Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snowschool Offered to Local Students Environment

6 TUESDAY, JANUARY 28, 2020 The Inyo Register SnowSchool offered to local students environment. The second with water. The food color- journey is unique. This Bishop, session allows students to ing and glitter represent game shows students how Mammoth review the first lesson and different, pollutants that water moves through the learn how to calculate snow might enter the watershed, earth, oceans, and atmo- Lakes fifth- water equivalent. The final and students can observe sphere, and gives them a grade students session takes students how the pollutants move better understanding of from the classroom to the and collect in different the water cycle. participate in mountains for a SnowSchool bodies of water. For the final in-class field day. Once firmly in For the second in-class activity, students learn SnowSchool snowshoes, the students activity, students focus on about winter ecology and learn about snow science the water cycle by taking how animals adapt for the By John Kelly hands-on and get a chance on the role of a water mol- winter. Using Play-Doh, Education Manager, ESIA to play in the snow. ecule and experiencing its they create fictional ani- During the in-class ses- journey firsthand. Students mals that have their own For the last five years, sion, students participate break up into different sta- winter adaptations. Some the Eastern Sierra in three activities relating tions. Each station repre- creations in past Interpretive Association to watersheds, the water sents a destination a water SnowSchools had skis for (ESIA) and Friends of the cycle, and winter ecology. molecule might end up, feet to move more easily Inyo have provided instruc- In the first activity, stu- such as a lake, river, cloud, on the snow and shovels tors who deliver the Winter dents create their own glacier, ocean, in the for hands for better bur- Wildlands Alliance’s watershed, using tables groundwater, on the soil rowing ability. -

PAT ROBERTSON TELEVANGELIST SUMMARIES March 1987

TELEVANGELIST SUMMARIES March 1987 PAT ROBERTSON Bakker scandal ••.•..•••.•• • •• 46-48 Mobile, AL textbook case. • ••• 30-37 700 CLUB BENNET, WILLIAM School-based health clinics .• ••• 37 Gay rights .••.• .37 Welfare reform ••• • •••••• 38 School prayer ••• • •••• 38-39 JERRY FALWELL Bakker scandal ........... •••• 48-49 Bishop Desmond Tutu •• • ••• 39 PTL • ••..••.•.••••••. • 44-45 JIMMY SWAGGART Bakker scandal .• .41-43 Fundraising •. .45 Israel. •• 49 Jews •••• • ••• 40 JAMES ROBISON Media • ...••.•.•.•••.................•••••..•.......•....... 44 THE 700 CLUB March 6, 1987 MOBILE, AL Reverend Pat Robertson: "For years, many Christian parents have thought that the public ~chools were teaching humanistic values that were quite different from what they wanted their children to learn. Now the concept of humanism and the humanities is very noble. To be humanitarianism (sic) is good. But secular humanism is actually a type of religion. It's actually atheism in a new guise. Well, in Mobile, Alabama, 624 parents decided to do something about it. They were joined of course in that part of the 624 were teachers and students." NARRATOR: "It may go down as the religious liberty case of the twentieth century ••• The decision marks the first time, humanism, including secular humanism, has been recognized and defined as a religion. That means it can no longer be allowed a preferred position in public education but now, legally, will have to be treated with strict neutrality, as required of all religions by the Supreme Court." Attorney for the Plaintiffs, Tom Parker: "Not only does this decision ban the use of certain books in the state of Alabama which violate Constitutional rights, it also establishes some guidelines which could be used by state textbook committees or by concerned parents. -

Keli Edwards

Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 4, Issue 10 - July 2003 Televangelism and Political Ideology: A Study of Content and Ideology in The 700 Club Keli Edwards INTRODUCTION International Christian broadcasters play a significant role in the distribution of both ideological and religious messages and have attracted significant scholarly attention. By far, the international religious broadcaster that has received the most attention from scholars is the Christian Broadcasting Network and its flagship program, The 700 Club. The program has been described as a carrier of right-wing ideologies by several researchers who have examined its content (Gifford, 1991). Its creator, Pat Robertson has skillfully combined religion with politics to form a show that disseminates conservative opinion and news coverage on current events. A framing analysis of this program reveals the conservative political bias of the news stories, while a content analysis offers a numerical description of the extent to which program content deploys this ideology. This study will attempt to answer the following questions: 1) What are the salient content categories of the 700 Club program? 2) What ideologies (political, economic, cultural, religious and social) are emphasized in the 700 Club? METHOD The first step included the viewing and analysis of the 700 Club program for recurring themes and to identify the distinct segments of the show. Once these program segments were identified, a set of categories was created into which each of the program segments could be classified. One constructed sample week of 700 Club programming was selected and recorded for the pilot study. This constructed week included shows aired from May to November 2002, taking care not to repeat any day in the week. -

FOR Why Were You Rescued and Brought to Wildcare Eastern Sierra

The Inyo Register TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2020 7 MAN ON THE STREET Why were you rescued and brought to Wildcare Eastern Sierra for help? By Wildcare Eastern Sierra “A man rescued my “I was pulled from my “I was hunting near “I found an opening into “I saw a dead rabbit on “A few friends and I nest when he saw mom nest by a bird with a some buildings, chasing a big building where the side of the highway. were flying near Church had been killed. When sharp beak. I wiggled a mouse, and I fell in a someone kept leaving I flew down to take it and Fowler, looking for he took us to Wildcare, and it dropped me to pan full of motor oil. A some yummy snacks. away, but as I lifted up, food. I got into some it was time for me to the ground. My tummy person found me and One night they set a a truck ran into me. My kind of opening and break out of my egg. was bleeding. A person took me to Wildcare. A trap and I was caught. wing was injured. I could couldn’t get out. A per- Most of my brothers and found me and took me lot of Dawn baths will Wildcare came and, run but I couldn’t fly. A son saw me and went to sisters were hatching to her house where she make sure my feathers since I wasn’t hurt, sheriff and a volunteer the Police Department. too. I’m learning how to fed me and took care are clean.” they took me to a good from Wildcare caught They came and picked find food.” of me. -

(BP)--Southern Baptist Convention Presid

BUREAUS ATLANTA Walkar L. Knight. Chief. 1360 Spring St., N.W., Atlanta, Ga. 30309, Telephone (404) 873·4041 DALLAS ' Chief, 103 Baptist Building, Dallas, Tex. 76201, Telephone (214) 741·1996 MEMPHIS Roy Jennings Chief. 1648 poplar Ave., Memphis. Tenn. 38104, Telephone (901) 272-2461 NASHVILLE (Baptist SU~day School Board) , Chief. 127Ninth Ave., N., Nashville, Tenn. 37234, Telephone (616) 261-2798 RICHMOND Robert L. Stanley. Chief. 3806 Monument Ave., Richmond, Va. 23230. Telephone (804) 363·0161 WASHINGTON Stan L. Hastey. Chief. 200 Maryland Ave.• N.E., Washington, D.C. 20002, Telephone (202) 644-4226 January25,1980 80-16 Rogers Joins Group Urging Prayer in the Schools By Stan Hastey WASHINGlDN (BP) --Southern Baptist Convention President Adrian Rogers and at least four other Southern Baptist ministers have joined a larger group of conservative religious spokesmen urging removal of prayer in the schools from the jurisdiction of the federal courts. Official actions of the Southern Baptist Convention and the Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs, however, have upheld U.S. Supreme Court decisions in the past two decades oppos ing state-supported religion in public schools. Rogers, elected to a one-year term as SBC president last June in a tumultuous annual meeting of the 13.4-million-member SBC, said, "My involvement is as Adrian P. Rogers. Period. It's not as president of the Southern Baptist Convention or as pastor of Bellevue Baptist Church" in Memphis, Tenn. "'_.""',~",~.... ~, ...."" Also joining in as sponsors ofthe Coalition for the First Amendment were James Robison, evangel1st from Hurst, Texas; Paige Patterson, president of the Criswell Center for Biblical Studies, Dallas; Charles Stanley, pastor of First Baptist Church, Atlanta, Ga.; and Morri-s Sheats, pastor of Beverly Hills Baptist Church, Dallas. -

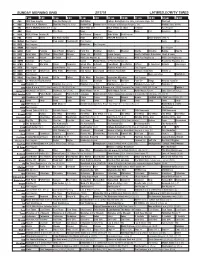

Sunday Morning Grid 2/17/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/17/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Ohio State at Michigan State. (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Day Hockey New York Rangers at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Hockey: Blues at Wild 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid American Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Planet Weird Fox News Sunday News PBC Face NASCAR RaceDay (N) 2019 Daytona 500 (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Grand Canyon Huell’s California Adventures: Huell & Louie 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Jeffress Win Walk Prince Carpenter Intend Min. -

I. Tv Stations

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) MB Docket No. 17- WSBS Licensing, Inc. ) ) ) CSR No. For Modification of the Television Market ) For WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida ) Facility ID No. 72053 To: Office of the Secretary Attn.: Chief, Policy Division, Media Bureau PETITION FOR SPECIAL RELIEF WSBS LICENSING, INC. SPANISH BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC. Nancy A. Ory Paul A. Cicelski Laura M. Berman Lerman Senter PLLC 2001 L Street NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (202) 429-8970 April 19, 2017 Their Attorneys -ii- SUMMARY In this Petition, WSBS Licensing, Inc. and its parent company Spanish Broadcasting System, Inc. (“SBS”) seek modification of the television market of WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida (the “Station”), to reinstate 41 communities (the “Communities”) located in the Miami- Ft. Lauderdale Designated Market Area (the “Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA” or the “DMA”) that were previously deleted from the Station’s television market by virtue of a series of market modification decisions released in 1996 and 1997. SBS seeks recognition that the Communities located in Miami-Dade and Broward Counties form an integral part of WSBS-TV’s natural market. The elimination of the Communities prior to SBS’s ownership of the Station cannot diminish WSBS-TV’s longstanding service to the Communities, to which WSBS-TV provides significant locally-produced news and public affairs programming targeted to residents of the Communities, and where the Station has developed many substantial advertising relationships with local businesses throughout the Communities within the Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA. Cable operators have obviously long recognized that a clear nexus exists between the Communities and WSBS-TV’s programming because they have been voluntarily carrying WSBS-TV continuously for at least a decade and continue to carry the Station today. -

Motion to Strike

GRIG(, ~~~AL BEFORE THE ggy4 1989 COPYRIGHT ROYALTY TRIBUNAL Washington, D.C. 20036 In the Matter of ) ) Docket No. CRT-89-2 87CD Distribution of 1987 ) Cable Royalty Fund ) ) MOTION TO STRIKE The Settling Devotional Claimants, through counsel, hereby move to strike the following parts of the Direct Case for Christian Television Corporation ("CTC"): A. Testimon of Robert T. Kenned 1. The last sentence of the third full paragraph on page 2 should be stricken. The sentence reads as follows: we increased our cable coverage 62% (from January to November, 1987)." This statement lumps together carriage of CTC's programs on both local and distant signals. It is irrelevant to the Tribunal's determination concerning the marketplace value of CTC's programs solely on distant broadcast signals. Indeed, the sentence tends to confuse the issues by failing to distinguish local from distant signal carriage, and should therefore be stricken from testimony presented to the Tribunal. 2. The last sentence of the fourth full paragraph on page 4 should be stricken. The sentence reads: "CTC programming is a special benefit in that, we offer 168 hours of Christian programming per week, 46-1/2 hours of which is CTC-produced original programming." (emphases omitted). This statement does not report cable carriage of distant signals. Rather, it relates either to carriage of CTC's programs on CTC's own satellite network or to carriage on CTC's own broadcast station. The amount, of programming on the network and station have absolutely no bearing on the Tribunal's determination and should be stricken from the record. -

'GRAMMY Salute' on PBS Special

October 11 - 17, 2020 The Barre Montpelier Times Argus and Rutland Herald Other stars make music for ‘GRAMMY Salute’ on PBS special Jimmy Jam hosts “Great Performances: GRAMMY Salute to Music Legends” Friday on PBS (check local listings). Crosswords, Puzzles & More BY JAY BOBBIN BY JAY BOBBIN The wait is over for a A new ‘GRAMMY Salute to Music new season of Legends’ honors John Prine, ‘The Amazing Race’ Chicago and others The “Race” is on again, though it’s taken a bit longer than expected this time. Phil Keoghan The 32nd season of CBS’ Emmy-winning The late John “The Amazing Race” originally was slated Prine is among to premiere last spring, but ended up being With so many restrictions on travel, Keoghan those honored delayed – likely to keep it available for a fall believes the literally globe-trotting “Amazing on “Great season when the network’s programming Race” serves an extra purpose this time. Performances: plans would be impacted by the coronavirus “It’s great for us,” he reasons, “to be able to GRAMMY pandemic. The Phil Keoghan-hosted provide some escapism for viewers who can Salute to Music competition’s latest round finally begins airing travel vicariously around the world from the Legends” Wednesday, Oct. 14. comfort of their living rooms. We love that we Friday on PBS “I think the timing of this is perfect,” have the show ready to go, and that people can maintains the friendly Keoghan, also an enjoy it at a time that’s really challenging for “Amazing Race” executive producer. “Mental them.” health is such an important part of us all Keoghan hasn’t been missing from screens Each year, several music icons get a special Jimmy Jam notes he has “some connection” getting through this (pandemic), and ironically, completely in recent months: The summer tribute from the organization that presents the to every artist celebrated on the show, “because there have been some really positive things that contest he initiated, “Tough as Nails,” has Grammy Awards – and, at least in that respect, that’s the great thing about what music does. -

Laying Hands on Religious Racketeers: Applying Civil RICO to Fraudulent Religious Solicitation

William & Mary Law Review Volume 29 (1987-1988) Issue 3 Article 2 April 1988 Laying Hands on Religious Racketeers: Applying Civil RICO to Fraudulent Religious Solicitation Jonathan Turley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Jonathan Turley, Laying Hands on Religious Racketeers: Applying Civil RICO to Fraudulent Religious Solicitation, 29 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 441 (1988), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/ vol29/iss3/2 Copyright c 1988 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr William and Mary Law Review VOLUME 29 SPRING 1988 NUMBER 3 LAYING HANDS ON RELIGIOUS RACKETEERS: APPLYING CIVIL RICO TO FRAUDULENT RELIGIOUS SOLICITATION JONATHAN TURLEY* CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... 443 II. RELIGIOUS TELEVISION SOLICITATION: SHOULD THE ELEVENTH COMMANDMENT BE 'CAVEAT EMPTOR'? . 447 A. General Solicitation Fraud ................... 455 B. Goal-Specific Solicitation Fraud .............. 459 III. PRIVATE AND GOVERNMENTAL REMEDIES FOR RELIGIOUS FRAUD .......................................... 463 A. Private Enforcement ....................... 465 B. Governmental Enforcement .................. 468 1. The Federal Communications Commission: "Plugged into Heaven".................. 468 2. The Internal Revenue Service: Rendering unto Caesar ............................ 470 3. Political and PracticalProblems of Govern- mental Deterrence ...................... 474 * Federal Judicial Clerk, United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. J.D., Northwestern University School of Law, 1987; B.A., University of Chicago, 1983. I wish to thank Thomas Eovaldi for his encouragement at various stages of this research. The respon- sibility, however, for all theories and conclusions in this Article is entirely the author's. 442 WILLIAM AND MARY LAW REVIEW [Vol. -

A Descriptive Analysis of the Current Status of Paid Religious Broadcasting on National Television

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1984 A Descriptive Analysis of the Current Status of Paid Religious Broadcasting on National Television Wayne R. Bills Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Mormon Studies Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, and the Television Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Bills, Wayne R., "A Descriptive Analysis of the Current Status of Paid Religious Broadcasting on National Television" (1984). Theses and Dissertations. 4533. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4533 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. faiF ioZI10101.004 f A desceDESCRdescriptivejprcprivilivinivanivln ANALYSISANALYSES OFCA tyl11111111 CURIZENTrifcliPRENT STATUSSTAFUSOPOFPAID RELIGIOUS broadcajtjngbroadcastingbroadcasiing ON NATIONALNA 1 ional10nal telltelitelevision1.1iVISION A thesischesjhes is presentedre sentted to theuhe depardepartbepartt melic ofoc communicationscommunicatcommunicate ionslons brigham young university jnitzilk partial fuP sirijuirijf lrenee n t of the rcpeququ i irenientsloincnty lotloifotfor lietiletiloLeieeleie degree mastermaslmast r olof01 artartsarte I1tyY alynwlyn I1I1 -

The 700 Club· 5-1-96

The 700 Club· 5-1-96 Newswatch: 1) Gas prices skyrocket as the President scrambles to drive them back down by selling off oil reserves. 2) A CBN report on how the Middle East peace process is moving along. A focus on the question of whether the Palestinians can be trusted. 3) A summit of unity between Christian and Jewish groups supporting the Jewish state of Israel. There was some talk of the distrust still felt for Arafat. 4) A rainy report from the last day at Washington for Jesus. 5) Hillary Clinton's fingerprints are on the famed Whitewater billing records. 6) A Southwest jetliner makes a dangerous emergency landing. 7) The baby born to a raped comatose woman leaves the hospital healthy. 8) New abortion laws signed into law in Wisconsin. 9) Freak storms rage in the midwest with snow and floods. 10) U.N. scientists say 1995 was the hottest year on record. Features: 1) The stunning story of police officer Gary Dockery and his family during their journey from his gunshot injury to his recent awakening from a coma. 2) Prayers. 3) Rerun story of a young man who tragically loses his three little girls to his estranged and unstable wife. 4) Another rerun, a story of a minister's daughter whose rocky path finally leads back to Jesus. The 700 Club 5-2-96 Newswatch: 1) Government reports show the country's economic health is surprisingly good. 2) A new immigration bill is working its way through the Senate. 3) Today marks the National Day of Prayer.