Agur, Dissertation Cover Page & Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Premier League 2019

VVS LAXMAN Published 3.4.19 The last ten days have reiterated just how significant a place the Indian Premier League has carved for itself on the cricke�ng landscape. Spectacular ac�on and stunning performances have brought the tournament to life right from the beginning, and I expect the next six weeks to be no less gripping. From our point of view, I am delighted at how well Hyderabad have bounced back from defeat in our opening match, against Kolkata. Even in that game, we were in control �ll the end of the 17th over of the chase, but Andre Russell took it away from us with brilliant ball-striking. Even though I was in the opposi�on dugout, I couldn’t help but marvel at how he snatched victory from the jaws of defeat. The beauty of our franchise is that the shoulders never droop, the heads never drop. There is too much experience, quality and class among the playing group for that to happen. As members of the support staff, our endeavour is to keep the players in a good mental space. But eventually, it is the players who have to deliver on the park, and that’s what they have done in the last two games. David Warner has been outstanding. There is li�le sign that he has been out of interna�onal cricket for a year. His work ethics are exemplary, and I can see the hunger and desire in his eyes. He is striking the ball as beau�fully as ever, and there is a calmness about him that is infec�ous. -

IPL 2014 Schedule

Page: 1/6 IPL 2014 Schedule Mumbai Indians vs Kolkata Knight Riders 1st IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 16, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Delhi Daredevils vs Royal Challengers Bangalore 2nd IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 17, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Chennai Super Kings vs Kings XI Punjab 3rd IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 18, 2014 | 14:30 local | 10:30 GMT Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals 4th IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 18, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Mumbai Indians 5th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 19, 2014 | 14:30 local | 10:30 GMT Kolkata Knight Riders vs Delhi Daredevils 6th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 19, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Rajasthan Royals vs Kings XI Punjab 7th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 20, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Chennai Super Kings vs Delhi Daredevils 8th IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 21, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Kings XI Punjab vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 9th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 22, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Rajasthan Royals vs Chennai Super Kings 10th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 23, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Kolkata Knight Riders Page: 2/6 11th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 24, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Delhi Daredevils 12th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 25, 2014 -

The Annual Report on the Most Valuable and Strongest IPL Brands December 2019 About Brand Finance

IPL 2019 The annual report on the most valuable and strongest IPL brands December 2019 About Brand Finance. Contents. Brand Finance is the world’s leading independent About Brand Finance 2 brand valuation consultancy. Get in Touch 2 Brand Finance was set up in 1996 with the aim of ‘bridging the gap between marketing and finance’. For Request Your Brand Value Report 4 more than 20 years, we have helped companies and organisations of all types to connect their brands to the Brand Valuation Methodology 5 bottom line. Foreword 6 We pride ourselves on four key strengths: Executive Summary 8 + Independence + Transparency + Technical Credibility + Expertise Picture TBD 15 We put thousands of the world’s biggest brands to the Definitions 16 test every year, evaluating which are the strongest and most valuable. Sponsorship Services 18 Brand Finance helped craft the internationally Sports Services 19 recognised standard on Brand Valuation – ISO 10668, and the recently approved standard on Brand Communications Services 20 Evaluation – ISO 20671. Brand Finance Network 22 Get in Touch. For business enquiries, please contact: Savio D'Souza Director [email protected] For media enquiries, please contact: Sehr Sarwar BrandirectoryGlobal Forum 2019 Communications Director [email protected] For all other enquiries, please contact: Understanding the Value of [email protected] Geographic Branding +44 (0)207 389 9400 The world's largest 2 April 2019 brand value database. For more information, please visit our website: www.brandfinance.com Join us at the Brand Finance Global Forum, anVisit action-packed to see all day-long Brand event Finance at the Royal rankings,Automobile Club reports, in London, and as wewhitepapers explore how linkedin.com/company/brand-finance geographic branding can impact brand value, attract customers, and infl uence key stakeholders.published since 2007. -

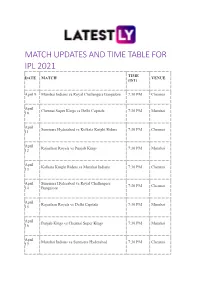

Match Updates and Time Table for Ipl 2021 Time Date Match Venue (Ist)

MATCH UPDATES AND TIME TABLE FOR IPL 2021 TIME DATE MATCH VENUE (IST) April 9 Mumbai Indians vs Royal Challengers Bangalore 7:30 PM Chennai April Chennai Super Kings vs Delhi Capitals 7:30 PM Mumbai 10 April Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Kolkata Knight Riders 7:30 PM Chennai 11 April Rajasthan Royals vs Punjab Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 12 April Kolkata Knight Riders vs Mumbai Indians 7:30 PM Chennai 13 April Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Royal Challengers 7:30 PM Chennai 14 Bangalore April Rajasthan Royals vs Delhi Capitals 7:30 PM Mumbai 15 April Punjab Kings vs Chennai Super Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 16 April Mumbai Indians vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 7:30 PM Chennai 17 April Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Kolkata Knight 3:30 PM Chennai 18 Riders April Delhi Capitals vs Punjab Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 18 April Chennai Super Kings vs Rajasthan Royals 7:30 PM Mumbai 19 April Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians 7:30 PM Chennai 20 April Punjab Kings vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 3:30 PM Chennai 21 April Kolkata Knight Riders vs Chennai Super Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 21 April Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Rajasthan Royals 7:30 PM Mumbai 22 April Punjab Kings vs Mumbai Indians 7:30 PM Chennai 23 April Rajasthan Royals vs Kolkata Knight Riders 7:30 PM Mumbai 24 April Chennai Super Kings vs Royal Challengers 3:30 PM Mumbai 25 Bangalore April Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Delhi Capitals 7:30 PM Chennai 25 April Punjab Kings vs Kolkata Knight Riders 7:30 PM Ahmedabad 26 April Delhi Capitals vs Royal Challengers Bangalore 7:30 PM Ahmedabad 27 April Chennai Super Kings vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 7:30 -

Balance Sheet Merge Satistics & Color Bitmap.Cdr

MADHYA PRADESH CRICKET ASSOCIATION Holkar Stadium, Khel Prashal, Race Course Road, INDORE-452 003 (M.P.) Phone : (0731) 2543602, 2431010, Fax : (0731) 2534653 e-mail : [email protected] Date : 17th Aug. 2011 MEETING NOTICE To, All Members, Madhya Pradesh Cricket Association. The Annual General Body Meeting of Madhya Pradesh Cricket Association will be held at Holkar Stadium, Khel Prashal, Race Course Road, Indore on 3rd September 2011 at 12 Noon to transact the following business. A G E N D A 1. Confirmation of the minutes of the previous Annual General Body Meeting held on 22.08.2010. 2. Adoption of Annual Report for 2010-2011. 3. Consideration and approval of Audited Statement of accounts and audit report for the year 2010-2011. 4. To consider and approve the Proposed Budget for the year 2011-2012. 5. Appointment of the Auditors for 2011-2012. 6. Any other matter with the permission of the Chair. (NARENDRA MENON) Hon. Secretary Note : 1. If you desire to seek any information, you are requested to write to Hon. Secretary latest by 28th Aug. 2011. 2. The Quorum for meeting is One Third of the total membership. If no quorum is formed, the Meeting will be adjourned for 15 minutes. No quorum will be necessary for adjourned meeting. The adjourned meeting will be held at the same place. THE MEETING WILL BE FOLLOWED BY LUNCH. 1 MADHYA PRADESH CRICKET ASSOCIATION, INDORE UNCONFIRMED MINUTES OF ANNUAL GENERAL BODY MEETING HELD ON 22nd AUGUST 2010 A meeting of the General Body of MPCA was held on Sunday 22nd Aug’ 2010 at Usha Raje Cricket Centre at 12.00 noon. -

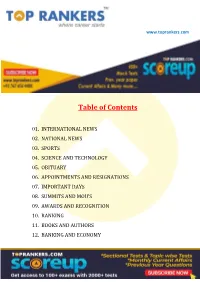

Table of Contents

www.toprankers.com Table of Contents 01. INTERNATIONAL NEWS 02. NATIONAL NEWS 03. SPORTS 04. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 05. OBITUARY 06. APPOINTMENTS AND RESIGNATIONS 07. IMPORTANT DAYS 08. SUMMITS AND MOU’S 09. AWARDS AND RECOGNITION 10. RANKING 11. BOOKS AND AUTHORS 12. BANKING AND ECONOMY www.toprankers.com INTERNATIONAL NEWS India, Netherlands sign agreement to support decarbonisation NITI Aayog of India and the Embassy of the Netherlands in New Delhi have signed a Statement of Intent on September 28, 2020 to support decarbonisation and energy transition agenda in order to accommodate cleaner energy. The main objective of the partnership is to co-create innovative technological solutions. The SoI was signed by NITI Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant and Ambassador of the Netherlands to India Marten van den Berg. India extends $1 bn credit line to Central Asian countries The second meeting of the India-Central Asia Dialogue was held virtually, under the chairmanship of the External Affairs Minister of India Dr S Jaishankar. The foreign minister of all the five Central Asian countries- Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan– participated in the meeting. During the meeting, India announced US $1 billion line of credit for “priority developmental projects” in Central Asian countries in the fields of connectivity, energy, IT, healthcare, education, agriculture and offered to provide grant assistance for implementation of High Impact Community Development Projects (HICDP) for furthering socio-economic development in the countries of the region. Apart from this, the Acting Foreign Minister of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan also attended the meeting as a special invitee. The first India-Central Asia Dialogue was held in Uzbekistan’s Samarkand in 2019. -

Political News Election

HTTP://WWW.UPSCPORTAL.COM POLITICAL NEWS ELECTION COMMISSION AT 60 After overseeing 15 general elections to the Lok Sabha, the Election Commission of India, in its diamond jubilee year, can with justifiable pride claim to have nursed and st rengthened the electoral processes of a nascent democracy. The successes have not been consiste nt or uniform, but over the last six decades the ECI managed to make the worlds largest democratic p rocess freer and fairer. One of the instruments of this success is surely the Model Code of C onduct. D esigned to offer a level playing field to all political parties, it has been used to neu tralise many of the inherent advantages of a ruling party in an election. Although the model code wa s originally based on political consensus and does not still enjoy statutory sanction, it served as a handy tool for placing curbs on the abuse of the official machinery for campaigning. While ther e have been complaints of excess in the sometimes mindless application of the model code, th e benefits have generally outweighed the costs. After the Election Commission was made a three-member body, its functioning beca me more institutionalised and more transparent with little room for the caprices of an o verbearing personality. The diamond jubilee is also an occasion for the ECI to look at the challenges ah ead, especially those relating to criminalisation of politics and use of money power in elections. Neither of these issues is new. What is clear is that the efforts of the Commission to t ackle them have generally lacked conviction and have not yielded any significant results. -

“Felicitation Programme to Best Auto Drivers for the Initiative My Auto Is Safe”

“FELICITATION PROGRAMME TO BEST AUTO DRIVERS FOR THE INITIATIVE MY AUTO IS SAFE” Today, i.e., on 3rd May 2019 Sri Anjani Kumar, IPS., Commissioner of Police, Hyderabad felicitated best Auto drivers who got good feedback from Citizens under the initiative “My Auto Is Safe.” Hyderabad City Police has launched “My Auto Is Safe” programme in the month of January-2019 for the digitalization of all autos plying in the limits of Hyderabad City to curb illegal activities of unsocial elements to make SAFE HYDERABAD and also get a brand image to the Auto Drivers. Under this, till now 35,000 Autos are registered and displaying the QR coded UV printed board in their autos which is visible to the passengers sitting in the rear seat at all times. Passengers who travelled in Autos registered under “My Auto is Safe” given their opinion and feedback on drivers, in which 20 Auto drivers have got 5 Star ratings and 4200 Auto drivers have got 3 Star ratings. Eight Auto drivers who attended this programme also shared their views about this initiative My Auto Is Safe and expressed that with this initiative they are getting good name and response from citizens and their business is running well. Experiences shared by the passengers who got benefited by this initiative: “Ms. Krishnaveni, College Student stated that while travelling from Kukatpally to Secunderabad in an Auto took a photo of the QR Board in front of me and shared to my friend. Unfortunately, I forgot the hall ticket in Auto and got down at my college. -

Reportable in the High Court of Judicature at Bombay

WWW.LIVELAW.IN Board of Control for Cricket in India vs Deccan Chronicle Holding Ltd CARBPL-4466-20-J.docx GP A/W AGK & SSM REPORTABLE IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION IN ITS COMMERCIAL DIVISION COMM ARBITRATION PETITION (L) NO. 4466 OF 2020 Board of Control for Cricket in India, a society registered under the Tamil Nadu Societies Registration Act 1975 and having its head office at Cricket Centre, Wankhede Stadium, Mumbai 400 020 … Petitioner ~ versus ~ Deccan Chronicle Holdings Ltd, a company incorporated under the Companies Act 1956 and having its registered office at 36, Sarojini Devi Road, Secunderabad, Andhra Pradesh … Respondent appearances Mr Tushar Mehta, Solicitor General, with FOR THE PETITIONER Samrat Sen, Kanu Agrawal, Indranil “BCCI” Deshmukh, Adarsh Saxena, Ms R Shah and Kartik Prasad, Advocates i/b Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas Page 1 of 176 16th June 2021 ::: Uploaded on - 16/06/2021 ::: Downloaded on - 16/06/2021 17:38:08 ::: WWW.LIVELAW.IN Board of Control for Cricket in India vs Deccan Chronicle Holding Ltd CARBPL-4466-20-J.docx Mr Haresh Jagtiani, Senior Advocate, with Mr Navroz Seervai, Senior Advocate, FOR THE RESPONDENT Mr Sharan Jagtiani, Senior Advocate, “DCHL” Yashpal Jain, Suprabh Jain, Ankit Pandey, Ms Rishika Harish & Ms Bhumika Chulani, Advocates i/b Yashpal Jain CORAM : GS Patel, J JUDGMENT RESERVED ON : 12th January 2021 JUDGMENT PRONOUNCED ON : 16th June 2021 JUDGMENT: OUTLINE OF CONTENTS This judgment is arranged in the following parts. A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 4 B. THE CHALLENGE IN BRIEF; SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS................................................ 6 C. THE AMBIT OF SECTION 34 ................................................. -

A Case Study on Deccan Chronicle Holdings Limited: a Tragic Story Of

A CaseStudyonDeccanChronicleHoldingsLimited: A TragicStoryofaPublisher SecondEditionofJIDNYASA : ThirstforKnowledge2014 A CaseStudyonDeccanChronicleHoldingsLimited: A TragicStoryofaPublisher WhyFDIinRetail? A StudywithReferencetoSelectStakeholders A CaseStudyonDeccanChronicleHoldingsLimited: A TragicStoryofaPublisher Prof.SwatiKhatkale (AssistantProfessor,SymbiosisSchoolofBankingManagement) Abstract and converted into a daily. In 1976, congress While celebrating its platinum jubilee (75 years of politician and businessman T Chandrashekhar establishment), Deccan Chronicle Holdings Limited Reddy acquired the company. T C Reddy had a (DCHL) faced a gamut of problems. DCHL, one of variety of businesses like bottling plants, aluminum the top English Newspaper Publishing House in foil, hotels etc. His son, Mr. VenkattaramReddy took Southern India, recently ventured into other over as the chairman of the family business at the age businesses like IPL franchise -Deccan Chargers & of 21. He had Diploma in Printing Technology and Life Style Retail-Odyssey . Mismanagement and was well versed with printing & publishing business. unrelated diversification led to default on its non- But he was more known for his extravagant style of convertible debentures. It faced legal action from having expensive cars, fine cigars and keen interest banks & other financial institutions for non- in horserace bidding. His brother, Mr. Vinayak Ravi repayment of debt and misrepresentation of balance Reddy was co chairman of the company. Mr. sheet. Kotak Mahindra Bank even took actual Vankattaram Reddy's wife, Manjula Reddy worked possession of its Hyderabad based Kodapur plant as senior features editor and their daughter Gayatri under SARFASIAct 2002. This case goes into depth Reddy as features editor. Their son T Vijay Reddy to find out the causes of financial distress. It also was the Vice President (finance) of the company. illustrates various options available to bankers & other financial institutions to recover its loan. -

Markets Today Key Overnight Developments Must Know…

15 October 2012 MARKETS TODAY WORLD INDICES & INDIAN ADRs (US$) 12-Oct-12 Domestic equities are seen opening down today amid weak cues from Latest Points % Chg. overseas markets, though Sept inflation data, due at around 1100 IST, will NIKKEI 225 * 8535.7 1.6 0.0 lend more cues to investors. Also, corporate earnings release will keep action HANG SENG * 21099.3 (37.1) (0.2) stock-specific. Resistance is seen at 5692 levels & support is seen at 5649 DOWJONES 13328.9 2.5 0.0 NASDAQ 3044.1 (5.3) (0.2) levels. Result Watch: Axis Bank, Reliance Industries. Data Watch: India WPI SGX NIFTY FUT* 5677.0 (17.0) (0.3) inflation data for Sept. INFY 44.5 (3.7) (7.6) KEY OVERNIGHT DEVELOPMENTS HDFC BANK 37.5 (0.3) (0.7) Wall street ended down Fri, erasing intraday losses, as renewed Eurozone ICICI BANK 39.5 (0.6) (1.4) TATA MOTORS 25.6 (0.2) (0.6) concerns overshadowed strong Oct consumer confidence data. Most Asian WIPRO 8.6 (0.1) (1.0) indices fell today on cautious investor sentiment ahead of an European Union TATA COMM. 9.5 0.0 0.4 summit in Brussels, where Greece will seek to justify more aid and Spain will * At 08:20 a.m. IST on 15-Oct-12 hold out on seeking a bailout. Gold shed 0.7% to close at $1754.50 per ounce. Crude oil shed 0.2% to close at $91.90 per barrel. MUST KNOW…. India's annual inflation rate based on the new Consumer Price Index EQUITY 12-Oct-12 (Combined) eased to a six-month-low of 9.73% in Sept from 10.03% a Latest 1 Day P/E* P/B* SENSEX 18,675.2 0.2 16.0 2.7 month ago. -

Reportable in the High Court of Judicature at Bombay

Board of Control for Cricket in India vs Deccan Chronicle Holding Ltd CARBPL-4466-20-J.docx GP A/W AGK & SSM REPORTABLE IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION IN ITS COMMERCIAL DIVISION COMM ARBITRATION PETITION (L) NO. 4466 OF 2020 Board of Control for Cricket in India, a society registered under the Tamil Nadu Societies Registration Act 1975 and having its head office at Cricket Centre, Wankhede Stadium, Mumbai 400 020 … Petitioner ~ versus ~ Deccan Chronicle Holdings Ltd, a company incorporated under the Companies Act 1956 and having its registered office at 36, Sarojini Devi Road, Secunderabad, Andhra Pradesh … Respondent appearances Mr Tushar Mehta, Solicitor General, with FOR THE PETITIONER Samrat Sen, Kanu Agrawal, Indranil “BCCI” Deshmukh, Adarsh Saxena, Ms R Shah and Kartik Prasad, Advocates i/b Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas Page 1 of 176 16th June 2021 ::: Uploaded on - 16/06/2021 ::: Downloaded on - 16/06/2021 20:04:41 ::: Board of Control for Cricket in India vs Deccan Chronicle Holding Ltd CARBPL-4466-20-J.docx Mr Haresh Jagtiani, Senior Advocate, with Mr Navroz Seervai, Senior Advocate, FOR THE RESPONDENT Mr Sharan Jagtiani, Senior Advocate, “DCHL” Yashpal Jain, Suprabh Jain, Ankit Pandey, Ms Rishika Harish & Ms Bhumika Chulani, Advocates i/b Yashpal Jain CORAM : GS Patel, J JUDGMENT RESERVED ON : 12th January 2021 JUDGMENT PRONOUNCED ON : 16th June 2021 JUDGMENT: OUTLINE OF CONTENTS This judgment is arranged in the following parts. A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 4 B. THE CHALLENGE IN BRIEF; SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS................................................ 6 C. THE AMBIT OF SECTION 34 .................................................. 10 D. THE FRANCHISE AGREEMENT OF 10TH APRIL 2008 .....................................................................