARDOR DE CATALUNYA GIRONA/SALT TEMPORADA ALTA 2009 – FESTIVAL DE TARDOR DE CATALUNYA GIRONA/SALT Del 1 d’octubre al 11 de desembre Cheek by Jowl MACBETH De William Shakespeare Teatre de Salt Direcció de Declan Donnellan Del 1 al 4 d’octubre DOSSIER DE PREMSA TEMPORADA ALTA 2009 – FESTIVAL DE TARDOR DE CATALUNYA GIRONA/SALT MACBETH/DONNELLAN Macbeth: Caïm sostenint, entre sorprès i aterrit, la maixella amb què acaba de matar Abel. La nit és la nit originària, la sang sembla vessar-se per primera vegada. Macbeth és la tragèdia més breu, densa i obsessiva de Shakespeare. Sense contrapunts, sense finestres, sense humor. Pocs personatges, curt període de temps, espais reduïts i tancats. Macbeth narra el naixement d’una força destructora de tal complexitat que les seves víctimes la pateixen com una epifania de l’obscuritat essencial, vessant-se sobre tot el que toquen, viuen i senten, fins a convertir les seves existències en malsons d’irrealitat i sense sentit: un conte “contat per un idiota, ple de soroll i de fúria, que no significa res”. Pitjor: un infern conscient (“Vingui el que l’ull tem veure quan succeeixi!”, proclama l’assassí), la dislocació del qual s’adverteix però no es pot reconèixer. La màquina de la Història és aquí, quintaessenciada, la màquina del Mal, de la por i de la culpa, com una malaltia maligna galopant sense fre cap a l’abisme. Més enllà de l’ambició, més enllà de la lluita pel poder, més enllà dels assassinats, més enllà dels motius. Will Keen (l’inoblidable De Flores a The changeling ) encarna el monarca escocès a la nova producció de Cheek by Jowl , dirigida per Declan Donnellan . -

In Conversation with Declan Donnellan1

Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance vol. 19 (34), 2019; http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/2083-8530.19.08 ∗ Nicole Fayard “Making Things Look Disconcertingly Different”: In Conversation with Declan Donnellan1 Abstract: In this interview acclaimed director Declan Donnellan, co-founder of the company Cheek by Jowl, discusses his experience of performing Shakespeare in Europe and the attendant themes of cultural difference, language and translation. Donnellan evokes his company’s commitment to connecting with audiences globally. He keeps returning to Shakespeare, as his theatre enables the sharing of our common humanity. It allows a flesh-and-blood carnal interchange between the actors and the audience which directly affects individuals. This interchange has significant consequences in terms of translation and direction. Keywords: Declan Donnellan; Cheek by Jowl; Shakespeare in Europe; Translation; Direction; Archetypes; Brexit. I Declan Donnellan is well-known as “one of the most original directors working in theatre today” (Le Figaro). He co-founded the company Cheek by Jowl in 1981 and is its joint Artistic Director with his life partner and the company designer, Nick Ormerod. Both artists are renowned for staging innovative productions focused on the skills of the actors and have been repeatedly acclaimed as “responsible for some of the most imaginative and revelatory classical performances [seen over the past] decades” (New York Times). They produce work in English, French and Russian and have performed in about 400 cities in fifty countries over six continents (Cheek by Jowl). Donnellan has to date directed over thirty productions, with half from the Shakespearean repertoire, such as the world-acclaimed As You Like It (1991) with Adrian Lester, performed with an all-male cast, The Winter’s Tale (Maly ∗ University of Leicester, UK.