Non-State Nations: Structure, Rescaling, and the Role of Territorial Policy Communities, Illustrated by the Cases of Wales and Sardinia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Work Programme in Wales

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee The Work Programme in Wales Third Report of Session 2013–14 Volume I: Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Additional written evidence is contained in Volume II, available on the Committee website at www.parliament.uk/welshcom Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 22 October 2013 HC 264 Incorporating HC 999-i, Session 2012-13 Published on 4 November 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £15.50 The Welsh Affairs Committee The Welsh Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Office of the Secretary of State for Wales (including relations with the National Assembly for Wales). Current membership David T.C. Davies MP (Conservative, Monmouth) (Chair) Guto Bebb MP (Conservative, Aberconwy) Geraint Davies MP (Labour, Swansea West) Glyn Davies MP (Conservative, Montgomeryshire) Stephen Doughty MP (Labour, Cardiff South and Penarth) Jonathan Edwards MP (Plaid Cymru, Carmarthen East and Dinefwr) Nia Griffith MP (Labour, Llanelli) Simon Hart MP (Conservative, Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire) Mrs Siân C. James MP (Labour, Swansea East) Karen Lumley MP (Conservative, Redditch) Jessica Morden MP (Labour, Newport East) Mr Mark Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Ceredigion) The following Members were also members of the Committee during this Parliament Stuart Andrews MP (Conservative, Pudsey) Alun Cairns MP (Conservative, Vale of Glamorgan) Susan Elan Jones MP (Labour, Clwyd South) Owen Smith MP (Labour, Pontypridd) Robin Walker MP (Conservative, Worcester) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

Code of Guidance for Local Authorities

for Local Authorities on the Allocation of Accommodation and Homelessness March 2016 © Crown copyright 2016 WG28472 Digital ISBN: 978 1 4734 6395 0 Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymrae / This document is also available in Welsh. Code of Guidance Code CONTENTS Introduction About this Code of Guidance Purpose of the Code Target Audience Legal Status of the Code Structure of the Code Effective Dates of the Code Compliance with the Code The Legislation in Context Terminology Code up-dates Navigating the Code PART 1: ALLOCATIONS Chapter 1 Introduction Allocations and the Role of Social Landlords Improving Lives and Communities – Homes in Wales Housing White Paper, 2012 Communication Financial Inclusion Purpose of Part 1 of the Code Summary of Amendments to the Code Effective Date of Part 1 of Code Chapter 2 Eligibility for Housing Overview Definition of Allocation Eligible Categories Unacceptable Behaviour Policy Considerations Notification and Appeals to Decisions on Eligibility Residential Criteria Applications from Owner Occupiers No Fixed Address Chapter 3 The Allocations Scheme Balancing Priorities The Requirement to have an Allocation Scheme Transfer Applicants Civil Partnerships Joint Tenancies Succession Reasonable Preference Additional Preference Determining Priorities Choice and Preference Options Offers and Refusals Allocations Scheme Flexibility Meeting Diverse Needs Low Cost Home Ownership and Intermediate Rent Advice and Information Chapter 4 Allocation Scheme Management Housing Registers Allocations Scheme Consultation -

The Anatomy of Resilience: Helps and Hindrances As We Age

The anatomy of resilience: helps and hindrances as we age A review of the literature By Imogen Blood, Ian Copeman & Jenny Pannell October 2015 1 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all the people who gave up their time to talk to us about their personal circumstances and share with us their thoughts for the future. Thanks also go to the steering group for their direction and support: Cathryn Thomas (SSIA), Chris Davies (SSIA), Julie Boothroyd (Monmouthshire Adult Services), and Parry Davies (Ceredigion Adult Service). Rob Hutchinson also kindly shared the messages from his paper for SISG (the Strategic Improvement Steering Group) on Developing Early Intervention and Prevention for Older People. We would also like to acknowledge the input and support of the other members of our consortium – Jeremy Porteus of the Housing Learning & Improvement Network (LIN) who acted as a critical friend, and our associates at Miller Research who will be working with us to deliver the fieldwork phase of this study. 2 Contents Foreword 4 1. Introduction 5 1.2. Structure of this report 5 2. Developing a model to understand resilience 7 2.1. Overview of the qualitative research with older people 7 2.2. Links to outcomes and measures frameworks 8 2.3. The anatomy of resilience model 8 3. Findings from the review by theme 11 3.1. Relationships 11 3.2. Community 16 3.3. Finance 20 3.4. Health 24 3.5. Home 24 3.6. Psychological resources 30 3.7. Information 32 3.8. Work and learning 36 4. Understanding the crisis triggers 40 4.1. -

Final Local Government Finance Report 2015 to 2016 , File Type

LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE REPORT (NO.1) 2015-16 (Final Settlement - Councils) Welsh Ministers LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE REPORT (NO.1) 2015-16 (Final Settlement - Councils) 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE REPORT (NO.1) 2015-16 (Final Settlement - Councils) CONTENTS SECTION ONE - Purpose of report and main proposals Chapter 1: Purpose of report Chapter 2: Main proposals SECTION TWO - Councils Chapter 3: Calculation of the amount of Revenue Support Grant for each Council Chapter 4: Calculation of the amount of Non-Domestic Rates for each Council Chapter 5: Calculation of the Standard Spending Assessment for each Council SECTION THREE - Annexes to the Report Annex 1. Amounts of Revenue Support Grant to be paid to Specified Bodies Annex 2. Indicators and values used in the calculation of councils’ Standard Spending Assessments Annex 3. Glossary and Explanatory Notes Annex 4. Statutory Basis for the Report 2 LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE REPORT (NO.1) 2015-16 (Final Settlement - Councils) SECTION ONE: PURPOSE OF REPORT AND MAIN PROPOSALS Chapter 1: Purpose of report 1.1 This report is made in accordance with the requirements of the Local Government Finance Act 1988 (“the 1988 Act”). It sets out how much revenue support grant (RSG) the Welsh Ministers propose to distribute to county and county borough councils (hereafter referred to as councils) in Wales in 2015-16. The report also sets out how Non-Domestic Rates (NDR) will be distributed to councils and states the amount of RSG the Welsh Ministers propose to pay to specified bodies providing services to local government. 1.2 This report specifically relates to receiving authorities (other than Police and Crime Commissioners), and specified bodies. -

The Economic Significance of the Tidal Lagoon Swansea Bay

Tidal Lagoon Swansea Bay plc Appendix 22.1 Turning Tide: the economic significance of the Tidal Lagoon Swansea Bay Tidal Lagoon Swansea Bay – Environmental Statement Volume 3 Appendix 22.1 Turning Tide: the economic significance of the Tidal Lagoon Swansea Bay November 5th 2013 Prof Max Munday, Prof C Jones Welsh Economy Research Unit, Cardiff University Contact: Prof Max Munday Email: [email protected] Tel: 029 20 875089 w www.weru.org.uk t @WelshEcon TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 4 1.1 OUTLINE OF PROJECT .......................................................................................................... 4 1.2 OBJECTIVES ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT ............................................................................................... 5 2.0 ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT APPROACH ..................................................... 6 2.1 ANALYTICAL METHOD .......................................................................................................... 6 2.2 DIFFERENT TYPES OF REGIONAL ECONOMIC EFFECTS ........................................................... 8 2.3 MEASURES OF IMPACT ....................................................................................................... -

The Enabling State: Where Are We Now? Background Review of Policy Developments Reports 2013-2018 Jennifer Wallace (Editor) the Enabling State: Where Are We Now?

The Enabling State: Where are we now? Background Review of policy developments reports 2013-2018 Jennifer Wallace (Editor) The Enabling State: Where are we now? Enabling Wellbeing Policy Analysis The Enabling State: Where are we now? 2019 Acknowledgements The Carnegie UK Trust team on this project included: Jenny Brotchie, Natalie Hancox, Alison Manson, Rebekah Menzies and Issy Petrie. The team carried out the desk-based reviews for Scotland and Wales. The Northern Ireland review was carried out by Stratagem and the England Review carried out by Caroline Slocock and Steve Wyler. The reviews were then considered by the following experts prior to publication: • Scotland: Sophie Flemig, Assistant Director & EC Fellow, Centre for Service Excellence (CenSE), University of Edinburgh • England: Rich Wilson, Director of OSCA • Wales: Emma Taylor- Collins, Senior Research Officer (Research, Analysis and Policy), Alliance for Useful Evidence • Northern Ireland: Karen Smyth, Head of Policy and Governance, Northern Ireland Local Government Association We are grateful to all the contributors for the time and effort they have put into this publication The text of this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license visit, http://creativecommons.org/licenses by-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. B Contents 1. Introduction and methodology 2 4. Scotland 70 1.1 Methods 5 4.1 From target setting to outcomes -

State of Natural Resources Report Technical Annex to Support Chapter 3

The State of Natural Resources Report (SoNaRR): Assessment of the Sustainable Management of Natural Resources. Annex Technical Annex for Chapter 3 Natural Resources Wales Final Report Date www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk About Natural Resources Wales We look after Wales’ environment so that it can look after nature, people and the economy. Our air, land, water, wildlife, plants and soil – our natural resources - provide us with our basic needs, including food, energy, health and enjoyment. When cared for in the right way, they can help us to reduce flooding, improve air quality and provide materials for construction. They also provide a home for some rare and beautiful wildlife and iconic landscapes we can enjoy and which boost the economy. But they are coming under increasing pressure – from climate change, from a growing population and the need for energy production. We aim to find better solutions to these challenges and create a more successful, healthy and resilient Wales. www.naturalresourceswales.gov.uk Evidence at Natural Resources Wales Natural Resources Wales is an evidence based organisation. We seek to ensure that our strategy, decisions, operations and advice to Welsh Government and others are underpinned by sound and quality-assured evidence. We recognise that it is critically important to have a good understanding of our changing environment. We will realise this vision by: Maintaining and developing the technical specialist skills of our staff; Securing our data and information; Having a well resourced proactive programme of evidence work; Continuing to review and add to our evidence to ensure it is fit for the challenges facing us; and Communicating our evidence in an open and transparent way. -

Support for Armed Forces Veterans in Wales

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee Support for Armed Forces Veterans in Wales Second Report of Session 2012–13 Volume I Volume I: Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Additional written evidence is contained in Volume II, available on the Committee website at www.parliament.uk/welshcom Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 5 February 2013 HC 131 Incorporating HC 1812-i-ii, Session 2010-12 Published on 12 February 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £20.00 The Welsh Affairs Committee The Welsh Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Office of the Secretary of State for Wales (including relations with the National Assembly for Wales). Current membership David T.C. Davies MP (Conservative, Monmouth) (Chair) Guto Bebb MP (Conservative, Aberconwy) Geraint Davies MP (Labour, Swansea West) Glyn Davies MP (Conservative, Montgomeryshire) Stephen Doughty MP (Labour, Cardiff South and Penarth) Jonathan Edwards MP (Plaid Cymru, Carmarthen East and Dinefwr) Nia Griffith MP (Labour, Llanelli) Simon Hart MP (Conservative, Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire) Mrs Siân C. James MP (Labour, Swansea East) Karen Lumley MP (Conservative, Redditch) Jessica Morden MP (Labour, Newport East) Mr Mark Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Ceredigion) The following Members were also members of the Committee during this Parliament Stuart Andrews MP (Conservative, Pudsey) Alun Cairns MP (Conservative, Vale of Glamorgan) Susan Elan Jones MP (Labour, Clwyd South) Owen Smith MP (Labour, Pontypridd) Robin Walker MP (Conservative, Worcester) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

Draft National Development Framework

WG40429 Welsh Government Consultation Report Draft National Development Framework September 2020 Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown Copyright Our first national development framework will when published be called ‘Future Wales – The National Plan 2040’. This document was prepared prior to publication and uses the name ‘national development framework’ and ‘NDF’ throughout. For clarification the references to the national development framework in this document are taken to mean Future Wales – The National Plan 2040. 2 Contents Chapter Page 1 Introduction 4 2 Engagement and consultation 5 3 Structure of the Report 11 4 Summary of Consultation Responses and Welsh 13 Government response 5 Welsh Government Response to Climate Change, 207 Environment and Rural Affairs Committee 6 Welsh Government Response to Economy, Skills and 229 Infrastructure Committee 7 Integrated Sustainability Appraisal (ISA) and Habitat 235 Regulations Assessment (HRA) summaries 3 1. Introduction 1.1 The Planning (Wales) Act 2015 requires Welsh Ministers to produce a National Development Framework (NDF) setting out the policies of the Welsh Government in relation to the development and use of land in Wales. The NDF is also identified in the national strategy, Prosperity for All, as a key component of the Government’s commitment towards achieving sustainable growth and combatting climate change. 1.2 A key stage in the preparation of the NDF is the publication of a full draft. This draft was published and subject to public consultation between 7 August and 15 November 2019. 1.3 This consultation report summarises and analyses the feedback provided by respondents, sets out the Welsh Government’s response to these, and explains how the responses have influenced and led to proposed changes made to draft NDF policies. -

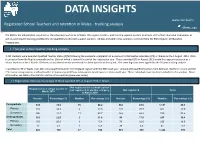

Data Insights

DATA INSIGHTS www.ewc.wales Registered School Teachers and retention in Wales - tracking analysis @ewc_cga The EWC is the independent regulator for the education workforce in Wales. We register teachers and learning support workers in schools and further education institutions, as well as work-based learning practitioners and qualified youth/youth support workers. All data included in this summary is derived from the EWC Register of Education Practitioners. 1. Five year school teacher tracking analysis 1,424 students were awarded Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) following the successful completion of a course of initial teacher education (ITE) in Wales on the 1 August 2013. Data is extracted from the Register annually on the 1 March which is toward the end of the registration year. Those awarded QTS in August 2013 would first appear registered as a school teacher on the 1 March 2014 extract and therefore five year trend has been taken from this point. The same logic has been applied to the 10 year tracking analysis. In addition to ITE in Wales, over 200 newly qualified teacher from England register with the EWC each year. Around 100 qualified teachers from Scotland, Northern Ireland and the EEA receive recognition as a school teacher in Wales or gain QTS via employment based routes in Wales each year. These individuals have not been included in this analysis. More information available in the statistics section of our website (www.ewc.wales). 1.1 Registration status by course type of those awarded QTS in August 2013 in Wales Not registered -

Chief Medical Officer for Wales Annual Report 2012-13

Chief Medical Officer for Wales Annual Report 2012-13 Healthier, Happier, Fairer Source: Visit Wales Acknowledgements I would like to thank colleagues from the Welsh Government for contributing to the development and editing of this report. Special thanks to Helen Jones, Hayley Jones and Benjamin Lewis for managing the production of the report, and also to Chris Brereton, David Hands, Suzanne Moore Osley, Dr Heather Payne, Dr Andrew Riley, Dr Chris Riley, Neil Riley, Cath Roberts, Chris Tudor-Smith and Alun Williams. I would also like to acknowledge the contribution made by colleagues in Public Health Wales in providing material and assisting with reviewing the report. WG18489 © Crown Copyright 2013 ISBN 978 1 4734 0301 7 Chief Medical Officer for Wales Annual Report 2012-13 Letter to the First Minister Dear First Minister, I am delighted to publish this, my first Annual Report as Chief Medical Officer for Wales. My role as a doctor at the heart of the Welsh Government gives me an opportunity to assess the health and wellbeing of the people of Wales and see where we might do better. While Wales has developed excellent initiatives and strong systems, this is a difficult time. The economic downturn is making life hard for many people, and that may take a toll on their health. There are no quick fixes for that and its shadow may be long. Against that backdrop, this report will not be restricted to an account of events in the last year. Instead it will set out an Source: Welsh Government assessment of where Wales stands with regard to health and wellbeing and what may lie ahead. -

(WALES) BILL Explanatory Memorandum

PLANNING (WALES) BILL Explanatory Memorandum Incorporating the Regulatory Impact Assessment and Explanatory Notes October 2014 1 2 Planning (Wales) Bill Explanatory Memorandum to the Planning (Wales) Bill This Explanatory Memorandum has been prepared by the Department for Sustainable Futures of the Welsh Government and is laid before the National Assembly for Wales. Member’s Declaration In my view, the Planning (Wales) Bill introduced by me on 6 October 2014 would be within the legislative competence of the National Assembly for Wales. Carl Sargeant AM Minister for Natural Resources Assembly Member in charge of the Bill October 2014 3 4 CONTENTS List of abbreviations PART 1 – Explanatory Memorandum 1. Description 2. Legislative background 3. Purpose and intended effect of the provisions 4. Consultation 5. Power to make subordinate legislation 6. Regulatory Impact Assessment PART 2 – Regulatory Impact Assessment 7. Options, costs and benefits 8. Competition assessment and specific impacts 9. Post implementation review PART 3 – Explanatory Notes 10. Explanatory Notes 11. Table of derivations Annex A – Cumulative Costs table 5 List of Abbreviations AMS – Annual Monitoring Schedule CIPFA – The Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy CRA - Commons Registration Authorities DAS – Design and Access Statements DCLG – Department for Communities and Local Government DEFRA – Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs DM – Development Management DNS – Developments of National Significance GDP – Gross Domestic Product GOWA