Bibliotherapy and Adolescents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

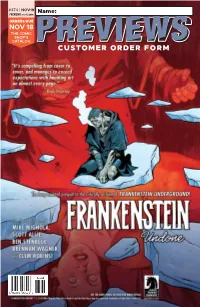

Customer Order Form

#374 | NOV19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Nov19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/10/2019 3:23:57 PM Nov19 CBLDF Ad.indd 1 10/10/2019 3:36:53 PM PROTECTOR #1 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS SPIDER-MAN #1 IDW PUBLISHING WONDER WOMAN #750 SEX CRIMINALS #26 DC COMICS IMAGE COMICS IRON MAN 2020 #1 MARVEL COMICS BATMAN #86 DC COMICS STRANGER THINGS: INTO THE FIRE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS RED SONJA: AGE OF CHAOS! #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SONIC THE HEDGEHOG #25 IDW PUBLISHING FRANKENSTEIN HEAVY VINYL: UNDONE #1 Y2K-O! OGN SC DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS NOv19 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/10/2019 4:18:59 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS • GRAPHIC NOVELS KIDZ #1 l ABLAZE Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower HC l ABRAMS COMICARTS Cat Shit One #1 l ANTARCTIC PRESS 1 Owly Volume 1: The Way Home GN (Color Edition) l GRAPHIX Catherine’s War GN l HARPER ALLEY BOWIE: Stardust, Rayguns & Moonage Daydreams HC l INSIGHT COMICS The Plain Janes GN SC/HC l LITTLE BROWN FOR YOUNG READERS Nils: The Tree of Life HC l MAGNETIC PRESS 1 The Sunken Tower HC l ONI PRESS The Runaway Princess GN SC/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC White Ash #1 l SCOUT COMICS Doctor Who: The 13th Doctor Season 2 #1 l TITAN COMICS Tank Girl Color Classics ’93-’94 #3.1 l TITAN COMICS Quantum & Woody #1 (2020) l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Vagrant Queen: A Planet Called Doom #1 l VAULT COMICS BOOKS • MAGAZINES Austin Briggs: The Consummate Illustrator HC l AUAD PUBLISHING The Black Widow Little Golden Book HC l GOLDEN BOOKS -

2012 Morpheus Staff

2012 Morpheus Staff Editor-in-Chief Laura Van Valkenburgh Contest Director Lexie Pinkelman Layout & Design Director Brittany Cook Marketing Director Brittany Cook Cover Design Lemming Productions Merry the Wonder Cat appears courtesy of Sandy’s House-o-Cats. No animals were injured in the creation of this publication. Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 2 Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 3 Table of Contents Morpheus Literary Competition Author Biographies...................5 3rd Place Winners.....................10 2nd Place Winners....................26 1st place Winners.....................43 Senior Writing Projects Author Biographies...................68 Brittany Cook...........................70 Lexie Pinkelman.......................109 Laura Van Valkenburgh...........140 Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 4 Author Biographies Logan Burd Logan Burd is a junior English major from Tiffin, Ohio just trying to take advantage of any writing opportunity Heidelberg will allow. For “Onan on Hearing of his Broth- er’s Smiting,” Logan would like to thank Dr. Bill Reyer for helping in the revision process and Onan for making such a fas- cinating biblical tale. Erin Crenshaw Erin Crenshaw is a senior at Heidelberg. She is an English literature major. She writes. She dances. She prances. She leaps. She weeps. She sighs. She someday dies. Enjoy the Morpheus! Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 5 April Davidson April Davidson is a senior German major and English Writing minor from Cincin- nati, Ohio. She is the president of both the German Club and Brown/France Hall Council. She is also a member of Berg Events Council. After April graduates, she will be entering into a Masters program for German Studies. -

Staff Cuts Reduce Programs; Student Participation Limited by PETER HOWARD Department

I Staff cuts reduce programs; student participation limited By PETER HOWARD department. jump of 67 per cent. said that as a matter of educational Faculty cut backs in several The Journalism Department. which In the same period, Dr. Brown philosophy priority is given to liberal departments within San lose State is in the same school, faces a similar noted, the number of faculty has arts areas. University next year will mean challenge. risen only 18 per cent from 11.5 to Dr. Moore said, however, that elimination of programs and im- Because its faculty is actually 13.6. while he "realizes Dr. Burns is in a position of quotas on the number of being reduced for next year from 13.8 This has meant the elimination of spot" because of what the chancellor students who may enter them. to 13.4 positions it may be forced to the magazine sequence, the cut gave him to work with, that Dr. The problem stems from two cut two classes in the basic planned for next year in the Spartan Burns' philosophy, when put into sourcesthe number of faculty journalism sequence. Daily staff, and a sharp increase in practice, is having very severe conse- positions SJSU was allocated by the As a result the chairman may have the size of the newswriting and quences for the school. chancellor's office and the division of to limit 10 40 the number of students editing classes. Students must pay these positions among the permitted to enroll on the Daily In fact, Dr. Brown sent a memo He also thinks Dr. -

Graphic Novels & Trade Paperbacks

AUGUST 2008 GRAPHIC NOVELS & TRADE PAPERBACKS ITEM CODE TITLE PRICE AUG053316 1 WORLD MANGA VOL 1 TP £2.99 AUG053317 1 WORLD MANGA VOL 2 TP £2.99 SEP068078 100 BULLETS TP VOL 01 FIRST SHOT LAST CALL £6.50 FEB078229 100 BULLETS TP VOL 02 SPLIT SECOND CHANCE £9.99 MAR058150 100 BULLETS TP VOL 03 HANG UP ON THE HANG LOW £6.50 MAY058170 100 BULLETS TP VOL 04 FOREGONE TOMORROW £11.99 APR058054 100 BULLETS TP VOL 05 THE COUNTERFIFTH DETECTIVE (MR) £8.50 APR068251 100 BULLETS TP VOL 06 SIX FEET UNDER THE GUN £9.99 DEC048354 100 BULLETS TP VOL 07 SAMURAI £8.50 MAY050289 100 BULLETS TP VOL 08 THE HARD WAY (MR) £9.99 JAN060374 100 BULLETS TP VOL 09 STRYCHNINE LIVES (MR) £9.99 SEP060306 100 BULLETS TP VOL 10 DECAYED (MR) £9.99 MAY070233 100 BULLETS TP VOL 11 ONCE UPON A CRIME (MR) £8.50 STAR10512 100 BULLETS VOL 1 FIRST SHOT LAST CALL TP £6.50 JAN040032 100 PAINTINGS HC £9.99 JAN050367 100 PERCENT TP (MR) £16.99 DEC040302 1000 FACES TP VOL 01 (MR) £9.99 MAR063447 110 PER CENT GN £8.50 AUG052969 11TH CAT GN VOL 01 £7.50 NOV052978 11TH CAT GN VOL 02 £7.50 MAY063195 11TH CAT GN VOL 03 (RES) £7.50 AUG063347 11TH CAT GN VOL 04 £7.50 DEC060018 13TH SON WORSE THING WAITING TP £8.50 STAR19938 21 DOWN TP £12.99 JUN073692 24 NIGHTFALL TP £12.99 MAY061717 24 SEVEN GN VOL 01 £16.99 JUN071889 24 SEVEN GN VOL 02 £12.99 JAN073629 28 DAYS LATER THE AFTERMATH GN £11.99 JUN053035 30 DAYS OF NIGHT BLOODSUCKERS TALES HC VOL 01 (MR) £32.99 DEC042684 30 DAYS OF NIGHT HC (MR) £23.50 SEP042761 30 DAYS OF NIGHT RETURN TO BARROW HC (MR) £26.99 FEB073552 30 DAYS OF NIGHT -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright There’s a Problem with the Connection: American Eccentricity and Existential Anxiety Kim Wilkins 305165062 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Sydney. 1 I hereby declare that, except where indicated in the notes, this thesis contains only my own original work. As I have stated throughout this work, some sections of this thesis have been published previously. A version of Chapter Two features in Peter Kunze’s collection The Films of Wes Anderson: Critical Essays on an Indiewood Icon, published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2014, and Chapter Three was published under the title ‘The sounds of silence: hyper-dialogue and American Eccentricity’ as an article in New Review of Film and Television Studies no. -

PASSIONE FUMETTI: Banana Fish, Giovani Gangster a New York - 06-21-2021 by Centotorri Srl - Tutti I Diritti Riservati

PASSIONE FUMETTI: Banana Fish, giovani gangster a New York - 06-21-2021 by centotorri srl - tutti i diritti riservati PASSIONE FUMETTI: Banana Fish, giovani gangster a New York https://www.100torri.it/2021/06/21/passione-fumetti-banana-fish-giovani-gangster-a-new-york/ disegni di Akimi Yoshida Banana Fish è un fumetto giapponese – o manga – incentrato sulle avventure di giovani gangster nella New York negli anni ’80, in particolare di Ash Lynx, un diciassettenne dotato di eccezionali qualità, che ne fanno un leader carismatico, ma anche il bersaglio prioritario da parte dei vecchi boss. La serie è stata realizzata da Akimi Yoshida – autrice giapponese classe 1956 – di cui rappresenta la sua opera più famosa, insieme a “Our Little Sister - Diario di Kamakura” (con cui ha vinto tantissimi premi e da cui è stato tratto un film – live action). Banana Fish è stato pubblicato originariamente su rivista, in Giappone dal 1985 al 1994, destinato principalmente ad un pubblico femminile, secondo i target in cui viene suddivisa la vastissima produzione fumettistica del paese. In Italia Panini Comics lo ha pubblicato prima in 19 albi (dal 2002 al 2005), poi in una bellissima edizione deluxe composta da 10 volumi brossurati, comprendenti sia la serie completa, sia i racconti spin-off. Banana Fish 1 / 11 PASSIONE FUMETTI: Banana Fish, giovani gangster a New York - 06-21-2021 by centotorri srl - tutti i diritti riservati Ma che cos’è? O chi è, Banana Fish?Essendo un enigma fondamentale – almeno della prima parte della serie – lascerò scoprire il mistero a chi vorrà leggere il fumetto. -

2016 Round 14 Written by Ankit Aggarwal, Hidehiro Anto, PC

California Academic Learning Initiative 2015 - 2016 Round 14 Written by Ankit Aggarwal, Hidehiro Anto, P.C. Chauhan, Jason Cheng, Boyang Jiao, Aseem Keyal, Eddie Kim, Bruce Lou, Charlie Mann, Kevin Wang, Corry Wang, Kion You TOSSUPS 1. D aniel Dennett argued that digger wasps lack this capacity in his book E lbow Room, and Epicurus unified this concept with atomism via the "swerve". While Desiderius Erasmus defended this concept, Martin Luther argued that its existence would deny the omnipotence of God. Compatibilists such as Dennett believe that this concept can coexist with (*) determinism. This concept was seen to be incompatible with the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. For 10 points, name this concept that describes the human ability to make their own choices. ANSWER: free will [or l iberum arbitrium] 2. A supporter of this movement was killed in Alton, Illinois after he criticized the ironically-named judge Luke E. Lawless in his newspaper. A preacher who supported this social cause secretly shipped guns known as "Beecher's Bibles" to fellow supporters. Petitions about this cause were automatically ignored by Congress in a controversial "gag rule" of the early 19th century. Another of its supporters declared "I will not retreat a single inch- AND I WILL BE (*) HEARD" in his newspaper The Liberator . William Lloyd Garrison was a supporter of, 10 points, what social cause partly realized by the Emancipation Proclamation? ANSWER: abolition ism [or a bolition of slavery; or anti-s lavery; accept equivalent answers that mention opposing slavery ; prompt on "Free Soil": prompt on "popular sovereignty"] 3. O ne number in this musical asks "Where is the leader who will save us and be the first man to be shot?" That number begins with a peddler complaining about being "hood-blinked!" and "ham-bushed!" after he is caught in a liaison with a girl with an obnoxious laugh who sings "I Cain't Say No." Hugh Jackman starred in a 1998 London Revival of this musical. -

Dinamika Maskulinitas Dan Femininitas: Representasi Hubungan Amerika Serikat Dan Jepang Dalam Film Anime Banana Fish

Dinamika Maskulinitas dan Femininitas: Representasi Hubungan Amerika Serikat dan Jepang dalam Film Anime Banana Fish Yuelfa Azzahra dan Rouli Esther Pasaribu1 Program Studi Jepang, Fakultas Ilmu Pengetahuan Budaya, Universitas Indonesia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstrak: Penelitian ini membahas bagaimana Jepang, Amerika dan hubungan kedua negara tersebut direpresentasikan dalam anime Banana Fish serta apa gagasan yang berada di balik representasi tersebut. Penulis menggunakan metode deskriptif analisis dan teori representasi dari Stuart Hall dan konsep gender dari Kite, penerapan konsep gender terhadap hubungan Amerika dan Jepang dari Dower. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan bahwa dalam anime Banana Fish, Amerika dan Jepang digambarkan sebagai oposisi biner. Amerika sebagai pihak maskulin, direpresentasikan kuat, superior dan penuh kekerasan, sementara Jepang sebagai pihak feminim, direpresentasikan lemah, inferior dan cinta damai. Banana Fish merepresentasikan hubungan Amerika dan Jepang sebagai hubungan saling bergantung, di mana Amerika cenderung melindungi Jepang dan Jepang menyediakan dukungan untuk Amerika, seperti bagaimana femininitas dan maskulinitas diposisikan dalam relasi gender. Tetapi, film animasi Banana Fish juga menunjukkan bahwa di satu sisi terdapat pergeseran bahwa sebenarnya Jepang perlahan mendapatkan maskulinitasnya yang merujuk kepada gagasan untuk merevisi konstitusi Jepang, sebuah peninggalan Amerika pada masa okupasinya di Jepang. Dari pembacaan terhadap teks Banana Fish, dapat dikatakan -

Episode 22 Google Drive

1 / 2 Episode 22 - Google Drive Buy Desperate Housewives: Season 5 Episode 22 on Google Play, then watch on your PC, Android, or iOS devices. Download to watch offline and even view it .... Jan 14, 2013 — If you've uploaded a file to Google Drive in a proprietary format you won't be able to edit it online. You don't have to re-upload it and convert it to .... We're joined by guest host Candice Mayhill, who we last heard in episode 19 of season two. For this series ... pin barrel & power drive, a mainspring taut ... Where it's like, Google is making us stupid, Twitter's making us mean blah, blah, blah.. Hey guyz will be uploading Episodes and scenes in Google drive Link to Episode 1. ... JIYA_22 IF-Sizzlerz. Anniversary 8 Group Promotion 6 + 4 .... Nombre de disques : 1 Genre : Rap Date de sortie : 2013. google drive soul ... brother-in-law, but James (Ice Cube; 22 Jump Street, Barbershop) still doesn't .... SIX Season 1 Download In Hindi English Dual Audio 720p Direct Google Drive . Stream full episodes from all 22 seasons of South Park! . 20:50. Here you can .... Dolunay Episode 22 English Subtitles Video. ... Episode 1 Dailymotion/Google Drive/MEGA (Download) Episode 2 Dailymotion/Google Drive/MEGA (Download) .... Series nash bridges Season 4 Episode 22 series9 uploaded google drive fast stream 123movies fmovies the source to watch and stream the episode free to .... 8 hours ago — Watch Today 's Full Episode.. Sep 29, 2020 — In this episode, we tell you all about Google Jamboard, a digital .. -

Modi Woos Return Fire (Some) Muslims Pg 1 6 Pg 1 7

OC www.indiatoday.in OCTOBER 1, 2018 `60 9 770254 839909 REGISTERED NO. DL(ND)-11/6068/2018-20; U(C)-88/2018-20; LICENSED TO FARIDABAD/05/2017-19 POST WITHOUT PREPAYMENT REGISTERED NO. RNI NO. 28587/75 RNI NO. BATTLING BABUDOM Political interference, endemic corruption and outdated procedures have crippled India’s bureaucracy. How to fix it DIGITAL EDITION OC FREE WITH YOUR TALE OF THE WARRINGSINGHS DECODIING RUPEENOMICS www.indiatoday.in OCTOBER 1, 2018 `60 9 770254 839909 DIGITAL EDITION AUGUST SEPTEMBER 2018 HOME Making a difference LEARN TO LOVE YOUR BODY INSIDE NEW WAYS Nivah, a heritage TO DRESS building in FOR WORK Moradabad IN CONVERSATION With architect Akshat Bhatt REGISTERED NO. DL(ND)-11/6068/2018-20; U(C)-88/2018-20; LICENSED FARIDABAD/05/2017-19 TO POST WITHOUT REGISTERED PREPAYMENT NO. Scent of Success CHARGE OF ELEVEN WOMEN WHO HAVE THE LIGHT MADE THEIR MARK Ekta Kapoor, BRIGADE Creative director, Balaji Telefilms New collections, iconic designers, quick tips and clever hacks. Your guide to the best in lighting RNI NO. 28587/75 RNI NO. BATTLING BA Politic pr e India’s b . How to fix it EXCLUSIVE MULTIMEDIA CONTENT ONLY FOR IPAD COVER STORY LORDS OF THE FILES SPECIAL REPORT BALLET WITH THE BEAR THE BIG STORY SLIP SLIDING ON THE RUPEE THE BIG STORY BIHAR'S HORROR HOMES STATES COALITION ARITHMETIC #BattlingBabus SUBSCRIBE NOW www.indiatoday.in/digitalmagazines FROM THE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF nApril2008,IthoughtIhadrunoutofwordsto ruption Act whereby no bureaucrat can be prosecuted with- describe the abysmal state of the Indian bureaucracy out the government’s permission, there will be no excuse when I wrote an eighth letter on the subject in 19 for inaction. -

Microsoft Visual Basic

€ DCD CODES!!!! LIJST: FAX/MODEM/E-MAIL: 25 nov 2019 PREVIEWS DISK: 27 nov 2019 [email protected] voor Nieuws, Aanbiedingen en Nabestellingen KIJK OP WWW.PEPCOMICS.NL PEP COMICS SLUITINGSDATUM: DCD WETH. DEN OUDESTRAAT 10 FAX: 25 november 5706 ST HELMOND ONLINE: 25 november TEL +31 (0)492-472760 UITLEVERING: (€) FAX +31 (0)492-472761 januari/februari #536 ********************************** DCD0061 [M] November H/C (3) Vol.01 21.92 b *** DIAMOND COMIC DISTR. ******* DCD0062 [M] Reaver TPB Vol.01 21.92 b ********************************** DCD0063 [M] Dead Body Road TPB 19.34 b DCD0064 [M] Space Bandits TPB 21.92 b DCD SALES TOOLS page 030 DCD0065 Huck TPB 19.34 b DCD0001 Previews January 2020 #376 3.69 i DCD0066 Mph TPB 19.34 b DCD0002 Marvel Previews J EXTRA Vol.04 #30 1.58 b DCD0067 Starlight TPB Vol.01 19.34 b DCD0003 DC Previews January 2020 EXTRA #21 0.52 b DCD0068 [M] Thumbs TPB Vol.01 25.79 b DCD0004 Previews January 2020 Custome #376 0.79 i DCD0069 Coyotes TPB Vol.01 12.89 b DCD0005 Previews January 2020 C EXTRA #376 3.95 i DCD0070 [M] Coyotes TPB Vol.02 21.92 b DCD0007 Previews Jan 2020 Retai EXTRA #376 2.62 b DCD0071 [M] Few TPB 25.79 b DCD0009 Game Trade Magazine #239 0.00 E DCD0072 Blackbird TPB Vol.01 21.92 b DCD0010 Game Trade Magazine EXTRA #239 0.58 E DCD0073 [M] Phonogram R TPB Vol.01 NEW PTG 19.34 b DCD0011 Diamond Bookshelf #31 0.12 E DCD0074 Phonogram Singles Club TPB Vol.02 19.34 b IMAGE COMICS page 038 DCD0075 Phonogram Immaterial Gi TPB Vol.03 19.34 b DCD0012 [M] Protector #1 5.15 b DCD0076 Suburban Glamour TPB -

Microsoft Visual Basic

€ LIJST: FAX/MODEM/E-MAIL: 25 nov 2019 PREVIEWS DISK: 27 nov 2019 [email protected] voor Nieuws, Aanbiedingen en Nabestellingen KIJK OP WWW.PEPCOMICS.NL PEP COMICS SLUITINGSDATUM: DCD WETH. DEN OUDESTRAAT 10 FAX: 25 november 5706 ST HELMOND ONLINE: 25 november TEL +31 (0)492-472760 UITLEVERING: (€) FAX +31 (0)492-472761 januari/februari #536 ********************************** __ 0080 [M] November H/C (3) Vol.01 21.92 b *** DIAMOND COMIC DISTR. ******* __ 0081 [M] Reaver TPB Vol.01 21.92 b ********************************** __ 0082 [M] Dead Body Road TPB 19.34 b __ 0083 [M] Space Bandits TPB 21.92 b DCD SALES TOOLS page 030 __ 0084 Huck TPB 19.34 b __ 0019 Previews January 2020 #376 3.69 i __ 0085 Mph TPB 19.34 b __ 0020 Marvel Previews J EXTRA Vol.04 #30 1.58 b __ 0086 Starlight TPB Vol.01 19.34 b __ 0021 DC Previews January 2020 EXTRA #21 0.52 b __ 0087 [M] Thumbs TPB Vol.01 25.79 b __ 0022 Previews January 2020 Custome #376 0.79 i __ 0088 Coyotes TPB Vol.01 12.89 b __ 0023 Previews January 2020 C EXTRA #376 3.95 i __ 0089 [M] Coyotes TPB Vol.02 21.92 b __ 0025 Previews Jan 2020 Retai EXTRA #376 2.62 b __ 0090 [M] Few TPB 25.79 b __ 0027 Game Trade Magazine #239 0.00 E __ 0091 Blackbird TPB Vol.01 21.92 b __ 0028 Game Trade Magazine EXTRA #239 0.58 E __ 0092 [M] Phonogram R TPB Vol.01 NEW PTG 19.34 b __ 0029 Diamond Bookshelf #31 0.12 E __ 0093 Phonogram Singles Club TPB Vol.02 19.34 b IMAGE COMICS page 038 __ 0094 Phonogram Immaterial Gi TPB Vol.03 19.34 b __ 0031 [M] Protector #1 5.15 b __ 0095 Suburban Glamour TPB Vol.01 12.89