Undergraduate Dissertation Trabajo Fin De Grado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGE NO. TITLE ACTORS 12 6140 2012 J.Cusack/A.Peet/T.Newton 12

AGE NO. TITLE ACTORS 12 6140 2012 J.Cusack/A.Peet/T.Newton 12 7072 Insurgent S.Woodley/K.Winslet/T.James U 6575 Monster in Paris 15 7102 "71 J.O'Connell 12 5025 10 Things I Hate about You 12 5025 10 Things I Hate about You 12 6713 10 Years -The Reunion- L.Collins/R.Dawson/J.Dewan-Tatum/B.Geraghty 12 5907 10.000 BC S.Strait/C.Belle/C.Curtis U 6336 101 Dalmatians II -Disney- 15 6997 12 Years a Slave C.Ejiofor/M.Fassbender/B.Cumberbatch 15 6383 127 Hours J.Franco/A.Tamblyn/K.Mara 12 5195 13 Going on 30 15 7112 13 Minutes (Elser) C.Friedel/K.Schütter/B.Klausner/J.Von Bülow Oliver Hirschbiegel 15 5011 13th Warrior 15 5799 1408 -S.King- J.Cusack/S.L.Jackson 12 5570 16 Blocks 12 6027 17 Again Z.Efron/L.Mann/T.Lennon/M.Trachtenberg 15 6641 2 Days in New York J.Delpy/C.Rock 12 6965 20 Feet From Stardom U 5188 20.000 Leagues under the Sea -Jules Verne- 15 6735 21 Days:The Eineken Kidnapping R.Hauer 15 6621 21 Jump Street J.Hill/C.Tatum 12 5848 27 Dressed K.Heigl/J.MarsdonM.Akerman 18 5070 28 Days Later 15 6850 2Guns D.Washington/M.Wahlberg 12 7020 3 Days to Kill K.Costner/A.Heard/H.Steinfeld 15 5812 3:10 too Yuma R.Crowe/C.Bale 15 6646 388 Arletta Avenue N.Stahl/M.Kirsher 15 6238 4.3.2.1 E.Roberts/T.Egerton/O.Lovibond/S.Warren-Markland 12 6942 42 -the True Story of a Sprots Legend C.Boseman/H.Ford 15 6429 5 Days of War R.Friend/E.Chirqui/V.Kilmer/A.Garcia 15 6537 50/50 J.Gordon-Levitt/S.Rogen/B.Dallas Howard/A.Kendrick 12 6099 500 Days of Summer J.Gordon-Levitt/Z.Deschanel 15 5075 8 Mile 15 6796 A Good Day to Die Hard B.Willis/J.Courtney/S.Koch -

Have a Available ‘Wonderful’ Holiday

NEW LOCATION SAME GREAT DEALS 1600 S. Main St. Ned’s Pawn Laurinburg, NC 28352 December 21 - 27, 2019 JEWELRY • AUDIO (910) 276-5310 Jimmy Stewart and Donna Reed star in “It’s a Wonderful Life” Refer a friend programs Have a available ‘Wonderful’ holiday 910 276 7474 | 877 829 2515 12780 S Caledonia Rd, Laurinburg, NC 28352 Joy Locklear, Store Manager 234 E. Church Street, Laurinburg NC 910-277-8588 www.kimbrells.com Page 2 — Saturday, December 21, 2019 — Laurinburg Exchange “Serving Scotland A holiday classic with class: County 38 years” Danny Caddell, Agent Jimmy Stewart stars in ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ 915 S Main Street The Oaks Professional Building PageLaurinburg, 2 — Saturday, NC 28352 December 21, 2019 — Laurinburg Exchange Bus: 910-276-3050 [email protected] A holiday classic with class: Thank you for your loyalty. We appreciate you. Jimmy Stewart stars in ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ The personal attention from Diana Graves, Debbie Barnes, Laura Haywood, Gail Jackson and Danny Caddell given at the time of purchase and when the unexpected happens, sets them apart from other providers. FOR NEW ACCOUNTS UP SAVE TO $100 ON YOUR FIRST IN-STORE PURCHASE* when you open and use a new Lowe’s Advantage Card. Minimum purchase required. Offer ends 2/1/20. *Cannot be combined with any other offer. Coupon required. Lowe's of Laurinburg By Kyla910 Brewer US 15-401 By-Pass |Reed, Laurinburg, “From Here NC to28352 Eternity,” TV Media 1953). (910) 610-2365Karolyn Grimes (“The Bishop’s he holiday favorite that never Wife,” 1947), who played George TByfails Kyla to Brewer warm viewers’ hearts is andReed, Mary’s “From daughter Here to Eternity,” Zuzu, is one backTV Media just in time for Christmas of1953). -

The Voice-Over

CINEPHILE The University of British Table of Contents Columbia’s Film Journal Vol. 8 No. 1 Spring 2012 Editor’s Note 2 “The Voice-Over” Contributors 3 ISSN: 1712-9265 About a Clueless Boy and Girl: Voice-Over in Romantic 5 Copyright and Publisher Comedy Today The University of British Sarah Kozloff Columbia Film Program What Does God Hear? Terrence Malick, Voice-Over, and 15 Editor-in-Chief The Tree of Life Babak Tabarraee Carl Laamanen Design Shaun Inouye Native American Filmmakers Reclaiming Voices: Innovative 21 Artwork Voice-Overs in Chris Eyre’s Skins Soroosh Roohbakhsh Laura Beadling Faculty Advisor The Voice-Over as an Integrating Tool of Word and Image 27 Lisa Coulthard Stephen Teo Program Administrator Gerald Vanderwoude Voice-Over, Narrative Agency, and Oral Culture: 33 Graduate Secretary Ousmane Sembène’s Borom Sarret Karen Tong Alexander Fisher Editorial Board Michael Baker, Chelsea Birks, Jonathan Cannon, Robyn Citizen, Shaun Inouye, Peter Lester Public Relations Dana Keller Web Editor Oliver Kroener Cinephile would like to thank the following offices and departments Printing at the University of British Columbia for their generous support: East Van Graphics Offices of the Vice President Research & International CINEPHILE is published by the Graduate Faculty of Arts Program in Film Studies at the Depart- Department of Asian Studies ment of Theatre and Film, University of Department of Central, Eastern and North European Studies British Columbia, with the support of the Department of Classical, Near Eastern and Religious Studies Centre for Cinema Studies Department of French, Hispanic and Italian Studies centreforcinemastudies.com Department of History Department of Philosophy UBC Film Program Department of Political Science Department of Theatre and Film Department of Psychology 6354 Crescent Road School of Library, Archival & Information Studies Vancouver, BC, Canada School of Music V6T 1Z2 Editor’s Note Contributors While it is true that film has been historically considered culture. -

Reviewing Romcom: (100) Imdb Users and (500) Days of Summer

. Volume 8, Issue 2 November 2011 Reviewing Romcom: (100) IMDb Users and (500) Days of Summer Inger-Lise Kalviknes Bore Birmingham City University, UK Abstract This article contributes to academic debates around the romantic comedy genre and comedy audiences by examining IMDb user reviews of (500) Days of Summer (2009). Directed by Marc Webb for Fox Searchlight Pictures, (500) Days of Summer was promoted with the tagline ‘Boy meets girl. Boy falls in love. Girl doesn’t’. This presents the film as an unconventional romantic comedy in at least three ways: Firstly, it suggests that these two characters will not actually end up together, which challenges the idea of the romcom couple as ‘meant to be’. Secondly, it presents the possibility that audiences might not get the happy ending we usually expect from comedy. And finally, the tagline casts the boy, rather than the girl, in the role as yearning romantic, thereby challenging the traditional gender roles of heterosexual relationships. So how did audiences respond to this film? At the time of writing, it has been rated by 75,716 IMDb users, and has an average score of 8.0 out of 10. This clearly suggests a favourable reception, but the IMDb reviews also offer qualitative data that can shed further light on how the film has been evaluated. What kinds of criteria are in operation? What elements do reviewers highlight as important for their experiences of the film? How is the film seen to fail for some viewers? Drawing on previous studies of romantic comedy, the analysis will consider how these particular audience members articulated their responses to (500) Days of Summer, as well as their positions as reviewers. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Rosie Johnston Combined

ROSIE JOHNSTON MAKEUP CELEBRITIES Adam Brody Ed Helms Jim Sturgess Adam Scott Emile Hirsch Joe Manganiello Ali Hillis Emily Deschanel Joel McHale Alia Shawkat Emily Montague John F. Daley Allison Miller Emily VanCamp John Mayer Alyson Hannigan Eric Close Jon Cryer Amanda Brooks George Lopez Jonathan Goldstein Andy Samberg Grace Park Josh Holloway Angie Everhart Guy Pearce Kara DioGuardi America Ferrera Hank Azaria Kelly Preston Andrea Bowen Hayden Christensen Kerr Smith AnnaLynne McCord Ian Somerhalder Kylie Minogue Anthony LaPaglia Isla Fisher Laura Prepon Beth Riesgraf Jacinda Barrett Lisa Paulsen Billy Burke Jackie Earle Haley Lizzy Caplan Breckin Meyer Jacqueline Pinol Lorraine Bracco Brenda Strong Jake Hoffman Lucy Hale Bryan Cranston James Wolk Lucy Punch Calista Flockhart James Woods Luke Grimes Cate Blanchett James McAvoy Mark Ballas Charlie Sheen Jane Adams Matt Bomer Chris Hemsworth Jared Harris Melissa Rivers Christina Hendricks Jason Bateman Michael Vartan Courteney Cox Arquette Jason Lee Mimi Rogers Danielle Campbell Jason Ritter Minka Kelly Danielle Panabaker Jayma Mays Mireille Enos Dannii Minogue Jeffrey Dean Morgan Nick Swardson Danny Masterson Jenna Elfman Olivia Crocicchia Diablo Cody Jennifer Siebel Paul McCartney Dr. Oz Jeremy Sisto Paul Rudd 1 CELEBRITIES CONT. Poppy Montgomery Simon Baker Virginia Williams Portia De Rossi Sophie Marceau Walton Goggins Rashida Jones Steve Martin Will Arnet Ray Liotta Talulah Riley Yin Chang Rob Morrrow Tammin Sursok Zack Snyder Ron Howard Tiffany Dunn Zooey Deschanel Roxy Olin Tim -

“500 Days in Downtown L.A.” Walking Tour

“500 DAYS IN DOWNTOWN L.A.” WALKING TOUR Selected historic locations from the 2009 Fox Searchlight film “(500) Days of Summer” For much more information about the rich history of this area, including these and other landmarks, take the Los Angeles Conservancy’s walking tour, Downtown Renaissance: Spring & Main. For details, visit laconservancy.org/tours [Suggested route] Start at: SAN FERNANDO BUILDING 400 South Main Street (at Fourth Street) Original Building: John F. Blee, 1907 Addition (top two stories): R. B. Young, 1911 Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument #728 Listed in the National Register of Historic Places In the film, Old Bank DVD serves as the video & record store. • Designed in the Renaissance Revival style • Commissioned by James B. Lankershim, one of the largest landholders in California (his father Isaac helped develop the San Fernando Valley for farming) • Originally had a café, billiard room, and Turkish bath in the basement for tenants • Achieved local attention in 1910, when a series of police raids occurred on the sixth floor due to illegal gambling in the rooms • Redeveloped by Gilmore Associates; reopened in 2000 as seventy loft- style apartments—one of the early projects that sparked downtown’s current renaissance Look diagonally across Main Street (northwest corner of Fourth & Main): “500 Days in Downtown L.A.” Walking Tour Page 1 of 6 VAN NUYS HOTEL (Barclay Hotel) 103 West Fourth Street Morgan and Walls, 1896 Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument #288 In the film, the Barclay lobby serves as the hangout for -

Joseph Gordon-Levitt to Host 2013 Sundance Film Festival Awards Ceremony

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: January 4, 2013 Casey De La Rosa 310.360.1981 [email protected] JOSEPH GORDON-LEVITT TO HOST 2013 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL AWARDS CEREMONY Park City, UT — Sundance Institute announced today that actor, writer and director Joseph Gordon- Levitt will host the 2013 Sundance Film Festival feature film Awards Ceremony on January 26 in Park City, Utah and live-streamed at www.sundance.org/festival. The Festival takes place January 17-27 in Park City, Salt Lake City, Ogden and Sundance, Utah. As an actor, Gordon-Levitt has appeared in seven films at the Festival, including Mysterious Skin, Brick, and (500) Days of Summer. His directing debut, the short film, Sparks, premiered at the 2009 Festival, and his online production company hitRECord had a featured installation in New Frontier the following year as well as a live performance event at the 2012 Festival. Additionally, his feature film directorial debut, Don Jon’s Addiction, will screen in the out-of-competition Premieres section at the 2013 Festival, and Gordon-Levitt is an Artist Trustee of Sundance Institute. John Cooper, Director of the Sundance Film Festival, said, “Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s accomplished and original artistic perspectives have contributed greatly to Sundance Institute and the independent film community. As host, he is sure to add flair to our Awards Ceremony in similarly exciting ways, and we are thrilled that he will join us in recognizing outstanding achievements at this year’s Festival.” Awards for short films will be announced at a separate ceremony on January 22 at Park City’s Jupiter Bowl. -

SFX’S Horror Columnist Peers Into If You’Re New to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones Movie

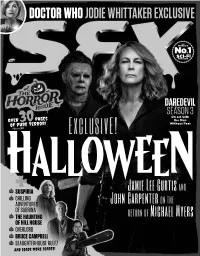

DOCTOR WHO JODIE WHITTAKER EXCLUSIVE SCI-FI 306 DAREDEVIL SEASON 3 On set with Over 30 pages the Man of pure terror! Without Fear featuring EXCLUSIVE! HALLOWEEN Jamie Lee Curtis and SUSPIRIA CHILLING John Carpenter on the ADVENTURES OF SABRINA return of Michael Myers THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE OVERLORD BRUCE CAMPBELL SLAUGHTERHOUSE RULEZ AND LOADS MORE SCARES! ISSUE 306 NOVEMBER Contents2018 34 56 61 68 HALLOWEEN CHILLING DRACUL DOCTOR WHO Jamie Lee Curtis and John ADVENTURES Bram Stoker’s great-grandson We speak to the new Time Lord Carpenter tell us about new OF SABRINA unearths the iconic vamp for Jodie Whittaker about series 11 Michael Myers sightings in Remember Melissa Joan Hart another toothsome tale. and her Heroes & Inspirations. Haddonfield. That place really playing the teenage witch on CITV needs a Neighbourhood Watch. in the ’90s? Well this version is And a can of pepper spray. nothing like that. 62 74 OVERLORD TADE THOMPSON A WW2 zombie horror from the The award-winning Rosewater 48 56 JJ Abrams stable and it’s not a author tells us all about his THE HAUNTING OF Cloverfield movie? brilliant Nigeria-set novel. HILL HOUSE Shirley Jackson’s horror classic gets a new Netflix treatment. 66 76 Who knows, it might just be better PENNY DREADFUL DAREDEVIL than the 1999 Liam Neeson/ SFX’s horror columnist peers into If you’re new to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones movie. her crystal ball to pick out the superhero shows, this third season Fingers crossed! hottest upcoming scares. is probably a bad place to start. -

500 Days of Summer

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES Presents a WATERMARK PRODUCTION JOSEPH GORDON-LEVITT ZOOEY DESCHANEL GEOFFREY AREND CHLOË GRACE MORETZ MATTHEW GRAY GUBLER CLARK GREGG RACHEL BOSTON MINKA KELLY DIRECTED BY.............................................................. MARC WEBB WRITTEN BY................................................................ SCOTT NEUSTADTER & ........................................................................................ MICHAEL H. WEBER PRODUCED BY ............................................................ JESSICA TUCHINSKY ........................................................................................ MARK WATERS ........................................................................................ MASON NOVICK ........................................................................................ STEVEN J. WOLFE DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY................................ ERIC STEELBERG PRODUCTION DESIGNER.......................................... LAURA FOX FILM EDITOR............................................................... ALAN EDWARD BELL MUSIC SUPERVISOR .................................................. ANDREA VON FOERSTER MUSIC BY..................................................................... MYCHAEL DANNA & ........................................................................................ ROB SIMONSEN COSTUME DESIGNER ................................................ HOPE HANAFIN CASTING BY ................................................................ EYDE BELASCO, CSA -

V\Illwms College. Selecting This Option Will Assign Copyright to the College

\VILLIAMS COLLEGE LIBRARIES COPYRIGHT ASSIGNl:vfENT A:'XD INSTRUCTIONS FOR A STUDENT THESIS Your unpublished thesis, submitted for a degree at Williams College and administered b:;.• the vVillimns College Libraries. will be made available for research use. You may. through thts form, provide instructions regarding copyrigl1L access, dissemination ami reproduction of your thesis. The College has the right in all cases to maintain and preserve theses both in hardcopy and electronic format. 8nd to make such copws as the Libraries require for their research and archival functions. -~- .. The faculty advisor/s to the student writing the thesis claims joint a<tthoc>hip in this \vork. ].\ve have included in this thesis copyrighted material 1<•r which I/we have not rec'''1ved permission from the copyright holden's. lf you c.o 11ot ~;t:c<:re copyright penni~sions by the time your thesis is submitted. you \vi!\ stiil be allowed to subu:it. However. if the necessary copyright periuissions are not r<:ceived. <:-posti11g of your the~is may be affected. Copyrighted material may inch!.·:le images (tables. drawings. photographs, figures. maps, graphs. etc.). sound files. video L'1aterial. data sets and large portioHs of text. I. _CQf.YRI CiHI An mnhor by hw O'>VH:> the copyright to hi.s/her work. whether or not <1 copyright symbol ancl cbte are placed on th: ptece Please choose one of the options below with re~pect to the copyright in your thesis. ___ l \w choose not to retain the copyright to the thesis, nnd hereby assign the copyright t() v\illwms College.