Jane Van Nimmen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gustav Klimt: the Magic of Line

Page 1 OBJECT LIST Gustav Klimt: The Magic of Line At the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center July 3–September 23, 2012 All works by Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862–1918) unless otherwise specified 1. The Auditorium of the Old 4. Man in Three Quarter View (Study for Burgtheater, 1888-89 and 1893 Shakespeare's Theater), 1886-87 Watercolor and gouache Black chalk, heightened with white Unframed: 22 x 28 cm (8 11/16 x 11 in.) Unframed: 42.5 x 29.4 cm (16 3/4 x 11 Privatsammlung Panzenböck 9/16 in.) EX.2012.3.19 Albertina, Wien EX.2012.3.27 2. Profile and Rear View of a Man with Binoculars, Sketch of His Right Hand, 5. Head of a Reclining Young Man, Head 1888-89 in Lost Profile (Study for Black chalk, heightened with white, Shakespeare's Theater), 1887 87 on greenish paper Black chalk, heightened with white, Unframed: 45 x 31.7 cm (17 11/16 x 12 graphite 1/2 in.) Unframed: 44.8 x 31.4 cm (17 5/8 x 12 Albertina, Wien 3/8 in.) EX.2012.3.29 Albertina, Wien EX.2012.3.33 3. Man with Cap in Profile (Study for Shakespeare's Theater), 1886-87 6. Reclining Girl (Juliet), and Two Studies Black chalk heightened with white of Hands (Study for Shakespeare's Unframed: 42.6 x 29 cm (16 3/4 x 11 Theater), 1886-87 7/16 in.) Black chalk, stumped, heightened Albertina, Wien with white, graphite EX.2012.3.28 Unframed: 27.6 x 42.4 cm (10 7/8 x 16 11/16 in.) Albertina, Wien EX.2012.3.32 -more- -more- Page 2 7. -

African Masks

Gustav Klimt Slide Script Pre-slides: Focus slide; “And now, it’s time for Art Lit” Slide 1: Words We Will Use Today Mosaics: Mosaics use many tiny pieces of colored glass, shiny stones, gold, and silver to make intricate images and patterns. Art Nouveau: this means New Art - a style of decorative art, architecture, and design popular in Western Europe and the US from about 1890 to 1910. It’s recognized by flowing lines and curves. Patrons: Patrons are men and women who support the arts by purchasing art, commissioning art, or by sponsoring or providing a salary to an artist so they can continue making art. Slide 2 – Gustav Klimt Gustav Klimt was a master of eye popping pattern and metallic color. Art Nouveau (noo-vo) artists like Klimt used bright colors and swirling, flowing lines and believed art could symbolize something beyond what appeared on the canvas. When asked why he never painted a self-portrait, Klimt said, “There is nothing special about me. Whoever wants to know something about me... ought to look carefully at my pictures.” We may not have a self-portrait but we do have photos of him – including this one with his studio cat! Let’s see what we can learn about Klimt today. Slide 3 – Public Art Klimt was born in Vienna, Austria where he lived his whole life. Klimt’s father was a gold engraver and he taught his son how to work with gold. Klimt won a full scholarship to art school at the age of 14 and when he finished, he and his brothers started a business painting murals on walls and ceilings for mansions, public theatres and universities. -

Das Grillparzer-Denkmal Im Wiener Volksgarten“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Das Grillparzer-Denkmal im Wiener Volksgarten“ Verfasserin Mag. Rita Zeillinger angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 315 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Diplomstudium Kunstgeschichte Betreuerin Ao. Univ. – Prof. Dr. Ingeborg Schemper-Sparholz Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Motiv und Überlegungen zur Themenwahl .......................................................... 4 2 Forschungsstand ....................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Quellen ............................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Literatur .............................................................................................................. 7 3 Äußere Umstände ...................................................................................................... 9 3.1 Politische und gesellschaftliche Hintergründe ..................................................... 9 3.2 Beschluss der Denkmalerrichtung .....................................................................12 4 Das Denkmal und seine Verortung ...........................................................................22 4.1 Entstehung der Wiener Ringstraße ....................................................................22 4.2 Positionierung -

Download Download

Dreams anD sexuality A Psychoanalytical Reading of Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze benjamin flyThe This essay presenTs a philosophical and psychoanalyTical inTerpreTaTion of The work of The Viennese secession arTisT, GusTaV klimT. The manner of depicTion in klimT’s painTinGs underwenT a radical shifT around The Turn of The TwenTieTh cenTury, and The auThor attempTs To unVeil The inTernal and exTernal moTiVaTions ThaT may haVe prompTed and conTribuTed To This TransformaTion. drawinG from friedrich nieTzsche’s The BirTh of Tragedy as well as siGmund freud’s The inTerpreTaTion of dreams, The arTicle links klimT’s early work wiTh whaT may be referred To as The apollonian or consciousness, and his laTer work wiTh The dionysian or The subconscious. iT is Then arGued ThaT The BeeThoven frieze of 1902 could be undersTood as a “self-porTraiT” of The arTisT and used To examine The shifT in sTylisTic represenTaTion in klimT’s oeuVre. Proud Athena, armed and ready for battle with her aegis Pallas Athena (below), standing in stark contrast to both of and spear, cuts a striking image for the poster announcing these previous versions, takes their best characteristics the inaugural exhibition of the Vienna Secession. As the and bridges the gap between them: she is softly modeled goddess of wisdom, the polis, and the arts, she is a decid- but still retains some of the poster’s two-dimensionality (“a edly appropriate figurehead for an upstart group of diverse concept, not a concrete realization”2); the light in her eyes artists who succeeded in fighting back against the estab- speaks to an internal fire that more accurately represents lished institution of Vienna, a political coup if there ever the truth of the goddess; and perhaps most importantly, 28 was one. -

Gustav Klimt Vienna – Japan 1900 Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (23

Gustav Klimt Vienna – Japan 1900 Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (23. April – 10. Juli 2019) Toyota Municipal Museum of Art (23. Juli 2019 – 14. Oktober 2019) Gustav Klimt, Judith, 1901 Foto: Johannes Stoll © Belvedere, Wien Gustav Klimt. Wien und Japan 1900 Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, Japan 23. April bis 10. Juli 2019 Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, Japan 23. Juli bis 14. Oktober 2019 Das Belvedere präsentiert gemeinsam mit dem Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, dem Toyota Municipal Museum of Art und Japans führender Zeitung Asahi Shimbun die größte Klimt-Ausstellung in Japan seit Jahrzehnten. 115 Objekte, darunter zehn Klimt-Gemälde aus der Belvedere Sammlung und weitere prominente Werke aus aller Welt bereichern diese eindrucksvolle Schau, die anlässlich des Jubiläums 150 Jahre diplomatische Beziehungen zwischen Österreich und Japan gezeigt wird. „Gustav Klimt hat viele Stilmittel aus der japanischen Kunst und dem Kunsthandwerk übernommen und drückte damit seine Hochachtung vor dieser Kultur aus. Aus diesem Grund eignen sich seine Werke besonders gut für einen interkulturellen Austausch zwischen Österreich und Japan. In dieser umfassenden Ausstellung ist es gelungen, eine Zusammenstellung seiner Werke zu zeigen, wie sie in Japan noch nie zu sehen war“, so Stella Rollig, Generaldirektorin des Belvedere. Kuratiert und gestaltet hat die Ausstellung der Belvedere-Kurator Markus Fellinger, der sich inhaltlich auf zwei Schwerpunkte konzentriert: auf den Einfluss der Persönlichkeit des Künstlers in seinem Werk und auf die Bezüge zur japanischen Kunst. „Wie kaum ein anderer Künstler lässt Gustav Klimt durch sein Werk auf seine Persönlichkeit schließen, er weist sogar selbst darauf hin. Für mich war dies die Anregung dazu, den Spuren und Zeugnissen von Klimts Privat- und Seelenleben in seinen vielschichtigen und detailreichen Werken nachzuspüren“, so Markus Fellinger. -

KOLOMAN MOSER Ø KOLOMAN DESIGNING MODERN VIENNA Ø MOSER 1897–1907 Edited by Christian Witt-Dörring

5294-NG_MOSER_jacket_offset 19.03.13 13:47 Seite 1 MOSER KOLOMAN KOLOMAN MOSER ø KOLOMAN DESIGNING MODERN VIENNA ø MOSER 1897–1907 Edited by Christian Witt-Dörring With preface by Ronald S. Lauder, foreword by Renée Price, and contributions by Rainald Franz, Ernst Ploil, Elisabeth Schmuttermeier, Janis Staggs, Angela Völker, and Christian Witt-Dörring FRONT COVER: This catalogue accompanies an (TOP ROW) Armchair, ca. 1903, Neue Galerie DESIGNING New York; Easter egg, 1905, A.P. Collection, MODERN VIENNA exhibition at the Neue Galerie London; (MIDDLE ROW) Vase, 1905, New York and the Museum of A.P. Collection, London; Jewelry box, 1907, 1897–1907 Fine Arts, Houston, devoted to Private Collection; (BOTTOM ROW) Vase, 1903, Ernst Ploil, Vienna; Bread basket, 1910, Austrian artist and designer Asenbaum, London Koloman Moser (1868–1918). It BACK COVER: is the first museum retrospec- (TOP ROW) Centerpiece with handle, 1904, tive in the United States focused Private Collection; Coffer given by Gustav on Moser’s decorative arts. The Mahler to Alma Mahler, 1902, Private Collection; (MIDDLE ROW) Two napkin rings, exhibition is organized by Dr. 1904, Private Collection; Table, 1904, Private Christian Witt-Dörring, the Neue Collection; (BOTTOM ROW) Mustard pot, 1905, Private Collection; Display case for the Galerie Curator of Decorative Arts. Schwestern Flöge (Flöge Sisters) fashion salon, 1904, Private Collection The exhibition and catalogue survey the entirety of Moser’s decorative arts career. They ex- amine his early work as a graphic designer and his involvement with the Vienna Secession, with spe- cial focus given to his role as an PRESTEL PRESTEL artist for the journal Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring). -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Michael Steinbach Rare Books

Michael Steinbach Rare Books Freyung 6/4/6 – A – 1010 Vienna – Austria – Phone: +43-664-3575948 Mail: [email protected] – www.antiquariat-steinbach.com Books to be exhibited at the 51st California International Antiquarian Book Fair Pasadena Convention Center 330 E. Green St. Pasadena CA91101 - February 9-11 Please visit my booth 825 or order directly by email – Prices are net in €uros ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Alastair - Wilde, Oscar. The Sphinx. Illustrated and decorated by Alastair. London, John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1920. 31:23 cm. 10 tissue-garded plates, 2 plates before the endpapers, 13 decorated initials all in turquoise and black, by Alastair, 36 pages, Original cream cloth with gilt and turquoise illustration on front cover, gilt title on spine, top edge gilt, others untrimmed. 750, -- First Alastair edition, elaborately decorated with illustrations by Baron Hans-Henning von Voight (1887-1969), who published under the pseudonym of Alastair. One of 100 copies. - Spine very little rubbed, otherwise a fine copy. 2 Altenberg - Oppenheimer, Max. Peter Altenberg. Für die AKTION gezeichnet von Max Oppenheimer. Berlin, Die Aktion, o.J. 14,5 : 9,5 cm. 80, -- Zeit den Kopf Peter Altenbergs nach links mit seiner Signatur in Faksimile. - Werbepostkarte für die Zeitschrift 'Die Aktion'. Die Berliner Wochenzeitung DIE AKTION sei empfohlen, denn sie ist mutig ohne Literatengefecht, leidenschaftlich ohne Phrase und gebildet ohne Dünkel. (Franz Blei in 'Der lose Vogel'). 3 Andersen, Hans Christian. Zwölf mit der Post. Ein Neujahrsmärchen. Vienna Schroll (1919) 11 : 9,5 cm. With 12 coloured plates by Berthold Löffler. Illustrated original boards with coloured end-papers by B. -

Inspiration Beethoven

DE | EN 08.12.2020–05.04.2021 INSPIRATION BEETHOVEN EINE SYMPHONIE IN BILDERN AUS WIEN 1900 PRESSEBILDER | PRESS IMAGES 01 01 CASPAR VON ZUMBUSCH CASPAR VON ZUMBUSCH 1830–1915 1830–1915 Reduktion des Denkmals für Ludwig van Beethoven, 1877 Reduction of the memorial to Ludwig van Beethoven, 1877 Bronze, 53 × 24 × 27 cm Bronze, 53 × 24 × 27 cm Belvedere, Wien Belvedere, Vienna Foto: Belvedere, Wien Photo: Belvedere, Vienna 02 02 GUSTAV KLIMT GUSTAV KLIMT 1862–1918 1862–1918 Schubert am Klavier. Schubert at the Piano. Entwurf für den Musiksalon im Palais Dumba, 1896 Study for the music room in Palais Dumba, 1896 Öl auf Leinwand, 30 × 39 cm Oil on canvas, 30 × 39 cm Privatsammlung/Dauerleihgabe im Leopold Museum, Wien Private Collection/Permanent Loan, Leopold Museum, Vienna Foto: Leopold Museum, Wien/Manfred Thumberger Photo: Leopold Museum, Vienna/Manfred Thumberger 03 03 JOSEF MARIA AUCHENTALLER JOSEF MARIA AUCHENTALLER 1865–1949 1865–1949 Elfe am Bach. Für das Beethoven-Musikzimmer Elf at the Brook. For the Beethoven Music Room der Villa Scheid in Wien, 1898/99 of Villa Scheid in Vienna, 1898/99 Öl auf Leinwand, 176,5 × 88,3 cm Oil on canvas, 176,5 × 88,3 cm Andreas Maleta, aus der Victor & Martha Thonet Sammlung, Andreas Maleta, from the Victor & Martha Thonet Collection, Galerie punkt12, Wien gallery punkt12, Vienna Foto: amp, Andreas Maleta press & publication, Wien, 2020 Photo: amp, Andreas Maleta press & publication, Vienna, 2020 04 04 JOSEF MARIA AUCHENTALLER JOSEF MARIA AUCHENTALLER 1865–1949 1865–1949 Elfenreigen. Für das Beethoven-Musikzimmer -

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) Gustav Klimt's Work Is Highly Recognizable

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) Gustav Klimt’s work is highly recognizable around the world. He has a reputation as being one of the foremost painters of his time. He is regarded as one the leaders in the Viennese Secessionist movement. During his lifetime and up until the mid-twentieth century, Klimt’s work was not known outside the European art world. Gustav Klimt was born on July 14, 1862 in Baumgarten, near Vienna. He was the second child of seven born to a Bohemian engraver of gold and silver. His father’s profession must have rubbed off on his children. Klimt’s brother Georg became a goldsmith, his brother Ernst joined Gustav as a painter. At the age of 14, Klimt went to the School of Arts and Crafts at the Royal and Imperial Austrian Museum for Art and Industry in Vienna along with his brother. Klimt’s training was in applied art techniques like fresco painting, mosaics and the history of art and design. He did not have any formal painting training. Klimt, his brother Ernst and friend Franz Matsch earned a living creating architectural decorations on commission. They worked on villas and theaters and made money on the side by painting portraits. Klimt’s major break came when the trio helped their teacher paint murals in Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna. His work helped him begin gain the job of painting interior murals and ceilings in large public buildings on the Ringstraße, including a successful series of "Allegories and Emblems". His work on murals in the Burgtheater in Vienna earned him in 1888 a Golden order of Merit by Franz Josef I of Austria and he became an honorary member of the University of Munich and the University of Vienna. -

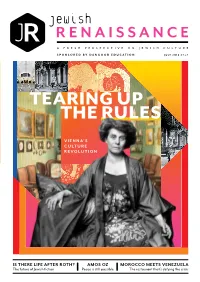

Tearing up the Rules

Jewish RENAISSANCE A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON JEWISH CULTURE SPONSORED BY DANGOOR EDUCATION JULY 2018 £7.25 TEARING UP THE RULES VIENNA’S CULTURE REVOLUTION IS THERE LIFE AFTER ROTH? AMOS OZ MOROCCO MEETS VENEZUELA The future of Jewish fiction Peace is still possible The restaurant that’s defying the crisis JR Pass on your love of Jewish culture for future generations Make a legacy to Jewish Renaissance ADD A LEGACY TO JR TO YOUR WILL WITH THIS SIMPLE FORM WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/CODICIL GO TO: WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/DONATIONS FOR INFORMATION ON ALL WAYS TO SUPPORT JR CHARITY NUMBER 1152871 JULY 2018 CONTENTS WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK JR YOUR SAY… Reader’s rants, raves 4 and views on the April issue of JR. WHAT’S NEW We announce the 6 winner of JR’s new arts award; Mike Witcombe asks: is there life after Roth? FEATURE Amos Oz on Israel at 10 70, the future of peace, and Trump’s controversial embassy move. FEATURE An art installation in 12 French Alsace is breathing new life into an old synagogue. NATALIA BRAND NATALIA © PASSPORT Vienna: The writers, 14 artists, musicians and thinkers who shaped modernism. Plus: we speak to the contemporary arts activists working in Vienna today. MUSIC Composer Na’ama Zisser tells Danielle Goldstein about her 30 CONTENTS opera, Mamzer Bastard. ART A new show explores the 1938 32 exhibition that brought the art the Nazis had banned to London. FILM Masha Shpolberg meets 14 34 the director of a 1968 film, which followed a group of Polish exiles as they found haven on a boat in Copenhagen. -

3. Theophil Hansen Und Das Parlament 9 3

MAGISTERARBEIT Titel der Magisterarbeit Der Mosaikfries von Eduard Lebiedzki, ausgeführt durch die Tiroler Glasmalerei und Mosaikanstalt, an der Fassade des Österreichischen Parlaments in Wien. Verfasserin Ilse Knoflacher angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. Phil) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 315 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Kunstgeschichte Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Lioba Theis Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung 3 2. Forschungsstand 4 2. 1. Theophil Hansen 5 2. 2. Eduard Lebiedzki und sein Mosaikfries 6 2. 3. Tiroler Glasmalerei und Mosaikanstalt in Innsbruck 7 2. 4. Mosaik 8 3. Theophil Hansen und das Parlament 9 3. 1. Hansens Jugend und Ausbildung in Kopenhagen 9 3. 2. Hansens Studien und erste Arbeiten in Athen 10 3. 3. Hansen erhält den Auftrag zur Errichtung des Parlaments 11 3. 4. Hansens Überlegungen zur Polychromie bzw. zum malerischen und bildhauerischen Schmuck des Parlaments 13 3. 5. Theophil Hansens Alter und Tod 18 4. Eduard Lebiedzki und der Mosaikfries 19 4. 1. Eduard Lebiedzkis Biographie 19 4. 2. Der Wettbewerb für den Fries, der Sieger Eduard Lebiedzki und die Entscheidung den Fries in Glasmosaik auszuführen 25 4. 3. Die Wiederentdeckung des Mosaiks 29 4. 4. Beschreibung der Tiroler Glasmalerei und Mosaikanstalt 35 4. 5. Entwurf und Erstellung der Kartons bis 1900 38 4. 6. Die Zusammenarbeit von Eduard Lebiedzki und der Tiroler Glasmalerei und Mosaikanstalt (Bestellbuch, Briefe…) 39 4. 7. Die Kosten 46 5. Der Mosaikfries 48 5. 1. Beschreibung des Frieses 48 5. 1. 1. Der Mittelteil 48 5. 1. 2. Die beiden Mosaiken an den Seitenwänden der Vorhalle 54 1 5. 1. 2. 1. Handel und Gewerbe 54 5.