Pentecost 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 30, 2019

June 30, 2019 TIME FOR ORDINARY! and the Solemnity of St Peter and St Paul Apostles (always on June 29, and falling this Saturday). I have said many times that there is nothing Time for ordinary!! Last week, I wrote to you about “time for a "ordinary" about "Ordinary Time". The word "ordinary" comes from the change" the longest-ever column I wrote in my nearly nine years at Latin word "ordo”, which simply means "order". "Ordinary Time" in our OLHOC (out of a total of about 450 columns from mid-September 2010 till Annual Liturgical Cycle is simply the 34 weeks that occur every year outside now). Yes, there is a time for change and a time for stability, in the same of the four Liturgical Seasons: Advent (four weeks before Christmas Day), way there is a time for happiness and a time for sorrow. God is in charge, we Christmas (the weeks following Christmas Day until the Solemnity of the are not! Some of you have told me that they found it difficult to read the Baptism of the Lord), varying in length depending on the calendar Lent, and written text in the weekly bulletin, as it was typed with the smallest possible Easter (50 days until Pentecost). font to fit into one single, full page. And the only excuse I can make for such a long column is that I did not have time to make it shorter. I am in good We all love the four natural Seasons we have in Waldorf.. They provide a company. -

Calendars from Around the World

Calendars from around the world Written by Alan Longstaff © National Maritime Museum 2005 - Contents - Introduction The astronomical basis of calendars Day Months Years Types of calendar Solar Lunar Luni-solar Sidereal Calendars in history Egypt Megalith culture Mesopotamia Ancient China Republican Rome Julian calendar Medieval Christian calendar Gregorian calendar Calendars today Gregorian Hebrew Islamic Indian Chinese Appendices Appendix 1 - Mean solar day Appendix 2 - Why the sidereal year is not the same length as the tropical year Appendix 3 - Factors affecting the visibility of the new crescent Moon Appendix 4 - Standstills Appendix 5 - Mean solar year - Introduction - All human societies have developed ways to determine the length of the year, when the year should begin, and how to divide the year into manageable units of time, such as months, weeks and days. Many systems for doing this – calendars – have been adopted throughout history. About 40 remain in use today. We cannot know when our ancestors first noted the cyclical events in the heavens that govern our sense of passing time. We have proof that Palaeolithic people thought about and recorded the astronomical cycles that give us our modern calendars. For example, a 30,000 year-old animal bone with gouged symbols resembling the phases of the Moon was discovered in France. It is difficult for many of us to imagine how much more important the cycles of the days, months and seasons must have been for people in the past than today. Most of us never experience the true darkness of night, notice the phases of the Moon or feel the full impact of the seasons. -

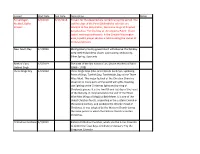

Subject Start Date End Date Description Notes Farvardegan, 8/8/2018 8/17/2018 Prayers for the Departed Are Recited During the Period

Subject Start Date End Date Description Notes Farvardegan, 8/8/2018 8/17/2018 Prayers for the departed are recited during the period. The Muktad, Gatha last five days of the Parsi (Shahnshahi) calendar are Prayers devoted to five Holy Gathas, the divine songs of Prophet Zarathushtra. The final day of the period is Pateti - (from ‘patet’ meaning confession). In the Greater Washington area, a public prayer service is held invoking the names of deceased persons. New Year's Day 1/1/2019 Montgomery County government will observe this holiday. Area: Bethesda/Chevy Chase, East County, MidCounty, Silver Spring, Upcounty Birth of Guru 1/5/2019 The birth of the last human Guru (divine teacher) of Sikhs Gobind Singh (1666 - 1708) Three Kings Day 1/6/2019 Three Kings Days (also called Dia de los Reyes, Epiphany, Feast of Kings, Twelfth Day, Twelfthtide, Day of the Three Wise Men). This major festival of the Christian Church is observed in many parts of the world with gifts, feasting, last lighting of the Christmas lights and burning of Christmas greens. It is the Twelfth and last day of the Feast of the Nativity. It commemorates the visit of the Three Wise Men (Kings of Magi) to Bethlehem. It is one of the oldest Christian feasts, originating in the Eastern Church in the second century, and predates the Western feast of Christmas. It was adopted by the Western Church during the same period in which the Eastern Church accepted Christmas. Orthodox Christmas 1/7/2019 Eastern Orthodox Churches, which use the Julian Calendar to determine feast days, celebrate on January 7 by the Gregorian Calendar. -

Religious Dates and Festivals 2018-2019 Rosh Hashanah

Religious Dates and Festivals 2018-2019 SEPTEMBER 29-OCTOBER 1, 2019 Rosh Hashanah (Judaism) Rosh Hashanah occurs on the first and second days of Tishri. In Hebrew, Rosh Hashanah means, literally, "head of the year" or "first of the year." Rosh Hashanah is commonly known as the Jewish New Year. This name is somewhat deceptive, because there is little similarity between Rosh Hashanah, one of the holiest days of the year, and the American midnight drinking bash and daytime football game. There is, however, one important similarity between the Jewish New Year and the American one: Many Americans use the New Year as a time to plan a better life, making "resolutions." Likewise, the Jewish New Year is a time to begin introspection, looking back at the mistakes of the past year and planning the changes to make in the new year. No work is permitted on Rosh Hashanah. Much of the day is spent in synagogue, where the regular daily liturgy is somewhat expanded. In fact, there is a special prayerbook called the machzor used for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur because of the extensive liturgical changes for these holidays. The common greeting at this time is L'shanah tovah ("for a good year"). This is a shortening of "L'shanah tovah tikatev v'taihatem" (or to women, "L'shanah tovah tikatevi v'taihatemi"), which means "May you be inscribed and sealed for a good year." OCTOBER 8-9, 2019 Yom Kippur (Judaism) IPA: [ jɔm ki pur]), also known in English as the Day of ,יוֹם כִּ פּוּר :Yom Kippur (Hebrew Atonement, is the most solemn and important of the Jewish holidays. -

Why Is Green the Color of Ordinary Time?

Because the term ordinary in English most often means something that's not special or distinctive, many people think that Ordinary Time refers to parts of the calendar of the Catholic Church that are unimportant. Even though the season of Ordinary Time makes up most of the liturgical year in the Catholic Church, the fact that Ordinary Time refers to those periods that fall outside of the major liturgical seasons reinforces this impression. Yet Ordinary Time is far from unimportant or uninteresting. Why Is Ordinary Time Called Ordinary? Ordinary Time is called "ordinary" not because it is common but simply because the weeks of Ordinary Time are numbered. The Latin word ordinals, which refers to numbers in a series, stems from the Latin word ordo, from which we get the English word order. Thus, the numbered weeks of Ordinary Time, in fact, represent the ordered life of the Church—the period in which we live our lives neither in feasting (as in the Christmas and Easter seasons) or in more severe penance (as in Advent and Lent), but in watchfulness and expectation of the Second Coming of Christ. It's appropriate, therefore, that the Gospel for the Second Sunday of Ordinary Time (which is actually the first Sunday celebrated in Ordinary Time) always features either John the Baptist's acknowledgment of Christ as the Lamb of God or Christ's first miracle—the transformation of water into wine at the wedding at Cana. Thus, for Catholics, Ordinary Time is the part of the year in which Christ, the Lamb of God, walks among us and transforms our lives. -

Exciting Events & Promotions

Exciting Events & Promotions Dubbed the “Events Capital of Asia”, Hong Kong is famous for its action-packed calendar filled with exciting E happenings year-round. In 2017/18, we not only organised and supported over 90 events in town, but also came up xciting with new campaigns to give visitors an authentic experience of Hong Kong. E vents & P © Topaz Leung © Lee Wai-san romotions Old Town Central Hong Kong Chinese New Year Hong Kong Arts Month Celebrations Hong Kong Summer Fun Hong Kong Dragon Boat Carnival e-Sports and Music Festival Hong Kong Hong Kong Cyclothon Hong Kong Wine & Dine Festival Hong Kong WinterFest Hong Kong New Year Countdown Hong Kong Pulse Light Show A Symphony of Lights Celebrations Great Outdoors Hong Kong Supporting other events Strategic Initiatives Hong Kong Tourism Board Annual Report 2017/18 43 Hong Kong Neighbourhoods - Old Town Central Much of Hong Kong’s charm lies in the unique local culture and in the everyday life of the people. To bring visitors closer to the heartbeat of this pulsating city, the HKTB put together an original promotion called “Hong Kong Neighbourhoods”, with a view to expanding visitors’ footprint, inviting them to go beyond the traditional areas to explore the local communities, and extending their stay in Hong Kong. launched in April 2017, Old Town Central (OTC) was the first district promoted under “Hong Kong Neighbourhoods”. Five walking routes, highlighting historical architecture and landmarks, arts and culture, dining outlets and lifestyle boutiques, were designed to refresh visitors’ perspective of Central and Sheung Wan. In addition to working with our trade partners to promote the guided tours, we collaborated with local celebrities and long-time expatriates to unveil the district’s genuine charm and hidden gems through public relations campaigns as well as digital and social platforms. -

What Is Lent

LENT through to EASTER Ash Wednesday is a day of solemn remembrance when we Advent tells us Christ is near, Christmas tells us He is here. are reminded that death is coming “Ashes to ashes.” The In Epiphany we trace all the stories of his grace. ashes are derived from the palms of the previous Palm Candlemas doth then appear, telling that our Lent is near. Sunday. Soon we look for a new moon, Wednesday next we fast till noon. Ashes on our brows appear, mindful that an end is near. Palm Sunday is the preceding Sunday before Easter and Forty days with Sundays off brings us to the One they scoff. marks the beginning of Holy Week – the last week of Jesus’ life – and heralds the entrance of Jesus into Jerusalem. The Lent is a solemn religious observance in the week is marked by several solemn days. Christian liturgical calendar that begins on Ash Wednesday and ends 40 days later (not counting Sundays) Maundy Thursday "Maundy" comes from the Latin on Easter Sunday. word mandatum, or commandment, reflecting Jesus' words Traditionally, the purpose of Lent is the preparation of the "I give you a new commandment." It is usually marked by believer for Easter through prayer, one of two events – Washing of Feet or the remembrance doing penance, mortifying the flesh, repentance of of the Institution of the Lord’s Supper. sins, almsgiving, and self-denial. Good Friday is the day we commemorate the crucifixion The 40 days of Lent are reminiscent of the 40 days Jesus and death of Jesus. -

26 January 2020 the General Roman Calendar Special Indulgences, Days of Devotion, and Other Information That May Be Convenient for the Clergy to Know

26 January 2020 The General Roman Calendar special indulgences, days of devotion, and other information that may be convenient for the clergy to know. The Ordo is “Throughout the course of the year the Church unfolds the issued with the authority of the bishop or bishops concerned, entire mystery of Christ and observes the birthdays of the and is binding on the clergy in their jurisdiction. Saints.” Universal Norms on the Liturgical Year and the Calendar The calendar of the Roman Missal and Roman Breviary, apart from special privilege, always forms the basis of The Church Year, which begins each year on the First the Ordo recitandi. To this the feasts celebrated in the Sunday of Advent and ends the week following the Feast diocese are added, and, as the higher grade of these special of Christ the King, combines two cycles of liturgical celebrations often causes them to take precedence of those in celebrations. One is called the Proper of Time or the ordinary calendar, a certain amount of shifting and Temporale, associated with the moveable date of Easter and transposition is inevitable, even apart from the complications the fixed date of Christmas. The other is associated with caused by the movable feasts. All this must be calculated and fixed calendar dates and has been called the Proper of arranged beforehand in accordance with the rules of the Saints or Sanctorale. general rubrics of the Missal and Breviary. Even so, the In the Temporale, the most important moveable feast on clergy of particular churches must further provide for the the calendar is Easter. -

Telling Time in the Church Year Cycle the Church Year Cycle

Telling Time in the Church Year Cycle The Church Year Cycle Telling Time in the Church Year Cycle provides historical 1. Advent backgrounds, meanings and reflections for the seasons in our 2. Christmas Eve church year. 3. Christmas Day These pages may be copied and cut for use in bulletins, 4. Christmas Season newsletters and Christian Education programs. 5. Epiphany You have permission to copy this document in whole or in 6. Transfiguration part for congregational use. 7. Lent 8. Palm/Passion Sunday 9. Maundy Thursday 10. Good Friday 11. Easter Day 12. Easter Season 13. Pentecost Day 14. Pentecost Season 15. Trinity Sunday 16. The Reign of Christ Sunday © The Presbyterian Church in Canada, 2007 A Time Called … ADVENT A Time Called … CHRISTMAS EVE When children say, “I can’t wait for Christmas,” they convey what it means The stores are closed. There are only a few things left to do. The children to live in Advent. With joy they are waiting for an event that is good, that has have to wait for just one more sleep. At last, we can give ourselves over to been promised, and is now hidden from sight. Children do manage to wait. the mystery of it all and let the carols, the church, and the story speak to us One way they do this is by sharing in the many preparations for Christmas. again. What is the meaning of Waiting and preparing are the themes of Advent for adults as well. But when Christmas Eve? did Advent begin? And what can it mean in your life? Historical Roots of Christmas Eve Historical Roots of Advent No one knows when this service The calendar year may begin on January 1, but for Christians the came into being. -

David Carvajal Casal Lent

Lent David Carvajal Casal Lent Liturgical Season from Ash Wednesday to Palm Sunday “Then, speaking to all, he said, 'If anyone wants to be a follower of mine, let him renounce himself and take up his cross every day and follow me.” (Lk. 9:23) Lent: • One of the five Liturgical Seasons. • A Germanic word simply meaning Spring, or Springtime. • Springtime is a time for CHANGE and RENEWAL after death during the winter. • A call to conversion, and a preparation for catechumens. • One of the five liturgical seasons. • There are three elements: Recalling of Baptism, Prayer, and Penance. • Some hold the attitude that, “First comes the feast, then comes the hangover,” while the Catholic attitude is, "First comes the fast, then comes the feast.” • Since Easter is the most important holy day for Christians, the faithful engage in 40 days of fasting and penance to prepare for this event. Lent in the Bible Then Jesus was led by the Spirit into the desert to be tested by the devil. He fasted for forty days and forty nights, and afterwards he was hungry.” (Mt. 4:1-2) "I turned to the Lord God, pleading in earnest prayer, with fasting, sackcloth and ashes“ (Dn 9:3). 11 All the Israelites in Jerusalem, including women and children, lay prostrate in front of the Temple, and with ashes on their heads stretched out their hands before the Lord. 12 They draped the altar itself in sackcloth and fervently joined together in begging the God of Israel not to let their children be carried off, their wives distributed as booty, the towns of their heritage destroyed, the Temple profaned and desecrated for the heathen to gloat over. -

Hemingway's a Moveable Feast

HEMINGWAY’S A MOVEABLE FEAST: MASKED THEMES IN THE CONTEXT OF HIS LIFE by Katherine E. Witt, B.S. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Literature December 2015 Committee Members: Allan R. Chavkin, Chair Victoria Smith Graeme Wend-Walker COPYRIGHT by Katherine E. Witt 2015 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of the material for financial gain without the author’s express is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Katherine E. Witt, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the English Department Faculty at the United States Air Force Academy for introducing me to the world of literature and encouraging me to pursue a subject that I love. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the members of my thesis committee, Allan Chavkin, Victoria Smith, and Graeme Wend-Walker, for their invaluable insight. I also wish to express appreciation to my family and work supervisors for allowing the time to perform my research and pursue my academic goals. Finally, I wish to thank my professors at Texas State University for their substantial contribution in making my graduate study a memorable experience. -

Calendars and Feast Days in Scandinavia Fritz Juengling Ph.D., AG®

Calendars and Feast Days in Scandinavia Fritz Juengling Ph.D., AG® The Julian and Gregorian calendars The Julian calendar had been in use for centuries. It was introduced in 46 BC by Julius Caesar. A leap day was added to February every fourth year= 365.25 days. That is too long. The year is 365.2425 days. The year, especially Easter, which is tied to the vernal equinox, was getting ‘off.’ In 1582, the calendar was off by 10 days. Pope Gregory XIII commissioned a reform to correct the aberration. Catholic countries, including France and parts of the Low Countries and Germany, adopted the Gregorian calendar right away, usually 1582 or 1583. Non- Catholic areas were slow to follow. Denmark and Norway switched in 1700, where Sweden did not finally do so until 1753, although it had begun to do so in 1700. Sweden’s change from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar is a complicated one. Sweden decided to switch beginning in 1700, but only by eliminating leap years until the change would be complete in 1740. During this 40-year period, the Swedish calendar would be off from every other calendar in the world. The leap day was omitted in 1700, but, surprisingly, not in 1704 or 1708. In 1712, the King recognized the problem and decided to make a change—back to the Julian calendar! So, the day that was omitted in 1700 was restored in 1712 and Sweden has the ignominious distinction of having 30 days in February for one year, 1712. Finland follows Sweden in this respect, as it was under Swedish rule at the time.