Revolutionary and Nationalistic Spirit in the Select Poems of Wb Yeats And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal Criterion: an International Journal in English ISSN: 0976-8165

About Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/about/ Archive: http://www.the-criterion.com/archive/ Contact Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/contact/ Editorial Board: http://www.the-criterion.com/editorial-board/ Submission: http://www.the-criterion.com/submission/ FAQ: http://www.the-criterion.com/fa/ ISSN 2278-9529 Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal www.galaxyimrj.com www.the-criterion.comThe Criterion: An International Journal in English ISSN: 0976-8165 Mahjoor as a Harbinger of New Age in Kashmiri Poetry: A Study Furrukh Faizan Mir Research Scholar, Department of English University of Kashmir. Hazratbal, Srinagar, Kashmir. The present paper is an attempt to place Mahjoor in the history of Kashmiri poetry and study his outpourings against the form and thematic backgroundprevailing before him,so as to underscore his contributions as aharbinger of a sort of renaissance in twentieth century Kashmiri poetry This paper will also illustration how Mahjoor puffed in a fresh air in Kashmiri poetry while maintaining a middle ground between being an extreme traditional on the one hand,and an outright rebel on the other. Endeavour will also be made to explore how Mahjoor by introducing unprecedented themes and issues like nature, flora and fauna, ordinary day-day aspects, mundane love, local environment, freedom from political, economic and social subjugation etc. not only brought in modernity and a new era in Kashmiri poetrybut also by doing so, expanded its canvas. What is more, unlike earlier poets all these themes were rendered in a language understood alike by the learned and the hoi polloiearning him such titles as “The Poet of Kashmir,” as well as “The Wordsworth of Kashmir”. -

Calander 2021 New.Cdr

2021 CALENDAR CREATING MAGIC FROM THE HILLS MAN WITH A VISION & I N N O VAT I O N THAT LED TO PERFECTION About the Hero of Our Lives ! About PrintForest Mr. Masood Ahmad Bodha , Director PrintForest Kashmir is a well known businessman PrintForest is a HaroonPress Enterprise and business innovator of Doru Shahabad. He was a Professional Photographer and started working with the expertise of more than his career as lone photographer in this area. He burned mid-night oil for his dream with two decades. Providing high quality utmost dedication and self belief. He started his work in 1975 with a business name “Prince printing services around the country. Photo Services” which was famous and was largely acclaimed photo studio in those times. Working with the Prestigous companies He came up with an innovation of Printing Technology time and again. He introduced many of India. A brand that has gained the state of the art printing technologies which is in itself a revolution in Printing Services. attention and is delivering the services In the Year 1992 he came with the vision of providing services to different areas of Kashmir. in and out. He left no stone unturned for the future generations tp get benefited from what he had been BinShahin Tech Services is a subsidiary doing from the last three decades. He expanded his business in the year 2002 with the name of Haroon Press Pvt. Ltd. engaged in Web “Haroon Press”. A business concern for quality printing services across the valley. From last 18 Development and Digital Marketing. -

Book in Pdf Format

PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com WAVES BY ARJAN DEV MAJBOOR ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF KASHMIRI POEMS BY ARVIND GIGOO DRAWINGS BY VIJAY ZUTSHI DEDICATED TO DINA NATH NADIM Published by Kashmir Bhawan CK-35 (Near CK Market) Karunamoyee Salt Lake Calcutta 700 091 West Bengal PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 OTHER BOOKS BY ARJAN DEV MAJBOOR..................................................................3 2.0 CRITICAL REVIEW............................................................................................................4 3.0 TRANSLATOR'S NOTE.......................................................................................................7 4.0 FOREWORD.........................................................................................................................8 5.0 PORTRAIT OF A CHILD...................................................................................................13 6.0 THE BRONZE HAND.........................................................................................................14 7.0 THE TOPSY - TURVY TREE............................................................................................16 8.0 SNOWMAN.........................................................................................................................19 9.0 -

Dina Nath Kaul 'Nadim' the ‘Gentle Colossus’ of Modern Kashmiri Literature Onkar Kachru HIMALAYAN and CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES Editor : K

ISSN 0971-9318 HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES (JOURNAL OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH AND CULTURAL FOUNDATION) NGO in Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC, United Nations Vol. 8 No.1 January - March 2004 NADIM SPECIAL Deodar in a Storm: Nadim and the Pantheon Braj B. Kachru Lyricism in Nadim’s Poetry T.N. Dhar ‘Kundan’ Nadim – The Path Finder to Kashmiri Poesy and Poetics P.N. Kachru D.N. Kaul ‘Nadim’ in Historical Perspective M.L. Raina Dina Nath Kaul 'Nadim' The ‘Gentle Colossus’ of Modern Kashmiri Literature Onkar Kachru HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES Editor : K. WARIKOO Guest Editor : RAVINDER KAUL Assistant Editor : SHARAD K. SONI © Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation, New Delhi. * All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without first seeking the written permission of the publisher or due acknowledgement. * The views expressed in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or policies of the Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation. SUBSCRIPTION IN INDIA Single Copy (Individual) : Rs. 100.00 Annual (Individual) : Rs. 400.00 Institutions : Rs. 500.00 & Libraries (Annual) OVERSEAS (AIRMAIL) Single Copy : US $ 5.00 UK £ 7.00 Annual (Individual) : US $ 30.00 UK £ 20.00 Institutions : US $ 50.00 & Libraries (Annual) UK £ 35.00 The publication of this journal (Vol.8, No.1, 2004) has been financially supported by the Indian Council of Historical Research. The responsibility for the facts stated or opinions expressed is entirely of the authors and not of the ICHR. -

4 M.A English (CBCS).Pdf

POSTGRADUATE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF KASHMIR SRINAGAR 190 006 DEFINITIONS 1 Semester: This will mean one half of an academic year: March to July; and August to December. 2 Programme: This term will be used to designate what at present is usually called a course of study. Thus a normal four-semester (2-year) MA Course in English will henceforth be called M A Programme in English. 3 Course: This word will be used exclusively for a course unit, in a subject or what is at present called ‘paper’. Thus each semester will have a number of courses (core as well as optional). 4 Credit: This is a measure of course/courses successfully completed by a student. A course taught through 5-6 hours a week will have 4 credits. A semester will have 4 courses and each course 4 credits. The quality of a student will be measured by marks. Each course will have 100 marks: 80 for the examination at the end of the course and 20 for continuous assessment. 5 Semester Examination: This will mean the examination held at the end of a semester. 6 Continuous Assessment: Besides the semester examination, the performance of a student will be judged in tutorials, seminars, projects and class tests. A student failing in the continuous assessment will not be allowed to sit in the examination. The record of continuous DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH, KASHMIR UNIVERSITY assessment in each course will be maintained by individual teachers and the master register will be maintained by the office under the supervision of the Head of Department. -

Ghulam Ahmad Mahjoor - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Ghulam Ahmad Mahjoor - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Ghulam Ahmad Mahjoor(3 September 1885 - 9 April 1952) Peerzada Ghulam Ahmad (Kashmiri: ?????? ???? (Devanagari), ???? ???? (Nastaleeq)), better known by the pen name Mahjoor (Kashmiri: ????? (Devanagari), ????? (Nastaleeq)), was a renowned poet of the Indian Kashmir Valley, along with contemporaries, Zinda Kaul, Abdul Ahad Azad, Dinanath Nadim. He is especially noted for introducing a new style into Kashmiri poetry and for expanding Kashmiri poetry into previously unexplored thematic realms. In addition to his poems in Kashmiri, Mahjoor is also noted for his poetic compositions in Persian and Urdu. <b>Early Life</b> Mahjoor was in the village of Metragam, Pulawama, which is located approximately 37 km from the city of Srinagar. Mahjoor followed in the academic footsteps of his father, who was a scholar of Persian language. He received the primary education from the Maktab of Aashiq Trali (a renowned poet) in Tral. After passing the middle school examination from Nusrat-ul-Islam School, Srinagar, he went to Punjab where he came in contact with Urdu poets like Bismil Amritsari and Moulana Shibi Nomani. He returned to Srinagar in 1908 and started writing in Persian and then in Urdu. Determined to write in his native language, Mahjoor used the simple diction of traditional folk storytellers in his writing. Mahjoor worked as a patwari (regional administrator) in Kashmir. Along with his official duties, he spent his free time writing poetry, and his first Kashmiri poem 'Vanta hay vesy' was published in 1918. <b>Poetic Legacy</b> Many of the themes of the poetry of Mahjoor involved freedom and progress in Kashmir, and his poems awakened latent nationalism among Kashmiris. -

L-G-0002443472-0013822608.Pdf

Islam, Women, and Violence in Kashmir Comparative Feminist Studies Series Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Series Editor Published by Palgrave Macmillan: Sexuality, Obscenity, Community: Women, Muslims, and the Hindu Public in Colonial India by Charu Gupta Twenty-First-Century Feminist Classrooms: Pedagogies of Identity and Difference edited by Amie A. Macdonald and Susan Sánchez-Casal Reading across Borders: Storytelling and Knowledges of Resistance by Shari Stone-Mediatore Made in India: Decolonizations, Queer Sexualities, Trans/national Projects by Suparna Bhaskaran Dialogue and Difference: Feminisms Challenge Globalization edited by Marguerite Waller and Sylvia Marcos Engendering Human Rights: Cultural and Socio-Economic Realities in Africa edited by Obioma Nnaemeka and Joy Ezeilo Women’s Sexualities and Masculinities in a Globalizing Asia edited by Saskia E. Wieringa, Evelyn Blackwood, and Abha Bhaiya Gender, Race, and Nationalism in Contemporary Black Politics by Nikol G. Alexander-Floyd Gender, Identity, and Imperialism: Women Development Workers in Pakistan by Nancy Cook Transnational Feminism in Film and Media edited by Katarzyna Marciniak, Anikó Imre, and Áine O’Healy Gendered Citizenships: Transnational Perspectives on Knowledge Production, Political Activism, and Culture edited by Kia Lilly Caldwell, Kathleen Coll, Tracy Fisher, Renya K. Ramirez, and Lok Siu Visions of Struggle in Women’s Filmmaking in the Mediterranean edited by Flavia Laviosa; Foreword by Laura Mulvey Islam, Women, and Violence in Kashmir: Between India and Pakistan by Nyla Ali Khan Islam, Women, and Violence in Kashmir Between India and Pakistan Nyla Ali Khan ISLAM, WOMEN, AND VIOLENCE IN KASHMIR Copyright © Nyla Ali Khan, 2010. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2010 978-0-230-10764-9 All rights reserved. -

Selected Writings of Prof. Braj B. Kachru

PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com SELECTED WRITINGS OF PROF. BRAJ B. KACHRU Copyright © 2007 by Kashmir News Network (KNN) (http://iKashmir.net) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of Kashmir News Network. For permission regarding publication, send an e-mail to [email protected] PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 ABOUT THE AUTHOR........................................................................................................1 2.0 PROFESSOR BRAJ B. KACHRU........................................................................................2 3.0 NAMING IN THE KASHMIRI PANDIT COMMUNITY...................................................4 4.0 KAESHIR KA:NGIR...........................................................................................................15 5.0 KASHMIRI SAMA:VA:R...................................................................................................18 6.0 GRANNY LALLA...............................................................................................................20 7.0 GHULAM AHMAD MAHJOOR........................................................................................22 -

Classical Music of Kashmir As a Cultural Heritage of Kashmir: an Analytical Study Research Scholar: Iqbal Hussain Mir Deptt

© 2020 JETIR January 2020, Volume 7, Issue 1 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Classical Music of Kashmir as a Cultural Heritage of Kashmir: An Analytical Study Research Scholar: Iqbal Hussain Mir Deptt. Of Music, Punjabi University Patiala, Pin: 147002. Abstract The Classical music of Kashmir (Sufiana Mousiqui) is an important component of the Kashmiri society and culture. It is a type of mystical music practiced traditionally by professional musicians belonging to different Gharanas of Kashmir. This musical form has been fashioned over the centuries of its development by a synthesis of foreign as well as indigenous elements. It is a type of composed choral music in which five to twelve musicians led by a leader, sing together to the accompaniment of Santoor, Saaz-i-Kashmir, Kashmiri Sehtar and Dokara/Tabla. Instead of raga, Persian Maqams are used. The text of the songs is mystical Sufi poems in Persian and Kashmiri. This musical genre took shape in the 15th century at the time of Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin (1420-1470). Key words:- Sufiana Mousiqui, Origin, Structure, Singing style, performance. Introduction The region of Kashmir is renowned worldwide for its rich and distinct cultural heritage. Fine arts in general and music in particular form an important component of Kashmir’s glorious cultural heritage. The music of the valley is rich and diverse and consists of three major genres: Folk music of Kashmir, Modern light music of Kashmir and Classical music of Kashmir. Historical background of Classical Music of Kashmir However the origin of Classical music of Kashmir (Sufiana Mousiqui) can be directly attributed to the advent of Islam and the establishment of ‘Saltanat’ period in Kashmir in the fourteenth century, when “Lhachan Gualbu Rinchana” (Rinchan) adopted Islam in 1320 and assumed the title of “Sultan Sadr-Ud-Din”. -

Theses & Dissertations

Research Degrees Awarded The Centre of Central Asian Studies has produced a substantial number of scholars (135 M.Phil. and 89 PhDs). The details are as under: A) Ph. D. Awarded No. Title of Thesis Scholar Supervisor Year 1. The Political Philosophy of Mir Rifat Ara Prof. S. Maqbool 1982 Sayyid Ali Hamdani 2. Sociological Study of Kargil G. M. Dar Prof. S. Maqbool 1982 3. Pakaeigraoguc Study of the Bower Purnima Dr. B. K. Deambi 1983 Manuscripts Kaboo 4. Role of Bihaqi Sayyids of Central Saif-ud-Din Dr. G. M. 1984 Asia (14th Century) Baihaqi Margoob 5. Edition, Translation and Critical Raja Bano Prof. S. Maqbool 1984 Evaluation of the History of Kashmir by Haider Malik 6. A Study of Economic History of Abdul Ahad Prof. A. Wahid & 1985 Ladakh, 1838-1925 Prof. A.M. Mattoo 7. Central Asian (Tajik &Uzbek) Zubaida Jan Dr K. N. Pandita 1986 Society During Timurid Period as Depicted in Medieval Sources 8. Anglo-Soviet Rivalry in Afghanistan, Satish Prof.S.Maqbool 1986 1919-1945 Kumar Ahmad 9. The J&K State & Central Asia: Veena Saraf Dr. Salim Kidwai 1986 Political Relations, 1857-1947 10. Ancient India and Sinkiang – Utpal Koul Dr. B. K. Deambi 1986 Historical, Cultural & Commercial Contacts: 300 B.C. – 500A. D. 11. Influence of Tajik Language on Dilshada Dr. G. M. 1986 Kashmiri Language Shamsi Margoob 12. Indo Afghan Relations: A Politico- A. Hamid Dr. K. N. Pandita 1987 Economic Study (1919-1945) Mir & Dr. Saleem Kidwai 13. Kashmir’s Contribution to Buddhism Advaita Dr. B.K . Deambi 1987 in Central Asia Vadini Koul 14. -

Saraswat Brahmins of Kashmir

Aryan Saraswat Brahmins Of Kashmeere {Kashmir} Through Two Millenniums Of Triumph, Search Of Identity, Conversion Trauma’s, Exodus’s To Pandit Bhawani { 18th/ 19th Century } Contents Part I : Curiosity For Past - Aryan Saraswat Brahmin Honorific Gotra - Genesis, Orientation, Proliferation – Dattatreya’ Gotra Part II : Advent Of Islam By Preachers And Helped By Then Rulers- T yranny - First Exodus 15th Century Part III : Saraswat Bhatta’s And Surnames Part IV : Surname Roots From Shakta Worship - Re- return And Rebirth Gratus Shriya Bhatta {Shri Bhat } - Conversions and Re-Exodus - Stars Rise Under Moghuls : Pandit Honorific Part V : Controversy Pandit Honorific – Under Later Moghuls Afghan’s And Later Dogra Rule ; Star Pandit’s : Narain And Bhawani PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Aryan Saraswat Brahmins Of Kashmeere {Kashmir} Through Two Millenniums Of Triumph, Search Of Identity, Conversion Trauma’s, Exodus’s To Pandit Bhawani { 18th/ 19th Century } - Brigadier Rattan Kaul {The article intends to remind our Gen X of triumphs, traumas, achievements, exoduses and survival of Aryan Saraswat Brahmins of Kashmeere {Kashmir} during the past two millenniums. The inspirational effort goes to Puja, who enters the portals of family of Bhawani Kaul of Kashmeere’s, becomes part of the community and welcomed to philosophy and fold of Aryan Saraswat Brahmins of Kashmeere {Kashmir}, like Queen Yasomati {300 BC} and Queen Ahala {13th Century- who built Ahalamatha Math, present-day ‘Gund Ahlamar’, close to the roots of Bhawani’s descendants }- Author} Part I – Curiosity For Past - Aryan Saraswat Brahmin Honorific - Gotra Genesis, Orientation, Proliferation - Dattatreya Gotra Curiosity For Past. These are not the triumphs and travails of a particular Aryan Saraswat Brahmin of Kashmeere {Kashmir}, commonly referred now as Kashmiri {Kashmeeri} Pandit, but transition of a community through two millenniums of religious philosophies, search of identity, Gotra orientation, honorific’s Bhatta and Pandit and selective surnames. -

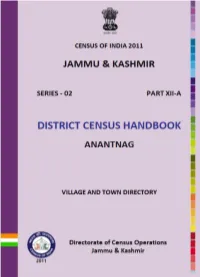

Anantnag a R I G (Notional) Il D

T G A C N D I E R JAMMU & KASHMIR R B A L T DISTR ICT S K DISTRICT ANANTNAG A R I G (NOTIONAL) IL D D S I R S I N T R A R G I C A T R PAHALGAM A A Population..................................1078692 No. of Sub-Districts................... 6 M No of Statutory Towns.............. 12 No of Census Towns................. 0 A W No of Villages............................ 342 W PAHALGAM L ! R Ñ U T P T C H I R T S I S Salar D Forest Block T ! o Sr ! ina ga r BIJBEHARA I D ! AISHMUQUAM Marhama ! ! ! Khiram Sir Hama I ! Waghama NH S 1 ARWANI A ! K 145 Ñ ! 146 ! T ! 147 BIJBEHARA 148 J149 Salia Ponchal Pora Jabli Pora SEER HAMDAN ! Ñ !Nanilang R R MATTAN I N ! J D I A I Ranbir Pora ! SHANGUS ! Chhatar Gul C ANANTNAG ! J Laram ANANTNAG T Jangi P Ñ Pora T ! ACHHABAL SHANGUS Uttarsoo! Brenti Bat Pora Ñ ! K ! ! ! Nowgam R Kothar U ! Fateh Pora C L ! Akin Gam G ! Hillar Arhama Soaf Shalli QAZI GUND I A Sagam ! KOKERNAG ! Ñ ! M Naroo Pora ! Deval Gam ! KOKERNAG R D Ñ ! ! DORU VERINAGRJ J R Dandi Pora I Nala Sund Brari ! ! S T T mu Jam To R I DOORU S C T I BOUNDARY, DISTRICT............................................ R ,, TAHSIL................................................ HEADQUARTERS, DISTRICT................................... P A R M ,, TAHSIL....................................... D Salar VILLAGE HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION ! B WITH NAME............................................................... ! A !! A URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE:-I,III,IV, V ! D NH 1A N O NATIONAL HIGHWAY...............................................