10. a Comparative Study of Yogangās in Hatha-Yoga And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yoga Makaranda Yoga Saram Sri T. Krishnamacharya

Yoga Makaranda or Yoga Saram (The Essence of Yoga) First Part Sri T. Krishnamacharya Mysore Samasthan Acharya (Written in Kannada) Tamil Translation by Sri C.M.V. Krishnamacharya (with the assistance of Sri S. Ranganathadesikacharya) Kannada Edition 1934 Madurai C.M.V. Press Tamil Edition 1938 Translators’ Note This is a translation of the Tamil Edition of Sri T. Krishnamacharya’s Yoga Makaranda. Every attempt has been made to correctly render the content and style of the original. Any errors detected should be attributed to the translators. A few formatting changes have been made in order to facilitate the ease of reading. A list of asanas and a partial glossary of terms left untranslated has been included at the end. We would like to thank our teacher Sri T. K. V. Desikachar who has had an inestimable influence upon our study of yoga. We are especially grateful to Roopa Hari and T.M. Mukundan for their assistance in the translation, their careful editing, and valuable suggestions. We would like to thank Saravanakumar (of ECOTONE) for his work reproducing and restoring the original pictures. Several other people contributed to this project and we are grateful for their efforts. There are no words sufficient to describe the greatness of Sri T. Krishna- macharya. We began this endeavour in order to better understand his teachings and feel blessed to have had this opportunity to study his words. We hope that whoever happens upon this book can find the same inspiration that we have drawn from it. Lakshmi Ranganathan Nandini Ranganathan October 15, 2006 iii Contents Preface and Bibliography vii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Why should Yogabhyasa be done . -

Issn: 2321-676X Detailing Asanas in Hathayoga Pradipi

Original Article Sunil / Star International Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3(1), March (2018) ISSN: 2321-676X Available online at www.starresearchjournal.com (Star International Journal) STAR YOGA Research Journal UGC Journal No: 63023 DETAILING ASANAS IN HATHAYOGA PRADIPIKA AND GHERANDA SAMHITA- A COMPARITIVE STUDY SUNIL ALPHONSE Assistant Professor of Physical Education, Government College of Engineering, Kannur, Kerala, India. Abstract The purpose of this study is to compare Asanas or postures in two famous authentic traditional yoga texts Hathayoga pradipika and Gheranda samhitha. Asana has been derived from the root ‘as’ which means to sit. Generally the word ‘asana’ using in two contest, the body position which we adopt to sit and the object used for sitting. Most of the Traditional Yogic texts agree regarding the number of important asanas and given 84 asanas. In both Hathayoga pradipika and Gheranda samhitha asanas have been described in detail. For this the researcher studied thoroughly the available commentaries of both texts given by different commentators. There are similarities in most of the Asanas given in both these texts. In Hathayoga Pradipika 15 Asanas has been described in detail whereas in Gheranda samhitha 32 Asanas has been described. Regarding the most important asanas both texts have given the same names. The order in which asanas are arranged is also different in these traditional texts. Regarding the benefits of doing asanas, there are clear aphorisms which describes the benefits in detail. In this modern world there are hundred styles and schools of yoga which have emerged after nineteenth century due to its relevance and high demand by the people towords yoga.The researcher suggests that, It is better to stick to the traditional asanas which have been described in authentic traditional texts like Hathayoga pradipika and Gheranda samhitha instead of running behind so called brand new yoga. -

Pranayama Redefined/ Breathing Less to Live More

Pranayama Redefined: Breathing Less to Live More by Robin Rothenberg, C-IAYT Illustrations by Roy DeLeon ©Essential Yoga Therapy - 2017 ©Essential Yoga Therapy - 2017 REMEMBERING OUR ROOTS “When Prana moves, chitta moves. When prana is without movement, chitta is without movement. By this steadiness of prana, the yogi attains steadiness and should thus restrain the vayu (air).” Hatha Yoga Pradipika Swami Muktabodhananda Chapter 2, Verse 2, pg. 150 “As long as the vayu (air and prana) remains in the body, that is called life. Death is when it leaves the body. Therefore, retain vayu.” Hatha Yoga Pradipika Swami Muktabodhananda Chapter 2, Verse 3, pg. 153 ©Essential Yoga Therapy - 2017 “Pranayama is usually considered to be the practice of controlled inhalation and exhalation combined with retention. However, technically speaking, it is only retention. Inhalation/exhalation are methods of inducing retention. Retention is most important because is allows a longer period for assimilation of prana, just as it allows more time for the exchange of gases in the cells, i.e. oxygen and carbon dioxide.” Hatha Yoga Pradipika Swami Muktabodhananda Chapter 2, Verse 2, pg. 151 ©Essential Yoga Therapy - 2017 Yoga Breathing in the Modern Era • Focus tends to be on lengthening the inhale/exhale • Exhale to induce relaxation (PSNS activation) • Inhale to increase energy (SNS) • Big ujjayi - audible • Nose breathing is emphasized at least with inhale. Some traditions teach mouth breathing on exhale. • Focus on muscular action of chest, ribs, diaphragm, intercostals and abdominal muscles all used actively on inhale and exhale to create the ‘yoga breath.’ • Retention after inhale and exhale used cautiously and to amplify the effect of inhale and exhale • Emphasis with pranayama is on slowing the rate however no discussion on lowering volume. -

History Name What Has Become Known As "Kundalini Yoga" in The

History Name What has become known as "Kundalini yoga" in the 20th century, after a technical term peculiar to this tradition, has otherwise been known[clarification needed] as laya yoga (?? ???), from the Sanskrit term laya "dissolution, extinction". T he Sanskrit adjective ku??alin means "circular, annular". It does occur as a nou n for "a snake" (in the sense "coiled", as in "forming ringlets") in the 12th-ce ntury Rajatarangini chronicle (I.2). Ku??a, a noun with the meaning "bowl, water -pot" is found as the name of a Naga in Mahabharata 1.4828. The feminine ku??ali has the meaning of "ring, bracelet, coil (of a rope)" in Classical Sanskrit, an d is used as the name of a "serpent-like" Shakti in Tantrism as early as c. the 11th century, in the Saradatilaka.[3] This concept is adopted as ku??alnii as a technical term into Hatha yoga in the 15th century and becomes widely used in th e Yoga Upanishads by the 16th century. Hatha yoga The Yoga-Kundalini Upanishad is listed in the Muktika canon of 108 Upanishads. S ince this canon was fixed in the year 1656, it is known that the Yoga-Kundalini Upanishad was compiled in the first half of the 17th century at the latest. The Upanishad more likely dates to the 16th century, as do other Sanskrit texts whic h treat kundalini as a technical term in tantric yoga, such as the ?a?-cakra-nir upana and the Paduka-pañcaka. These latter texts were translated in 1919 by John W oodroffe as The Serpent Power: The Secrets of Tantric and Shaktic Yoga In this b ook, he was the first to identify "Kundalini yoga" as a particular form of Tantr ik Yoga, also known as Laya Yoga. -

Introduction to Yoga

Introduction to Yoga Retreat Handbook 2018 www.PureFlow.Yoga | [email protected] The Guest House This being human is a guest house. Every morning a new arrival. A joy, a depression, a meanness, some momentary awareness comes as an unexpected visitor. Welcome and entertain them all! Even if they are a crowd of sorrows, who violently sweep your house empty of its furniture, still, treat each guest honorably. He may be clearing you out for some new delight. The dark thought, the shame, the malice. meet them at the door laughing and invite them in. Be grateful for whatever comes. because each has been sent as a guide from beyond. - Rumi www.PureFlow.Yoga | [email protected] Contents Part 1: Intro to Yoga Philosophy I. What is Yoga? II. The Practices of Yoga III. Many Paths, One Destination IV. The 8 Limbs of Yoga: Ashtanga Yoga Part 2: The Practices: I. Yamas & Niyamas: Disciplines and Ethics for Freedom II. Asana: a. Sun Salutations b. Alignment Principles c. Developing a Home Practice III. Pranayama IV. Meditation V. Bhakti: Mantra & Kirtan VI. Mudra VII. Sadhana Practice Guide Part 3: Energy Anatomy: I. The Gunas: Sattva, Rajas, & Tamas II. The 5 Koshas III. The 7 Chakras IV. Living Holistically & in Balance Part 4: Ayurveda: Wisdom of Life and Longevity I. Panchabhuta: The 5 Elements II. Ayurvedic Food combining III. Doshas: Elemental constitutions/ Quiz Part 5: Playbook I. Mandala Meditation II. Intention / Sankalpa VIII. Gratitude IX. Reflection & Integration X. Notes & Inspirations XI. Recommended Reading, Viewing & Listening XII. Sangha Love “Do your practice and all is coming”. -

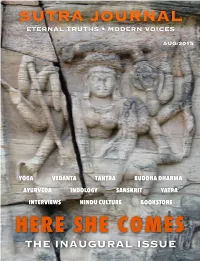

The Inaugural Issue Sutra Journal • Aug/2015 • Issue 1

SUTRA JOURNAL ETERNAL TRUTHS • MODERN VOICES AUG/2015 YOGA VEDANTA TANTRA BUDDHA DHARMA AYURVEDA INDOLOGY SANSKRIT YATRA INTERVIEWS HINDU CULTURE BOOKSTORE HERE SHE COMES THE INAUGURAL ISSUE SUTRA JOURNAL • AUG/2015 • ISSUE 1 Invocation 2 Editorial 3 What is Dharma? Pankaj Seth 9 Fritjof Capra and the Dharmic worldview Aravindan Neelakandan 15 Vedanta is self study Chris Almond 32 Yoga and four aims of life Pankaj Seth 37 The Gita and me Phil Goldberg 41 Interview: Anneke Lucas - Liberation Prison Yoga 45 Mantra: Sthaneshwar Timalsina 56 Yatra: India and the sacred • multimedia presentation 67 If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him Vikram Zutshi 69 Buddha: Nibbana Sutta 78 Who is a Hindu? Jeffery D. Long 79 An introduction to the Yoga Vasistha Mary Hicks 90 Sankalpa Molly Birkholm 97 Developing a continuity of practice Virochana Khalsa 101 In appreciation of the Gita Jeffery D. Long 109 The role of devotion in yoga Bill Francis Barry 113 Road to Dharma Brandon Fulbrook 120 Ayurveda: The list of foremost things 125 Critics corner: Yoga as the colonized subject Sri Louise 129 Meditation: When the thunderbolt strikes Kathleen Reynolds 137 Devata: What is deity worship? 141 Ganesha 143 1 All rights reserved INVOCATION O LIGHT, ILLUMINATE ME RG VEDA Tree shrine at Vijaynagar EDITORIAL Welcome to the inaugural issue of Sutra Journal, a free, monthly online magazine with a Dharmic focus, fea- turing articles on Yoga, Vedanta, Tantra, Buddhism, Ayurveda, and Indology. Yoga arose and exists within the Dharma, which is a set of timeless teachings, holistic in nature, covering the gamut from the worldly to the metaphysical, from science to art to ritual, incorporating Vedanta, Tantra, Bud- dhism, Ayurveda, and other dimensions of what has been brought forward by the Indian civilization. -

Gheranda Samhita the Shiva Samhita

The Gheranda Samhita and the Shiva Samhita 78 YOGAMAGAZINE.COM YOGAMAGAZINE.COM 79 ALL MAGAZINE NOV 17.indd 78 17/10/2017 13:38 PHILOSOPHY Gheranda Samhita (GS) means Gheranda’s compendium and Shiva Samhita (SS) is Shiva’s compendium. These two texts are two of the classic texts of Hatha Yoga (the other one being the Hatha Yoga Pradipika). Lets start with the GS which is a late 17th century text and a manual of yogic practice taught by Gheranda to a student called Chanda Kapali. It has seven chapters, each one taking the practitioner deeper into the experience of yoga. The GS follows this sevenfold division of chapters by creating a seven-limbed yoga, a saptanga yoga. THESE SEVEN LIMBS ARE: Shatkarma - the actions for purification. Asana - for clarity and strength. Mudra - energy seals to focus mind and body energy flow and create appropriate attitudes for practice. Pratyahara - to withdraw the mind from external engagement with the sense fields so you can go inward. Pranayama - working with breath and breath retention to understand and expand life energy flow. This creates lightness and energetic clarity. Dhyana - these are the steps beyond dualistic mind process through Guru yoga and practices of Raja yoga. Samadhi - rests identity as a lived experience, beyond dualistic perceptual patterns, as the totality, Brahman. If you read the articles on Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras you can see the similarities and distinctions. You can find the cross over with the Hatha Yoga Pradipika in the use of mudras and working with Raja yoga. This is a classic Hatha yoga text that starts from the physical experience and works with purification of body first, follows with energetic clarity and concludes with deep interiorisation to know the divine. -

PG Yoga MD(AYU)

CENTRAL COUNCIL OF INDIAN MEDICINE MD (AYURVEDA) FINAL YEAR 17. MD (YOGA) * Teaching hours for theory shall be 100 hours per paper. ** Teaching hours for practical shall be 200 hours. PAPER I PHILOSOPHY OF YOGA MARKS 100 1. Introduction to Yoga concepts from Veda, Upanishads, Puranas and Smruti Samhitas. 2. Concept of Sharira-sthula, Suksma, Karana 3. Shad-Darshanas, relation between Yoga and Sankhya 4. Detailed study of Patanjala yoga Sutras; a. Samadhi Pada( Discourse on Enlightenment) b. Sadhana Pada (Discourse about the Practice) c. Vibhuti Pada ( Discourse about the Results) d. Kaivalya Pada ( discourse about Liberation) 5. Principles of Yoga as per Bhagvad Gita Principles of karma Yoga,( Chapter 3- Path of action and selfless service- karma) & Chapter 5—Path of renunciation in Shrikrishnaconciousness), Jnanayanavijnyana Yoga (Chapter 4 – Jnana karmasanyasa yoga- path of renunciation with self knowledge and Chapter 7—Jnayanvijyan Yoga – enlightenment through knowledge of the Absolute) , Bhakti Yoga (Chapter 12—Path of Devotion). Gunatrayavibhaga Yoga- The three modes-gunas of material nature (chapter 14), Purushottama Yoga- The Yoga of Absolute Supreme Being- (Purushottama) ( chapter 15), Daivasurasamapad vibhaga Yoga- divine and demonic qualities (chapter -16 ) Shraddha Traya Vibhaga Yoga- Three fold faith-( chapter 17) 6. Concepts and Principles of Yoga according to Yoga Vashishtha. CCIM MD Ayurved – Yoga Syllabus Page 1 of 6 PAPER II PRACTICE OF YOGA MARKS 100 (BASED ON HATHA PRADIPIKA, GHERANDA SAMHITA, SHIVA SAMHITA) 1. Hatha Yoga - its Philosophy and Practices i. Hatha Yoga, its meaning, definition, aims & objectives, misconceptions, Yoga Siddhikara and Yoga Vinashaka Bhavas ii. The origin of Hatha Yoga, Hatha Yogic literature, Hatha Yogic Practices iii. -

Prana and Pranayama Swami Niranjananda

Prana and Pranayama Swami Niranjanananda Saraswati Yoga Publications Trust, Munger, Bihar, India © Bihar School of Yoga 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from Yoga Publications Trust. The terms Satyananda Yoga® and Bihar Yoga® are registered trademarks owned by International Yoga Fellowship Movement (IYFM). The use of the same in this book is with permission and should not in any way be taken as affecting the validity of the marks. Published by Yoga Publications Trust First edition 2009 ISBN: 978-81-86336-79-3 Publisher and distributor: Yoga Publications Trust, Ganga Darshan, Munger, Bihar, India. Website: www.biharyoga.net www.rikhiapeeth.net Printed at Thomson Press (India) Limited, New Delhi, 110001 Dedication In humility we offer this dedication to Swami Sivananda Saraswati, who initiated Swami Satyananda Saraswati into the secrets of yoga. II. Classical Pranayamas 18. Guidelines for Pranayama 209 19. Nadi Shodhana Pranayama 223 20. Tranquillizing Pranayamas 246 21. Vitalizing Pranayamas 263 Appendices A. Supplementary Practices 285 B. Asanas Relevant to Pranayama 294 C. Mudras Relevant to Pranayama 308 D. Bandhas Relevant to Pranayama 325 E. Hatha Yoga Pradipika Pranayama Sutras 333 Glossary 340 Index of Practices 353 General Index 357 viii Introduction he classical yogic practices of pranayama have been Tknown in India for over 4,000 years. In the Bhagavad Gita, a text dated to the Mahabharata period, the reference to pranayama (4:29) indicates that the practices were as commonly known during that period as was yajna, fire sacrifice. -

Yogic Techniques in Classical Hatha Yoga Texts: a Comparative Perspective

www.ijcrt.org © 2018 IJCRT | Volume 6, Issue 1 January 2018 | ISSN: 2320-2882 Yogic Techniques in Classical Hatha Yoga Texts: A Comparative Perspective (With Reference to Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Gheranda Samhita and Siva Samhita) Kommareddy Sravani U. Sadasiva Rao Ad-hoc Faculty Guest Faculty MA Yoga & Consciousness Department of Yoga & Consciousness Andhra University Andhra University Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India Abstract Hatha Yoga, also called as “Forceful Yoga” is a path of Yoga, whose objective is to transcend the egoic consciousness and to realize the Self, or Divine Reality. However, the psycho spiritual technology of Hatha Yoga is predominantly focused on developing the body‟s potential so that the body can withstand the onslaught of transcendental realization. Mystical states of consciousness can have a profound effect on the nervous system and the rest of the body. Nevertheless, the experience of ecstatic union occurs in the embodied state. This fact led to the development of Hatha Yoga. The founder of Hatha Yoga, Matsyendranath and his followers called, to steel the body, to bake it well, as the texts say. This paper attempts to outline the techniques and tools of Hatha Yoga mentioned in the Classical Yoga texts, viz., Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Gheranda Samhita and Siva Samhita. The limbs of Hatha Yoga, i.e., Shatkarmas, Asanas, Pranayama, Bandhas, Mudras, Pratyahara, Dhyana and Samadhi have been elaborated in these texts by their respective authors with minor variations in their sequence, names, methods following their own style. This paper enables the reader to overview the multitude of Hatha yoga techniques, their Sanskrit names, and sequence with reference to the classical texts of hatha yoga mentioned above. -

Download the Book from RBSI Archive

About this Document by A. G. Mohan While reading the document please bear in mind the following: 1. The document seems to have been written during the 1930s and early 40s. It contains gems of advice from Krishnamacharya spread over the document. It can help to make the asana practice safe, effective, progressive and prevent injuries. Please read it carefully. 2. The original translation into English seems to have been done by an Indian who is not proficient in English as well as the subject of yoga. For example: a. You may find translations such as ‘catch the feet’ instead of ‘hold the feet’. b. The word ‘kumbhakam’ is generally used in the ancient texts to depict pranayama as well as the holdings of the breath. The original translation is incorrect and inconsistent in some places due to such translation. c. The word ‘angulas’ is translated as inches. Some places it refers to finger width. d. The word ‘secret’ means right methodology. e. ‘Weighing asanas’ meaning ‘weight bearing asanas’. 3. While describing the benefits of yoga practice, asana and pranayama, many ancient Ayurvedic terminologies have been translated into western medical terms such as kidney, liver, intestines, etc. These cannot be taken literally. 4. I have done only very minimal corrections to this original English translation to remove major confusions. I have split the document to make it more meaningful. 5. I used this manuscript as an aid to teaching yoga in the 1970s and 80s. I have clarified doubts in this document personally with Krishnamacharya in the course 2 of my learning and teaching. -

Premodern Yoga Traditions and Ayurveda: Preliminary Remarks on Shared Terminology, Theory, and Praxis

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SOAS Research Online History of Science in South Asia A journal for the history of all forms of scientific thought and action, ancient and modern, in all regions of South Asia Premodern Yoga Traditions and Ayurveda: Preliminary Remarks on Shared Terminology, Theory, and Praxis Jason Birch School of Oriental and African Studies, London University MLA style citation form: Jason Birch. “Premodern Yoga Traditions and Ayurveda: Preliminary Remarks on Shared Terminology, Theory, and Praxis.” History of Science in South Asia, 6 (2018): 1–83. doi: 10.18732/hssa.v6i0.25. Online version available at: http://hssa-journal.org HISTORY OF SCIENCE IN SOUTH ASIA A journal for the history of all forms of scientific thought and action, ancient and modern, inall regions of South Asia, published online at http://hssa-journal.org ISSN 2369-775X Editorial Board: • Dominik Wujastyk, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada • Kim Plofker, Union College, Schenectady, United States • Dhruv Raina, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India • Sreeramula Rajeswara Sarma, formerly Aligarh Muslim University, Düsseldorf, Germany • Fabrizio Speziale, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – CNRS, Paris, France • Michio Yano, Kyoto Sangyo University, Kyoto, Japan Publisher: History of Science in South Asia Principal Contact: Dominik Wujastyk, Editor, University of Alberta Email: ⟨[email protected]⟩ Mailing Address: History of Science in South Asia, Department of History and Classics, 2–81 HM Tory Building, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, T6G 2H4 Canada This journal provides immediate open access to its content on the principle that making research freely available to the public supports a greater global exchange of knowledge.