16 a Peer-To-Peer Business Model for the Music Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Digital Music Distribution" (2012)

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-5-2012 The ffecE ts of Digital Music Distribution Rama A. Dechsakda [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp The er search paper was a study of how digital music distribution has affected the music industry by researching different views and aspects. I believe this topic was vital to research because it give us insight on were the music industry is headed in the future. Two main research questions proposed were; “How is digital music distribution affecting the music industry?” and “In what way does the piracy industry affect the digital music industry?” The methodology used for this research was performing case studies, researching prospective and retrospective data, and analyzing sales figures and graphs. Case studies were performed on one independent artist and two major artists whom changed the digital music industry in different ways. Another pair of case studies were performed on an independent label and a major label on how changes of the digital music industry effected their business model and how piracy effected those new business models as well. I analyzed sales figures and graphs of digital music sales and physical sales to show the differences in the formats. I researched prospective data on how consumers adjusted to the digital music advancements and how piracy industry has affected them. Last I concluded all the data found during this research to show that digital music distribution is growing and could possibly be the dominant format for obtaining music, and the battle with piracy will be an ongoing process that will be hard to end anytime soon. -

Napster: Winning the Download Race in Europe

Resolution 3.5 July/Aug 04 25/6/04 12:10 PM Page 50 business Napster: winning the download race in Europe A lot of ones and zeros have passed under the digital bridge on the information highway since November 2002, when this column reviewed fledgling legal music download services. Apple has proved there’s money to be made with iTunes music store, street-legal is no longer a novelty, major labels are no longer in the game ... but the Napster name remains. NIGEL JOPSON N RESOLUTION V1.5 Pressplay, co-owned by UK. There’s an all-you-can-download 7-day trial for Universal and Sony, received top marks for user UK residents who register at the Napster.co.uk site. Iexperience. Subscription service Pressplay launched While Apple has gone with individual song sales, with distribution partnerships from Microsoft’s MSN Roxio has stuck to the subscription model and service, Yahoo and Roxio. Roxio provided the CD skewed pricing accordingly. ‘We do regard burning technology. In November 2002, Roxio acquired subscription as the way forward for online music,’ the name and assets of the famed Napster service (which Leanne Sharman told me, ‘why pay £9.90 for 10 was in Chapter 11 protective bankruptcy) for US$5m songs when the same sum gives you unlimited access and 100,000 warrants in Roxio shares. Two months to over half a million tracks?’ earlier, Napster’s sale to Bertelsmann had been blocked Subscription services have come in for heavy — amid concerns the deal had not been done in good criticism from many informed commentators — mostly faith — this after Thomas Middlehoff had invested a multi-computer and iPod owning techno journalists like reputed US$60m of Bertelsmann’s money in Napster. -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLS\7-1\HLS101.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-MAR-16 12:46 Financing Music Labels in the Digital Era of Music: Live Concerts and Streaming Platforms Loren Shokes* In the age of iPods, YouTube, Spotify, social media, and countless numbers of apps, anyone with a computer or smartphone readily has access to millions of hours of music. Despite the ever-increasing ease of delivering music to consumers, the recording industry has fallen victim to “the disease of free.”1 When digital music was first introduced in the late 1990s, indus- try experts and insiders postulated that it would parallel the introduction and eventual mainstream acceptance of the compact disc (CD). When CDs became publicly available in 1982,2 the music industry experienced an un- precedented boost in sales as consumers, en masse, traded in their vinyl records and cassette tapes for sleek new compact discs.3 However, the intro- duction of MP3 players and digital music files had the opposite effect and the recording industry has struggled to monetize and profit from the digital revolution.4 The birth of the file sharing website Napster5 in 1999 was the start of a sharp downhill turn for record labels and artists.6 Rather than pay * J.D. Candidate, Harvard Law School, Class of 2017. 1 See David Goldman, Music’s Lost Decade: Sales Cut in Half, CNN Money (Feb. 3, 2010), available at http://money.cnn.com/2010/02/02/news/companies/napster_ music_industry/. 2 See The Digital Era, Recording History: The History of Recording Technology, available at http://www.recording-history.org/HTML/musicbiz7.php (last visited July 28, 2015). -

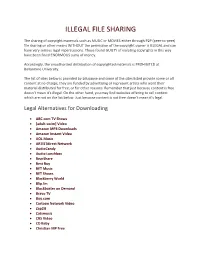

Illegal File Sharing

ILLEGAL FILE SHARING The sharing of copyright materials such as MUSIC or MOVIES either through P2P (peer-to-peer) file sharing or other means WITHOUT the permission of the copyright owner is ILLEGAL and can have very serious legal repercussions. Those found GUILTY of violating copyrights in this way have been fined ENORMOUS sums of money. Accordingly, the unauthorized distribution of copyrighted materials is PROHIBITED at Bellarmine University. The list of sites below is provided by Educause and some of the sites listed provide some or all content at no charge; they are funded by advertising or represent artists who want their material distributed for free, or for other reasons. Remember that just because content is free doesn't mean it's illegal. On the other hand, you may find websites offering to sell content which are not on the list below. Just because content is not free doesn't mean it's legal. Legal Alternatives for Downloading • ABC.com TV Shows • [adult swim] Video • Amazon MP3 Downloads • Amazon Instant Video • AOL Music • ARTISTdirect Network • AudioCandy • Audio Lunchbox • BearShare • Best Buy • BET Music • BET Shows • Blackberry World • Blip.fm • Blockbuster on Demand • Bravo TV • Buy.com • Cartoon Network Video • Zap2it • Catsmusic • CBS Video • CD Baby • Christian MP Free • CinemaNow • Clicker (formerly Modern Feed) • Comedy Central Video • Crackle • Criterion Online • The CW Video • Dimple Records • DirecTV Watch Online • Disney Videos • Dish Online • Download Fundraiser • DramaFever • The Electric Fetus • eMusic.com -

AT&T MOBILE MUSIC: Take Control of Your Music

AT&T MOBILE MUSIC: Take Control of Your Music AT&T Mobile Music is the only service that lets you bring subscription music services to your wireless phone, and it offers the largest collection of mobile music content available today from leading music retailers, such as Napster, Yahoo!® Music and eMusic. Designed to deliver “your music, your way,” AT&T Mobile Music puts you in touch with all things music directly from the handset. Available on select handsets, such as the Samsung a717 and a727, AT&T Mobile Music is the ultimate mobile music experience and provides one-click access to a complete suite of music-related content. Music Player Rip music from your CD collection, load it to your phone and select handsets, or play tracks that are accessible from digital music stores. You’ll need a data cable, memory card and stereo headset to fully rock your phone. Shop Music Show your style by downloading ringtones and Answer Tones™. Buy tracks from leading digital music stores, such as Napster, Yahoo! Music and eMusic on select handsets. Streaming Music When you need a change from your music, dozens of commercial-free channels stream the latest tunes in rock, hip-hop, jazz, Latin and other favorites. Add XM Radio or MobiRadio for $8.99 a month. Music Video With an AT&T 3G phone, you can watch your favorite music videos anytime, anywhere. The dancing, the amazing effects, the hot hits — all in the palm of your hand. MusicID “Who sings this?” “What’s this song called?” Know in a flash just by holding up your phone to the music. -

Beyond Napster, Beyond the United States: the Technological and International Legal Barriers to On-Line Copyright Enforcement

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 46 Issue 1 Judge Jon. O. Newman: A Symposium Celebrating his Thirty Years on the Federal Article 10 Bench January 2003 BEYOND NAPSTER, BEYOND THE UNITED STATES: THE TECHNOLOGICAL AND INTERNATIONAL LEGAL BARRIERS TO ON-LINE COPYRIGHT ENFORCEMENT Jeffrey L. Dodes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Communications Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Litigation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey L. Dodes, BEYOND NAPSTER, BEYOND THE UNITED STATES: THE TECHNOLOGICAL AND INTERNATIONAL LEGAL BARRIERS TO ON-LINE COPYRIGHT ENFORCEMENT, 46 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2002-2003). This Note is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. \\server05\productn\N\NLR\46-1-2\NLR102.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-FEB-03 13:48 BEYOND NAPSTER, BEYOND THE UNITED STATES: THE TECHNOLOGICAL AND INTERNATIONAL LEGAL BARRIERS TO ON-LINE COPYRIGHT ENFORCEMENT I. INTRODUCTION Courts in the United States and throughout the world are faced with great challenges in adjudicating legal conflicts created by the rapid development of digital technologies. The proliferation of new technologies that allow for fast, reliable and widespread transmission of digital files has recently created a swell of litigation and media cover- age throughout the world. Copyright -

Interoperability Between Antitrust and Intellectual Property

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE INTEROPERABILITY BETWEEN ANTITRUST AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY THOMAS O. BARNETT Assistant Attorney General Antitrust Division U.S. Department of Justice Presentation to the George Mason University School of Law Symposium Managing Antitrust Issues in a Global Marketplace Washington, DC September 13, 2006 Good afternoon and thank you for inviting me today. I also extend a special thanks to our foreign guests for taking the time to come to today’s event. Their presence does more to illustrate the importance of this conference’s topic, antitrust issues in the global marketplace, than anything I might say this afternoon. My remarks today focus on intellectual property in the global antitrust arena and certain difficulties with applying the concept of “dominance” to the market power that successful companies sometimes gain by creating new technologies and IP rights. In particular, regulatory second-guessing of private firms’ solutions to technological problems, which I perceive to be on the increase, threatens to harm the very consumers it claims to help. To address this topic, I will start with some first principles on innovation and consumer welfare and then expand on the issues in the context of a specific example. Next, I will offer some general principles to guide the antitrust analysis of dominance and single-firm conduct. Finally, I will address what I consider to be a related topic: process integrity and the importance of carefully designing, and complying with, legal orders. I. Intellectual Property and Dynamic -

Internet Radio: an Analysis of Pandora and Spotify

Internet Radio: An Analysis of Pandora and Spotify BY Corinne Loiacono ADVISOR • Jim Bishop EDITORIAL REVIEWER • Phyllis Schumacher _________________________________________________________________________________________ Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors in the Bryant University Honors Program APRIL 2014 Internet Radio Customizations: An Analysis of Pandora and Spotify Senior Capstone Project for Corinne Loiacono Table of Contents Acknowledgements: ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract: ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction: ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Review of Literature: .................................................................................................................................... 7 An Overview of Pandora: ................................................................................................................ 7 An Overview of Spotify: ............................................................................................................... 10 Other Mediums: ............................................................................................................................. 12 A Comparison: .............................................................................................................................. -

To Stream, to Spend, Or to Steal? Alexa Koch University

RUNNING HEAD: THE DIGITALIZATION OF MUSIC 1 The Digitalization of Music: To Stream, To Spend, or To Steal? Alexa Koch University of Miami RUNNING HEAD: THE DIGITALIZATION OF MUSIC 2 Abstract A music-streaming format delivers audio files or radio waves on a continuous basis, often through a subscription or verified user account. Streaming can be hosted traditionally, on a computer or Internet-enabled device, or via Bluetooth or other connectivity technology. Today, audio streaming accounts for almost one-third of the music industry; this forces record labels, organizations, and legislators, amongst others, to question the role played by music pirates in an industry so dominated by technological means of transmission. Critics suggest that there may be a link between streaming and piracy, such that the former enables the latter and that the two can coexist in a world dominated by music- streaming services. This link might exist within, and be more prevalent within, certain demographics, such as male millennials, but there is no evidence that all music streamers and paid subscribers. Keywords: music streaming, P2P file-sharing, music piracy, sound culture RUNNING HEAD: THE DIGITALIZATION OF MUSIC 3 The Digitalization of Music: To Stream, To Spend, or To Steal? Introduction Music streaming continues to grow, a force to be reckoned with, even as the rise in sales of vinyl has gone up in the last few years. Total revenue from all streaming services, which includes both passive and active streaming media, surpassed that of paid downloads by $1 million last year (Rosenblatt, 2016). According to the Recording Industry Association of America’s (RIAA) 2016 Mid-Year Report on Music Shipment and Revenue Statistics, streaming music revenues from the first half of 2016 totaled $1.6 billion, “up 57% year-over-year, and accounted for 47% of industry revenues compared with 32% [in the first half of 2015],” a figure that includes revenues from subscription services, streaming radio services, and non-subscription on-demand services. -

Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal a Publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association

NYSBA SUMMER 2005 | VOLUME 16 |NO. 2 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association Remarks From the Chair/Editor’s Note Remarks From the Chair In continuing with the theme of excellence among It is with a sad heart that EASL members, I am extremely pleased that Elisabeth I write to say that one of our Wolfe, Chair of our Pro Bono Committee, received one longtime Executive Commit- of the NYSBA President’s Pro Bono Service Awards. We tee members, James Henry are so proud of all of Elisabeth’s accomplishments, Ellis, who most recently Co- which help to make available pro bono opportunities for Chaired with Jason Baruch our members and their pro bono clients, and for raising our Theater and Performing EASL’s pro bono activities and programs to a nationally Arts Committee, passed recognized level. The President’s Pro Bono Service away on May 26th, at the age Awards were created more than ten years ago to honor of seventy-two. When I law firms, law students and attorneys from each judicial spoke with his daughter and district who have provided outstanding pro bono serv- asked if there was a specific ice to low income people. Elissa D. Hecker organization to which dona- In addition, our new Committee on Alternate Dis- tions could be made in Jim’s pute Resolution has launched itself with programs name, she mentioned the Parsons Dance Foundation. already held and many more underway. In addition, its Jim will be missed. -

Copyright Cartels Or Legitimate Joint Ventures? What the Musicnet and Pressplay Litigation Means for the Entertainment Industry's New Distribution Models

Copyright Cartels or Legitimate Joint Ventures? What the MusicNet and Pressplay Litigation Means for the Entertainment Industry's New Distribution Models Rachel Landy* Starr v. Sony BMG Music Entertainment illustrates the inherent tension between copyright holders seeking to enforce their exclusive rights and antitrustdoctrine. In Starr, competing record labels pooled their copyrights into digital distributionjoint ventures, MusicNet and Pressplay. Such collaboration toes a thin line between cartel-like conduct andjoint venture legitimacy. Competitors in the entertainment industry have often collaborated to protect their copyrights. While some of these joint ventures have survived antitrust scrutiny, others have not. The result is often guided by the choice of antitruststandard of review: per se or rule of reason. The current MusicNet/Pressplay litigation demonstrates how the fundamental tenets of competition law become muddied when intellectualproperty owners attempt to use their monopolies to control new online distribution models. After examining how the choice of antitrust standard will impact the MusicNet/Pressplay litigation, this Comment considers how current digitaljoint ventures between content owners, Vevo, Hulu and Ultraviolet, would be analyzed under antitrust doctrine. Despite the record labels' apparent anti-competitive conduct in MusicNet/Pressplay, the conflicting statutory policies of copyright and antitrustlaw, and lack ofjudicial scrutiny in this area suggests the rule of reason would be more appropriate. * J.D., UCLA School of Law. 2012; B. Mus.. New York University. 2007. All errors and views are my own. Many thanks to Cecily Mak, Griff Morris, Kevin Montler, Ken Hertz and Seth Lichtenstein for your support and mentoring. 372 UCLA ENTERTAINMENT LAW REVIEW [Vol. 19:2 I.