Edinburgh Castle – New Barracks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Names Name Person(S)

The Names Name Person(s) Linkage/Connection/Background Fleming Linkage unknown. Old Hutch James Fleming Dair’s Margaret Cran (Dair) referred to her father’s nickname as ‘Old nickname. Hutch’, based on the character in a film. Old Hutch is a 1936 American romantic comedy film, a remake of the 1920 film Honest Hutch. Lambie Lambie was the second Linkage unknown. name of James Flemings younger sister Elisabeth. (Elisabeth Lambie Dair, b 1880, d 7 June 1945) Second name of Elizabeth (Bess) Lambie Dair Kinnear Kinnear was James Linkage unknown. Fleming Dair’s mother’s maiden name. (Helen Kinnear, b 22 July 1842 ) Second name of William (Bill) Kinnear Dair and Helen (Nel) Kinnear Grant Dair Grant Third name of Helen (Nel) Linkage unknown. Kinnear Grant Dair Cargill Cargill was the second Linkage unknown. name of James Fleming’s In Scottish history, few names go farther back than Cargill, eldest sister. whose ancestors lived among the clans of the Pictish tribe. (Jane Cargill Mustard Dair, They lived in the lands of Cargill in east Perthshire where the b 30 September 1873) family at one time had extensive territories. The surname Cargill was first found in Perthshire (Gaelic: Third name of Mary Jane Siorrachd Pheairt) former county in the present day Council Milne Cargill Dair Area of Perth and Kinross, located in central Scotland. Cargill is a parish containing, with the villages of Burreltown, Wolfhill, and Woodside. This place, of which the name, of Celtic origin, signifies a village with a church, originally formed a portion of the parish of Cupar-Angus, from which, according to ancient records, it was separated prior to the year 1514.1 Findlay Second name of Emily Linkage unknown. -

Waterloo 200

WATERLOO 200 THE OFFICIAL SOUVENIR PUBLICATION FOR THE BICENTENARY COMMEMORATIONS Edited by Robert McCall With an introduction by Major General Sir Evelyn Webb-Carter KCVO OBE DL £6.951 TheThe 200th Battle Anniversary of Issue Waterloo Date: 8th May 2015 The Battle of Waterloo The Isle of Man Post Offi ce is pleased 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man to celebrate this most signifi cant historical landmark MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 in collaboration with 75p 75p Waterloo 200. Isle of Man Isle of Man MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 SET OF 8 STAMPS MINT 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man TH31 – £6.60 PRESENTATION PACK TH41 – £7.35 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 FIRST DAY COVER 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man TH91 – £7.30 SHEET SET MINT TH66 – £26.40 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 FOLDER “The whole art of war consists of guessing at what is on the other side of the hill” TH43 – £30.00 Field Marshal His Grace The Duke of Wellington View the full collection on our website: www. iomstamps.com Isle of Man Stamps & Coins GUARANTEE OF SATISFACTION - If you are not 100% PO Box 10M, IOM Post Offi ce satisfi ed with the product, you can return items for exchange Douglas, Isle of Man IM99 1PB or a complete refund up to 30 days from the date of invoice. -

The History of the Second Dragoons : "Royal Scots Greys"

Si*S:i: \ l:;i| THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND DRAGOONS "Royal Scots Greys" THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND DRAGOONS 99 "Royal Scots Greys "•' •••• '-•: :.'': BY EDWARD ALMACK, F.S.A. ^/>/4 Forty-four Illustrations LONDON 1908 ^7As LIST OF SUBSCRIBERS. Aberdeen University Library, per P. J. Messrs. Cazenove & Son, London, W.C. Anderson, Esq., Librarian Major Edward F. Coates, M.P., Tayles Edward Almack, Esq., F.S.A. Hill, Ewell, Surrey Mrs. E. Almack Major W. F. Collins, Royal Scots Greys E. P. Almack, Esq., R.F.A. W. J. Collins, Esq., Royal Scots Greys Miss V. A. B. Almack Capt. H.R.H. Prince Arthur of Con- Miss G. E. C. Almack naught, K.G., G.C.V.O., Royal Scots W. W. C. Almack, Esq. Greys Charles W. Almack, Esq. The Hon. Henry H. Dalrymple, Loch- Army & Navy Stores, Ltd., London, S.W. inch, Castle Kennedy, Wigtonshire Lieut.-Col. Ash BURNER, late Queen's Bays Cyril Davenport, Esq., F.S.A. His Grace The Duke of Atholl, K.T., J. Barrington Deacon, Esq., Royal etc., etc. Western Yacht Club, Plymouth C. B. Balfour, Esq. Messrs. Douglas & Foulis, Booksellers, G. F. Barwick, Esq., Superintendent, Edinburgh Reading Room, British Museum E. H. Druce, Esq. Lieut. E. H. Scots Bonham, Royal Greys Second Lieut. Viscount Ebrington, Royal Lieut. M. Scots Borwick, Royal Greys Scots Greys Messrs. Bowering & Co., Booksellers, Mr. Francis Edwards, Bookseller, Lon- Plymouth don, W. Mr. W. Brown, Bookseller, Edinburgh Lord Eglinton, Eglinton Castle, Irvine, Major C. B. Bulkeley-Johnson, Royal N.B. Scots Greys Lieut. T. E. Estcourt, Royal Scots Greys 9573G5 VI. -

With Napoleon at Waterloo, and Other Unpublished Documents of The

,,>,!tfir^^^-:'iir}f^^-' r'' C7^ J WITH NAPOLEON AT WATERLOO / NAPOLEON From the marble medallion in the possession of the Editor Frontispiece WITH NAPOLEON AT WATERLOO AiND OTHER UNPUBLISHED DOCUMENTS OF THE; WATERLOO AND PENINSULAR CAMPAIGNS ALSO PAPERS ON WATERLOO BY THE LATE EDWARD BRUCE LOW M.A. EDITED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY MAC KENZIE MAC BRIDE WITH THIRTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON FRANCIS GRIFFITHS H MAIDEN LANE, STRAND, W.C. 1911 s iri / have to acknowledge my indebtedness for kind help to Mrs Ryde-Jones Alexander, Miss Fleming, Mr Robert T. Rose of Edinburgh, Mr Samuel Hales of Newmans Row, Lincoln Inn Fields, andtoM.^ George Preece the courteous chief Librarian of the Borough of Stoke Newing- ton. I believe the late Mr Bruce Low was indebted to Colonel Greenhill-Gardyne of Glenforsa for the loan of the diary of Sergt. Robertson.—Ed. 253027 — 1 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction . I With Abercrombie and Moore in Egypt. From THE Unpublished Diary of Sergeant Daniel NiCOL ..... 9 I. CAPTAIN LIVINGSTONE . II II. WHY THE BRITISH DID NOT TAKE CADIZ . 1 III. A TURKISH GOVERNOR . 20 IV. A HARD FOUGHT LANDING 25 V. THE GALLANT STAND OF THE 9OTH AT MANDORAH 29 VI. THE NIGHT ATTACK AT ALEXANDRIA 35 VII. A HOT MARCH . 4^ VIII. THE ENEMY RETIRE 47 IX. IN THE DESERT 52 X. ON THE BANKS OF THE NILE 57 XI. THE SIEGE OF ALEXANDRIA 63 CoRUNNA The Story of a Terrible Retreat From the Forgotten Journal of Sergeant D. Robertson I. THE MARCH TO BURGOS 71 II. HOW THEY CAPTURED A FRENCH PICQUET 76 III. -

East Ayrshire Council

1378 PLEASE NOTE THAT THE MINUTE REQUIRES TO BE APPROVED AS A CORRECT RECORD AT THE NEXT MEETING OF COUNCIL AND MAY BE AMENDED EAST AYRSHIRE COUNCIL MINUTES OF MEETING HELD ON THURSDAY 20 AUGUST 2015 AT 1000 HRS IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, COUNCIL HEADQUARTERS, LONDON ROAD, KILMARNOCK PRESENT: Provost Jim Todd and Councillors Ellen Freel, Eòghann MacColl, John McGhee, Helen Coffey, Elaine Cowan, Maureen McKay, Tom Cook, Lillian Jones, Iain Linton, Douglas Reid, Jim Buchanan, Depute Provost John Campbell, Councillors Gordon Cree, Drew McIntyre, John Knapp, Hugh Ross, George Mair, Bobby McDill, John McFadzean, Neil McGhee, Stephanie Primrose, Jim Roberts, David Shaw, Billy Crawford, Barney Menzies, Kathy Morrice, John Bell, Elaine Dinwoodie and Moira Pirie. ATTENDING: Fiona Lees, Chief Executive; Alex McPhee, Depute Chief Executive and Chief Financial Officer: Economy and Skills; Chris McAleavey, Depute Chief Executive: Safer Communities; Eddie Fraser, Director of Health and Social Care Partnership; Bill Walkinshaw, Head of Democratic Services; Stuart McCall, Legal Manager; Julie Haig, Public Relations Officer; and Julie McGarry, Administration Manager. ALSO ATTENDING: Jill Cronin, Head of Service: Ayrshire and Arran Tourism Team; John Griffiths, Chief Executive and Adam Geary, Cultural and Countryside Manager, East Ayrshire Leisure Trust; and Stewart Turner, Head of Roads: Ayrshire Roads Alliance. CHAIR: Provost Jim Todd, Chair. ADDITIONAL ITEM 1. The Provost advised of an additional item which he intended at Item Number 4. The Provost welcomed Kelly Kerr who was at East Ayrshire Council for two months working on a mini intern within the Legal Section before beginning her studies at Glasgow University. DEATH OF PAST PROVOST JANE DARNBROUGH 2. -

National Fund for Acquisitions Annual Report 2017–2018 1

National Fund for Acquisitions Annual Report 2017–2018 1 National Fund for Acquisitions Annual Report 2017–2018 2 Annual Report 2017–2018 National Fund for Acquisitions National Fund for Acquisitions Introduction The National Fund for Acquisitions (NFA), provided by the Scottish Government to the Board of Trustees of National Museums Scotland, contributes towards the acquisition of objects for the collections of Scottish museums, galleries, libraries, archives and other similar institutions open to the public. The Fund can help with acquisitions in most collecting areas including objects relating to the arts, literature, history, natural sciences, technology, industry and medicine. Decisions on grant applications are made following consultation with curatorial staff at National Museums Scotland, the National Galleries of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland who provide expert advice to the Fund. Funding The annual grant from the Scottish Government for 2017/18 was £150,000. During the year the National Fund for Acquisitions made 48 payments totalling £129,085 to 29 organisations. This included payment of grants which had been offered but not yet claimed at the end of the previous financial year. At 31 March 2018, a further 13 grants with a total value of £43,483 had been committed but not yet paid. The total purchase value of the objects to which the Fund contributed was £367,740. The Fund supported acquisitions for collections throughout Scotland, covering museum services in 17 of Scotland’s 32 local authority areas, including 13 local authority museum services, 10 independent museums and 6 university collections. Acknowledgement In partnership with our funder, the Scottish Government, we have introduced a logo to be used on all publicity and display associated with acquisitions supported by the National Fund for Acquisitions. -

THE WATERLOO SALE Wellington, Waterloo and the Napoleonic Wars Wednesday 1 April 2015

THE WATERLOO SALE Wellington, Waterloo and the Napoleonic Wars Wednesday 1 April 2015 THE WATERLOO SALE Wellington, Waterloo and the Napoleonic Wars Wednesday 1 April 2015, at 14.00 101 New Bond Street, London VIEWING Telephone bidding Silver CUSTOMER SERVICES Bidding by telephone will only Michael Moorcroft Monday to Friday 08.30 to 18.00 Be accepted on lots with a lower +44 (0) 20 7393 3835 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 HIGHLIGHTS ONLY Estimate in excess of £1,000. [email protected] RUSI As a courtesy to intending Whitehall, Please note that bids should be Prints bidders, Bonhams will provide a London, SW1A 2ET submitted no later than 4pm on Michael Jette written Indication of the physical the day prior to the sale. New +44 (0) 20 7393 3941 condition of lots in this sale if a Thursday 26 March 2015 bidders must also provide proof [email protected] request is received up to 24 10.00 - 16.00 of identity when submitting bids. hours before the auction starts. Failure to do this may result in This written Indication is issued THE COMPLETE SALE your bid not being processed. Ceramics Fergus Gambon subject to Clause 3 of the Notice Bonhams +44 (0) 20 7468 8245 to Bidders. Live online bidding is available 101 New Bond Street, [email protected] London, W1S 1SR for this sale ILLUSTRATIONS Please email [email protected] Front cover: Lot 140 (detail) Arms Sunday 29 March 2015 with ‘live bidding’ in the subject David Williams Back cover: Lot 18 (detail) 11.00 - 15.00 line 48 hours before the auction +44 (0) 20 7393 3807 Inside front -

The Waterloo Journal

RLOO ASSO TE CIA WA T E IO H N T 18 15 THE WATERLOO JOURNAL Vol. 38 No. 1 Spring 2016 THE WATERLOO JOURNAL 4 Secretary’s Notes John Morewood 5 The Waterloo Association and Regional Groups Paul F. Brunyee 6 The St Paul’s Commemorative Service Lady Jane Wellesley 10 The Waterloo 200 Digital Legacy Sir Evelyn Webb Carter 12 The New Waterloo Despatch Peter Warwick 16 The New Generaton of Waterloo Students Paul F. Brunyee 17 A Novel Defence Gareth Glover 21 Trafalgar Night On Board HMS Trincomalee, 2016 Paul F. Brunyee 22 November Lecture - The Story of Henry Percy Clare Harding 25 Cavalie Mercer - 200 Hundred Year On Robert Pocock 27 William Crawley Yonge - A Personal Account Ian Yonge 31 Wellington’s Men Remembered Volume 2 David & Janet Bromley 32 How I Ended Up Charging the French Again John Deverell Officers of the Association President: His Grace the Duke of Wellington, OBE, DL 34 Battlefield Tour, May 2015 Paul F. Brunyee Deputy President: Marquess of Douro 36 General Sir William Bell K.C.B. (1788- 1873) Christopher Bourne-Arton Vice-Presidents: Sir Julian Paget, Bt 38 Unseen Waterloo Exhibiion at Somerset House Paul F. Brunyee Mr John S. White MA, BA (Hons), PGCE, FINS 40 Intelligence Paul Chamberlain Chairman: Major General Sir Evelyn Webb-Carter, KCVO, OBE, DL* Council Members: Lady Jane Wellesley,* Mrs Alice Berkeley, BA, FRSA, FINS 44 Events Suzanne Brunt Mrs Suzanne Brunt, Mrs Frances Loudon-Carver, BA Mr Tim Cooke, Mr Mick Crumplin MB, BS, FRCS*, FINS Mrs Carole Divall, MA, BA(Hons) Editor’s Note Brig. -

The Scots Greys at Waterloo: the Battle That Turned the Tide Adam Down

The Scots Greys at Waterloo: The Battle That Turned The Tide Adam Down ‘Scotland Forever’, Elizabeth Thompson ,Lady Butler, 1881 The Battle That Turned The Tide The morning of Sunday June 18, 1815 in the fields near Waterloo, present day Belgium, may have begun quietly enough, however this was soon to change. Within a matter of 2 The Scots Greys at Waterloo: The Battle That Turned The Tide Adam Down hours, one of the greatest military defeats, the Battle of Waterloo, would take place in which a group of soldiers, many of whom had never seen action on the battlefield before, would bring down one of the greatest modern generals, Napoleon Bonaparte. The Battle of Waterloo, which lasted for approximately ten hours, was the culmination of three days of action, from June 16 1815, when Napoleon invaded Belgium, until June 18 when he was defeated at Waterloo. On that fateful Sunday the French artillery, under Napoleon’s command, began firing on the combined British, Dutch, Belgian and German forces under the command of the Duke of Wellington. The three days of fighting were not, though, an isolated incident. They were, in fact, the result of more than twenty years of war in Europe and across the globe, beginning with the French Revolution of 1789. The stunning defeat of Napoleon and his army came at the hands of the Duke of Wellington and his combined British forces, which included a group of relatively young and inexperienced soldiers known as the Scots Greys, a regiment that was originally formed in the late 1600s. -

The Spoils of War. the French Eagles Taken by the British Heavy Cavalry

Waterloo: the spoils of war. The French eagles taken by the British heavy cavalry during the attack of the 1st corps. The capture of the eagle of the 105me régiment de ligne has been and still is subject of controversy about who actually took it. The discussion revolves around two persons: captain Alexander Kennedy Clark or corporal Francis Stiles. A week after the events, captain Kennedy Clark wrote to his sister: “I had the honour to stab the bearer of the 45th battalion of infantry and take the eagle which is now in London. It is a very handsome blue silk flag with a large gilt eagle on top of the pole with the wings spread.” Though a fresh testimony written not long after the events, Kennedy Clark’s letter contains two major errors. First of all, he did not take it from the 45th, but from the 105th regiment. Additionally, the flag was not blue all-over, but tricolour (blue, white and red), surmounted by an eagle. The inscription – embroidered in gold - in front read “105e régiment d’infanterie de ligne” and on the reverse is stated “Iena, Eylau, Eckmühl, Essling, Wagram.” The eagle was donated to the regiment by the empress Louise. 1 Five days after the battle colonel Clifton (then acting brigade commander) wrote to the acting cavalry commander, colonel Felton Hervey, in the following terms: “I have particularly to mention my entire satisfaction with the conduct of brevet-lieutenant-colonel Dorville, who succeeded to the command of the Royal Dragoons, as well as brigade major Radclyffe and captain Clark of that regiment, the latter of whom contributed in a great degree in capturing the eagle. -

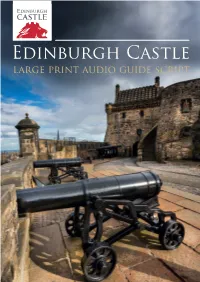

Edinburgh Castle Large Print Audio Guide Script Edinburgh Castle Large Print Audio Guide Script 1 – Argyle Battery / Welcome

Edinburgh Castle large print audio guide script Edinburgh Castle large print audio guide script 1 – Argyle Battery / Welcome VOICE MONTAGE [JAMES ROBERTSON; RACHAL PICKERING; DAVID ALLFREY; IAN RANKIN; HAZEL DUNN] My first memory of Edinburgh Castle was when I stepped off the sleeper from London at the age of six … It’s just fascinating and every single time I look at it, I see different elements … It’s on the top of a volcanic plug, it dominates the local landscape … You could come here 100 times and not get to the bottom of its wealth of stories … When you come out it’s always going to be a really good day if you’ve been at the Castle. SALLY MAGNUSSON Welcome to Edinburgh Castle, one of the world's most celebrated historic monuments and an iconic national landmark. EDDIE MAIR You’ve just walked onto the Argyle Battery through the Portcullis Gate – the main way into this stronghold for more than 2,000 years. You’re literally following in the footsteps of Iron Age warriors, medieval knights and Redcoat soldiers; of monarchs including Mary Queen of Scots and Robert the Bruce; and of American prisoners of war, giant medieval siege cannons ... and an elephant. History hangs heavy here. SALLY MAGNUSSON 2 I’m Eddie Mair. EDDIE MAIR And I’m Sally Magnusson. SALLY MAGNUSSON …And we’ll be exploring the castle with you today – experiencing the drama of its story through the words of those who lived it, and sharing the understanding of those who know the fortress best. EDDIE MAIR But before we begin, make sure your visit's a safe one.