Agenda Item 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congratulations

Congratulations Congratulations on gaining your award from Sheffield Hallam University. Your graduation ceremony is a perfect opportunity to mark your outstanding achievement and we look forward to celebrating this proud moment with you. Held in Sheffield’s stunning City Hall, the occasion is sure to be one you and your guests will remember for years to come. This booklet will help you prepare for and make the most of your graduation day, so please take some time to have a look through it. Graduation day will mark new and exciting beginnings for you. As a community of talented staff, students, alumni and partners we are proud of the role we have played in your success. As a University we have a genuine ambition to transform lives through outstanding research and the highest quality teaching, reflected by the fact we have just been named as the University of the Year for Teaching Quality by The Times Good University Guide. For almost two centuries, Sheffield Hallam and its predecessor institutions have exercised a powerful impact on the city, region and world. Indeed Universities have never been more important to more people than they are today. Around the world, individuals, governments and society increasingly look to universities to provide answers to the toughest questions and to help people like you realise their aspirations. The University continues to develop its postgraduate and professional courses which can be followed in a variety of ways, including distance learning – so you can continue to develop your skills and knowledge with Sheffield Hallam long into the future. Graduation also marks the start of a new relationship between you and the University as alumni – a lifelong connection with us and your former classmates. -

Neighbourhoods Update Page 13 Page Nicki Doherty Director of Delivery Care Outside of Hospital + Dr Anthony Gore Clinical Director Care Outside of Hospital

Neighbourhoods Update Page 13 Nicki Doherty Director of Delivery Care Outside of Hospital + Dr Anthony Gore Clinical Director Care Outside of Hospital NHS Sheffield CCG Agenda Item 7 Page 14 What is a Neighbourhood.. a geographical population of around 30-50,000 people Page 15 supported by joined up health, social, voluntary sector and wider services to support people to remain independent , safe and well in their community. Why Neighbourhoods? • General Practice at Scale Page 16 • Wider integrated working across the health and social care system • Targeting Care to priority patient groups • Managing Resources • Empowering Neighbourhoods 16 Neighbourhoods Across Sheffield 4 in Central City 4 in Hallam & South High Green 3 in North 5 in West Upper Don Valley SAPA - North2 - West4 North2 Darnall - Peak Edge GPA1 - SSHG Dovercourt Surgery 70 GPA1 Duke Medical Centre 29 West 6 Hillsborough East Bank Medical Centre 68 Manor Park Medical Centre 67 Townships II Norfolk Park Medical Practice 56 - Hillsborough Park Health Centre 18 - Upper Don Valley Student Page 17 White House Surgery 39 Porter Valley North 2 Townships I Burngreave Surgery 12 - Porter Valley Dunninc Road Surgery 48 City Centre Carrfield Firth Park Surgery 25 SSHG Page Hall Medical Centre 9 Pitsmoor Surgery 58 Sheffield Medical Centre 62 Peak Edge Carrfield Shiregreen Medical Centre 82 Carrfield Medical Centre 73 The Flowers Health Centre 27 Gleadless Medical Centre 40 Upwell Street Surgery 32 Upper Don Valley SAPA Heeley Green Surgery 80 Wincobank Medical Centre 13 Deepcar Medical -

KES Newsletter May 2019

King Edward VII School w: kes.sheffield.sch.uk e: [email protected] facebook.com/KESSheffield twitter.com/KESSheffield NEWSLETTER May 2019 Welcome to the second School newsletter of 2018-2019. King Edward VII School has had a very successful year so far and the bumper edition of this newsletter will make compelling reading for School members and the wider community. The articles, and shorter contributions, provide a genuine insight into the philosophy, ethos and life of the School, the opportunities available to students, the unconditional commitment of staff and governors and the legacy that the School has had on Old Edwardians. You will have the opportunity to read about how students are maintaining academic excellence in various subjects, alongside maintaining the tradition of success in many sports, art and music. Partnership work with external organisations, particularly with the University of Sheffield and Sheffield Hallam University, feature strongly in this newsletter. Climate change is the global issue that has galvanised young people to act as part of the coordinated Youth Strike 4 Climate movement. One student has documented her views in this newsletter. September 2019 will mark the fiftieth anniversary since girls first joined the School in the Sixth Form in 1969! The School intends to mark this significant occasion during the autumn term. If you were one of the first girls to join the School or if you have any information relevant to this special period in the School’s history, please contact the School. If you have an article that would be of interest to our School community, please email it to [email protected] for consideration. -

Stephen Mallinder. “Sheffield Is Not Sexy.”

Nebula 4.3 , September 2007 Sheffield is not Sexy. By Stephen Mallinder Abstract The city of Sheffield’s attempts, during the early 1980s, at promoting economic regeneration through popular cultural production were unconsciously suggestive of later creative industries strategies. Post-work economic policies, which became significant to the Blair government a decade later, were evident in urban centres such as Manchester, Liverpool and Sheffield in nascent form. The specificity of Sheffield’s socio-economic configuration gave context, not merely to its industrial narrative but also to the city’s auditory culture, which was to frame well intended though subsequently flawed strategies for regeneration. Unlike other cities, most notably Manchester, the city’s mono-cultural characteristics failed to provide an effective entrepreneurial infrastructure on which to build immediate economic response to economic rationalisation and regional decline. Top-down municipal policies, which embraced the city’s popular music, gave centrality to cultural production in response to a deflated regional economy unable, at the time, to sustain rejuvenation through cultural consumption. Such embryonic strategies would subsequently become formalised though creative industry policies developing relationships with local economies as opposed to urban engineering through regional government. Building upon the readings of industrial cities such as Liverpool, New Orleans and Chicago, the post-work leisure economy has increasingly addressed the significance of the auditory effect in cities such as Manchester and Sheffield. However the failure of the talismanic National Centre for Popular Music signifies the inherent problems of institutionalizing popular cultural forms and resistance of sound to be anchored and contained. The city’s sonic narrative became contained in its distinctive patterns of cultural production and consumption that ultimately resisted attempts at compartmentalization and representation through what became colloquially known as ‘the museum of popular music’. -

1 SHEFFIELD CITY TRUST Management Report Relating To

SHEFFIELD CITY TRUST Management Report relating to, and deemed to be part of, the annual financial report of Sheffield City Trust (the “charity”) for the year ended 31 March 2017 REPORT The trustees, who act as directors for the purpose of company law, present their management report for the period ended 31 March 2017. Purpose of the charity The objects of the charity are as detailed in the charity’s governing document, its Memorandum of Association. 1 An object of the charity is to promote the benefit of the inhabitants of South Yorkshire and surrounding counties by the provision of facilities for recreation and leisure time occupation in the interest of social welfare. The charity has continued in its policies of providing recreational and other leisure facilities of a high standard and as economically as possible. The charity seeks to encourage high levels of use by the community with policies that encourage wide public access. There has been no material change in these policies over the relevant period. 2 A further object of the charity is to promote and preserve good physical and mental health. The objective is pursued by encouraging high levels of use of recreational and leisure facilities by the community. In addition, the charity has a policy of carrying out ad hoc initiatives and giving financial support to appropriate projects which has been continued during the period. 3 Further objects of the charity include the encouragement of the arts and the acquisition, preservation, restoration and maintenance of buildings of historic -

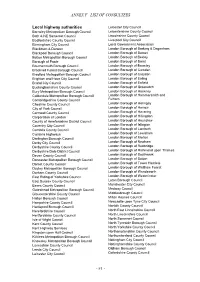

Annex F –List of Consultees

ANNEX F –LIST OF CONSULTEES Local highway authorities Leicester City Council Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Leicestershire County Council Bath & NE Somerset Council Lincolnshire County Council Bedfordshire County Council Liverpool City Council Birmingham City Council Local Government Association Blackburn & Darwen London Borough of Barking & Dagenham Blackpool Borough Council London Borough of Barnet Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Bexley Borough of Poole London Borough of Brent Bournemouth Borough Council London Borough of Bromley Bracknell Forest Borough Council London Borough of Camden Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Croydon Brighton and Hove City Council London Borough of Ealing Bristol City Council London Borough of Enfield Buckinghamshire County Council London Borough of Greenwich Bury Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hackney Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hammersmith and Cambridgeshire County Council Fulham Cheshire County Council London Borough of Haringey City of York Council London Borough of Harrow Cornwall County Council London Borough of Havering Corporation of London London Borough of Hillingdon County of Herefordshire District Council London Borough of Hounslow Coventry City Council London Borough of Islington Cumbria County Council London Borough of Lambeth Cumbria Highways London Borough of Lewisham Darlington Borough Council London Borough of Merton Derby City Council London Borough of Newham Derbyshire County Council London -

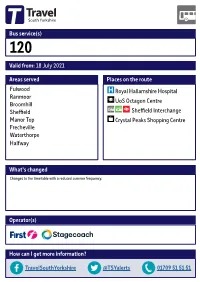

Valid From: 18 July 2021 Bus Service(S) What's Changed Areas Served Fulwood Ranmoor Broomhill Sheffield Manor Top Frecheville

Bus service(s) 120 Valid from: 18 July 2021 Areas served Places on the route Fulwood Royal Hallamshire Hospital Ranmoor UoS Octagon Centre Broomhill Sheffield Sheffield Interchange Manor Top Crystal Peaks Shopping Centre Frecheville Waterthorpe Halfway What’s changed Changes to the timetable with a reduced summer frequency. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for service 120 Walkley 17/09/2015 Sheeld, Tinsley Park Stannington Flat St Catclie Sheeld, Arundel Gate Sheeld, Interchange Darnall Waverley Treeton Broomhill,Crookes Glossop Rd/ 120 Rivelin Royal Hallamshire Hosp 120 Ranmoor, Fulwood Rd/ 120 Wybourn Ranmoor Park Rd Littledale Fulwood, Barnclie Rd/ 120 Winchester Rd Western Bank, Manor Park Handsworth Glossop Road/ 120 120 Endclie UoS Octagon Centre Ranmoor, Fulwood Rd/Riverdale Rd Norfolk Park Manor Fence Ô Ò Hunters Bar Ranmoor, Fulwood Rd/ Fulwood Manor Top, City Rd/Eastern Av Hangingwater Rd Manor Top, City Rd/Elm Tree Nether Edge Heeley Woodhouse Arbourthorne Intake Bents Green Carter Knowle Ecclesall Gleadless Frecheville, Birley Moor Rd/ Heathfield Rd Ringinglow Waterthorpe, Gleadless Valley Birley, Birley Moor Rd/ Crystal Peaks Bus Stn Birley Moor Cl Millhouses Norton Lees Hackenthorpe 120 Birley Woodseats Herdings Whirlow Hemsworth Charnock Owlthorpe Sothall High Lane Abbeydale Beauchief Dore Moor Norton Westfield database right 2015 Dore Abbeydale Park Greenhill Mosborough and Ridgeway 120 yright p o c Halfway, Streetfields/Auckland Way own r C Totley Brook -

Yorkshire and Humberside)

NOTES OF A MEETING OF THE STANDARDS COMMITTEE INDEPENDENT MEMBERS’ REGIONAL FORUM (YORKSHIRE AND HUMBERSIDE) 24 TH OCTOBER 2006 PRESENT: Mike Wilkinson - Leeds City Council Ann Becket - West Yorkshire Police Authority Martin Allingham - North East Lincolnshire Council Alan Carter - South Yorkshire Police Authority/South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Authority Gerald Burnett - Richmondshire District Council James Daglish - North Yorkshire County Council Cheryl Grant - Leeds City Council Peter Neale - Richmondshire District Council Lynn Knowles - Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council/West Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Authority John Ross - North East Derbyshire District Council Phil Marshall - West Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Authority Joyce Clarke - Humberside Fire and Rescue Authority Brian Cottingham - Kingston-upon-Hull City Council Keith Robinson - Kingston-upon-Hull City Council Dr Michael French - Harrogate Borough Council Richard Burton - South Yorkshire Police Authority William Stroud - Humberside Police Authority Mary Rose Barker - East Riding of Yorkshire Borough Council G Polley - East Riding of Yorkshire Borough Council Michael Andrew - Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council D G Hughes - Humberside Fire and Rescue Authority IN ATTENDANCE: Amy Bowler - Secretary to the Forum, Leeds City Council 1.0 Apologies for Absence and Welcome to New Members 1.1 The following apologies for absence were reported: Denise Wilson – North Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Authority Angela Bingham – South Yorkshire Police Authority George – Wakefield Metropolitan -

Community Connector

COMMUNITY The CONNECTOR A newsletter for people in Darnall, Tinsley, Attercliffe and Handsworth Welcome! We are excited to welcome you to the first edition of your local newsletter, covering homes in the Attercliffe, Darnall, Tinsley and Handsworth areas of Sheffield. A small group of local organisations have come together to work in partnership for the benefit of the community. We felt it important in these difficult times, to provide a space to share useful information, good new stories and help people connect to what is happening in their local area. If you have ideas for future editions, please get in touch with your suggestions to: [email protected] Welcome sign at High Hazels Park Enjoy! If you need a large print version of the newsletter, please contact us at the email address above, and we will provide one. This newsletter has been published and distributed thanks to funding from: Community Hub As your local Community Hub, Darnall Well Being are working closely with a range of services in the Darnall, Tinsley, Acres Hill and Handsworth areas to support the community during Covid-19. We can help you by offering: • A friendly chat • Signposting/sharing information • Help with sorting out access to food • Help with accessing medication • Reassurance about the best place to get help If you or someone you know would like support, please contact us by: Email: [email protected] or Phone: 0114 249 6315 or Text/Call: 07946 320 808 We will respond within one working day. If you need urgent help, you -

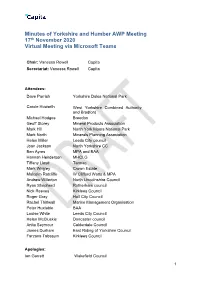

Minutes of Yorkshire and Humber AWP Meeting 17Th November 2020 Virtual Meeting Via Microsoft Teams

Minutes of Yorkshire and Humber AWP Meeting 17th November 2020 Virtual Meeting via Microsoft Teams Chair: Vanessa Rowell Capita Secretariat: Vanessa Rowell Capita Attendees: Dave Parrish Yorkshire Dales National Park Carole Howarth West Yorkshire Combined Authority and Bradford Michael Hodges Breedon Geoff Storey Mineral Products Association Mark Hill North York Moors National Park Mark North Minerals Planning Association Helen Miller Leeds City council Joan Jackson North Yorkshire CC Ben Ayres MPA and BAA Hannah Henderson MHCLG Tiffany Lloyd Tarmac Mark Wrigley Crown Estate Malcolm Ratcliffe W Clifford Watts & MPA Andrew Willerton North Lincolnshire Council Ryan Shepherd Rotherham council Nick Reeves Kirklees Council Roger Gray Hull City Council Rachel Thirlwall Marine Management Organisation Peter Huxtable BAA Louise White Leeds City Council Helen McCluskie Doncaster council Anita Seymour Calderdale Council James Durham East Riding of Yorkshire Council Farzana Tabasum Kirklees Council Apologies: Ian Garrett Wakefield Council 1 Chris Hanson Sheffield City Council Katie Gowthorpe East Riding of Yorkshire Council Vicky Perkin North Yorkshire County Council Item Description 1. Introductions and apologies 2. Minutes and actions of last meeting 3. Yorkshire & Humber AMR - ratification 4 Local Aggregate Assessments 5. Aggregate Minerals Survey update 2019 6. Planning White Paper 7. MPAs Update 8. Industry Update 9. MCHLG update 10. AOB 1. Introductions 1.1 Vanessa Rowell (VR) explained that Vicky Perkin has sent her apologies and therefore VR will be the Interim Chair for this meeting. VR Welcomed everyone to the meeting. 2. Minutes and actions of last meeting 2.1 VR went through the minutes from the last meeting asking if there were any comments on the minutes. -

16 Neighbourhoods Across Sheffield City 4 in Central 4 in Hallam & South 3 in North High Green 5 in West

16 Neighbourhoods Across Sheffield City 4 in Central 4 in Hallam & South 3 in North High Green 5 in West Upper Don Valley SAPA - North2 North2 Darnall - South West GPA1 GPA1 W4GPA Dovercourt Surgery 70 Hillsborough (West4) Duke Medical Centre 29 East Bank Medical Centre 68 Townships II - Hillsborough Manor Park Medical Centre 67 - Upper Don Valley Norfolk Park Medical Practice 56 Universities Park Health Centre 18 Porter Valley White House Surgery 39 Townships I North2 - Porter Valley Burngreave Surgery 12 City Centre Carrfield Dunninc Road Surgery 48 SWAC Firth Park Surgery 25 Page Hall Medical Centre 9 South West Pitsmoor Surgery 58 Sheffield Medical Centre 62 Carrfield Shiregreen Medical Centre 82 SAPA Upper Don Valley The Flowers Health Centre 27 Carrfield Medical Centre 73 Gleadless Medical Centre 40 Upwell Street Surgery 32 Barnsley Road Surgery 66 Deepcar Medical Centre 79 Wincobank Medical Centre 13 Heeley Green Surgery 80 Oughtibridge Surgery 20 Sharrow Lane Medical Centre 3 Buchanan Road Surgery 61 Townships I Valley Medical Centre 65 The Mathews Practice 22 Elm Lane Surgery 10 Crystal Peaks Medical Centre 50 University South West Mosborough Health Centre 76 Norwood Medical Centre 44 University Health Service Health Centre 46 Owlthorpe Medical Centre 49 Avenue Medical Practice 35 Southey Green Medical Centre 69 Porter Valley Sothall and Beighton Health Centres 36 Baslow Road And Shoreham Street Surgeries 23 The Health Care Surgery 77 Falkland House 7 Hackenthorpe Medical Centre 63 The Meadowgreen Group Practice 43 Greystones -

Monthly Trade & Industry Focus July 2014 Business MONTHLY How Sweet

The Star’s monthly trade & industry focus July 2014 Business MONTHLY How sweet... a Franco becomes crafty new way the Big Mac at to network PAGE 26 McDonald’s PAGE 3 Agriculture is a case of like father, FARMING STAYS like son: FAMILY MATTER PAGE 5 Lawyer shows her True Colours in our Smarten Up The Boss makeover: Page 23 2 THE STAR www.thestar.co.uk Wednesday, July 2, 2014 BUSINESS SHOWCASING BUSINESSES n innovative fit- Départ International Busi- Leaders of over 30 leading to track performance and Jo Davison – EDITOR ness system that ness Festival in Sheffield. businesses will be showcas- recovery. aspires to help Sport Tech Match is part ing their skills and services. Details of free workshops, win the global of a packed programme of MIE Medical Research seminars and conferences race is among the activity at the English In- Limited will be demonstrat- are at www.letour.york- technology being stitute of Sport from today ing FitQuest, an innovative shire.com/cycling-culture- Ashowcased at the Grand until Friday. instrument that can be used and-business. Le Tour - think of it as a giant selfie ’ll be honest. Since in the world swooping to- ditching my broth- wardS Attercliffe. er’S fake Raleigh The Tour de France is Chopper in a hedge on our patch. Not that because my Free- you’d know it. I went down Time to switch man’s flares kept Winco’s Newman Road and Igettingca ught in the chain, up the soon-to-be-legen- I haven’t cycled much.