I:\Eastern Anthropologist\No 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Knowledge of Processing and Value Addition to Dromedary Camel Wool

Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 10(2), April 2011, pp. 316-318 Traditional knowledge of processing and value addition to dromedary camel wool Khem Chand, Jangid BL* & Rohilla PP Central Arid Zone Research Institute (ICAR), Regional Research Station, Pali-Marwar 306401, Rajasthan E-mail: [email protected] Received 18.08.2008; revised 15.01.2009 The paper describes Raika camel breeders’ traditional knowledge about value addition to dromedary camel wool. The information was collected through personal interview and observation among Raika camel breeders in Pali district of Rajasthan. Though, wool is not a product of very high economic value among the products of camel production system but breeders add value to it by investing their free time and prepare/ get prepared ropes, rugs and carpets from it. These are important household items for camel breeding profession and their day to day life. Keywords: Dromedary camel, Traditional wool processing, Raika , Rajasthan IPC Int. Cl. 8: D01 The camel ( Camelus romedaries ) is an important information. The information compiled during 2008 is animal component of the fragile desert ecosystem. based on the discussion with Aman Baa, Jawan Bhai, With its unique bio-physiological characteristics, the Babu Lal, Dhanna Ram, Suja Ram, Jeeva Ram, camel has become an icon of adaptation to Gamer Ram, Gokal Ram, Ada Ram, Arjun Ram, Pusa challenging ways of living in arid and semi-arid Ram, Babar Ram, Raja Ram, Sangram Ram, Shankar regions. The proverbial Ship of Desert earned its Ram, Oonkar Ram, Gamer Ram, Suja Ram/ Sanwalji, epithet on account of its indispensability as a mode of Harlal, Mohan Ram, Raghunath Ram, Mangla Ram, transportation and draught power in desert but the Mangi Lal, and Foola Ram, camel breeders, residents utilities are many and are subject to continuous social of village Anji ki Dhani , in tehsil Marwar Junction, and economic changes. -

Ajmer, Pali and Rajsamand Districts 2 2

72°40'0"E 72°50'0"E 73°0'0"E 73°10'0"E 73°20'0"E 73°30'0"E 73°40'0"E 73°50'0"E 74°0'0"E 74°10'0"E 74°20'0"E 74°30'0"E 74°40'0"E 74°50'0"E 75°0'0"E 75°10'0"E 75°20'0"E 75°30'0"E N N " " 0 0 GEOGRAPHICAL AREA ' ' 0 0 ° ° 7 7 2 2 AJMER, PALI AND ± RAJSAMAND DISTRICTS N N " " KEY MAP 0 0 ' ' 0 0 5 5 ° ° 6 6 2 Roopangarh 2 ! ¤£7 Karkeri ! Sursura ! N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 4 4 ° Á! ° 6 6 2 2 Á! Bandar Seendri R A J A S T H A N ! Kishangarh Á(! Á! Á!CA-06 Á! ¤£89 Gagwana ! ! N AJMER Á N " " 0 0 ' Á! ! Á! CA-01 ' 0 Pushk!ar Ghooghra 0 3 (! 3 ° Á!Ganahera ° 6 KISHANGARH 6 2 Ajmer 2 Govindgarh (! Á! Arain ! Boraj-Kazipura .! (! ! (! Á! ! Badlya Somalpur Ajmer Srinagar er ! iv Peesangan R ! Lambiya ! Daurai (Rural) ! Á! ni Á! Lu ¤£7 E Anandpur Kalu With Chak Á! ! CA-07 448 N ! ¤£ CA-05 N " Saradhana Á " 0 ! ! 0 ' PEESANGAN Á! Á ' 0 Rabariyas NASIRABAD 0 2 ! 2 Total Geographical Area (Sq Km) 25,523 ° ! Á! ° 6 Ras 6 Nimbol Baloonda ! 2 ! Á Nasirabad Cantt 2 ! £59 Balara ¤ Jethana Á! (! Ramsar No. of Charge Area 25 ! 158 ! ! ! CA-25 ¤£ Á ! Bidkachiyawas JAITARAN ! Derathoo Total Household 11,56,067 Á! L i ¤£48 lr Jaitaran i Total Population 57,77,222 R ! (! i Á v ! N Á N e " " r 0 0 ' Á! ' 0 Á! A J M E R 0 1 Nimaj 1 ° ! ° CHARGE CHARGE 6 Tantoti 6 ! 2 !Bandanwara ¤£26 2 NAME NAME Noondri Medratan Á! CA-02 CA-24 ! AREA ID AREA ID i ! Á! ad Kushalpura Á (! Masooda SARWAR a N ! RAIPUR ! Jooniya iy Atpara ¤£25 ¤£5 ! CA-01 Kishangarh CA-14 Rajsamand d ! Deoli Kalan ! Á! Beawar Re ! Bar Á! Á! Bhinay (! Sarwar Raipur ! CA-02 Sarwar CA-15 Nathdwara ! CA-08 Peepaliya -

District Census Handbook, 15 Pali, Part X a & X B, Series-18, Rajasthan

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES 18 RA.JASTHAN PARTS XA. XB DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK IS. PALl DISTRICT v. S. VERMA OF THE INDIAN AOMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Olr~ctor of Census Operations. RaJaschan Th. motif on the cover Is a montage presenting constructions typifying the rural and IIrbaa areas. set a,alnst a background formed by specimen Census nodonal maps of a ......n and a rural blCKk. The drawing hal been specially made for us by Shrl Paras Bhansall. LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Census of India 1971-Series-18 Rajasthan is being published in the following parts: Government of India Publications Part I-A General Report. Part I-B An analysis of the demographic, social, cultural and migration patterns. Part I-C Subsidiary Tables. Part II-A General Population Tables. Part II-B Economic Tables. Part II-C(i) Distribution of Populr.tion, Mother Tongue and Religion, Scheduled Castes &: Scheduled Tribes. Part II-C(ii) Other Social & Cultural Tables and Fertility Tables. Tables on Household Composition, Single Year Age, Marital Status, Educational Levels, Scheduled Castes &: Scheduled Tribes. etc., Bilingualism. Part III-A Report on Establishments. Part III-B Establishment Tables. Part IV Housing Report and Tables. Part V Special Tables and Notes on Scheduled Castes &: Scheduled Tribes. Part VI-A Town Directory. Part VI-B Special Survey Report on Selected Towns. Part VI-C Survey Report on Selected Villages. Part VII Special Report on Graduate and Technical Personnel. Part VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration. } F fli' I I Part VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation. or 0 cia use on y. Part IX Cenbus Atlas. -

District Survey Report of Pali District

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF PALI DISTRICT 1.INTRODUCTION Pali District has an area of 12387 km². The district lies between 24° 45' and 26° 29' north latitudes and 72°47' and 74°18' east longitudes. The Great Aravali hills link Pali district with Ajmer, Rajsamand, Udaipur and Sirohi Districts. Western Rajasthan's famous river Luni and its tributaries Jawai, Mithadi, Sukadi, Bandi and Guhiabala flows through Pali district. The Largest dams of this area Jawai Dam and Sardar Samand Dam are also located in Pali district. While plains of this district are 180 to 500 meters above sea level, Pali city the district headquarter, is situated at 212 meters above sea level. While the highest point of Aravali hills in the district measures 1099 meters, the famous Ranakpur temples are situated in the footsteps of Aravalis. Parashuram Mahadev temple, a place of worship for millions of devotees of Lord Shiva, is also located in the Pali district on the hights of aravali range. District is well connected by rail i.e., Delhi- Ahemdabad section of North-Western Railway and Jodhpur-Marwar section of North-Western Railway. A net-work of roads is spread over the district connecting many villages and important cities of Rajasthan like Jodhpur, Jaipur Ajmer, Sirohi, Udaipur etc. 2.OVER VIEW OF MINING ACTIVITY IN THE DISTRICT. The mineral wealth of the district is largely non metallic. The chemical grade limestone, Quartz, Feldspar and Calcite produced in the district is also known for their quality. Other minerals are Asbestos, Soap stone, Magnesite, Gypsum, Marble and Barytes. The district has substantial resources of Quartz feldspar, Asbestos. -

Public Works Department

PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT PPP DIVISION Public Disclosure Authorized Government of Rajasthan Public Disclosure Authorized DRAFT RESETTLEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK WORLD BANK – FUNDED PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized RAJASTHAN STATE HIGHWAY ROAD DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Draft Resettlement Policy Framework Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................. 4 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Project Description ...................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Project Components and Scope of Land Acquisition .................................................. 5 2. OBJECTIVES AND PRINCIPLES OF RESETTLEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK ................ 8 2.1 Purpose of Resettlement Policy Framework ............................................................... 8 2.2 Objective of the Resettlement Policy Framework ....................................................... 8 2.3 Basic Principles of the Policy Framework .................................................................. 9 2.4 Preparation of SIA/SIMP and RAP ........................................................................... 10 2.5 Sub Project Approval ................................................................................................ 11 3 LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK ..................................................................................... -

Widening E-Goveranan

Widening e-Governance Canvas Selected e-Governance Initiatives in India A selection of major e-Governance initiatives at State, District, Department and Projects level including those of Central Government, which competed for coveted CSI-Nihilent e-Governance Awards for the year 2010-11.The Awards were presented during 46th Annual Convention of Computer Society of India by Special Interest group (SIG) on e-Governance at Ahmedabad on 2nd December 2011. – Editors About CSI The Computer Society of India (CSI) is the largest association of information technology professionals in India, with over 70,000 members comprising software developers, scientists, academicians, project managers, CIOs, CTOs and IT vendors, among others. The society has 69 chapters spread across the length and breadth of the country. Being closely associated with students, the Society has developed a well-established network of nearly 381 student branches. The purposes of the Society are scientific and educational, directed towards the advancement of the theory and practice of Computer Science & IT. For more information, please visit www.csi-india.org Special Interest Group on e-Governance (CSI-SIGeGov) has been set up within CSI to focus on e-Governance activities in the country. SIG activities include Knowledge sharing with all stakeholders through holding conferences, Knowledge sharing summits and recognizing efforts/ contributions of Central/State level Government entities by way of e-Governance Awards (www.csinihilent- egovernanceawards.org) For more Details Visit http://www.csi-sigegov.org About Nihilent Nihilent is a global consulting and solutions integration company using a holistic and systems appoach to problem solving. Headquartered in Pune, India, Nihilent has extensive experience in international consulting, IT outsourcing and IT services. -

Aadhaar Operator List : Dist - Pali

Aadhaar Operator List : dist - Pali SRNO AADHAAR OPERATOR Mobile No. Center ADDRESS Block Last Update Date (DD/MM/YYYY) 1 HARISH KUMAR 9950820001 ask latada, bali, pali, rajasthan BALI lunawa, bus stand lunawa, Pali, Bali, Lunawa, 2 Mahipal Singh Sonigara 9829275758 BALI 06/08/2017 Rajasthan - 306706 e mitra, bijapur, Pali, Bali, Beejapur, Rajasthan 3 Sonu Kumari 7597843597 BALI 09/08/2017 - 306707 bhawani computer, khimel, Pali, Bali, 4 Sukh Dev 9887206474 BALI 04/08/2017 Kheemel, Rajasthan - 306115 RAUNAK E MITRA, BANK ROAD, Pali, Bali, Bali, 5 Ajarudin 8440851678 BALI 09/08/2017 Rajasthan - 306701 chandan kanwar, chanchori house aaimata 6 Chandan Kanwar 9829875763 colony near court bali distt pali rajasthan, Pali, BALI 03/08/2017 Bali, Bali, Rajasthan - 306701 mangalam, falna road bali, Pali, Bali, Bali, 7 Devendra Singh 9509204611 BALI 06/08/2017 Rajasthan - 306701 priyanshi emitra, main bazar beda, Pali, Bali, 8 Jagdev Singh 9785343048 BALI 09/08/2017 Bera, Rajasthan - 306126 shiwam, vader vas mokampura, Pali, Bali, 9 Parmeshwar Singh 9782013985 BALI 09/08/2017 Mokhampura, Rajasthan - 306115 CLASSIC E SERVICE, INDRA COLONY FALNA, 10 MOH YUNUS 9828085992 BALI BALI, PALI, RAJATHAN atal sewa kendra desuri, atal sewa kendra vpo 11 Suresh Kumar 9660375553 desuri dist pali rajasthan, Pali, Desuri, Desuri, DESURI 03/08/2017 Rajasthan - 306703 IT CENTRE, IT CENTRE, Pali, Desuri, Sansari, 12 Altf Hussain 7665102001 DESURI 01/08/2017 Rajasthan - 306022 vijaya laxmi, goro ka bas, Pali, Desuri, Sadri 13 Dinesh Kumar 9782350852 DESURI 09/08/2017 -

District-Pali

Medical Health & FW Department Govt of Rajasthan FACILITYWISE SCORE CARD FOR DISTRICT HOSPITAL, CHC & PHC DISTRICT-PALI Period - April 2018 to March 2019 Data Source: - PCTS (Form 6,7 &), e- Aushadhi, OJAS, e- Mail Summary of District 1. District Hospital Name of Hospital Marks obt. Out of 91 Rank in the State Govt Bangur Hopital Pali 54.48 8 2. CHCs Total 21 Marks Obtained Grade Performance No of CHCs in grade >80% A+ Outstanding 0 >70 - <=80% A Very Good 4 >60- <=70% B Good 10 >50- <=60% C Average 5 <50% D Unsatisfactory 2 Top 5 CHCs Last 5 CHCs Rank in Rank in Name of CHC % Achi. Name of CHC % Achi. State State 1 Koselave 74.36 36 17 Bagri Nagar 58.97 275 2 Takhatgarh 73.11 54 18 Nimaj 53.88 343 3 Sojatroad 72.14 64 19 Kusalpura 50.13 408 4 Desuri 70.78 83 20 Khod 41.84 483 5 Raipur 68.66 112 21 Manihari 29.56 526 3. PHCs Total 83 Marks Obtained Grade Performance No of CHCs in grade >80% A+ Outstanding 13 >70 - <=80% A Very Good 10 >60- <=70% B Good 12 >50- <=60% C Average 21 <50% D Unsatisfactory 27 Top 5 CHCs Last 5 CHCs Rank in Rank in Name of PHC % Achi. Name of CHC % Achi. State State 1 Chandaval 95.12 1695 79 Hariyamali 32.74 1773 2 Boosi 91.92 1696 80 Mohrai 30.3 1774 3 Anandpur Kalu 91.8 1697 81 Bhumbaliya 30.16 1775 4 Novi 90.63 1698 82 Asarlai 29.18 1776 5 Gundoj 88.78 1699 83 Ramgarh Chang 27.22 1777 Medical,Health & FW Department Govt of Rajasthan MONTHLY REPORT CARD OF DH,SDH,SH April 2018 to March District :- Pali Month 2019 Name of Hospital :- Govt Bangur Hopital Pali No of Beds 300 Name of Incharge :- Dr. -

Workshop Report 3

Saving National-level Workshop Rajasthan’s Camel Herds: Identifying the Saving Rajasthan’s Camel Herds Options for Recovering The Perspective of Camel Breeders Pasture Opportunities National-level workshop, 17-19 November 2004 Sadri, Rajasthan, India Workshop Report Compiled by The LIFE Arun Srivastava, Ilse Köhler-Rollefson, Hanwant Initiative Singh Rathore, Uttra Kothari Local Livestock for Lokhit Pashu-Palak Sansthan Empowerment P.O. Box 1, Sadri 306702, District Pali, Rajasthan Tel/Fax 02934-285086, email [email protected] of Rural People www.lifeinitiativ Table of contents Table of contents ...........................................................................................2 Executive summary .......................................................................................3 Introduction....................................................................................................4 Background....................................................................................................6 Decline in camel population.......................................................................................... 6 Socio-economic context of camel breeding and keeping............................................. 6 Reasons for the decline of the camel population ......................................................... 7 Institutional context....................................................................................................... 8 Workshop objectives.....................................................................................9 -

World Bank Document

PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT PPP DIVISION Public Disclosure Authorized Government of Rajasthan DRAFT CONSOLIDATED SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT / SOCIAL IMPACT MANAGEMENT PLAN Public Disclosure Authorized CUM RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN WORLD BANK – FUNDED PROJECT RAJASTHAN STATE HIGHWAY ROAD DEVELOPMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROGRAMME Package-1 Banar - Bhopalgarh - Kuchera Public Disclosure Authorized Package-2 Bhawi-Pipar-Khimsar (H-IV) section Package 3 Jodhpur - Marwar Junction- Jojawar Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Project Background ............................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Land .................................................................................................................................... 7 1.3 Flora and Fauna of Rajasthan .............................................................................................. 7 1.4 Demographics and Administration of Rajasthan ................................................................ 8 1.5 Literacy ............................................................................................................................... 8 1.6 Economy ............................................................................................................................. 8 1.6 Administrative districts ...................................................................................................... -

CSC E Governance Services Ltd

CSC e_Governance Services Ltd. Sr.No Agent Name Agent Address Dist name State name Pincode 1 Aayuesh Goel Kalsi Road Dakpathar Vikasnagar Dehradun Dehradun Uttarakhand 248125 Gandhi Bomma Center Road, Beside Vro Office, Alamuru, East 2 Achanta Srinivasarao East Godavari Andhra Pradesh 533233 Godavari, Ap 3 Ajay Joshi Pitgara, Badnawar, Dist. Dhar Dhar Madhya Pradesh 454660 4 Ajay Kumar Noukri Point, Rani Bajaar,Nohar Hanumangarh Rajasthan 335523 5 Akhilesh Thakur Court Road Dhar Dhar Madhya Pradesh 454446 4-125, Gandhi Center, Paritala, Kanchikacherla, Krishna, Andhra 6 Akula Narasimhaswamy Krishna Andhra Pradesh 521180 Pradesh 7 Anil Kumar Manjeri Csc Center,Poonthottathil Tower Nilambur Road Manjeri Malappuram Kerala 676121 8 Anil Namta Yashmehul Studio,Bagbera Colony J.P. Road East Singhbhum Jharkhand 831002 9 Ankit Saini Sarthak Computer Education Holi Tiba Tijara Alwar Rajasthan 301411 10 Arvind Madan Teli Near Bus Stand, Jalgaon Road, Jamner, Jalgaon Jalgaon Maharashtra 424206 11 Aziz Gohar Khan Tareen Vill Thapal, Najibabad Distt Bijnor Up Bijnor Uttar Pradesh 246763 12 Balwinder Singh Near Sub Tehsil, Alal Road Sherpur Sangrur Punjab 148025 13 Basavaraj Hiremath Maheshwar Digital,509, Main Road Pathade Galli Akkol-591211 Belgaum Karnataka 591211 14 Bhera Ram Prime Computers Opp. Rajasthan Marudhar Bank Bilara Jodhpur Jodhpur Rajasthan 342602 15 Chekka Suresh Kumar 7-135 Main Road Opp Sbi Rayavaram, East Godavari, Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Andhra Pradesh 533346 16 Chitikesu Harisuman H No 8-1-70 ,Opp.Mamatha Hospital , Jammikunta -

STATE BANK of BIKANER and JAIPUR.Pdf

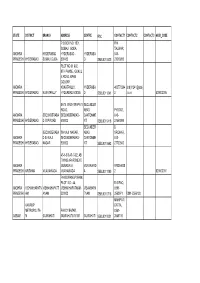

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE P.O.BOX NO. 1501, R H SOMAJI GODA, TALWAR, ANDHRA HYDERABAD HYDERABAD - HYDERABA 040- PRADESH HYDERABAD SOMAJI GUDA 500482 D SBBJ0010625 23310205 PLOT NO.31 &32 9TH PHASE, GOKUL X ROAD, KPHB COLONY, ANDHRA KUKATPALLY, HYDERABA 402770284 sbbj11241@sbbj PRADESH HYDERABAD KUKATPALLY HYDERBAD-500085 D SBBJ0011241 2 .co.in 500003005 8573, RASHTRAPATI SECUNDER ROAD, ABAD P K DAS, ANDHRA SECUNDERABA SECUNDERABAD - CANTONME 040- PRADESH HYDERABAD D R P ROAD 500003 NT SBBJ0010418 27540399 SECUNDER D SECUNDERABA SHIVAJI NAGAR, ABAD SRIDHAR, ANDHRA D SHIVAJI SECUNDERABAD - CANTONME 040- PRADESH HYDERABAD NAGAR 500003 NT SBBJ0010642 27702842 45-1-3/3,45-1-3/2, AB TWINS APARTMENT, ANDHRA GUNADALA, VIJAYAWAD 970346038 PRADESH KRISHNA VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA A SBBJ0011180 2 520003001 PANDURANGPURAM, PLOT NO - 44, B G RAO, ANDHRA VISHAKHAPATN VISHAKHAPATT VISHAKHAPATNAM - VISAKHAPA 0891- PRADESH AM ANAM 530003 TNAM SBBJ0010716 2562971 0891-2556138 MAHIPATI KAMRUP DATTA, METROPOLITA FANCY BAZAR, 0361- ASSAM N GUWAHATI GUWAHATI-781001 GUWAHATI SBBJ0010001 2546110 First Floor, Vill : Surar,PO:Pirauta, Opposite NTPC Power Plant, PS : NTPC Khaira, Nabinagar, 06332- Surar, Nabinagar Aurangabad, Bihar, AURANGAB 963162646 sbbj11225@sbbj BIHAR AURANGABAD Block Pin-824303 AD SBBJ0011225 9 .co.in 824003501 JAISWAL TOWER, RAIBAHADUR SHIV SHANKAR SAHAI ROAD, BHIKHANPUR, 0641 BHAGALPUR, BIHAR - BHAGALPU 963162646 BIHAR BHAGALPUR BHAGALPUR 812001 R SBBJ0011414 9 812003002 BIHTA MAIN ROAD,OPPOSITE