Copyright Vs. Napster: the File Sharing Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Napster: Winning the Download Race in Europe

Resolution 3.5 July/Aug 04 25/6/04 12:10 PM Page 50 business Napster: winning the download race in Europe A lot of ones and zeros have passed under the digital bridge on the information highway since November 2002, when this column reviewed fledgling legal music download services. Apple has proved there’s money to be made with iTunes music store, street-legal is no longer a novelty, major labels are no longer in the game ... but the Napster name remains. NIGEL JOPSON N RESOLUTION V1.5 Pressplay, co-owned by UK. There’s an all-you-can-download 7-day trial for Universal and Sony, received top marks for user UK residents who register at the Napster.co.uk site. Iexperience. Subscription service Pressplay launched While Apple has gone with individual song sales, with distribution partnerships from Microsoft’s MSN Roxio has stuck to the subscription model and service, Yahoo and Roxio. Roxio provided the CD skewed pricing accordingly. ‘We do regard burning technology. In November 2002, Roxio acquired subscription as the way forward for online music,’ the name and assets of the famed Napster service (which Leanne Sharman told me, ‘why pay £9.90 for 10 was in Chapter 11 protective bankruptcy) for US$5m songs when the same sum gives you unlimited access and 100,000 warrants in Roxio shares. Two months to over half a million tracks?’ earlier, Napster’s sale to Bertelsmann had been blocked Subscription services have come in for heavy — amid concerns the deal had not been done in good criticism from many informed commentators — mostly faith — this after Thomas Middlehoff had invested a multi-computer and iPod owning techno journalists like reputed US$60m of Bertelsmann’s money in Napster. -

Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLS\7-1\HLS101.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-MAR-16 12:46 Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms Loren Shokes* In the age of iPods, YouTube, Spotify, social media, and countless numbers of apps, anyone with a computer or smartphone readily has access to millions of hours of music. Despite the ever-increasing ease of delivering music to consumers, the recording industry has fallen victim to “the disease of free.”1 When digital music was first introduced in the late 1990s, indus- try experts and insiders postulated that it would parallel the introduction and eventual mainstream acceptance of the compact disc (CD). When CDs became publicly available in 1982,2 the music industry experienced an un- precedented boost in sales as consumers, en masse, traded in their vinyl records and cassette tapes for sleek new compact discs.3 However, the intro- duction of MP3 players and digital music files had the opposite effect and the recording industry has struggled to monetize and profit from the digital revolution.4 The birth of the file sharing website Napster5 in 1999 was the start of a sharp downhill turn for record labels and artists.6 Rather than pay * J.D. Candidate, Harvard Law School, Class of 2017. 1 See David Goldman, Music’s Lost Decade: Sales Cut in Half, CNN Money (Feb. 3, 2010), available at http://money.cnn.com/2010/02/02/news/companies/napster_ music_industry/. 2 See The Digital Era, Recording History: The History of Recording Technology, available at http://www.recording-history.org/HTML/musicbiz7.php (last visited July 28, 2015). -

The Quality of Recorded Music Since Napster: Evidence Based on The

Digitization and the Music Industry Joel Waldfogel Conference on the Economics of Information and Communication Technologies Paris, October 5-6, 2012 Copyright Protection, Technological Change, and the Quality of New Products: Evidence from Recorded Music since Napster AND And the Bands Played On: Digital Disintermediation and the Quality of New Recorded Music Intro – assuring flow of creative works • Appropriability – may beget creative works – depends on both law and technology • IP rights are monopolies granted to provide incentives for creation – Harms and benefits • Recent technological changes may have altered the balance – First, file sharing makes it harder to appropriate revenue… …and revenue has plunged RIAA Total Value of US Shipments, 1994-2009 16000 14000 12000 10000 total 8000 digital $ millions physical 6000 4000 2000 0 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Ensuing Research • Mostly a kerfuffle about whether file sharing cannibalizes sales • Oberholzer-Gee and Strumpf (2006),Rob and Waldfogel (2006), Blackburn (2004), Zentner (2006), and more • Most believe that file sharing reduces sales • …and this has led to calls for strengthening IP protection My Epiphany • Revenue reduction, interesting for producers, is not the most interesting question • Instead: will flow of new products continue? • We should worry about both consumers and producers Industry view: the sky is falling • IFPI: “Music is an investment-intensive business… Very few sectors have a comparable proportion of sales -

Illegal File Sharing

ILLEGAL FILE SHARING The sharing of copyright materials such as MUSIC or MOVIES either through P2P (peer-to-peer) file sharing or other means WITHOUT the permission of the copyright owner is ILLEGAL and can have very serious legal repercussions. Those found GUILTY of violating copyrights in this way have been fined ENORMOUS sums of money. Accordingly, the unauthorized distribution of copyrighted materials is PROHIBITED at Bellarmine University. The list of sites below is provided by Educause and some of the sites listed provide some or all content at no charge; they are funded by advertising or represent artists who want their material distributed for free, or for other reasons. Remember that just because content is free doesn't mean it's illegal. On the other hand, you may find websites offering to sell content which are not on the list below. Just because content is not free doesn't mean it's legal. Legal Alternatives for Downloading • ABC.com TV Shows • [adult swim] Video • Amazon MP3 Downloads • Amazon Instant Video • AOL Music • ARTISTdirect Network • AudioCandy • Audio Lunchbox • BearShare • Best Buy • BET Music • BET Shows • Blackberry World • Blip.fm • Blockbuster on Demand • Bravo TV • Buy.com • Cartoon Network Video • Zap2it • Catsmusic • CBS Video • CD Baby • Christian MP Free • CinemaNow • Clicker (formerly Modern Feed) • Comedy Central Video • Crackle • Criterion Online • The CW Video • Dimple Records • DirecTV Watch Online • Disney Videos • Dish Online • Download Fundraiser • DramaFever • The Electric Fetus • eMusic.com -

AT&T MOBILE MUSIC: Take Control of Your Music

AT&T MOBILE MUSIC: Take Control of Your Music AT&T Mobile Music is the only service that lets you bring subscription music services to your wireless phone, and it offers the largest collection of mobile music content available today from leading music retailers, such as Napster, Yahoo!® Music and eMusic. Designed to deliver “your music, your way,” AT&T Mobile Music puts you in touch with all things music directly from the handset. Available on select handsets, such as the Samsung a717 and a727, AT&T Mobile Music is the ultimate mobile music experience and provides one-click access to a complete suite of music-related content. Music Player Rip music from your CD collection, load it to your phone and select handsets, or play tracks that are accessible from digital music stores. You’ll need a data cable, memory card and stereo headset to fully rock your phone. Shop Music Show your style by downloading ringtones and Answer Tones™. Buy tracks from leading digital music stores, such as Napster, Yahoo! Music and eMusic on select handsets. Streaming Music When you need a change from your music, dozens of commercial-free channels stream the latest tunes in rock, hip-hop, jazz, Latin and other favorites. Add XM Radio or MobiRadio for $8.99 a month. Music Video With an AT&T 3G phone, you can watch your favorite music videos anytime, anywhere. The dancing, the amazing effects, the hot hits — all in the palm of your hand. MusicID “Who sings this?” “What’s this song called?” Know in a flash just by holding up your phone to the music. -

Beyond Napster, Beyond the United States: the Technological and International Legal Barriers to On-Line Copyright Enforcement

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 46 Issue 1 Judge Jon. O. Newman: A Symposium Celebrating his Thirty Years on the Federal Article 10 Bench January 2003 BEYOND NAPSTER, BEYOND THE UNITED STATES: THE TECHNOLOGICAL AND INTERNATIONAL LEGAL BARRIERS TO ON-LINE COPYRIGHT ENFORCEMENT Jeffrey L. Dodes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Communications Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Litigation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey L. Dodes, BEYOND NAPSTER, BEYOND THE UNITED STATES: THE TECHNOLOGICAL AND INTERNATIONAL LEGAL BARRIERS TO ON-LINE COPYRIGHT ENFORCEMENT, 46 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2002-2003). This Note is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. \\server05\productn\N\NLR\46-1-2\NLR102.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-FEB-03 13:48 BEYOND NAPSTER, BEYOND THE UNITED STATES: THE TECHNOLOGICAL AND INTERNATIONAL LEGAL BARRIERS TO ON-LINE COPYRIGHT ENFORCEMENT I. INTRODUCTION Courts in the United States and throughout the world are faced with great challenges in adjudicating legal conflicts created by the rapid development of digital technologies. The proliferation of new technologies that allow for fast, reliable and widespread transmission of digital files has recently created a swell of litigation and media cover- age throughout the world. Copyright -

Internet Radio: an Analysis of Pandora and Spotify

Internet Radio: An Analysis of Pandora and Spotify BY Corinne Loiacono ADVISOR • Jim Bishop EDITORIAL REVIEWER • Phyllis Schumacher _________________________________________________________________________________________ Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors in the Bryant University Honors Program APRIL 2014 Internet Radio Customizations: An Analysis of Pandora and Spotify Senior Capstone Project for Corinne Loiacono Table of Contents Acknowledgements: ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract: ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction: ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Review of Literature: .................................................................................................................................... 7 An Overview of Pandora: ................................................................................................................ 7 An Overview of Spotify: ............................................................................................................... 10 Other Mediums: ............................................................................................................................. 12 A Comparison: .............................................................................................................................. -

To Stream, to Spend, Or to Steal? Alexa Koch University

RUNNING HEAD: THE DIGITALIZATION OF MUSIC 1 The Digitalization of Music: To Stream, To Spend, or To Steal? Alexa Koch University of Miami RUNNING HEAD: THE DIGITALIZATION OF MUSIC 2 Abstract A music-streaming format delivers audio files or radio waves on a continuous basis, often through a subscription or verified user account. Streaming can be hosted traditionally, on a computer or Internet-enabled device, or via Bluetooth or other connectivity technology. Today, audio streaming accounts for almost one-third of the music industry; this forces record labels, organizations, and legislators, amongst others, to question the role played by music pirates in an industry so dominated by technological means of transmission. Critics suggest that there may be a link between streaming and piracy, such that the former enables the latter and that the two can coexist in a world dominated by music- streaming services. This link might exist within, and be more prevalent within, certain demographics, such as male millennials, but there is no evidence that all music streamers and paid subscribers. Keywords: music streaming, P2P file-sharing, music piracy, sound culture RUNNING HEAD: THE DIGITALIZATION OF MUSIC 3 The Digitalization of Music: To Stream, To Spend, or To Steal? Introduction Music streaming continues to grow, a force to be reckoned with, even as the rise in sales of vinyl has gone up in the last few years. Total revenue from all streaming services, which includes both passive and active streaming media, surpassed that of paid downloads by $1 million last year (Rosenblatt, 2016). According to the Recording Industry Association of America’s (RIAA) 2016 Mid-Year Report on Music Shipment and Revenue Statistics, streaming music revenues from the first half of 2016 totaled $1.6 billion, “up 57% year-over-year, and accounted for 47% of industry revenues compared with 32% [in the first half of 2015],” a figure that includes revenues from subscription services, streaming radio services, and non-subscription on-demand services. -

Title: P2P Networks for Content Sharing

Title: P2P Networks for Content Sharing Authors: Choon Hoong Ding, Sarana Nutanong, and Rajkumar Buyya Grid Computing and Distributed Systems Laboratory, Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering, The University of Melbourne, Australia (chd, sarana, raj)@cs.mu.oz.au ABSTRACT Peer-to-peer (P2P) technologies have been widely used for content sharing, popularly called “file-swapping” networks. This chapter gives a broad overview of content sharing P2P technologies. It starts with the fundamental concept of P2P computing followed by the analysis of network topologies used in peer-to-peer systems. Next, three milestone peer-to-peer technologies: Napster, Gnutella, and Fasttrack are explored in details, and they are finally concluded with the comparison table in the last section. 1. INTRODUCTION Peer-to-peer (P2P) content sharing has been an astonishingly successful P2P application on the Internet. P2P has gained tremendous public attention from Napster, the system supporting music sharing on the Web. It is a new emerging, interesting research technology and a promising product base. Intel P2P working group gave the definition of P2P as "The sharing of computer resources and services by direct exchange between systems". This thus gives P2P systems two main key characteristics: • Scalability: there is no algorithmic, or technical limitation of the size of the system, e.g. the complexity of the system should be somewhat constant regardless of number of nodes in the system. • Reliability: The malfunction on any given node will not effect the whole system (or maybe even any other nodes). File sharing network like Gnutella is a good example of scalability and reliability. -

The Napster Case: the Whole World Is Listening, 15 Transnat'l Law

Global Business & Development Law Journal Volume 15 Issue 2 Symposium: Beyond Napster -- The Future of Article 7 the Digital Commons 1-1-2002 The aN pster Case: The Whole World is Listening Grace J. Bergen General Counsel for MTS, Inc. d/b/a Tower Records Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/globe Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Grace J. Bergen, The Napster Case: The Whole World is Listening, 15 Transnat'l Law. 259 (2002). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/globe/vol15/iss2/7 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Law Reviews at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Global Business & Development Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Napster Case: The Whole World is Listening Grace J. Bergen* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: IS NAPSTER DEAD? ................................... 260 A. Napsterand Its Progeny ......................................... 260 B. The Recording Industry Dilemma ................................. 261 1I. BACKGROUND OF THE NAPSTER DECISION ............................. 261 A. The District CourtDecision ...................................... 261 1. Napster's "Safe Harbor"Arguments .......................... 262 2. Napster's FairUse Arguments ................................ 263 i. Works on NapsterAre Not "Transformative".............. 263 ii. Negative Economic Impact............................... -

It's Really Important That You Think About How We Can Move

“ It’s really important that you think about how we can move faster, how we can do things better, and not be satisfied that just because we did it in the way we used to do it, that we should Daniel Ek continue to do it so ” lv Co-Founder and CEO of Spotify Summary Daniel Ek is co-founder and CEO of the online music service Spotify. The Anglo-Swedish company launched to subscribers in 2008, and by 2011 had some 10 million registered users. It boasts former Facebook president Sean Parker as one of its board members. As with any internet business, it’s hard to put a value on Spotify, but estimates hover around the $1 billion mark, despite the fact that it’s not yet in profit. Among the factors behind Spotify’s rapid growth are timing, technical excellence, a business model that has managed to attract more than 2.5 million paying subscribers plus revenues from advertising, and a passion for continuous innovation and improvement. Spotify 104 Timeline Profile 2006 Daniel Ek and Martin Daniel Ek started to develop Spotify in 2006, together with fellow Lorentzon start to develop Spotify Swede Martin Lorentzon. Both had previous experience of setting 2008 Spotify launches for up internet businesses but Spotify was something bigger and public access more ambitious. They wanted to change the way people listened 2009 The service becomes to music, and to offer a legal and more convenient alternative to available on the App Store, and launches music piracy. on iPhone and Android Ek and Lorentzon launched Spotify in 2008. -

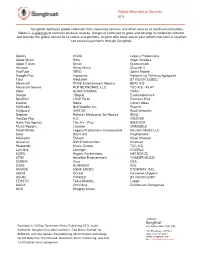

Global Mechanical Sources Songtrust

Global Mechanical Sources 2018 Songtrust optimizes global collection from streaming services and other sources of mechanical royalties. Below is a selection of common revenue sources. Songtrust continues to grow and develop its collection network and provide this global service to its clients and partners. Anyone who owes you or your writers mechanical royalties can process payments through Songtrust. Spotify KODA Legacy Productions Apple Music Rdio Virgin America Apple iTunes Smule Grooveshark Amazon Wimp Music Channel 4 YouTube VEVO Sprint Mobile Google Play Ingrooves National'nyj Tsifrovoj Agregator Tidal MediaNet BT VISION SUBSC Microsoft PFIVE Entertainment Mexico BEAT A/S Microsoft Groove PLR NETWORKS, LLC TDC A/S - PLAY XBox BUMA STEMRA FNAC Deezer 7Digital Euromediashack BeatPort LOVE FILM Premium Elite Slacker Nokia Library Ideas MixRadio Bell Mobility Inc. Playnet MySpace IMATCH Real Networks Napster Editores Mexicanos De Musica IMVU YouSee Play A.C. VIDZONE Harry Fox Agency Tdc A/s - Play BIBZOOM Music Reports Livewire ONMOBILE Mood Media Legacy Productions Incorporated Neurotic Media LLC Sony BEAT A/S PlayNetwork MixRadio EMusic Clear Channel Universal AMI Entertainment Discover Rhapsody Music Choice TDC A/S Lyricfind Limelight HOOPLA MCPS Rogers Packetvideo METROPCS STIM Headline Entertainment YONDER MUSIC CMRRA Zuus OSA SGAE BLINKBOX AOL AMCOS MUVE MUSIC STEINWAY, INC. SACM Cricket Ediciones Clippers ACUM YANDEX BT VISION LIMIT TEOSTO Tellus Mobility Labels SUISA Omnifone Distribution Companies NCB Stingray Music CONTACT Songtrust Founded in 2010 by Downtown Music Publishing CEO, Justin HQ: Soho, New York City Kalifowitz, Songtrust has been named a "Top Music Startup" by 485 Broadway, 3rd Floor Billboard, and now powers the publishing administration technology New York, NY 10013 www.songtrust.com for CD Baby Pro, The Orchard, Downtown Music Publishing, and over E.