The Winds of Winter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luisa and the Most Precious Blood of Jesus in the Divine Will

Luisa and the Most Precious Blood of Jesus in the Divine Will From the Writings of Luisa Piccarreta Little Daughter of the Divine Will V1 – I go about looking in the middle of the street – but what do I see? I see the street all filled with people, and, in the middle, my Loving Jesus with the Cross upon His Shoulders. Some pulled Him to one side, some to another. All panting, with His Face dripping with Blood, He raised His Eyes toward me in act of asking for my help. V1 – “My Heart was taken by such grips, that I felt It as if It were under a press; so much so, that I sweat Living Blood. Tell Me, when have you arrived at Suffering so much? Therefore, when you find Yourself without Me, afflicted, empty of any Consolation, filled with sadnesses, with worries, with pains, come close to Me, wipe that Blood from Me, offer those Pains to Me as relief for My Most Bitter Agony. By doing so, you shall find the way to be able to remain with Me after Communion.” V1 – “Daughter, see how My Son is treated by men – the horrible offenses they commit, that never give Him respite. Look at Him, how He Suffers.” And I tried to look at Him, and I saw Him all Blood, all Wounds, and almost cut up, reduced to a mortal state.” V1 – As I lost consciousness, Our Lord made Himself seen once again with the Crown of Thorns on His Head, all dripping with Blood; and turning to me, He said: “Daughter, take a look at what men do to Me. -

Mhysa Or Monster: Masculinization, Mimicry, and the White Savior in a Song of Ice and Fire

Mhysa or Monster: Masculinization, Mimicry, and the White Savior in A Song of Ice and Fire by Rachel Hartnett A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL August 2016 Copyright 2016 by Rachel Hartnett ii Acknowledgements Foremost, I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude to my advisor Dr. Elizabeth Swanstrom for her motivation, support, and knowledge. Besides encouraging me to pursue graduate school, she has been a pillar of support both intellectually and emotionally throughout all of my studies. I could never fully express my appreciation, but I owe her my eternal gratitude and couldn’t have asked for a better advisor and mentor. I also would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Dr. Eric Berlatsky and Dr. Carol McGuirk, for their inspiration, insightful comments, and willingness to edit my work. I also thank all of my fellow English graduate students at FAU, but in particular: Jenn Murray and Advitiya Sachdev, for the motivating discussions, the all-nighters before paper deadlines, and all the fun we have had in these few years. I’m also sincerely grateful for my long-time personal friends, Courtney McArthur and Phyllis Klarmann, who put up with my rants, listened to sections of my thesis over and over again, and helped me survive through the entire process. Their emotional support and mental care helped me stay focused on my graduate study despite numerous setbacks. Last but not the least, I would like to express my heart-felt gratitude to my sisters, Kelly and Jamie, and my mother. -

Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones

Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Gloria Makjanić Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones Završni rad Zadar, 2018. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Preddiplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti (dvopredmetni) Archetypes in Female Characters of Game of Thrones Završni rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Gloria Makjanić dr. sc. Zlatko Bukač Zadar, 2018. Makjanić 1 Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Gloria Makjanić, ovime izjavljujem da je moj završni rad pod naslovom Female Archetypes of Game of Thrones rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga rada. Zadar, 13. rujna 2018. Makjanić 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 2. Game of Thrones ............................................................................................................. 4 3. Archetypes ...................................................................................................................... -

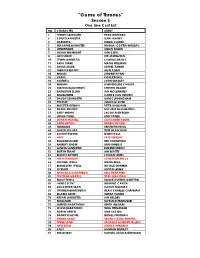

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

Racialization, Femininity, Motherhood and the Iron Throne

THESIS RACIALIZATION, FEMININITY, MOTHERHOOD AND THE IRON THRONE GAME OF THRONES AS A HIGH FANTASY REJECTION OF WOMEN OF COLOR Submitted by Aaunterria Treil Bollinger-Deters Department of Ethnic Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2018 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Ray Black Joon Kim Hye Seung Chung Copyright by Aaunterria Bollinger 2018 All Rights Reserved. ABSTRACT RACIALIZATION, FEMININITY, MOTHERHOOD AND THE IRON THRONE GAME OF THRONES A HIGH FANTASY REJECTION OF WOMEN OF COLOR This analysis dissects the historic preconceptions by which American television has erased and evaded race and racialized gender, sexuality and class distinctions within high fantasy fiction by dissociation, systemic neglect and negating artistic responsibility, much like American social reality. This investigation of high fantasy creative fiction alongside its historically inherited framework of hierarchal violent oppressions sets a tone through racialized caste, fetishized gender and sexuality. With the cult classic television series, Game of Thrones (2011-2019) as example, portrayals of white and nonwhite racial patterns as they define womanhood and motherhood are dichotomized through a new visual culture critical lens called the Colonizers Template. This methodological evaluation is addressed through a three-pronged specified study of influential areas: the creators of Game of Thrones as high fantasy creative contributors, the context of Game of Thrones -

Download 1St Season of Game of Thrones Free Game of Thrones, Season 1

download 1st season of game of thrones free Game of Thrones, Season 1. Game of Thrones is an American fantasy drama television series created for HBO by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss. It is an adaptation of A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin's series of fantasy novels, the first of which is titled A Game of Thrones. The series, set on the fictional continents of Westeros and Essos at the end of a decade-long summer, interweaves several plot lines. The first follows the members of several noble houses in a civil war for the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms; the second covers the rising threat of the impending winter and the mythical creatures of the North; the third chronicles the attempts of the exiled last scion of the realm's deposed dynasty to reclaim the throne. Through its morally ambiguous characters, the series explores the issues of social hierarchy, religion, loyalty, corruption, sexuality, civil war, crime, and punishment. The PlayOn Blog. Record All 8 Seasons Game of Thrones | List of Game of Thrones Episodes And Running Times. Here at PlayOn, we thought. wouldn't it be great if we made it easy for you to download the Game of Thrones series to your iPad, tablet, or computer so you can do a whole lot of binge watching? With the PlayOn Cloud streaming DVR app on your phone or tablet and the Game of Thrones Recording Credits Pack , you'll be able to do just that, AND you can do it offline. That's right, offline . -

Queen of Dragons Free

FREE QUEEN OF DRAGONS PDF Shana Abe | 322 pages | 25 Nov 2008 | Random House USA Inc | 9780553588064 | English | New York, United States Daenerys Targaryen | Game of Thrones Wiki | Fandom Daenerys Targaryen is a fictional character in George Queen of Dragons. In the novels, she is a prominent point of view character. She is one of the most popular characters in the series, and The New York Times cites her as one of the author's finest creations. Introduced in 's A Game of ThronesDaenerys is one of the last surviving members along with her older brother, Viserys of House Targaryenwho, until fourteen years before the events of the first novel, had ruled Westeros from the Iron Queen of Dragons for nearly three hundred years prior to being ousted. Daenerys was one of a few prominent characters not included in 's A Feast for Crowsbut returned in the next novel A Dance with Dragons In the story, Daenerys is a woman in her early teens living in Essos. Knowing no other life than one of exile, she remains dependent Queen of Dragons her abusive older brother, Viserys. She is forced to marry Dothraki horselord Khal Drogo in exchange for an army for Viserys, who wishes to return to Westeros and recapture the Iron Throne. Her brother loses the ability to control her as Daenerys finds herself adapting to life with the khalasar. Her character emerges as strong, confident and courageous. She Queen of Dragons the heir of the Targaryen dynasty after her brother's Queen of Dragons and plans to reclaim the Iron Throne herself, seeing it as her birthright. -

Cheat Sheet to Westeros and Beyond, Your Guide on Catching up to “Game of Thrones” Before Season 8 Starts April 14

“Game of Thrones” has several great battle scenes, and the sixth season features the Battle of the Bastards, one of the most epic battle scenes ever filmed, movie or television. COURTESY/HBO ith the final season of “Game of Thrones” fast approaching, you might feel a little left out of the pop culture phenomenon as ‘GAME OF your friends and family discuss Targaryens, Starks and Lan- nisters. But it’s not too late to get caught up, if you’re willing to Wtake a crash course in the Seven Realms. THRONES’ Today we’re giving you a cheat sheet to Westeros and beyond, your guide on catching up to “Game of Thrones” before Season 8 starts April 14. This is by no means complete. We definitely recommend you take time later to go back and watch the entire series, which is epic in scale and qual- TV ity. We’ve boiled the show’s 67 episodes down to 28, or a little over 26 hours ‘Game of CHEAT Thrones’ season of viewing. While you won’t get every detail, this list will give you what you 8 premiere need to understand the major plot points. With a bit of dedication, you can 8 p.m. April 14, HBO get through it all in a week. SHEET And if you’re already familiar with Game of Thrones, you can use this as a guide to re-familiarize yourself with the world you’ve been missing for the last 18 months. Your guide to catching up on the Seven Tip: Wikipedia has pretty good summaries for each episode. -

A Game of Thrones Lcg: Tourney for the Hand Chapter Pack Free

FREE A GAME OF THRONES LCG: TOURNEY FOR THE HAND CHAPTER PACK PDF Ffg | none | 19 Oct 2011 | Fantasy Flight Games | 9781616611736 | English | United States Hand's tourney - A Wiki of Ice and Fire Why is that? Well, I believe it comes down to two cards in particular: Tyrion and the Moneylender. So, since events cost gold, you have to carry gold into the Challenges or later phases to make good use of something like Die by the Sword, which costs two gold and lets you choose and kill a character controlled by the losing opponent if you have won a Military challenge by five or more strength. This is where Tyrion Lannister enters the picture. Limit twice per round. Many players consider Tyrion to be the best character in the entire game for this reason. So, since Tyrion is arguably the best character in the game, it begins to make sense why someone would run Banner of the Lion. In a deck like Targaryen Fealty, one of the main benefits of the Fealty agenda is that you can kneel your House card to reduce the cost of a loyal event like Dracarys! Which, if you spend a gold and kneel a Stormborn or a Dragon, lets you choose a participating character to become minus four strength and for them to be killed if their strength is zero. Since Dracarys! However, if you splash in Tyrion, he gives you the benefits of the Banner access to Lannister cards, no limit on neutral cardswithout taking away the ease-of-use events. -

2021 Rittenhouse Game of Thrones Iron Anniversary Series 1

2021 Game of Thrones Iron Ann. S1 Inscription Variations Beckett.com/News Aimee Richardson as Myrcella Baratheon Avoid Dragons PR: 25-50 Game of Thrones PR: 25-50 Hear Me Roar PR: 100-150 House Baratheon PR: 25-50 House Baratheon (or Lannister?) PR: 25-50 I'm a princess! PR: 25-50 Joffrey's Sister PR: 25-50 Myrcella Baratheon PR: 100-150 Ours is the Fury PR: 50-75 Princess for Hire PR: 50-75 Princess Myrcella PR: 50-75 Secretly a Lannister! PR: 25-50 Tommen's sister PR: 25-50 Alfie Allen as Theon Greyjoy Any last words? PR: 50-75 Do the Right Thing PR: 25-50 Game of Thrones PR: 50-75 HOUSE GREYJOY PR: 25-50 I chose wrong PR: 10-25 I did terrible things PR: 25-50 IRONBORN PR: 25-50 It can always be worse PR: 10-25 Pay the iron price! PR: 10-25 REEK PR: 25-50 Theon Greyjoy PR: 50-75 There is no escape PR: 10-25 Amrita Acharia as Irri Doreah Betrayed Me PR: 25-50 dothraki rule PR: 25-50 dothraki Translator PR: 25-50 Game of Thrones PR: 10-25 handmaiden PR: 50-75 I serve Khaleesi PR: 10-25 Irri PR: 100-150 it is known PR: 50-75 She is a Khaleesi PR: 25-50 The Great Stallion PR: 25-50 Ania Bukstein as Kinvara Game of Thrones PR: 25-50 High Pristess PR: 10-25 Kinvara (cursive) PR: 50-75 Kinvara (print) PR: 150-200 1 2021 Game of Thrones Iron Ann. -

Final Draft Thesis Corrected

REDEFINING MASCULINITY IN GAME OF THRONES !1 Redefining Masculinity through Disability in HBO’s Game of Thrones A Capstone Thesis Submitted to Southern Utah University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Communication April 2016 By Amanda J. Dearman Capstone Committee: Dr. Kevin A. Stein, Ph.D., Chair Dr. Arthur Challis, Ed.D. Dr. Matthew H. Barton, Ph.D. Running head: REDEFINING MASCULINITY IN GAME OF THRONES !3 Acknowledgements I have been blessed with the support of a number of number of people, all of whom I wish to extend my gratitude. The completion of my Master’s degree is an important milestone in my academic career, and I could not have finished this process without the encouragement and faith of those I looked toward for support. Dr. Kevin Stein, I can’t thank you enough for your commitment as not only my thesis chair, but as a professor and colleague who inspired many of my creative endeavors. Under your guidance I discovered my love for popular culture studies and, as a result, my voice in critical scholarship. Dr. Art Challis and Dr. Matthew Barton, thank you both for lending your insight and time to my committee. I greatly appreciate your guidance in both the completion of my Master’s degree and the start of my future academic career. Your support has been invaluable. Thank you. To my family and friends, thank you for your endless love and encouragement. Whether it was reading my drafts or listening to me endlessly ramble on about my theories, your dedication and participation in this accomplishment is equal to that of my own. -

Master Dialogue from Seasons 1 and 2

Master Dialogue Document for Dothraki—David J. Peterson 1 Master Dialogue Document for Dothraki All scripts and all postproduction work from all seasons will be entered into this document. Note: The audio files in this section can be found in the "Dialogue" folder inside the • • • "Audio Files" folder. Notes 7/12 Script: For the first round, we received the version of the script that was accurate on 7/12/2008. The scenes from there have since changed, but I've left the translations in for the purposes of comparison. Requested Translation: Finalists were given a series of notes to follow in preparing their final proposals. Among these notes were requests that specific phrases be translated (these phrases themselves appear later in the script, anyway, but I translated them separately just in case that's the way they were wanted). They'll come first. Master Dialogue Document for Dothraki—David J. Peterson 2 GoT SEASON 1 Master Dialogue Document for Dothraki—David J. Peterson 3 Legend Section Title: Scene Description rt1.mp3 Introductory comments, or extra scene/transition/setting information. Dothraki (with stress marked). [phonetic transcription of the standard version] /interlinear gloss/ "English translation." Notes: Extra information (explanations, etymologies, subtleties, metaphors, etc.). Master Dialogue Document for Dothraki—David J. Peterson 4 Requested Translation: From ILLYRIO to DROGO (1) Athchomár chomakaán! rt2.mp3 [aT.tSo.»mar tSo.ma.ka.»an] /respect-NOM. respectful-AGT.-ALL.SG./ "Welcome!" Notes: The phrase here translates to, "Respect to the respectful!" When it comes to outsiders, respect is key for the Dothraki: If outsiders respect them and their culture, they won't kill them.