Depth Optimization Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Circulation and Water-Column Properties in The

Coastal Circulation and Water-Column Properties in the War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam— Measurements and Modeling of Waves, Currents, Temperature, Salinity, and Turbidity, April–August 2012 Open-File Report 2014–1130 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey FRONT COVER: Left: Photograph showing the impact of intentionally set wildfires on the land surface of War in the Pacific National Historical Park. Right: Underwater photograph of some of the healthy coral reefs in War in the Pacific National Historical Park. Coastal Circulation and Water-Column Properties in the War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam— Measurements and Modeling of Waves, Currents, Temperature, Salinity, and Turbidity, April–August 2012 By Curt D. Storlazzi, Olivia M. Cheriton, Jamie M.R. Lescinski, and Joshua B. Logan Open-File Report 2014–1130 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2014 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Suggested citation: Storlazzi, C.D., Cheriton, O.M., Lescinski, J.M.R., and Logan, J.B., 2014, Coastal circulation and water-column properties in the War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam—Measurements and modeling of waves, currents, temperature, salinity, and turbidity, April–August 2012: U.S. -

Hydrothermal Vent Fields and Chemosynthetic Biota on the World's

ARTICLE Received 13 Jul 2011 | Accepted 7 Dec 2011 | Published 10 Jan 2012 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms1636 Hydrothermal vent fields and chemosynthetic biota on the world’s deepest seafloor spreading centre Douglas P. Connelly1,*, Jonathan T. Copley2,*, Bramley J. Murton1, Kate Stansfield2, Paul A. Tyler2, Christopher R. German3, Cindy L. Van Dover4, Diva Amon2, Maaten Furlong1, Nancy Grindlay5, Nicholas Hayman6, Veit Hühnerbach1, Maria Judge7, Tim Le Bas1, Stephen McPhail1, Alexandra Meier2, Ko-ichi Nakamura8, Verity Nye2, Miles Pebody1, Rolf B. Pedersen9, Sophie Plouviez4, Carla Sands1, Roger C. Searle10, Peter Stevenson1, Sarah Taws2 & Sally Wilcox11 The Mid-Cayman spreading centre is an ultraslow-spreading ridge in the Caribbean Sea. Its extreme depth and geographic isolation from other mid-ocean ridges offer insights into the effects of pressure on hydrothermal venting, and the biogeography of vent fauna. Here we report the discovery of two hydrothermal vent fields on theM id-Cayman spreading centre. The Von Damm Vent Field is located on the upper slopes of an oceanic core complex at a depth of 2,300 m. High-temperature venting in this off-axis setting suggests that the global incidence of vent fields may be underestimated. At a depth of 4,960 m on the Mid-Cayman spreading centre axis, the Beebe Vent Field emits copper-enriched fluids and a buoyant plume that rises 1,100 m, consistent with > 400 °C venting from the world’s deepest known hydrothermal system. At both sites, a new morphospecies of alvinocaridid shrimp dominates faunal assemblages, which exhibit similarities to those of Mid-Atlantic vents. 1 National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, UK. -

Part 3. Oceanic Carbon and Nutrient Cycling

OCN 401 Biogeochemical Systems (11.03.11) (Schlesinger: Chapter 9) Part 3. Oceanic Carbon and Nutrient Cycling Lecture Outline 1. Models of Carbon in the Ocean 2. Nutrient Cycling in the Ocean Atmospheric-Ocean CO2 Exchange • CO2 dissolves in seawater as a function of [CO2] in the overlying atmosphere (PCO2), according to Henry’s Law: [CO2]aq = k*PCO2 (2.7) where k = the solubility constant • CO2 dissolution rate increases with: - increasing wind speed and turbulence - decreasing temperature - increasing pressure • CO2 enters the deep ocean with downward flux of cold water at polar latitudes - water upwelling today formed 300-500 years ago, when atmospheric [CO2] was 280 ppm, versus 360 ppm today • Although in theory ocean surface waters should be in equilibrium with atmospheric CO2, in practice large areas are undersaturated due to photosythetic C-removal: CO2 + H2O --> CH2O + O2 The Biological Pump • Sinking photosynthetic material, POM, remove C from the surface ocean • CO2 stripped from surface waters is replaced by dissolution of new CO2 from the atmosphere • This is known as the Biological Pump, the removal of inorganic carbon (CO2) from surface waters to organic carbon in deep waters - very little is buried with sediments (<<1% in the pelagic ocean) -most CO2 will ultimately be re-released to the atmosphere in zones of upwelling - in the absence of the biological pump, atmospheric CO2 would be much higher - a more active biological pump is one explanation for lower atmospheric CO2 during the last glacial epoch The Role of DOC and -

Biological Oceanography - Legendre, Louis and Rassoulzadegan, Fereidoun

OCEANOGRAPHY – Vol.II - Biological Oceanography - Legendre, Louis and Rassoulzadegan, Fereidoun BIOLOGICAL OCEANOGRAPHY Legendre, Louis and Rassoulzadegan, Fereidoun Laboratoire d'Océanographie de Villefranche, France. Keywords: Algae, allochthonous nutrient, aphotic zone, autochthonous nutrient, Auxotrophs, bacteria, bacterioplankton, benthos, carbon dioxide, carnivory, chelator, chemoautotrophs, ciliates, coastal eutrophication, coccolithophores, convection, crustaceans, cyanobacteria, detritus, diatoms, dinoflagellates, disphotic zone, dissolved organic carbon (DOC), dissolved organic matter (DOM), ecosystem, eukaryotes, euphotic zone, eutrophic, excretion, exoenzymes, exudation, fecal pellet, femtoplankton, fish, fish lavae, flagellates, food web, foraminifers, fungi, harmful algal blooms (HABs), herbivorous food web, herbivory, heterotrophs, holoplankton, ichthyoplankton, irradiance, labile, large planktonic microphages, lysis, macroplankton, marine snow, megaplankton, meroplankton, mesoplankton, metazoan, metazooplankton, microbial food web, microbial loop, microheterotrophs, microplankton, mixotrophs, mollusks, multivorous food web, mutualism, mycoplankton, nanoplankton, nekton, net community production (NCP), neuston, new production, nutrient limitation, nutrient (macro-, micro-, inorganic, organic), oligotrophic, omnivory, osmotrophs, particulate organic carbon (POC), particulate organic matter (POM), pelagic, phagocytosis, phagotrophs, photoautotorphs, photosynthesis, phytoplankton, phytoplankton bloom, picoplankton, plankton, -

Interactive Comment on “Impacts of UV Radiation on Plankton Community Metabolism Along the Humboldt Current System” by N

Biogeosciences Discuss., 8, C2596–C2611, 2011 Biogeosciences www.biogeosciences-discuss.net/8/C2596/2011/ Discussions © Author(s) 2011. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribute 3.0 License. Interactive comment on “Impacts of UV radiation on plankton community metabolism along the Humboldt Current System” by N. Godoy et al. Anonymous Referee #3 Received and published: 23 August 2011 Review Impacts of UV radiation on plankton community metabolism along the Hum- boldt Current System by N. Godoy, A. Canepa, S. Lasternas, E. Mayol, S. RuÄsz-´ Halpern, S. AgustÄs,´ J. C. Castilla, and C. M. Duarte. Biogeosciences Discuss., 8, 5827–5848, 2011 General Comment This article reports experimental estimates of community metabolism assessed at 8 stations in the eastern south Pacific conducted during the Humboldt-2009 cruise on board RV Hesperides from 5 to 15 March 2009. An experimental evaluation of the ef- fect of UVB radiation on community metabolism is conducted. From few experiments the authors claim that UVB radiation suppressed net community production, result- ing in a dominance of heterotrophic communities in surface waters, compared to the C2596 prevalence of autotrophic communities inferred when materials, excluding UVB radia- tion, are used for incubation. They also claim that their results show that UVB radiation, which has increased greatly in the study area, may have suppressed net community production of the plankton communities, possibly driving plankton communities in the Southwest Pacific towards CO2 sources. The evidence provided in the manuscript is not sufficient to support the conclusions. The sampling is clearly too limited, both spatially and temporally, to extrapolate their results to the Humboldt Current System. -

Recent Developments of Exploration and Detection of Shallow-Water Hydrothermal Systems

sustainability Article Recent Developments of Exploration and Detection of Shallow-Water Hydrothermal Systems Zhujun Zhang 1, Wei Fan 1, Weicheng Bao 1, Chen-Tung A Chen 2, Shuo Liu 1,3 and Yong Cai 3,* 1 Ocean College, Zhejiang University, Zhoushan 316000, China; [email protected] (Z.Z.); [email protected] (W.F.); [email protected] (W.B.); [email protected] (S.L.) 2 Institute of Marine Geology and Chemistry, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung 804, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 Ocean Research Center of Zhoushan, Zhejiang University, Zhoushan 316000, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 21 August 2020; Accepted: 29 October 2020; Published: 2 November 2020 Abstract: A hydrothermal vent system is one of the most unique marine environments on Earth. The cycling hydrothermal fluid hosts favorable conditions for unique life forms and novel mineralization mechanisms, which have attracted the interests of researchers in fields of biological, chemical and geological studies. Shallow-water hydrothermal vents located in coastal areas are suitable for hydrothermal studies due to their close relationship with human activities. This paper presents a summary of the developments in exploration and detection methods for shallow-water hydrothermal systems. Mapping and measuring approaches of vents, together with newly developed equipment, including sensors, measuring systems and water samplers, are included. These techniques provide scientists with improved accuracy, efficiency or even extended data types while studying shallow-water hydrothermal systems. Further development of these techniques may provide new potential for hydrothermal studies and relevant studies in fields of geology, origins of life and astrobiology. -

Upper Ocean Hydrology of the Northern Humboldt Current System

Progress in Oceanography 165 (2018) 123–144 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Progress in Oceanography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pocean Upper ocean hydrology of the Northern Humboldt Current System at T seasonal, interannual and interdecadal scales ⁎ Carmen Gradosa, , Alexis Chaigneaub, Vincent Echevinc, Noel Domingueza a Instituto del MAR de PErú (IMARPE), Callao, Peru b Laboratoire d'Études en Géophysique et Océanographie Spatiale (LEGOS), Université de Toulouse, CNES, CNRS, IRD, UPS, Toulouse, France c Laboratoire d'Océanographie et de Climatologie: Expérimentation et Analyse Numérique (LOCEAN), LOCEAN-IPSL, IRD/CNRS/Sorbonnes Universités (UPMC)/MNHN, UMR 7159, Paris, France ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Since the 1960s, the Instituto del Mar del Perú (IMARPE) collected tens of thousands of in-situ temperature and North Humboldt Current System salinity profiles in the Northern Humboldt Current System (NHCS). In this study, we blend this unique database Hydrology with the historical in-situ profiles available from the World Ocean Database for the period 1960–2014 and apply Water masses a four-dimensional interpolation scheme to construct a seasonal climatology of temperature and salinity of the Seasonal variations NHCS. The resulting interpolated temperature and salinity fields are gridded at a high spatial resolution Geostrophic currents (0.1° × 0.1° in latitude/longitude) between the surface and 1000 m depth, providing a detailed view of the ENSO Interdecadal variability hydrology and geostrophic circulation of this region. In particular, the mean distribution and characteristics of the main water-masses in the upper ocean of the NHCS are described, as well as their seasonal variations be- tween austral summer and winter. -

Primary Production and Community Respiration in the Humboldt Current System Off Chile and Associated Oceanic Areas

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published May 12 Mar Ecol bog Ser Primary production and community respiration in the Humboldt Current System off Chile and associated oceanic areas Giovanni Daneril-: Victor Dellarossa2, Renato ~uinones~,Barbara Jacob', Paulina ~ontero',Osvaldo Ulloa4 '~entrode Ciencias y Ecologia Aplicada (CEA), Universidad del Mar. Campus Valparaiso, Carmen 446, Placeres, Valparaiso. Chile 'Departamento de Boanica, 3~epartamentode OceanograKa and 'Programs Regional de Oceanografia Fisica y Clima. Universidad de Concepcion, Casilla 2407, Concepcion, Chile ABSTRACT: The hlgh biological productivity of the Hurnboldt Current System (HCS) off Chile sup- ports an annual fish catch of over 7 mill~ont. The area is also important biogeochemically, because the outgassing of recently upwelled water is modulated by contrasting degrees of biolopcal activity. How- ever, very few field measurements of primary production and planktonic respiration have been under- taken within the Eastern Boundary Current (EBC)system off Chile. In this study an estimate of primary production (PP) and surface planktonic commun~tyrespiration is presented from several research cruises in the HCS and adjacent oceanlc areas. The highest production levels were found near the coast correlating closely with known upwelling areas. Both gross primary production (GPP) and community respiration (CR) showed important spatial and temporal fluctuations. The highest water column inte- grated GPP was measured in the southern and central fishing area (19.9 g C m-2 d-l) and off the Anto- fagasta upwelling ecosystem (9.3 g C m-' d-'). The range of GPP agrees well with values reported for Peni (0.05 to ll.? g C m'2 d"). -

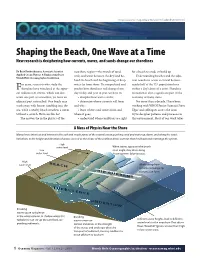

Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New Research Is Deciphering How Currents, Waves, and Sands Change Our Shorelines

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v43n1/raubenheimer.html Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New research is deciphering how currents, waves, and sands change our shorelines By Britt Raubenheimer, Associate Scientist nearshore region—the stretch of sand, for a beach to erode or build up. Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Dept. rock, and water between the dry land be- Understanding beaches and the adja- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hind the beach and the beginning of deep cent nearshore ocean is critical because or years, scientists who study the water far from shore. To comprehend and nearly half of the U.S. population lives Fshoreline have wondered at the appar- predict how shorelines will change from within a day’s drive of a coast. Shoreline ent fickleness of storms, which can dev- day to day and year to year, we have to: recreation is also a significant part of the astate one part of a coastline, yet leave an • decipher how waves evolve; economy of many states. adjacent part untouched. One beach may • determine where currents will form For more than a decade, I have been wash away, with houses tumbling into the and why; working with WHOI Senior Scientist Steve sea, while a nearby beach weathers a storm • learn where sand comes from and Elgar and colleagues across the coun- without a scratch. How can this be? where it goes; try to decipher patterns and processes in The answers lie in the physics of the • understand when conditions are right this environment. Most of our work takes A Mess of Physics Near the Shore Many forces intersect and interact in the surf and swash zones of the coastal ocean, pushing sand and water up, down, and along the coast. -

3. Characterizing the Physical Oceanography of Coastal Waters

Ocean Special Area Management Plan 3. Characterizing the Physical Oceanography of Coastal Waters Off Rhode Island, Part 2: New Observations of Water Properties, Currents, and Waves Prepared for the Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan 2010 By David S. Ullman and Daniel L. Codiga University of Rhode Island, December 21, 2010 December 21, 2010 Technical Report Page 1 of 111 Ocean Special Area Management Plan Executive Summary This report, Part 2 of the physical oceanography characterization, complements Part 1 by presenting new field observations to improve understanding of under-sampled system attributes. Vessel-based surveys spanning the region (Block Island Sound (BIS), Rhode Island Sound (RIS), and offshore) each season capture three-dimensional structure of water properties (temperature, salinity, oxygen, chlorophyll, turbidity) and geographic variations in euphotic depth. Moored instruments reveal temporal variability in water column temperature, salinity, and velocity on timescales from hours to months at four sites: south and southeast of Block Island, on the offshore portion of Cox Ledge at the southern RIS boundary, and in central RIS. A suite of wave parameters measured at those sites, and a fifth site farther offshore, quantifies wave conditions. Temperature and salinity surveys corroborate the main seasonal and geographic patterns deduced in Part 1. Central RIS stratification undergoes the widest seasonal swings: a sharp mid- depth thermocline due to solar insolation in summer, and homogenous conditions in winter due to surface cooling and wind mixing. In central BIS stronger tidal currents limit peak stratification in the summer, but during winter and spring estuarine exchange with Long Island Sound sustains stronger stratification than in RIS. -

Hydrothermal Vent Plume at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-2019-189 Preprint. Discussion started: 20 June 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Successional patterns of (trace) metals and microorganisms in the Rainbow 2 hydrothermal vent plume at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge 3 Sabine Haalboom1,*, David M. Price1,*,#, Furu Mienis1, Judith D.L van Bleijswijk1, Henko C. de 4 Stigter1, Harry J. Witte1, Gert-Jan Reichart1,2, Gerard C.A. Duineveld1 5 1 NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, department of Ocean Systems, and Utrecht University, PO Box 59, 6 1790 AB Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands 7 2 Utrecht University, Faculty of Geosciences, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands 8 * These authors contributed equally to this work 9 # Current address: University of Southampton, Waterfront Campus, European Way, Southampton, UK, 10 SO14 3ZH. 11 [email protected]; [email protected] 12 13 Keywords: Rainbow vent; Epsilonproteobacteria; Hydrothermal vent plume; Deep-sea mining; Rare 14 earth elements; Seafloor massive sulfides 15 16 Abstract 17 Hydrothermal vent fields found at mid-ocean ridges emit hydrothermal fluids which disperse as neutrally 18 buoyant plumes. From these fluids seafloor massive sulfides (SMS) deposits are formed which are being 19 explored as possible new mining sites for (trace) metals and rare earth elements (REE). It has been 20 suggested that during mining activities large amounts of suspended matter will appear in the water column 21 due to excavation processes, and due to discharge of mining waste from the surface vessel. Understanding 22 how natural hydrothermal plumes evolve as they spread away from their source and how they affect their 23 surrounding environment may provide some analogies for the behaviour of the dilute distal part of 24 chemically enriched mining plumes. -

Excess Sediment Th: Transport Along the Sea Floor Or Enhanced Water

GLOBAL BIOGEOCHEMICAL CYCLES, VOL. 22, GB1006, doi:10.1029/2007GB003057, 2008 Click Here for Full Article Excess sediment 230Th: Transport along the sea floor or enhanced water column scavenging? Wallace Broecker1 Received 9 July 2007; revised 27 August 2007; accepted 10 September 2007; published 5 February 2008. 230 [1] The sedimentary inventory of Th is often employed to distinguish between areas which receive excess sediment as the result of along-bottom transport from those which lose sediment as a result of winnowing. This process is referred to as ‘‘focusing.’’ A case is made here that, at least in the western equatorial Pacific, the excess 230Th in on-equator sediment is more likely scavenged from the overlying water column by the rain of organic matter than retransported along the bottom. If so, lateral variations in biological productivity may well contribute to the excess 230Th inventories elsewhere as well. Citation: Broecker, W. (2008), Excess sediment 230Th: Transport along the sea floor or enhanced water column scavenging?, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 22, GB1006, doi:10.1029/2007GB003057. 1. Introduction is that the width of the excess 230Th-bearing zones on the two sides of the equatorial Pacific appears to mimic the [2] When combined with radiocarbon-based accumula- 230 zone of nutrient-rich surface water (see Figure 1). This zone tion rates, measurements of Th allow the accumulation is very broad adjacent to the Americas and extends further rate of this isotope in marine sediments to be calculated. If to the south of the equator than to the north. It progressively the resulting rate exceeds that for the production in the 230 narrows to the west and becomes more nearly centered on overlying water column, then the Th excess is attributed 230 the equator.