The 1990S Timothy Walker – Alan Rickman – Russell Boulter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly June 2016

PROGRAMME THE DIVING BELL AND THE BUTTERFLY JUNE 2016 “possibly Britain’s most beautiful cinema..” (BBC) Britain’s Best Cinema – Guardian Film Awards 2014 JUNE 2016 • ISSUE 135 www.therexberkhamsted.com 01442 877759 Mon-Sat 10.30-6.30pm Sun 4.30-5.30pm BEST IN JUNE CONTENTS Films At A Glance 16-17 Rants and Pants 26-27 BOX OFFICE: 01442 877759 Mon to Sat 10.30-6.30 The Diving Bell and The Butterfly Sun 4.30-5.30 Remains one of our most powerful, beautiful films. (2008) Don’t miss. Page 18 SEAT PRICES Circle £9.00 FILMS OF THE MONTH Concessions £7.50 Table £11.00 Concessions £9.50 Royal Box Seat (Seats 6) £13.00 Whole Royal Box £73.00 All matinees £5, £6.50, £10 (box) Disabled and flat access: through SEE more. DO more. the gate on High Street (right of apartments) Truman Mustang 50% OFF YOUR SECOND PAIR A fabulous South American tragi- They’re saying this is the must-film Terms and conditions apply Director: James Hannaway comedy embracing all the worth in to see… so come and see. 01442 877999 life and death. Page 10 Page 13 Also available with Advertising: Chloe Butler 01442 877999 (From Space) Artwork: Demiurge Design 01296 668739 The Rex High Street (Three Close Lane) Berkhamsted, Herts HP4 2FG www.therexberkhamsted.com Troublemakers: Race The Story Of Land Art The timely story of Jesse Owens. “ Unhesitatingly The Rex Miss this and you might as well Hitler should have taken more 24 Bridge Street, Hemel Hempstead 25 Stoneycroft, Hemel Hempstead is the best cinema I have stop breathing… Breathtaking care of his skin. -

C. Doran Complete CV

Cailin Doran 303.956.6542 [email protected] cailindoran.com Productions Directed: Twelfth Night Watertown Children’s Theatre 2020 Who is Eartha Mae? Bridge Repertory Theater 2019 Oklahoma! Voices Boston 2018 Shakespeare in Love (AD) Speakeasy Stage 2018 Pirates of Penzance Voices Boston 2017 Yeomen of the Guard MIT Gilbert and Sullivan Players 2017 Hamlet (AD) Boston Theatre Company 2017 Midsummer Night’s Dream (AD) Boston Theatre Company 2017 Major Roles Performed: Complete Performance Resume available upon request. Music Theatre: Laurey Williams, Oklahoma! | Cinderella, Into the Woods | Kate, The Wild Party (LaChiusa) | The Old Woman, Candide Shakespeare: Beatrice, Much Ado About Nothing | Desdemona Othello Teaching Experience: Voices Boston - Guest Artist - resident Theatre Teacher and Director - Developed workshops and lectures for Laban based movement classes and Acting Fundamentals rooted in Stanislavski and Meisner traditions - Collaborated with Artistic Director, Executive Director, Music Director, Technical Director and Board to produce yearly main stage productions - Generated pre-production dramaturgical lecture series to elucidate the historical context and influences on and of "Oklahoma!" - Participated in best practices convocations for the growth of students and the organizations outreach The Boston Conservatory - Teacher’s Assistant - As Doug Lockwood’s TA, attended and observed undergraduate Acting 1, leading Declan Donnellan based exercises and scene study of contemporary texts -

Harrison Ford 5 Film Collection

Page 1 HARRISON FORD 5 FILM COLLECTION TM Available on DVD & Bluray from 2nd November Includes: Firewall, 42, Presumed Innocent, Frantic and The Fugitive On November 2nd 2015, Warner Bros. Home Entertainment (WBHE) will release the Harrison Ford 5 Film Collection, three of which are brand new to Bluray. ABOUT THE FILMS 42 (2013) Written and directed by Brian Helgeland (Legend, LA Confidential) this is the inspiring true story of the man who broke the Major League baseball colour barrier, Jackie Robinson, with Ford starring as the man who signed him, Branch Rickey. Firewall (2006) Ford proved he still had what it takes in the action man genre in this dazzling technothriller, starring as a security specialist forced to rob a bank after his family is taken hostage by the dastardly Paul Bettany. Frantic (1988) Directed by Roman Polanski, this superb thriller, a forerunner to the Liam Neeson Taken films, sees Harrison Ford as a doctor whose wife disappears from their hotel room during a trip to Paris. What follows is a nightmarish journey into the underbelly of the city as Ford attempts to find out Page 2 what has happened to her. Presumed Innocent (1990) A sensational nailbiting whodunnit right up to the final scene, this box office smash was based on the bestselling Scott Turow novel, and directed by the great Alan J Pakula (Klute). Ford is a DA who is put in charge of the investigation of his lover’s murder – and finds himself in the frame for the killing. When the film was released it became the ‘don’t reveal the ending’ hit of the year. -

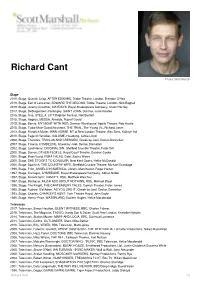

Richard Cant

Richard Cant Photo: Wolf Marloh Stage 2019, Stage, Quentin Crisp, AFTER EDWARD, Globe Theatre, London, Brendan O'Hea 2019, Stage, Earl of Lancaster, EDWARD THE SECOND, Globe Theatre, London, Nick Bagnall 2018, Stage, Jeremy Crowther, MAYDAYS, Royal Shakespeare Company, Owen Horsley 2017, Stage, DeStogumber/ Poulengey, SAINT JOAN, Donmar, Josie Rourke 2016, Stage, One, STELLA, LIFT/Brighton Festival, Neil Bartlett 2015, Stage, Aegeus, MEDEA, Almeida, Rupert Goold 2015, Stage, Bernie, MY NIGHT WITH REG, Donmar Warehouse/ Apollo Theatre, Rob Hastie 2015, Stage, Tudor/Male Guard/Assistant, THE TRIAL, The Young Vic, Richard Jones 2013, Stage, Friedrich Muller, WAR HORSE, NT at New London Theatre, Alex Sims, Kathryn Ind 2010, Stage, Page of Herodias, SALOME, Headlong, Jamie Lloyd 2008, Stage, Thersites, TROILUS AND CRESSIDA, Cheek by Jowl, Declan Donnellan 2007, Stage, Pisanio, CYMBELINE, Cheek by Jowl, Declan Donnellan 2002, Stage, Lord Henry, ORIGINAL SIN, Sheffield Crucible Theatre, Peter Gill 2000, Stage, Darren, OTHER PEOPLE, Royal Court Theatre, Dominic Cooke 2000, Stage, Brian/Javid, PERA PALAS, Gate, Sacha Wares 2000, Stage, SHE STOOPS TO CONQUER, New Kent Opera, Hettie McDonald 2000, Stage, Sparkish, THE COUNTRY WIFE, Sheffield Crucible Theatre, Michael Grandage 1999, Stage, Prior, ANGELS IN AMERICA, Library, Manchester, Roger Haines 1997, Stage, Arviragus, CYMBELINE, Royal Shakespeare Company, Adrian Noble 1997, Stage, Rosencrantz, HAMLET, RSC, Matthew Warchus 1997, Stage, Balthasar, MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING, RSC, Michael Boyd 1996, Stage, -

FILMS and THEIR STARS 1. CK: OW Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 2

FILMS AND THEIR STARS 1. CK: OW Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 2. TGTBATU: CE The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Clint Eastwood 3. RFTS: KM Reach for the Sky: Kenneth More 4. FG; TH Forest Gump: Tom Hanks 5. TGE: SM/CB The Great Escape: Steve McQueen and Charles Bronson ( OK. I got it wrong!) 6. TS: PN/RR The Sting: Paul Newman and Robert Redford 7. GWTW: VL Gone with the Wind: Vivien Leigh 8. MOTOE: PU Murder on the Orient Express; Peter Ustinov (but it wasn’t it was Albert Finney! DOTN would be correct) 9. D: TH/HS/KB Dunkirk: Tom Hardy, Harry Styles, Kenneth Branagh 10. HN: GC High Noon: Gary Cooper 11. TS: JN The Shining: Jack Nicholson 12. G: BK Gandhi: Ben Kingsley 13. A: NK/HJ Australia: Nicole Kidman, Hugh Jackman 14. OGP: HF On Golden Pond: Henry Fonda 15. TDD: LM/CB/TS The Dirty Dozen: Lee Marvin, Charles Bronson, Telly Savalas 16. A: MC Alfie: Michael Caine 17. TDH: RDN The Deer Hunter: Robert De Niro 18. GWCTD: ST/SP Guess who’s coming to Dinner: Spencer Tracy, Sidney Poitier 19. TKS: CF The King’s Speech: Colin Firth 20. LOA: POT/OS Lawrence of Arabia: Peter O’Toole, Omar Shariff 21. C: ET/RB Cleopatra: Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton 22. MC: JV/DH Midnight Cowboy: Jon Voight, Dustin Hoffman 23. P: AP/JL Psycho: Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh 24. TG: JW True Grit: John Wayne 25. TEHL: DS The Eagle has landed: Donald Sutherland. 26. SLIH: MM Some like it Hot: Marilyn Monroe 27. -

June Movies at 6 Pm

JUNE MOVIES AT 6 PM Thurs Jun 3 – I Confess A priest, who comes under suspicion for murder, cannot clear his name without breaking the seal of the confessional. Montgomery Clift, Anne Baxter, Karl Malden, 95min, 1953, NR Fri Jun 4 – Men Of Honor The story of Carl Brashear, the first African-American U.S. Navy Diver, and the man who trained him. Cuba Gooding Jr., Robert De Niro, Charlize Theron, 129min, 2000, R Sat Jun 5 – To Kill A Mocking Bird Atticus Finch, a lawyer in the Depression-era South, defends a black man against an undeserved rape charge, and his children against prejudice. Gregory Peck, John Megna, Frank Overton, 129min, 1962, NR Sun Jun 6 – The Longest Day The events of D-Day, told on a grand scale from both the Allied and German points of view. John Wayne, Robert Ryan, Richard Burton, 172min, 1962, G Thurs Jun 10 – The Irishman An old man recalls his time painting houses for his friend, Jimmy Hoffa, through the 1950-70s. Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Joe Pesci, 209min, 2019, R Fri Jun 11 – Die Hard An NYPD officer tries to save his wife and several others taken hostage by German terrorists during a Christmas party at the Nakatomi Plaza in Los Angeles. Bruce Willis, Alan Rickman, Bonnie Bedelia, 132min, 1988, R Sat Jun 12 – Buck Privates Two sidewalk salesman enlist in the army in order to avoid jail, only to find that their drill instructor is the police officer who tried having them imprisoned. Bud Abbott, Lou Costello, Lee Bowman, 84min, 1941, NR Sun Jun 13 – In A Lonely Place A potentially violent screenwriter is a murder suspect until his lovely neighbor clears him. -

Organisations Alexandra Theatre, Bognor Regis

Statement from (in alphabetical order) Organisations Alexandra Theatre, Bognor Regis - Hazel Latus Almeida Theatre – Rupert Goold, Denise Wood Ambassador Theatre Group - Mark Cornell and Michael Lynas Andrew Treagus Associates - Andrew Treagus Arcola Theatre – Mehmet Ergen, Leyla Nazli, Ben Todd Arts Theatre - Louis Hartshorn and Lizzie Scott Barbican Theatre - Toni Racklin Battersea Arts Centre – David Jubb Belgrade Theatre – Hamish Glen, Joanna Reid Birmingham Hippodrome - Fiona Allan Birmingham Repertory Theatre – Roxana Silbert and Stuart Rogers Birmingham Stage Company - Neal Foster and Louise Eltringham Bridge Theatre – Nicholas Hytner, Nick Starr Bristol Old Vic – Tom Morris, Emma Stenning Bush Theatre – Madani Younis, Jon Gilchrist Cheek by Jowl - Declan Donnellan, Nick Ormerod and Eleanor Lang Chichester Festival Theatre – Daniel Evans, Rachel Tackley Citizens Theatre - Dominic Hill, Judith Kilvington Curve Theatre - Chris Stafford and Nikolai Foster Darlington Hippodrome - Lynda Winstanley Derby Theatre – Sarah Brigham Disney Theatrical Productions - Richard Oriel and Fiona Thomas Donmar Warehouse – Josie Rourke, Kate Pakenham Donna Munday Arts Management - Donna Munday D'Oyly Carte Opera Trust - Ian Martin Eclipse - Dawn Walton Empire Street Productions - James Bierman English National Ballet - Tamara Rojo & Patrick Harrison English Touring Theatre - Richard Twyman, Sophie Watson Everyman Theatre, Cheltenham - Paul Milton and Penny Harrison Festival City Theatres Trust - Duncan Hendry and Brian Loudon Fit The Bill - Martin Blore -

Alan Rickman, the British Actor Who Played The

Alan Rickman, the British actor who played the multifaceted Professor Severus Snape in “Harry Potter” and villain Hans Gruber in “Die Hard” has passed away at the age of 69. He was pronounced dead last Thursday after battling cancer. The news came as a shock to many. I know I was shocked. This was the first thing I saw when I log onto my Facebook account that morning. Not a great way to start my day. Celebrities expressed their sadness on the news. J.K. Rowling author of the Harry Potter series expressed her sadness through Twitter. When asked how she felt, “There are no words to express how shocked and devastated I am to hear of Alan Rickman’s death. Fans had lost “a great talent” and his family “have lost a part of their hearts.” Daniel Radcliffe who played the titular character Harry Potter, said Rickman was kind and generous ,“Alan was extremely kind, generous, self-deprecating and funny,” he wrote on Google+. Like many actors he has never been nominated for an Oscar despite being a critically acclaimed actor. His true love may have been stage acting but I’ll always think of him as Professor Snape, the antagonistic professor who played a major role in Harry’s life behind the scenes. He took on the role only have read three books up to that point. Because of this he did know how much of a good guy Snape was. Rickman is survived by his wife Rima Horton whom he had been together with since 1965. They met as teenager and they have been together ever since. -

Come up to the Lab a Sciart Special

024 on tourUK DRAMA & DANCE 2004 COME UP TO THE LAB A SCIART SPECIAL BOBBY BAKER_RANDOM DANCE_TOM SAPSFORD_CAROL BROWN_CURIOUS KIRA O’REILLY_THIRD ANGEL_BLAST THEORY_DUCKIE CHEEK BY JOWL_QUARANTINE_WEBPLAY_GREEN GINGER CIRCUS_DIARY DATES_UK FESTIVALS_COMPANY PROFILES On Tour is published bi-annually by the Performing Arts Department of the British Council. It is dedicated to bringing news and information about British drama and dance to an international audience. On Tour features articles written by leading and journalists and practitioners. Comments, questions or feedback should be sent to FEATURES [email protected] on tour 024 EditorJohn Daniel 20 ‘ALL THE WORK I DO IS UNCOMPLETED AND Assistant Editor Cathy Gomez UNFINISHED’ ART 4 Dominic Cavendish talks to Declan TheirSCI methodologies may vary wildly, but and Third Angel, whose future production, Donnellan about his latest production Performing Arts Department broadly speaking scientists and artists are Karoshi, considers the damaging effects that of Othello British Council WHAT DOES LONDON engaged in the same general pursuit: to make technology might have on human biorhythms 10 Spring Gardens SMELL LIKE? sense of the world and of our place within it. (see pages 4-7). London SW1A 2BN Louise Gray sniffs out the latest projects by Curious, In recent years, thanks, in part, to funding T +44 (0)20 7389 3010/3005 Kira O’Reilly and Third Angel Meanwhile, in the world of contemporary E [email protected] initiatives by charities like The Wellcome Trust dance, alongside Wayne McGregor, we cover www.britishcouncil.org/arts and NESTA (the National Endowment for the latest show from Carol Brown, which looks COME UP TO Science, Technology and the Arts), there’s THE LAB beyond the body to virtual reality, and Tom Drama and Dance Unit Staff 24 been a growing trend in the UK to narrow the Lyndsey Winship Sapsford, who’s exploring the effects of Director of Performing Arts THEATRE gap between arts and science professionals John Kieffer asks why UK hypnosis on his dancers (see pages 9-11). -

02 the Hollow Crown Bios

Press Contact: Harry Forbes 212.560.8027, [email protected] Lindsey Bernstein 212.560.6609, [email protected] Great Performances: The Hollow Crown Bios Tom Hiddleston After he was seen in a production of A Streetcar Named Desire by Lorraine Hamilton of the notable actors’ agency Hamilton Hodell, Tom Hiddleston was shortly thereafter given his first television role in Stephen Whittaker’s adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby (2001) for ITV, starring Charles Dance, James D’Arcy and Sophia Myles. Roles followed in two one-off television dramas co-produced by HBO and the BBC. The first was Conspiracy (2001), a film surrounding the story of the Wannsee Conference in 1942 to consolidate the decision to exterminate the Jews of Europe. The film prompted Tom’s first encounter with Kenneth Branagh who took the lead role of Heydrich. The second project came in 2002 in the critically acclaimed and Emmy Award- winning biopic of Winston Churchill The Gathering Storm, starring Albert Finney and Vanessa Redgrave. Tom played the role of Randolph Churchill, Winston’s son, and cites that particular experience – working alongside Finney and Redgrave, as well as Ronnie Barker, Tom Wilkinson, and Jim Broadbent – as extraordinary; one that changed his perspective on the art, craft and life of an actor. Tom graduated from RADA in 2005, and within a few weeks was cast as Oakley in the British independent film Unrelated by first-time director Joanna Hogg. Unrelated tells the story of a woman in her mid-40s who arrives alone at the Italian holiday home of an extended bourgeois family.