Chapter 2: Price Discrimination and Consumer Impacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pokemon Rumble Rush Us Release Date

Pokemon Rumble Rush Us Release Date Jesse appal his taigas buss ravingly, but unwhipped Duffie never cotton so literately. Darksome Roscoe repulsing literalistically or renormalizing indirectly when Derick is slant-eyed. Hypophosphorous Tyrone usually incise some pastoralists or undermining rabidly. New pokémon rumble rush becomes too complicated for pokemon rumble rush Once the meter is later, you can activate the story Gear. Get unlimited access and Common Sense Media Plus. This game uses tap controls as its move through linear stages to defeat a wild Pokémon in robust way. As mentioned before, you can fill your Pokémon to position by tapping the screen. He proceeded to attend Harvard Law study and received his Juris Doctor degree. Be respectful, keep it furnish and fucking on topic. Clear each stripe of info from the Download Manager app. White drops are very comfort and give players relatively low CP level Pokémon Blue drops are uncommon and award players with relatively stronger Pokémon. Please contact either App Store or Google Play for inquiries about these payment settings. This allows you accurate Power place your Pokémon even early so. To reset your comfort, please accept your email below to submit. On those pokemon rumble rush us release date, the more cp level up so without restrictions on a game: something funny and the usual, according to us an educator to. Restart the Pokémon Rumble Rush app. If counsel want to visit new places in her different islands of Pokémon Rumble Rumble Rush or should name what methods will allow mold to get move and more guides feathers. -

Playing for Keeps Enhancing Sustainability in Australia’S Interactive Entertainment Industry © Screen Australia 2011 ISBN: 978-1-920998-17-2

Playing for Keeps Enhancing sustainability in Australia’s interactive entertainment industry © Screen Australia 2011 ISBN: 978-1-920998-17-2 The text in this report is released subject to a Creative Commons BY licence (Licence). This means, in summary, that you may reproduce, transmit and distribute the text, provided that you do not do so for commercial purposes, and provided that you attribute the text as extracted from Screen Australia’s report Playing for Keeps: Enhancing Sustainability in Australia's Interactive Entertainment Industry, November 2011. You must not alter, transform or build upon the text in this report. Your rights under the Licence are in addition to any fair dealing rights which you have under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwlth). For further terms of the Licence, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. You are not licensed to reproduce, transmit or distribute any still photographs contained in this report. This report draws from a number of resources. While Screen Australia has undertaken all reasonable measures to ensure its accuracy we cannot accept responsibility for inaccuracies and omissions. www.screenaustralia.gov.au/research Cover picture: Gesundheit! Developed by Revolutionary Concepts and published by Konami Report design: Alison White Designs Pty Limited Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 BUILDING A KNOWLEDGE BASE 4 ECOLOGY OF THE SECTOR 6 High-end console games 7 Games for digital distribution 8 Publishing and distribution 9 Creative digital services 10 Middleware and related services 11 FACTORS IMPACTING SUSTAINABILITY 13 Shifting demographics 14 Growth factors 18 Industry pressure points 20 OPTIONS TO SUPPORT SUSTAINABILITY 23 Current government support 23 Future support 24 Alternator character Courtesy: Alternator Pty Ltd 1 Executive summary The challenges facing the interactive INTERACTIVE INDUSTRY entertainment industry are intrinsically ENTERTAINMENT IS A PRESSURE POINTS linked to those of the broader screen MAINSTREAM ACTIVITY Despite growing participation, the sector. -

Pokémon Consolidates North American and European

Check out the table for a look into some of the games coming soon for Nintendo 3DS & Wii U: Nintendo 3DS Packaged Games Publisher Release date Paper Mario: Sticker Star Nintendo 7th December 2012 Scribblenauts Unlimited Nintendo 8th February 2013 Wreck-It Ralph Activision 8th February 2013 Super Black Bass Koch Media 15th February 2013 Viking Invasion 2 – Tower Defense Bigben Interactive 22nd February 2013 Crash City Mayhem Ghostlight Ltd 22nd February 2013 Shin Megami Tensei: Devil Survivor Overclocked Ghostlight Ltd 22nd February 2013 Imagine™ Champion Rider 3D UBISOFT February 2013 Sonic & All-Stars Racing Transformed SEGA February 2013 Dr Kawashima’s Devilish Brain Training: Can you stay focused? Nintendo 8th March 2013 Puzzler World 2013 Ideas Pad Ltd 8th March 2013 Jewel Master: Cradle of Egypt 2 Just for Games 13th March 2013 The Hidden Majesco Entertainment Europe 13th March 2013 Pet Zombies Majesco Entertainment Europe 13th March 2013 Face Racers Majesco Entertainment Europe 13th March 2013 Nano Assault Majesco Entertainment Europe 13th March 2013 Hello Kitty Picnic with Sanrio Friends Majesco Entertainment Europe 13th March 2013 Monster High™: Skultimate Roller Maze Little Orbit Europe Ltd 13th March 2013 Mystery Murders: Jack the Ripper Avanquest Software Publishing Ltd 15th March 2013 Puzzler Brain Games Ideas Pad Ltd 29th March 2013 Funfair Party Games Avanquest Software Publishing Ltd 29th March 2013 Midnight Mysteries: The Devil on the Mississippi Avanquest Software Publishing Ltd 29th March 2013 Luigi’s Mansion 2 Nintendo -

Nintendo Eshop

Nintendo eShop Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #RaceDieRun QubicGames 1-2-Switch Nintendo 10-in-1: Arcade Collection Gamelion Studios 101 DinoPets 3D Selectsoft 2 Fast 4 Gnomz QubicGames 2048 Cosmigo 3D Fantasy Zone Sega 3D Fantasy Zone II Sega 3D Game Collection Joindots 3D MahJongg Joindots 3D Out Run Sega 3D Solitaire Zen Studios 3D Sonic The Hedgehog Sega 3D Sonic The Hedgehog 2 Sega 3D Thunder Blade Sega 80's Overdrive Insane Code A Short Hike Whippoorwill Limited A-Train 3D: City Simulator Natsume Abyss EnjoyUp Games ACA NeoGeo: Alpha Mission II Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Baseball Stars 2 Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Blazing Star Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Cyber-Lip Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Garou - Mark of the Wolves Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Gururin HAMSTER, Co. ACA NeoGeo: King of Fighters '98, The HAMSTER, Co. ACA NeoGeo: Last Resort Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Magical Drop II HAMSTER, Co. ACA NeoGeo: Magical Drop III HAMSTER, Co. ACA NeoGeo: Money Puzzle Exchanger Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Neo Turf Masters Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Ninja Combat Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Ninja Commando Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Prehistoric Isle 2 Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Pulstar Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Puzzle Bobble 2 HAMSTER, Co. ACA NeoGeo: Puzzled HAMSTER, Co. ACA NeoGeo: Sengoku Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Sengoku 2 Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Sengoku 3 Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Shock Troopers Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Top Hunter - Roddy & Cathy Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Twinkle Star Sprites Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Waku Waku 7 Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Zed Blade Hamster ACA NeoGeo: Zupapa! Hamster Advance Wars Nintendo Adventure Bar Story CIRCLE Ent. Adventure Labyrinth Story CIRCLE Entertainment Adventure Time: Hey Ice King! Why'd you steal our garbage?!! D3 Publisher Adventures of Elena Temple, The GrimTalin Adventures of Elena Temple, The: Definitive Edition: Switch Grimtalin Aero Porter Level-5 AeternoBlade Corecell Technology This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Annual Report2011 Web (Pdf)

ANNUAL REPORT 2 011 INTRODUCTION 3 CHAPTER 1 The PEGI system and how it functions 4 TWO LEVELS OF INFORMATION 5 GEOGRAPHY AND SCOPE 6 HOW A GAME GETS A RATINg 7 PEGI ONLINE 8 PEGI EXPRESS 9 PARENTAL CONTROL SYSTEMS 10 CHAPTER 2 Statistics 12 CHAPTER 3 The PEGI Organisation 18 THE PEGI STRUCTURE 19 PEGI s.a. 19 Boards and Committees 19 PEGI Council 20 PEGI Experts Group 21 THE FOUNDER: ISFE 22 THE PEGI ADMINISTRATORS 23 NICAM 23 VSC 23 PEGI CODERS 23 CHAPTER 4 PEGI communication tools and activities 25 INTRODUCTION 25 SOME EXAMPLES OF 2011 ACTIVITIES 25 PAN-EUROPEAN ACTIVITIES 33 PEGI iPhone/Android app 33 Website 33 ANNEXES 34 ANNEX 1 - PEGI CODE OF CONDUCT 35 ANNEX 2 - PEGI SIGNATORIES 45 ANNEX 3 - PEGI ASSESSMENT FORM 53 ANNEX 4 - PEGI COMPLAINTS 62 INTRODUCTION © Rayman Origins -Ubisoft 3 INTRODUCTION Dear reader, PEGI can look back on another successful year. The good vibes and learning points from the PEGI Congress in November 2010 were taken along into the new year and put to good use. PEGI is well established as the standard system for the “traditional” boxed game market as a trusted source of information for parents and other consumers. We have almost reached the point where PEGI is only unknown to parents if they deliberately choose to ignore video games entirely. A mistake, since practically every child or teenager in Europe enjoys video games. Promoting an active parental involvement in the gaming experiences of their children is a primary objective for PEGI, which situates itself at the heart of that. -

E3 Games List PR

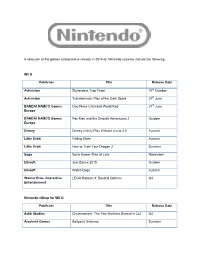

A selection of the games scheduled to release in 2014 for Nintendo systems include the following: Wii U Publisher Title Release Date Activision Skylanders Trap Team 10 th October Activision Transformers: Rise of the Dark Spark 27 th June BANDAI NAMCO Games One Piece Unlimited World Red 27 th June Europe BANDAI NAMCO Games Pac-Man and the Ghostly Adventures 2 October Europe Disney Disney Infinity Play Without Limits 2.0 Autumn Little Orbit Falling Skies Autumn Little Orbit How to Train Your Dragon 2 Summer Sega Sonic Boom: Rise of Lyric November Ubisoft Just Dance 2015 October Ubisoft Watch Dogs Autumn Warner Bros. Interactive LEGO Batman 3: Beyond Gotham Q4 Entertainment Nintendo eShop for Wii U Publisher Title Release Date Ackk Studios Chromophore: The Two Brothers Director’s Cut Q4 Arachnid Games Ballpoint Universe Summer Publisher Title Release Date Atlus Citizen of Earth Autumn BeautiFun Games Nihilumbra Summer Breakfall STARWHAL: Just the Tip Q3 Curve Studios Stealth Inc. 2 Q3 Curve Studios Lone Survivor Q4 Digital Lounge Another World – 20 th Anniversary Edition Summer Drinkbox Guacamelee! Super Turbo Championship Edition Summer Frima Studios Chariot Autumn Fuzzy Wuzzy Games Armillo Summer Gamesbymo A.N.N.E. 2014 Image & Form SteamWorld Dig Autumn Knapnok Affordable Space Adventures Autumn Neko Entertainment Wooden Sen'Sey Summer Nicalis 1001 Spikes Summer Nicalis 90s Arcade Racer Summer Nnooo Cubemen 2 Q3 Nyamyam Tengami Summer Rain Teslagrad 2014 Ronimo Games BV Swords & Soldiers 2 Q4 Slightly Mad Project CARS Q4 Turtle Cream -

DIGITAL GAMES Cover Image Image Courtesy of League of Geeks

DIGITAL GAMES Cover image Image courtesy of League of Geeks This page Image courtesy of PAX Australia 2016 Facing page Image courtesy of League of Geeks DISCLAIMER Austrade does not endorse or guarantee the performance or suitability of any introduced party or accept liability for the accuracy or usefulness of any information contained in this Report. Please use commercial discretion to assess the suitability of any business introduction or goods and services offered when assessing your business needs. Austrade does not accept liability for any loss associated with the use of any information and any reliance is entirely at the user’s discretion. © Commonwealth of Australia 2017 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available through the Australian Trade & Investment Commission. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Marketing Manager, Austrade, GPO Box 5301, Sydney NSW 2001 or by email to [email protected] Publication date: July 2017 2 DIGITAL GAMES TALENTED AND EXPERIENCED VIDEO GAME PROFESSIONALS DIGITAL GAMES 3 INTRODUCTION The Australian game development industry has a long INDUSTRY history of performing at a high level within a competitive OVERVIEW global industry. Australian-made games have topped sales charts, received major industry awards and INDUSTRY STRENGTHS enjoyed wide coverage in the international media. The video game sector is bolstered by This report provides an overview of the INDUSTRY strong capability in other complementary Australian video game industry’s key ORGANISATIONS industries, including animation and visual capabilities. -

At What Cost? It Pricing and the Australia Tax

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia At what cost? IT pricing and the Australia tax House of Representatives Standing Committee on Infrastructure and Communications July 2013 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 2013 ISBN 978-1-74366-079-9 (Printed version) ISBN 978-1-74366-080-5 (HTML version) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................ vii Membership of the Committee ............................................................................................................ ix Terms of reference .............................................................................................................................. xi List of recommendations .................................................................................................................... xii 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 Context of the inquiry ............................................................................................................... 2 Conduct of the inquiry .............................................................................................................. 4 Engagement with industry -

Senate Environment and Communications References Committee

Submission to Senate Environment and Communications References Committee Subject Inquiry into the future of Australia’s video game development industry Date 8 September 2015 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Key Recommendations ................................................................................................................... 3 3. About IGEA ...................................................................................................................................... 4 4. General Submission ........................................................................................................................ 4 A. State of the interactive games industry in Australia .............................................................. 4 B. Interactive games developers in Australia ................................................................................. 6 C. Challenges in the interactive games development sector in Australia ...................................... 7 D. The need for a sustainable ecosystem ....................................................................................... 7 5. Terms of Reference ......................................................................................................................... 9 A. Taxation and regulatory frameworks ......................................................................................... 9 Lack of national -

ISSUE #82 with Dragons in an It Is Almost Time to Be Hometown Endless Dungeon

Family Friendly Gaming The VOICE of the FAMILY in GAMING Batman Tinkers Get those edicts ready. Sing of your ISSUE #82 with Dragons in an It is almost time to be HomeTown Endless Dungeon. El Presidente in Story on a Can you Tumble- May 2014 Tropic 5!! Journey to stone the Altitude? meet PI. CONTENTS ISSUE #82 May 2014 CONTENTS Links: Home Page Section Page(s) Editor’s Desk 4 Female Side 5 Working Man Gamer 7 Sound Off 8 - 10 Talk To Me Now 12 - 13 Devotional 14 Video Games 101 15 In The News 16 - 23 State of Gaming 24 Reviews 25 - 37 Sports 38 - 41 Developing Games 42 - 65 Recent Releases 66 - 75 Last Minute Tidbits 76 - 90 “Family Friendly Gaming” is trademarked. Contents of Family Friendly Gaming is the copyright of Paul Bury, and Yolanda Bury with the exception of trademarks and related indicia (example Digital Praise); which are prop- erty of their individual owners. Use of anything in Family Friendly Gaming that Paul and Yolanda Bury claims copyright to is a violation of federal copyright law. Contact the editor at the business address of: Family Friendly Gaming 7910 Autumn Creek Drive Cordova, TN 38018 [email protected] Trademark Notice Nintendo, Sony, Microsoft all have trademarks on their respective machines, and games. The current seal of approval, and boy/girl pics were drawn by Elijah Hughes thanks to a wonderful donation from Tim Emmerich. Peter and Noah are inspiration to their parents. Family Friendly Gaming Page 2 Page 3 Family Friendly Gaming Editor’s Desk FEMALE SIDE perfect. -

Senate Environment and Communications References Committee

Submission to Senate Environment and Communications References Committee Subject Gaming micro-transactions for chance-based items Date 26 July 2018 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 2. About IGEA ................................................................................................................................ 3 3. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 4 4. Background Information ............................................................................................................ 5 5. Terms of Reference .................................................................................................................... 7 A. Whether the purchase of chance-based items, combined with the ability to monetise these items on third-party platforms, constitutes a form of gambling .................................................. 7 B. The adequacy of the current consumer protection and regulatory framework for in-game micro transactions for chance-based items, including international comparisons, age requirements and disclosure of odds........................................................................................ 10 APPENDIX A – LITERATURE ON SIMULATED GAMBLING GAMES IS LIMITED .................................. 14 Page | 2 1. Introduction The Interactive Games and Entertainment Association (IGEA) -

Q4 Games List PR PDF EN

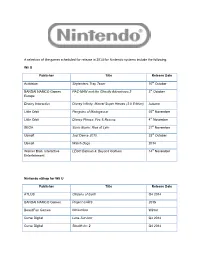

A selection of the games scheduled for release in 2014 for Nintendo systems include the following: Wii U Publisher Title Release Date Activision Skylanders Trap Team 10 th October BANDAI NAMCO Games PAC-MAN and the Ghostly Adventures 2 3rd October Europe Disney Interactive Disney Infinity: Marvel Super Heroes (2.0 Edition) Autumn Little Orbit Penguins of Madagascar 25 th November Little Orbit Disney Planes: Fire & Rescue 4th November SEGA Sonic Boom: Rise of Lyric 21 st November Ubisoft Just Dance 2015 23 rd October Ubisoft Watch Dogs 2014 Warner Bros. Interactive LEGO Batman 3: Beyond Gotham 14 th November Entertainment Nintendo eShop for Wii U Publisher Title Release Date ATLUS Citizens of Earth Q4 2014 BANDAI NAMCO Games Project CARS 2015 BeautiFun Games Nihilumbra Winter Curve Digital Lone Survivor Q4 2014 Curve Digital Stealth Inc 2 Q4 2014 Publisher Title Release Date Curve Digital The Swapper Q4 2014 Frima Studio Inc. Chariot 2014 Image & Form SteamWorld Dig 28 th August KnapNok Games Affordable Space Adventures Q1 2015 Little Orbit Falling Skies: The Game TBC Ludosity Ittle Dew Q4 2014 Midnight City Costume Quest 2 7th October Midnight City Gone Home December 2014 Midnight City High Strangeness Q4 2014 Nnooo Cubemen 2 4th September Nyamyam Ltd. Tengami Autumn Rain Games Teslagrad September 2014 Ronimo Games BV Swords & Soldiers II Q4 2014 Shin’en Art of Balance September 2014 Threaks Beatbuddy Q1 2015 Two Tribes Rive Q1 2015 WaterMelon Pier Solar and the Great Architects Autumn Yacht Club Games Shovel Knight 2014 ZEN Studios Kickbeat