Musqueam Comprehensive Land Claim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography of British Columbia1

Bibliography of British Columbia1 Compiled by Eve Szabo, Senior Librarian, Social Sciences Division, W. A. G. Bennett Library, Simon Fraser University. Books ALBERNI DISTRICT MUSEUM AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY. Place names of (he Alberni Valley. Supplement 1982. Port Alberni, B.C., 1982. 15 p. ALLEN, Richard Edward. Heritage Vancouver: a pictorial history of Van couver. Book 2. Winnipeg, Josten's Publications, 1983. 100 p. $22.95. ANDERSON, Charles P. and others, editors. Circle of voices: a history of the religious communities of British Columbia. Lantzville, B.C., Oolichan Books, 1983. 288 p. $9.95. BARRETT, Anthony A. and Rhodri Windsor Liscombe. Francis Rattenbury and British Columbia: architecture and challenge in the imperial age. Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 1983. 391 p. $29.95. BASQUE, Garnet. Methods of placer mining. Langley, B.C., Sunfire Publi cations, 1983. 127 p. $6.95. (This is also History of the Canadian West special issue, November 1983.) BOWMAN, Phylis. "The city of rainbows [Prince Rupert]!" Prince Rupert, B.C., [the author], 1982. 280 p. $9.95. CONEY, Michael. Forest ranger, ahoy!: the men, the ships, the job. Sidney, B.C., Porthole Press, 1983. 232 p. $24.95. ECKEL, Catherine C. and Michael A. Goldberg. Regulation and deregula tion of the brewing industry: the British Columbia example. Working paper, no. 929. Vancouver, University of British Columbia, Faculty of Commerce and Business Administration, 1983. 53 p. GOULD, Ed. Tut, tut, Victoria! Victoria, Cappis Press, 1983. 181 p. $6.95. HARKER, Byron W. Kamloops real estate: the first 100 years. Kamloops, [the author], 1983. 324 p. $40.00. -

HOW to BENEFIT As a Member Or Seasons Pass Holder at One of Vancouver’S Must See Attractions You Are Eligible for Savings and Benefits at Other Top Attractions

HOW TO BENEFIT As a Member or Seasons Pass holder at one of Vancouver’s Must See Attractions you are eligible for savings and benefits at other top Attractions. Simply present your valid membership or pass at participating Attractions’ guest services, retail outlet or when you make a reservation to enjoy a benefit. There is no limit to the number of times you may present your valid membership or seasons pass. Capilano Suspension Bridge Park featuring the iconic Suspension Bridge, Treetops Adventure, 7 suspended footbridges offering views 100 feet above the forest floor and the Cliffwalk, a labyrinth-like series of narrow cantilevered bridges, stairs and platforms high above the Capilano River offers you 20% off Food and Beverage, (excluding alcohol) at any of our Food & Beverage venues within the park excluding the Cliff House Restaurant and Trading Post gift store. 604.985.7474 capbridge.com Step aboard an old-fashioned horse-drawn vehicle for a Stanley Park Horse-Drawn Tour and meander in comfort through the natural beauty of Stanley Park, Vancouver’s thousand acre wonderland. Three great offers available for members: A) Enjoy a 2 for 1 offer ($42 value) for our regularly-scheduled Stanley Park Horse-Drawn Tours; B) $50 off of a Private Carriage Reservation within Stanley Park and the downtown core of Vancouver, or C) $100 off a Private Carriage Reservation taking place outside of Stanley Park and the downtown core of Vancouver. Restrictions: Must be within our regular operating season of March 1 – December 22. Private carriage bookings must be made in advance. 604.681.5115 stanleypark.com Sea otters, sea lions, snakes and sloths…plus 60,000 other aquatic creatures, await your arrival at the Vancouver Aquarium, conveniently located in Stanley Park. -

Programs & Services Summer 2019

Programs & Services Summer 2019 Watch for our FREE “Fun for All” programs! See inside for details. Registration Information Program Registration Refund Policy 1) Register Online at Registration Hours • A full refund will be granted if requested up to 48 hours prior to the britanniacentre.org at Info Centre Mon-Fri 9:00am-6:30pm second class. No refunds after this Registration starts at 9:00am Sat 9:30am-4:00pm time. on Tuesday June 4, 2019 Sun 10:30am-3:00pm • For workshops and outings, a full refund will be granted if the refund is requested one week (seven days) 2) Register in Person Registration Hours prior to the start of the program. No Registration starts at 9:00am at Pool Cashier refunds after this time. • Britannia Society Memberships are on Tuesday June 4, 2019 Mon-Thu 9:00am-9:00pm non-refundable. Sat 9:30am-7:00pm • For day camps, a $5 administration Sun 10:30am-7:00pm fee will be charged for each camp 3) Register by Phone at a refund is requested for. Refund 604.718.5800 ext. 1 You must have a current Britannia requests must be made one week Phone registration starts at 1:00pm membership to register for programs. (seven days) prior to the start of the program. No refunds after this time. on Tuesday June 4, 2019 Swim/Skate Refunds Summer 2019 Subsidy Policy • Full refund will be granted five days or more prior to the start of the program. Holiday Hours Britannia provides assistance to those who • Partial refunds granted within four are not able to afford the advertised cost days of program start or before Information Centre of certain programs and activities. -

T S a Ww As Sen C Ommons

Ferry Terminal SOUTH DELTA Splashdown Waterpark Salish Sea Drive Tsawwassen Mills Highway 17 (SFPR) Tsawwassen Commons Trevor Linden Fitness 52 Street Fisherman Way FOR LEASE 90% LEASED! TSAWWASSEN TSAWWASSEN COMMONS SHELDON SCOTT ARJEN HEED Personal Real Estate Corporation Associate Colliers International Executive Vice President +1 604 662 2685 200 Granville Street | 19th Floor +1 604 662 2660 [email protected] Vancouver, BC | V6C 2R6 [email protected] P: +1 604 681 4111 | collierscanada.com TO LEASE SPACE IN SOUTH DELTA’S BRAND NEW OPPORTUNITY TSAWWASSEN COMMONS SHOPPING CENTRE. Join national tenants such as Walmart, Canadian Tire, and Rona in servicing the affluent market of South Delta; and, the large daytime working populations from the surrounding businesses and industrial park. MUNICIPAL Big Box and Shop Component: SALIENT ADDRESS 4949 Canoe Pass Way, Delta, BC V4M 0B2 Service Commercial (Lot 5): FACTS 4890 Canoe Pass Way, Delta, BC V4M 0B1 LEGAL ADDRESS Big Box and Shop Component: PID: 029-708-702 Lot B Section 15 Township 5 New Westminster District Plan EPP42761 Service Commercial Site (Lot 5): PID: 029-708-745 Lot C Section 15 Township 5 New Westminster District Plan EPP42761 GROSS RENTABLE Currently Developed: 450,000 SF (approximately) AREA Potential Expansion: 70,000 SF (approximately) PARKING 1,798 for a ratio of 4 stalls per 1000 SF of rentable area (as of January 2019) AVAILABILITY Please see Site Plan herein ACCESS/EGRESS Salish Sea Drive: Signalized intersection at Canoe Pass Way Salish Sea Drive: Right -

People, Parks, and Dogs Strategy Report

A strategy for sharing Vancouver's parks 1 PEOPLE, PARKS & DOGS: A STRATEGY FOR SHARING VANCOUVER’S PARKS Prepared for the Vancouver Park Board, October 2017 by space2place design inc. in collaboration with: Kirk & Co Consulting Ltd. PUBLIC Architecture + Communication MountainMath Software Pet Welfare Cover image: Michael Wheatley / Alamy Stock Photo CONTENTS PEOPLE, PARKS + DOGS STRATEGY REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A 10-Year Framework 2 Recommendations Overview 2 INTRODUCTION Purpose of the Strategy 5 Process Overview 6 BACKGROUND What's Working Well (and not) 8 Existing Dog Off-Leash Areas 11 Population and Licensing 11 Service Analysis 12 Analysis of 3-1-1 Calls 13 RECOMMENDATIONS 01 Access 16 02 Design 21 03 Stewardship 33 04 Enforcement 39 Considerations for Other Agencies 43 DELIVERY Quick Starts 45 Renewal of Existing Dog Off-Leash Areas 46 New Dog Off-Leash Areas 47 Pilot Projects 49 Partnership Opportunities 49 Monitoring and Evaluation 51 COMPANION DOCUMENTS Appendix Implementation Guide - Considerations for Delivery Round 1 Consultation Summary Report Round 2 Consultation Summary Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As in many other major A 10-Year Framework North American cities, the number of people The Vancouver Park Board's People, Parks & Dogs Strategy provides a framework and dogs in Vancouver is for the next ten years and beyond, to deliver well-planned and designed parks that accommodate park users with and without dogs and minimize conflict. growing. With population Recommendations fall into four themes: Access, Design, Stewardship -

Self-Guiding Geology Tour of Stanley Park

Page 1 of 30 Self-guiding geology tour of Stanley Park Points of geological interest along the sea-wall between Ferguson Point & Prospect Point, Stanley Park, a distance of approximately 2km. (Terms in bold are defined in the glossary) David L. Cook P.Eng; FGAC. Introduction:- Geomorphologically Stanley Park is a type of hill called a cuesta (Figure 1), one of many in the Fraser Valley which would have formed islands when the sea level was higher e.g. 7000 years ago. The surfaces of the cuestas in the Fraser valley slope up to the north 10° to 15° but approximately 40 Mya (which is the convention for “million years ago” not to be confused with Ma which is the convention for “million years”) were part of a flat, eroded peneplain now raised on its north side because of uplift of the Coast Range due to plate tectonics (Eisbacher 1977) (Figure 2). Cuestas form because they have some feature which resists erosion such as a bastion of resistant rock (e.g. volcanic rock in the case of Stanley Park, Sentinel Hill, Little Mountain at Queen Elizabeth Park, Silverdale Hill and Grant Hill or a bed of conglomerate such as Burnaby Mountain). Figure 1: Stanley Park showing its cuesta form with Burnaby Mountain, also a cuesta, in the background. Page 2 of 30 Figure 2: About 40 million years ago the Coast Mountains began to rise from a flat plain (peneplain). The peneplain is now elevated, although somewhat eroded, to about 900 metres above sea level. The average annual rate of uplift over the 40 million years has therefore been approximately 0.02 mm. -

2014-2015 Annual Report Aboriginal Tourism Association of BC

2014-2015 Annual Report Aboriginal Tourism Association of BC The Next Phase – Year 3 • July 2015 2 2014-2015 AnnUAL REPOrt Aboriginal Tourism Association of BC 3 Table of Contents About the Aboriginal Tourism Association of British Columbia 4 Chair’s Message 6 CEO’s Message 7 Key Performance Indicators 8 2014 / 15 Financials: The Next Phase –Year 3, Statement of Operations Budget vs. Actual 9 Departmental Overviews Klahowya Village in Stanley Park, Vancouver BC Training & Product Development 10 Marketing 14 Authenticity Programs 22 Aboriginal Travel Services 24 Partnerships and Outreach Activities 27 Gateway Strategy 31 Appendix A: Stakeholder - Push for Market-Readiness 35 Appendix B: Identify & Support Tourism Opportunities 43 The Aboriginal Tourism Association of BC acknowledges the funding contribution from Destination BC, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development and Western Economic Diversification Canada. 4 2014-2015 AnnUAL REPOrt Aboriginal Tourism Association of BC 5 About the Aboriginal Tourism Association Goals Strategic Priorities of British Columbia • Improve awareness of Aboriginal tourism among Aboriginal Our key five-year strategic priorities are: communities and entrepreneurs • Push for Market-Readiness The Aboriginal Tourism Association of British Columbia (AtBC) is a non-profit, Stakeholder-based organization • Support tourism-based development, human resources and • Build and Strengthen Partnerships economic growth and stability in Aboriginal communities that is committed to growing and promoting a sustainable, culturally rich Aboriginal tourism industry. • Focus on Online Marketing • Capitalize on key opportunities, such as festivals and events Through training and development, information resources, networking opportunities and co-operative that will forward the development of Aboriginal cultural • Focus on Key and Emerging marketing programs, AtBC is a one-stop resource for Aboriginal entrepreneurs and communities in British tourism Markets Columbia who are operating or looking to start a tourism business. -

New Product Guide Spring Edition 2019

New Product Guide Spring Edition 2019 Harbour Air | Whistler Air Hotel Belmont Landsea Tours and Adventures ACCOMMODATION TRANSPORTATION AND SIGHTSEEING HOTEL BELMONT HARBOUR AIR | WHISTLER AIR Opening May 2019, with 82 fully renovated rooms, guests will Now offering daily seasonal flights (May - September) from South embrace being in the heart of Downtown Vancouver and pay Terminal YVR to Whistler. This new route allows easy access for homage to its historic lights and legendary nights. This boutique YVR passengers to transfer directly to a mid-day scheduled flight hotel is set to attract a mindset more than an age demographic, to Whistler. Complimentary shuttle service is available between offering superior guest service and attention to detail while Main and South Terminals. This convenient new route will appeal driving culturally inspired, fun, and insider experiences to the to both those arriving or departing YVR, as well as those travellers Granville Street Entertainment District. hotelbelmont.ca staying outside of the downtown Vancouver core. harbourair.com LANDIS HOTEL & SUITES LANDSEA TOURS AND ADVENTURES The recently completed $2 million renovation includes convenient Launching on May 1, the Hop On, Hop Off City Tour operates on features designed for comfort and ease. A suites-only hotel in modern double-decker buses, with the upper levels featuring a the heart of Vancouver’s downtown core, the accommodations glass skylight to allow for natural light and spectacular views of are spacious and condo-inspired, each featuring stunning views, the city. Tickets are purchased for a specific tour date year-round, a fully-equipped kitchen, two generous bedrooms and separate with pickups every 30-40 minutes on a 2-hour & 15-minute tour living and dining spaces. -

Downloaded from the Online Library of the International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ISSMGE)

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR SOIL MECHANICS AND GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING This paper was downloaded from the Online Library of the International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ISSMGE). The library is available here: https://www.issmge.org/publications/online-library This is an open-access database that archives thousands of papers published under the Auspices of the ISSMGE and maintained by the Innovation and Development Committee of ISSMGE. The paper was published in the proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Landslides and was edited by Miguel Angel Cabrera, Luis Felipe Prada-Sarmiento and Juan Montero. The conference was originally scheduled to be held in Cartagena, Colombia in June 2020, but due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, it was held online from February 22nd to February 26th 2021. SCG-XIII INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON LANDSLIDES. CARTAGENA, COLOMBIA- JUNE 15th-19th-2020 Methods comparison to predict debris avalanche and debris flow susceptibility in the Capilano Watershed, British Columbia, Canada Silvana Castillo* and Matthias Jakob^ *Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of British Columbia ^BGC Engineering Inc. [email protected] Abstract Landslide susceptibility can be assessed by statistical and empirical methods. Statistical methods often require landslide conditioning factors and inventories of events to predict the occurrence probability for regional scales. In contrast, empirical methods compute susceptibility values based on theorical concepts and compare them with observations. Both approaches were followed to evaluate debris avalanche and debris flow susceptibility in the Capilano Watershed in southwestern B.C. This was accomplished through Random Forest (RF) and Flow-R models. The RF model resulted in predictive accuracies of 76% and 83% for debris avalanche and debris flow models, respectively, and 45% and 28% of the total watershed area were classified as high susceptibility for these landslide types, respectively. -

Hop-On Hop-Off

HOP-ON Save on Save on TOURS & Tour Attractions SIGHTSEEING HOP-OFF Bundles Packages Bundle #1 Explore the North Shore Hop-On in Vancouver + • Capilano Suspension Bridge Tour Whistler • Grouse Mountain General Admission* • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass This bundle takes Sea-to-Sky literally! Start by taking in the spectacular ocean You Save views in Vancouver before winding along Adult $137 $30 the Sea-to-Sky Highway and ascending into Child $61 $15 the coastal mountains. 1 DAY #1: 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass 2020 WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 APR 30, Your perfect VanDAY #2: Whistler + Shannon Falls Tour* Sea to Bridge Experience You Save • Capilano Suspension Bridge day on Hop-On, Adult $169 $30 • Vancouver Aquarium Child $89 $15 • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass You Save Hop-Off Operates: Dec 1, 2019 - Apr 30, 2020 Classic Pass Adult $118 $30 The classic pass is valid for 48 hours and * Whistler + Shannon Falls Tour operates: Child $53 $15 Choose from 26 stops at world-class • Dec 1, 2019 - Jan 6, 2020, Daily includes both Park and City Routes • Apr 1 - 30, 2020, Daily attractions and landmarks at your • Jan 8 - Mar 29, 2020, Wed, Fri, Sat & Sun 2 own pace with our Hop-On, Hop-Off Hop-On, Hop-Off + WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 - APR 30, 2020 WINTER 19 - OCT 1, 2019 APR 30, Sightseeing routes. $49 $25 Lookout Tower Special Adult Child (3-12) Bundle #2 Hop-On in Vancouver + • Vancouver Lookout Highlights Tour Victoria • 48H Hop-On, Hop-Off Classic Pass • 26 stops, including 6 stops in Stanley Park CITY Route PARK Route and 1 stop at Granville Island Take an in-depth look at Vancouver at You Save (Blue line) (Green Line) your own pace before journeying to the Adult $53 $15 • Recorded commentary in English, French, Spanish, includes 9 stops includes 17 stops quaint island city of Victoria on a full day of Child $27 $8 German, Japanese, Korean & Mandarin Fully featuring: featuring: exploration. -

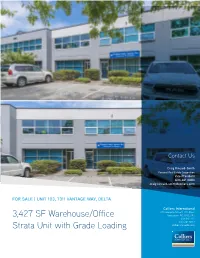

3,427 SF Warehouse/Office Strata Unit with Grade Loading

Contact Us Craig Kincaid-Smith Personal Real Estate Corporation Vice President 604 661 0883 [email protected] FOR SALE | UNIT 103, 7311 VANTAGE WAY, DELTA Colliers International 200 Granville Street | 19th Floor 3,427 SF Warehouse/Office Vancouver, BC | V6C 2R6 604 681 4111 604 661 0849 Strata Unit with Grade Loading collierscanada.com FOR SALE > OFFICE/WAREHOUSE UNIT IN TILBURY Unit 103 - 7311 Vantage Way, Delta Opportunity & Location Opportunity to purchase a 2,756 SF warehouse/office unit with 671 SF Hi-Cube mezzanine in a prime industrial facility. The subject property is situated on Vantage Way in the popular Tilbury Industrial Area of north Delta. This area is a well known and sought after location for its proximity to major traffic arteries, the Vancouver International Airport, U.S. border and Downtown Vancouver. Access to the major transportation routes such as Highway 17, Highway 99 and Highway 91 are just minutes away and provide excellent links to almost all regions of the Lower Mainland and Metro Vancouver. Available Area* Upstairs Office 874 SF Downstairs Office 492 SF Warehouse 1,390 SF Hi-Cube Mezzanine 671 SF Total 3,427 SF * Measurements are approximate and to be verified by the Purchaser Buntzen Lake Capilano Lake Property Features West r m D r d h R A g u o n > Quality tilt-up construction Vancouver o n r a a r l i i o D p d b s a mar Rd n th n Ave e I u e C ra 99 Upper So v B te Edgemont Blvd S Queens Ave Le ve > 18’ ceilingls height in warehouseDelbrook BC RAIL Mathers Ave d Pitt Lake Highway R E 29th -

A Hundred Years of Natural History the Vancouver Natural History Society, 1918–2018

A Hundred Years of Natural History The Vancouver Natural History Society, 1918–2018 Susan Fisher and Daphne Solecki A Hundred Years of Natural History The Vancouver Natural History Society 1918–2018 A Hundred Years of Natural History: The Vancouver Natural History Society, 1918–2018 © 2018 Vancouver Natural History Society Published by: Vancouver Natural History Society Nature Vancouver PO Box 3021, Stn. Terminal Vancouver, BC V6B 3X5 Printed by: Infigo www.infigo.ca Hundred Years Editorial Committee: Daphne Solecki, Susan Fisher, Bev Ramey, Cynthia Crampton, Marian Coope Book design: Laura Fauth Front cover: VNHS campers on Savary Island, 1918. Photo by John Davidson. City of Vancouver Archives CVA 660-297 Back cover: 2018 Camp at McGillivray Pass. Photos by Jorma Neuvonen (top) and Nigel Peck (bottom). ISBN 978-0-9693816-2-4 To the countless volunteers who have served and continue to serve our society and nature in so many ways. Table of Contents Acknowledgements.......................................... 5 Preface........................................................ 6 The.Past.of.Natural.History............................... 8 John.Davidson.............................................. 13 Indigenous.Connections.................................. 16 Objective.1:.To.promote.the.enjoyment.of.nature... 21 Objective.2:.To.foster.public.interest.and.education. in.the.appreciation.and.study.of.nature..............35 Objective.3:.To.encourage.the.wise.use.and. conservation.of.natural.resources.and Objective.4:.To.work.for.the.complete.protection.