Abstract Certain Values, Norms and Customs Are Deeply Rooted in Our Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Books Details

1 Thumbnail Details A Brief History of Malayalam Language; Dr. E.V.N. Namboodiri The history of Malayalam Language in the background of pre- history and external history within the framework of modern linguistics. The author has made use of the descriptive analysis of old texts and modern dialects of Malayalam prepared by scholars from various Universities, which made this study an authoritative one. ISBN : 81-87590-06-08 Pages: 216 Price : 130.00 Availability: Available. A Brief Survey of the Art Scenario of Kerala; Vijayakumar Menon The book is a short history of the painting tradition and sculpture of Kerala from mural to modern period. The approach is interdisciplinary and tries to give a brief account of the change in the concept, expression and sensibility in the Art Scenario of Kerala. ISBN : 81-87590-09-2 Pages: 190 Price : 120.00 Availability: Available. An Artist in Life; Niharranjan Ray The book is a commentary on the life and works of Rabindranath Tagore. The evolution of Tagore’s personality – so vast and complex and many sided is revealed in this book through a comprehensive study of his life and works. ISBN : Pages: 482 Price : 30.00 Availability: Available. Canadian Literature; Ed: Jameela Begum The collection of fourteen essays on cotemporary Canadian Literature brings into focus the multicultural and multiracial base of Canadian Literature today. In keeping the varied background of the contributors, the essays reflect a wide range of critical approaches: feminist, postmodern, formalists, thematic and sociological. SBN : 033392 259 X Pages: 200 Price : 150.00 Availability: Available. 2 Carol Shields; Comp: Lekshmi Prasannan Ed: Jameela Begum A The monograph on Carol Shields, famous Canadian writer, is the first of a series of monographs that the centre for Canadian studies has designed. -

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: a Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: A Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels K. AYYAPPA PANIKER If marriages were made in heaven, the humans would not have much work to do in this world. But fornmately or unfortunately marriages continue to be a matter of grave concern not only for individuals before, during, and/ or after matrimony, but also for social and religious groups. Marriages do create problems, but many look upon them as capable of solving problems too. To the poet's saying about the course of true love, we might add that there are forces that do not allow the smooth running of the course of true love. Yet those who believe in love as a panacea for all personal and social ills recommend it as a sure means of achieving social and religious integration across caste and communal barriers. In a poem written against the backdrop of the 1921 Moplah Rebellion in Malabar, the Malayalam poet Kumaran Asan presents a futuristic Brahmin-Chandala or Nambudiri-Pulaya marriage. To him this was advaita in practice, although in that poem this vision of unity is not extended to the Muslims. In Malayalam fi ction, however, the theme of love and marriage between Hindus and Muslims keeps recurring, although portrayals of the successful working of inter-communal marriages are very rare. This article tries to focus on three novels in Malayalam in which this theme of Hindu-Muslim relationship is presented either as the pivotal or as a minor concern. In all the three cases love flourishes, but marriage is forestalled by unfavourable circumstances. -

K. Satchidanandan

1 K. SATCHIDANANDAN Bio-data: Highlights Date of Birth : 28 May 1946 Place of birth : Pulloot, Trichur Dt., Kerala Academic Qualifications M.A. (English) Maharajas College, Ernakulam, Kerala Ph.D. (English) on Post-Structuralist Literary Theory, University of Calic Posts held Consultant, Ministry of Human Resource, Govt. of India( 2006-2007) Secretary, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi (1996-2006) Editor (English), Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi (1992-96) Professor, Christ College, Irinjalakuda, Kerala (1979-92) Lecturer, Christ College, Irinjalakuda, Kerala (1970-79) Lecturer, K.K.T.M. College, Pullut, Trichur (Dt.), Kerala (1967-70) Present Address 7-C, Neethi Apartments, Plot No.84, I.P. Extension, Delhi 110 092 Phone :011- 22246240 (Res.), 09868232794 (M) E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Other important positions held 1. Member, Faculty of Languages, Calicut University (1987-1993) 2. Member, Post-Graduate Board of Studies, University of Kerala (1987-1990) 3. Resource Person, Faculty Improvement Programme, University of Calicut, M.G. University, Kottayam, Ambedkar University, Aurangabad, Kerala University, Trivandrum, Lucknow University and Delhi University (1990-2004) 4. Jury Member, Kerala Govt. Film Award, 1990. 5. Member, Language Advisory Board (Malayalam), Sahitya Akademi (1988-92) 6. Member, Malayalam Advisory Board, National Book Trust (1996- ) 7. Jury Member, Kabir Samman, M.P. Govt. (1990, 1994, 1996) 8. Executive Member, Progressive Writers’ & Artists Association, Kerala (1990-92) 9. Founder Member, Forum for Secular Culture, Kerala 10. Co-ordinator, Indian Writers’ Delegation to the Festival of India in China, 1994. 11. Co-ordinator, Kavita-93, All India Poets’ Meet, New Delhi. 12. Adviser, ‘Vagarth’ Poetry Centre, Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal. -

Festival of Letters 2014

DELHI Festival of Letters 2014 Conglemeration of Writers Festival of Letters 2014 (Sahityotsav) was organised in Delhi on a grand scale from 10-15 March 2014 at a few venues, Meghadoot Theatre Complex, Kamani Auditorium and Rabindra Bhawan lawns and Sahitya Akademi auditorium. It is the only inclusive literary festival in the country that truly represents 24 Indian languages and literature in India. Festival of Letters 2014 sought to reach out to the writers of all age groups across the country. Noteworthy feature of this year was a massive ‘Akademi Exhibition’ with rare collage of photographs and texts depicting the journey of the Akademi in the last 60 years. Felicitation of Sahitya Akademi Fellows was held as a part of the celebration of the jubilee year. The events of the festival included Sahitya Akademi Award Presentation Ceremony, Writers’ Meet, Samvatsar and Foundation Day Lectures, Face to Face programmmes, Live Performances of Artists (Loka: The Many Voices), Purvottari: Northern and North-Eastern Writers’ Meet, Felicitation of Akademi Fellows, Young Poets’ Meet, Bal Sahiti: Spin-A-Tale and a National Seminar on ‘Literary Criticism Today: Text, Trends and Issues’. n exhibition depicting the epochs Adown its journey of 60 years of its establishment organised at Rabindra Bhawan lawns, New Delhi was inaugurated on 10 March 2014. Nabneeta Debsen, a leading Bengali writer inaugurated the exhibition in the presence of Akademi President Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari, veteran Hindi poet, its Vice-President Chandrasekhar Kambar, veteran Kannada writer, the members of the Akademi General Council, the media persons and the writers and readers from Indian literary feternity. -

E-Newsletters, Publicity Materials Etc

DELHI SAHITYA AKADEMI TRANSLATION PRIZE PRESENTATION September 4-6, 2015, Dibrugarh ahitya Akademi organized its Translation Prize, 2014 at the Dibrugarh University premises on September 4-6, 2015. Prizes were presented on 4th, Translators’ Meet was held on 5th and Abhivyakti was held on S5th and 6th. Winners of Translation Prize with Ms. Pratibha Ray, Chief Guest, President and Secretary of Sahitya Akademi On 4th September, the first day of the event started at 5 pm at the Rang Ghar auditorium in Dibrugarh University. The Translation Prize, 2014 was held on the first day itself, where twenty four writers were awarded the Translation Prizes in the respective languages they have translated the literature into. Dr Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari, President, Sahitya Akademi, Eminent Odia writer Pratibha Ray was the chief guest, Guest of Honor Dr. Alak Kr Buragohain, Vice Chancellor, Dibrugarh University and Dr K. Sreenivasarao were present to grace the occasion. After the dignitaries addressed the gathering, the translation prizes were presented to the respective winners. The twenty four awardees were felicitated by a plaque, gamocha (a piece of cloth of utmost respect in the Assamese culture) and a prize of Rs.50, 000. The names of the twenty four winners of the translation prizes are • Bipul Deori won the Translation Prize in Assamese. • Benoy Kumar Mahanta won the Translation Prize in Bengali. • Surath Narzary won the Translation Prize in Bodo. • Yashpal ‘Nirmal’ won the Translation Prize in Dogri • Padmini Rajappa won the Translation Prize in English SAHITYA AKADEMI NEW S LETTER 1 DELHI • (Late) Nagindas Jivanlal Shah won the Translation Prize in Gujarati. -

Chemmeen Processed for Export: the Earliest Signs of Globalisation of the Word?

Chemmeen Processed for Export: The Earliest Signs of Globalisation of the Word? A.J.Thomas Abstract This paper attempts to analyse an English translation of Chemmeen, the Malayalam novel by Thakazhi Shivashankar pillai. Chemmeen has been translated into English by V.K Narayana Menon. A.J Thomas in this article examines Chemmeen as a piece of translation in a globalised world. Originating in Malayalam, the novel was an astonishing success in the world of translation. The article analyses the difficulties, delicacies and the indeterminacies of the translator in maintaining the authorial intention without any alterations. It articulates the strategies, the colonial or imperial and post-colonial impact on the translator in making the work of art a “best- seller.” The defence the translator mounts in omitting certain key passages and more importantly the deviation that the translated novel takes from the original seem to stem from the power equation between the two languages. Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai’s (Malayalam) novel Chemmeen , accepted as part of the UNESCO Collection of Representative Works - Indian Series, was translated by V.K.Narayana Menon, and published by Victor Gollancz, London in 1962. It was the first significant Malayalam novel to be translated into English after Independence or, rather, during the early post- colonial era. I have selected Chemmeen for detailed analysis for two reasons: One, this is the first Malayalam novel that captured the imagination of the rest of the world. Therefore the mechanics of its Translation Today Vol. 2 No. 2 Oct. 2005 © CIIL 2005 Chemmeen Processed for Export: The Earliest Signs of 41 Globalisation of the Word? translation, and its standing vis-à-vis the original, the points of departure it showed from the source text, the way linguistic and cultural problems were handled and resolved and so on would be of great interest. -

Translation Today Vol.2, No.2, October 2005

Editorial Policy ‘Translation Today’ is a biannual journal published by Central Institute of Indian Languages, Manasagangotri, Mysore. It is jointly brought out by Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, National Book Trust, India, New Delhi, and Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore. A peer- reviewed journal, it proposes to contribute to and enrich the burgeoning discipline of Translation Studies by publishing research articles as well as actual translations from and into Indian languages. Translation Today will feature full-length articles about translation- and translator-related issues, squibs which throw up a problem or an analytical puzzle without necessarily providing a solution, review articles and reviews of translations and of books on translation, actual translations, Letters to the Editor, and an Index of Translators, Contributors and Authors. It could in the future add new sections like Translators' job market, Translation software market, and so on. The problems and puzzles arising out of translation in general, and translation from and into Indian languages in particular will receive greater attention here. However, the journal would not limit itself to dealing with issues involving Indian languages alone. Translation Today • seeks a spurt in translation activity. • seeks excellence in the translated word. • seeks to further the frontiers of Translation Studies. • seeks to raise a strong awareness about translation, its possibilities and potentialities, its undoubted place in the history of ideas, and thus help catalyse a groundswell -

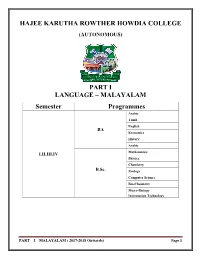

Hajee Karutha Rowther Howdia College Part I

HAJEE KARUTHA ROWTHER HOWDIA COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) PART I LANGUAGE – MALAYALAM Semester Programmes Arabic Tamil English BA Economics History Arabic I,II,III,IV Mathematics Physics Chemistry B.Sc. Zoology Computer Science Bio-Chemistry Micro-Biology Information Technology PART – I – MALAYALAM ( 2017-2018 Onwards) Page 1 Programme : UG Part : I Semester : I Hours : 6 Subject Code: 17UMLL11 Credit :3 HISTORY OF MALAYALAM LITERATURE COURSE OUTCOMES : CO1: It help to study poetry of the earth. CO2: Help to know about Manipravalam works. CO3: It help to study the growth of literary criticism Unit I Pattu, Manipravalam and Gaatha Unit II Ezhuthachan and his works, Vanchippattu and Tullal Unit III Folk songs, Brief history of kathakali and Attakkatha Unit IV Brief History of modern Malayalam poetry- Asan, Ulloor, Vallathole, Changanpuzha Krishnapillai, P. Kunjiraman Nair, G. Sankarakurup, Vylopilly sreedhara Menon, Edassery, Vayalar, P. Bhaskaran, O. N . V . Karup, sugathakumary, N.N. Kakkad, Balachandran Chullikkadu etc. Unit-V Brief account of Malayalam Novel, Short story, Drama Criticism and travelogue No text books prescribed Reference books 1. Kavitha Sahithya Charitram – Dr.M. Leelavathi (kerala sahithya Academy , Trichur) 2. Malayalam Novel Sahithya Charitram—K.M. Tharakan(N.B.S. kottayam) 3. Malayalam Nataka Sahithya Charitram—G.sankarapillai(D.C.Books,kottayam) 4. Cherukatha Innale Innu) —M.Achuyatham(D.C.Bokks,kottayam 5. Sahithya Charitram Prasathanagalilude—Dr.George, cheifEditor,D.C Books,kottayam PART – I – MALAYALAM ( 2017-2018 Onwards) Page 2 Programme : UG Part : I Semester : II Hours : 6 Subject Code : 17UMLL21 Credit :3 PROSE, COMPOSITION & TRANSLATION COURSE OUTCOMES: CO1:To understand the passage and grasp its meaning. -

(L.D. Clerk Re-Examination Idukki

11. Which one of the following is the source of energy in an eco system? (a) Light received from the sun (L.D. CLERK RE-EXAMINATION IDUKKI - 1999) (b) Sugar stored in plants (c) Heat liberated during fermentation of sugar (d) Heat liberated during respiration (e) None of these PART - I (MENTAL ABILITY) 12. Giri travelled 4 km. straight towards south. He turned left and travelled 6 km. This part contains 15 multiple choice items. Each question carries 1 mark straight; then turned right and travelled 4 km. straight. How far is he from the starting point 1. Five pairs of numbers are given. Find the one which is different from others (a) 8 km (b) 10 km (c) 12 (d) 18 km (e) 14 km (a) 55-42 (b) 69-56 (c) 48-34 (d) 95-82 (e) 78-65 13. Which of the following creature is not adapted to both aquatic and terrestrial life? 2. Find the word in the place of the question mark (a) Frog (b) Tortoise (c) Crocodile (d) Lizard (e) Crab Wax : Candle : : ? : Paper 14. RESISTANCE is to ohms as CURRENT is to (a) Tree (b) Bamboo (c) Pulp (d) Wood (e) Timber (a) Watts (b) Volts (c) Amperes (d) Litres (e) Joules 3. Find the one which is different from others 15. 6 is related to 18 in the same way as 4 is related to (a) 2 (b) 6 (c) 8 (d) 16 (a) 63 (b) 49 (c) 77 (d) 81 (e) 35 4. A train which is 1 km. long travelling at a speed of 60 km.per hour enters a tunnel 1 PART - II (GENERAL KNOWLEDGE) km. -

Details of Malayalam Books.Pmd

1 Thumbnail Details Àdhunikathayude Khadakangal Chithrakalayilum Novelilum Dr. Smitha Gopal A research work describing the influence of Modernism in novel and painting. Gives a detailed description of the new tendencies that has came in literature as well as in painting as a result of Modernism. It has got the first Bhashakkoru Dollar Puraskaram. ISBN : 81-86397-83-3 Pages: 200 Price : 120.00 Availability: Available Alankarasamkshepam Ed: S£ranad Kunjan Pillai Gives a detailed description of 28 figures of speeches, various metaphors and allied topics. Though an anonymous work, in value it is equivalent to Leelathilakam. Very useful for language lovers as well as scholars. Now it is the III edition of the same published by the Kerala University in 1954. ISBN : 81-86397-91-4 Pages: 48 Price : 30.00 Availability: Available A.R. Rajaraja Varma Dr. P.V. Velayudhan Pillai A.R. Rajaraja Varma was born in the year 1863 in Changanasseri Lakshmipuram Palace. Here Dr. P.V. Velayudhan Pillai gives a detailed account of his birth, childhood and his cotributions to Malayalam language. He was a poet, critic and prose writer, and his contributions to language are many. From this book we get a clear description of his multifaceted personality. It is one of the books included in the Malayalam Men of Letters Series. Pages: 94 Price : 20.00 Availability: Available Às°n Enna ·ilpi Nitya Chaitanya Yati Nitya Chaitanya Yati, the well known writer and spiritual preceptor objectively evaluates the poetic world of Mahakavi Kuamran Asan. He well describes the language speciality of his poems, his concepts and his philosophical thoughts. -

The Book of Job the Book of Job, Birds, Malayalam Literature, Kallur Raghavan, RV, Anandan, P

The Book of Job The Book of Job, birds, Malayalam Literature, Kallur Raghavan, RV, Anandan, P. Surendran, R. Gopalakrishnan, P. Surendran Sreekanth, Kerala, Malayalam poetry, colonial expansion, conservation of nature, ecological imperialism, European imperialism, ecological consciousness, paddy fields, Cheryll Glotfelty, Kerala legislative assembly, Joseph Beuys, Sara Joseph Radhika, Silent Valley Movement, Thrissur, Lord Shiva, Vishnu Narayanan Nambudiri, Kadamanitta Ramakrishnan, human beings, The Inheritors, environmental degradation, Kerala Sahitya Akademi Toward an uncivil society? Contextualizing the decline of post-Soviet Russian parties of the extreme right wing, Immigration and child and family policy, Deception, mystification, trauma: Laing and Freud, The 2009 horizon report: K, Elderly Americans, White civility and Aboriginal law/epistemology, Course Title Course Code INGL 3012, Comparative Stylistics, The plays of Girish Karnad and Vijay Tendulkar: A comparative study, Instructional technology and media for learning, The spectre on the stair: intertextual chains in'Great Expectations' and'The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Department of Cultural Affairs Govt of Kerala Kerala Sahitya Akademi ISSN 2319-3271 Kerala Sahitya Akademi 2014 June 2014 June ecology malayalam& literature Printed and published by R. Gopalakrishnan on behalf of Kerala Sahitya Akademi,Thrissur 680 020 and printed at Simple Printers, West Fort, Thrissur 680 004, Kerala and published at Thrissur, Thrissur Dist., Kerala State. Editor: R. Gopalakrishnan. MALAYALAM LITERARY SURVEY JUNE 2014 Special Issue on Ecology and Malayalam Literature KERALA SAHITYA AKADEMI Thrissur 680 020, Kerala Malayalam Literary Survey A Quarterly Publication of Kerala Sahitya Akademi, Thrissur Vol. 34 No. 1-2. 2014 Single Issue : Rs. 25/- This Issue - Rs. 50/- Annual Subscription : Rs. 100/- Editorial Board Perumbadavam Sreedharan - President R. -

Literary Movements in Malayalam During the Twentieth Century

Literary Movements in Malayalam During the Twentieth Century E.V. RAMAKRISHNAN Literary history, of late, has become a contested field of conflicting interests. Instead of tracing a linear progression of literary trends, this essay would explore the nature of the shifts in sensibility that obtain in the history of Malayalam writing during the course of the present century. I shall also examine whether the Nationalistic-Romantic phase of the early part of the century, the Progressivist Movement of the thirties and forties and the Modernist period of the sixties and seventies evidence certain common concerns that will enable us to comprehend the nature of conflicts that operate in Kerala society. My examples will be largely drawn from the fields of poetry and fiction. At the very outset, I would like to emphasise that to describe the paradigm shift in the history of literary sensibility is to interpret and evaluate its nature. The existing canon is largely an effect of the prevailing poetics. Each shift in sensibility redefines the canon in the process of projecting a new horizon of expectations for the reader and the author. The dynamics of literary forms and the. dialectic of socio-political changes together contribute to the definitions of literary history. Kumaran Asan (1873-1924) provides a convenient starting point because, besides being a major poet of the Romantic period, his name has been invoked both by the Progressivists and the Modernists at various points, to endorse their manner and substance of writing. In 1900 Asan was twenty seven years old when he returned to Trivandrum after spending three years in Bangalore and two years in Calcutta, having completed advanced training in Sanskrit and gained some proficiency in English.