The Implications of Brexit for the Good Friday Agreement: Key Findings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

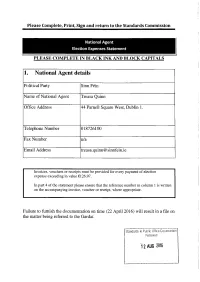

Sinn-Fein-NA-EES.Pdf

Candidate Name Constituency Amount Assigned Total Expenditure on the candidate by the national agent € € 1. Micheal MacDonncha Dublin Bay North 5000 2.Denise Mitchell Dublin Bay North 5000 3.Chris Andrews Dublin Bay South 5000 450.33 4.Mary Lou McDonald Dublin Central 4000 5.Louise O’Reilly Dublin Fingal 8000 2449.33 6. Eoin O’Broin Dublin Mid West 3000 7. Dessie Ellis Dublin North West 3000 8.Cathleen Carney Boud Dublin North West 5000 9.Sorcha Nic Cormaic Dublin Rathdown 5000 10.Aengus Ó Snodaigh Dublin South 3000 Central 11.Màire Devine Dublin South 3000 Central 12. Sean Crowe Dublin South West 3000 13.Sarah Holland Dublin South West 5000 14.Paul Donnelly Dublin West 3000 69.50 15.Shane O’Brien Dun Laoghaire 5000 73.30 16.Caoimhghìn Ó Caoláin Cavan Monaghan 3000 129.45 17.Kathryn Reilly Cavan Monaghan 3000 192.20 18.Pearse Doherty Donegal 3000 19.Pádraig MacLochlainn Donegal 3000 20.Garry Doherty Donegal 3000 21.Annemarie Roche Galway East 5000 22.Trevor O’Clochartaigh Galway West 5000 73.30 23.Réada Cronin Kildare North 5000 24.Patricia Ryan Kildare South 5000 13.75 25.Brian Stanley Laois 3000 255.55 26.Paul Hogan Longford 5000 Westmeath 27.Gerry Adams Louth 3000 28.Imelda Munster Louth 10000 29.Rose Conway Walsh Mayo 10000 560.57 30.Darren O’Rourke Meath East 6000 31.Peadar Tòibìn Meath West 3000 247.57 32.Carol Nolan Offaly 4000 33.Claire Kerrane Roscommon Galway 5000 34.Martin Kenny Sligo Leitrim 3000 193.36 35.Chris MacManus Sligo Leitrim 5000 36.Kathleen Funchion Carlow Kilkenny 5000 37.Noeleen Moran Clare 5000 794.51 38.Pat Buckley Cork East 6000 202.75 39.Jonathan O’Brien Cork North Central 3000 109.95 40.Thomas Gould Cork North Central 5000 109.95 41.Nigel Dennehy Cork North West 5000 42.Donnchadh Cork South Central 3000 O’Laoghaire 43.Rachel McCarthy Cork south West 5000 101.64 44.Martin Ferris Kerry County 3000 188.62 45.Maurice Quinlivan Limerick City 3000 46.Seamus Browne Limerick City 5000 187.11 47.Seamus Morris Tipperary 6000 1428.49 48.David Cullinane Waterford 3000 565.94 49.Johnny Mythen Wexford 10000 50.John Brady Wicklow 5000 . -

Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922

Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922 CONSTITUTION OF THE IRISH FREE STATE (SAORSTÁT EIREANN) ACT, 1922. AN ACT TO ENACT A CONSTITUTION FOR THE IRISH FREE STATE (SAORSTÁT EIREANN) AND FOR IMPLEMENTING THE TREATY BETWEEN GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND SIGNED AT LONDON ON THE 6TH DAY OF DECEMBER, 1921. DÁIL EIREANN sitting as a Constituent Assembly in this Provisional Parliament, acknowledging that all lawful authority comes from God to the people and in the confidence that the National life and unity of Ireland shall thus be restored, hereby proclaims the establishment of The Irish Free State (otherwise called Saorstát Eireann) and in the exercise of undoubted right, decrees and enacts as follows:— 1. The Constitution set forth in the First Schedule hereto annexed shall be the Constitution of The Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann). 2. The said Constitution shall be construed with reference to the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland set forth in the Second Schedule hereto annexed (hereinafter referred to as “the Scheduled Treaty”) which are hereby given the force of law, and if any provision of the said Constitution or of any amendment thereof or of any law made thereunder is in any respect repugnant to any of the provisions of the Scheduled Treaty, it shall, to the extent only of such repugnancy, be absolutely void and inoperative and the Parliament and the Executive Council of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) shall respectively pass such further legislation and do all such other things as may be necessary to implement the Scheduled Treaty. -

74 Dáil Éireann

(Second Supplementary Order Paper) 74 DÁIL ÉIREANN Dé Máirt, 1 Nollaig, 2020 Tuesday, 1st December, 2020 2 p.m. GNÓ COMHALTAÍ PRÍOBHÁIDEACHA PRIVATE MEMBERS' BUSINESS Fógra i dtaobh Leasú ar Thairiscint: Notice of Amendment to Motion [Please note: there is a change to the text of the Sinn Féin motion highlighted in bold on today’s Second Supplementary Order Paper.] 109. “That Dáil Éireann: notes that: — in five weeks’ time the pension age is due to increase to 67 years of age on 1st January, 2021; — legislation needed to stop the pension age increasing to 67 in January has not passed through the House; — every worker in the State makes a considerable tax contribution throughout their working life and should have the right to retire at 65; — some workers want to retire at 65, while others want to remain at work, where they are able and willing to do so; — numerous employment contracts stipulate an end of employment date in line with when an employee turns 65; — since the abolition of the State Pension Transition payment, thousands of 65-year olds have had to sign on for a Jobseeker’s payment; — there are now over 4,000 65-year olds in receipt of either Jobseeker’s Allowance or Jobseeker’s Benefit; — there is a difference of €45.30 between the Jobseeker payments and the State Pension leading to an annual loss of €2,355.60; and — the pension age is scheduled in legislation to increase to 67 years in 2021, and 68 years in 2028; and calls on the Government to: — restore the State Pension Transition payment for those retiring at 65 years of age; — abolish mandatory retirement (with exceptions for security-related employment) to give workers the choice to work or retire so long as they are fit to do so; P.T.O. -

"European Citizens Are Being Reminded"

02/02/2018 Gmail - "EUROPEAN CITIZENS ARE BEING REMINDED" William Finnerty <[email protected]> "EUROPEAN CITIZENS ARE BEING REMINDED" William Finnerty <[email protected]> Fri, Feb 2, 2018 at 3:45 PM To: UK Northern Ireland Secretary of State Karen Bradley MP <[email protected]>, "Northern Ireland Justice Department, Case Ref: COR/1248/2016" <[email protected]>, "First Minister of Northern Ireland Arlene Foster (Lawyer) LL.B. MLA" <[email protected]>, [email protected], Northern Ireland Justice Minister Claire Sugden MLA <[email protected]>, Northern Ireland Minister For Finance Máirtín Ó Muilleoir MLA <[email protected]>, Northern Ireland Minister for Health Michelle O'Neill MLA <[email protected]>, [email protected], "Discretionary Support Inspector D Todd at Office of Discretionary Support Commissioner, Belfast BT7 2JA" <[email protected]>, "Discretionary Support Commissioner, 20 Castle St, Antrim" <[email protected]>, NORTHERN IRELAND PENSION SERVICE <[email protected]>, "Welfare Adviser Damien O'Boyle at Ballynafeigh (Belfast) Community Development Association, Northern Ireland" <[email protected]>, Northern Ireland Southern Health and Social Care Trust SAFEGUARDING ADULTS TEAM <[email protected]>, "E&L Kennedy Law Firm, Belfast" <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Paul J. O'Kane LL.B." <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Aoife McShane LL.B." <[email protected]>, Lawyer Rory McShane <[email protected]>, Lawyer Mary Doherty <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Ronan McGuigan, LL.B. Solicitor Advocate" <[email protected]>, "Lawyer Jacqueline Malone LL.B. -

Prohibition of Conversion Therapies Bill 2018

An Bille um Thoirmeasc ar Theiripí Tiontúcháin, 2018 Prohibition of Conversion Therapies Bill 2018 Mar a tionscnaíodh As initiated [No. 33.6 of 2018] AN BILLE UM THOIRMEASC AR THEIRIPÍ TIONTÚCHÁIN, 2018 PROHIBITION OF CONVERSION THERAPIES BILL 2018 Mar a tionscnaíodh As initiated CONTENTS Section 1. Interpretation 2. Prohibition of Conversion Therapy 3. Criminalisation of Conversion Therapies 4. Short title and Commencement [No.33.6 of 2018] ACT REFERRED TO Mercantile Marine Act 1955 (No. 29) 2 AN BILLE UM THOIRMEASC AR THEIRIPÍ TIONTÚCHÁIN, 2018 PROHIBITION OF CONVERSION THERAPIES BILL 2018 Bill entitled An Act to prohibit conversion therapy, as a deceptive and harmful act or practice against 5 a person’s sexual orientation, gender identity and, or gender expression. Be it enacted by the Oireachtas as follows: Interpretation 1. In this Act— “conversion therapy”— 10 (a) means any practice or treatment by any person that seeks to change, suppress and, or eliminate a person’s sexual orientation, gender identity and, or gender expression; and (b) does not include any practice or treatment, which does not seek to change a person’s sexual orientation, gender identity and, or gender expression, or 15 which— (i) provides assistance to an individual undergoing a gender transition; or (ii) provides acceptance, support and understanding of a person, or a facilitation of a person’s coping, social support and identity exploration and development, including sexual orientation-neutral interventions; 20 “sexual orientation” refers to each person’s capacity -

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2. Malik Ben Achour, PS, Belgium 3. Tina Acketoft, Liberal Party, Sweden 4. Senator Fatima Ahallouch, PS, Belgium 5. Lord Nazir Ahmed, Non-affiliated, United Kingdom 6. Senator Alberto Airola, M5S, Italy 7. Hussein al-Taee, Social Democratic Party, Finland 8. Éric Alauzet, La République en Marche, France 9. Patricia Blanquer Alcaraz, Socialist Party, Spain 10. Lord John Alderdice, Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom 11. Felipe Jesús Sicilia Alférez, Socialist Party, Spain 12. Senator Alessandro Alfieri, PD, Italy 13. François Alfonsi, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (France) 14. Amira Mohamed Ali, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Group, Die Linke, Germany 15. Rushanara Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 16. Tahir Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 17. Mahir Alkaya, Spokesperson for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Socialist Party, the Netherlands 18. Senator Josefina Bueno Alonso, Socialist Party, Spain 19. Lord David Alton of Liverpool, Crossbench, United Kingdom 20. Patxi López Álvarez, Socialist Party, Spain 21. Nacho Sánchez Amor, S&D, European Parliament (Spain) 22. Luise Amtsberg, Green Party, Germany 23. Senator Bert Anciaux, sp.a, Belgium 24. Rt Hon Michael Ancram, the Marquess of Lothian, Former Chairman of the Conservative Party, Conservative Party, United Kingdom 25. Karin Andersen, Socialist Left Party, Norway 26. Kirsten Normann Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 27. Theresa Berg Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 28. Rasmus Andresen, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (Germany) 29. Lord David Anderson of Ipswich QC, Crossbench, United Kingdom 30. Barry Andrews, Renew Europe, European Parliament (Ireland) 31. Chris Andrews, Sinn Féin, Ireland 32. Eric Andrieu, S&D, European Parliament (France) 33. -

Bordering Two Unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics de Mars, Sylvia; Murray, Colin; O'Donoghue, Aiofe; Warwick, Ben Book — Published Version Bordering two unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit Policy Press Shorts: Policy & Practice Provided in Cooperation with: Bristol University Press Suggested Citation: de Mars, Sylvia; Murray, Colin; O'Donoghue, Aiofe; Warwick, Ben (2018) : Bordering two unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit, Policy Press Shorts: Policy & Practice, ISBN 978-1-4473-4622-7, Policy Press, Bristol, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv56fh0b This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190846 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen -

Lettre Conjointe De 1.080 Parlementaires De 25 Pays Européens Aux Gouvernements Et Dirigeants Européens Contre L'annexion De La Cisjordanie Par Israël

Lettre conjointe de 1.080 parlementaires de 25 pays européens aux gouvernements et dirigeants européens contre l'annexion de la Cisjordanie par Israël 23 juin 2020 Nous, parlementaires de toute l'Europe engagés en faveur d'un ordre mondial fonde ́ sur le droit international, partageons de vives inquietudeś concernant le plan du president́ Trump pour le conflit israeló -palestinien et la perspective d'une annexion israélienne du territoire de la Cisjordanie. Nous sommes profondement́ preoccuṕ eś par le preć edent́ que cela creerait́ pour les relations internationales en geń eral.́ Depuis des decennies,́ l'Europe promeut une solution juste au conflit israeló -palestinien sous la forme d'une solution a ̀ deux Etats,́ conformement́ au droit international et aux resolutionś pertinentes du Conseil de securit́ e ́ des Nations unies. Malheureusement, le plan du president́ Trump s'ecarté des parametres̀ et des principes convenus au niveau international. Il favorise un controlê israelień permanent sur un territoire palestinien fragmente,́ laissant les Palestiniens sans souverainete ́ et donnant feu vert a ̀ Israel̈ pour annexer unilateralement́ des parties importantes de la Cisjordanie. Suivant la voie du plan Trump, la coalition israelienné recemment́ composeé stipule que le gouvernement peut aller de l'avant avec l'annexion des̀ le 1er juillet 2020. Cette decisioń sera fatale aux perspectives de paix israeló -palestinienne et remettra en question les normes les plus fondamentales qui guident les relations internationales, y compris la Charte des Nations unies. Nous sommes profondement́ preoccuṕ eś par l'impact de l'annexion sur la vie des Israelienś et des Palestiniens ainsi que par son potentiel destabilisateuŕ dans la regioń aux portes de notre continent. -

Seanad Éireann

SEANAD ÉIREANN AN BILLE UM GHNÍOMHÚ AERÁIDE AGUS UM FHORBAIRT ÍSEALCHARBÓIN (LEASÚ), 2021 CLIMATE ACTION AND LOW CARBON DEVELOPMENT (AMENDMENT) BILL 2021 LEASUITHE COISTE COMMITTEE AMENDMENTS [No. 39a of 2021] [2 July, 2021] SEANAD ÉIREANN AN BILLE UM GHNÍOMHÚ AERÁIDE AGUS UM FHORBAIRT ÍSEALCHARBÓIN (LEASÚ), 2021 —AN COISTE CLIMATE ACTION AND LOW CARBON DEVELOPMENT (AMENDMENT) BILL 2021 —COMMITTEE STAGE Leasuithe Amendments *Government amendments are denoted by an asterisk SECTION 3 1. In page 6, line 29, after “emissions” to insert “minus removals”. —Senators Regina Doherty, Garret Ahearn, Paddy Burke, Jerry Buttimer, Maire Ní Bhroinn, Micheál Carrigy, Martin Conway, John Cummins, Emer Currie, Aisling Dolan, Seán Kyne, Tim Lombard, John McGahon, Joe O'Reilly, Mary Seery Kearney, Barry Ward, Lisa Chambers, Catherine Ardagh, Niall Blaney, Malcolm Byrne, Pat Casey, Shane Cassells, Lorraine Clifford-Lee, Ollie Crowe, Paul Daly, Aidan Davitt, Timmy Dooley, Mary Fitzpatrick, Robbie Gallagher, Gerry Horkan, Erin McGreehan, Eugene Murphy, Fiona O'Loughlin, Denis O'Donovan, Ned O'Sullivan, Diarmuid Wilson. 2. In page 6, to delete lines 34 and 35, and in page 7, to delete lines 1 to 3 and substitute the following: “ ‘climate justice’ means the requirement that decisions and actions taken, within the State and at the international level, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to adapt to the effects of climate change shall, in so far as it is practicable to do so— (a) support the people who are most affected by climate change but who have done the least to cause it and are the least equipped to adapt to its effects, (b) safeguard the most vulnerable persons, (c) endeavour to share the burdens and benefits arising from climate change, and (d) help to address inequality;”. -

Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999

TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased through any bookseller, or directly from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE, MOLESWORTH STREET, DUBLIN 2 £12.00 €15.24 © Copyright Government of Ireland 2000 ISBN 0-7076-6434-9 P. 33331/E Gr. 30-01 7/00 3,000 Brunswick Press Ltd. ii CLÁR CONTENTS Page Foreword........................................................................................................................................................................ v Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... vii LOCAL AUTHORITIES County Councils Carlow...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Cavan....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Clare ........................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Cork (Northern Division) .......................................................................................................................................... 19 Cork (Southern Division)......................................................................................................................................... -

Northern Ireland Assembiy

’^/rc'i . /■ ' ■: - '-.’f'. ■ ^. al IbeüPs^ Coiifirciís of líie United ^tírtcB Northern Ireland jta** K()5l|iiijitx]ii, BCC ?03l^ Assembiy Party), John Gilroy (Labour), 13 de Mayo, 2014 Washington^ miembro del Congreso (D), Donna F. Engel MP (Labour), Paul Farrclly Senator John Halligan TD (Independent), Londres, DuMín y Belfast Edwards, miembro dcl Congreso (D), MP (Labour), Jim Fitzpatrick MP Dominic Hannigan TD (Labour), 4.',“ Keith Ellison, miembro dcl Congreso (Labour), Rob Flcllo MP (Labour), MESA DE NEGOCIACIONE^ p), Elizabeth H. Esiy, miembro dcl Paul Flynn MP (Labour). Mikc Gapes Senador Jimmy Harte (Labour), DE LA HABANA Humberto de Congreso (D), Sam Farr, miembro del MP (Labour), Michelle Gildcrncw Senator Aideen Haydcn (Labour), la Calle y demás miembros de la Congreso (D). John Garamendi, miem MP (Sinn Fein), Andrew Gwynne MP Joe Higgins TD (Socíalist Party), Comisión Negociadora det Gobierno bro del Congreso (D), Raúl M. Grijalva, (Labour), Mike Hancock MP CBE Senador Lorraine Higgins (Labour), Brendan Howlin TD (Labour), Kevin de Cedombia miembro dcl Congreso (D), Luis V, (Indepcndenl Liberal Democrat), Iván Márquez y demás miembros Gutiérrez, miembro del Congreso Fabian Hamilton MP (Labour), Dai Humphreys TD (Labour), Alan Kelly de la Comisión Negociadora de las (D), Michacl M, Honda, miembro dcl Havard MP (Labour), Jimmy Hood TD (Labour), Senador John Kelly FARC-EP Congreso (D), Sheila Jackson Lee, MP (Labour), Kelvin Hopkins MP (Labour), Seán Kenny TD (Labour), miembro del Congreso (D), Henry (Labour), Martin Horwood -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84.