What's Controlled About the Controlled Trial?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Wedlock by Wendy Moore Marry in Haste

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Wedlock by Wendy Moore Marry in haste . I n January 1777, newly widowed and once again wealthy, the young Countess of Strathmore found a proposal from a dying man impossible to resist. Andrew Robinson Stoney, romantically, was bleeding to death after fighting a duel to defend her honour. Apparently. Within days of the wedding, even the bride was questioning her reckless acceptance. Her new husband made an extraordinary recovery from wounds doctors swore were fatal. The "Captain" instantly embarked on a campaign of domestic terror. Wendy Moore's first book, The Knife Man, was a beautifully observed biography of the anatomising surgeon John Hunter. In Wedlock she offers an anatomy of an 18th-century upper-crust marriage. It was one that proved a travesty of the blossoming enlightenment ideal of loving companionship, but became a landmark case for women in the divorce courts. Stoney, an imposing Irish fortune-hunter, and the rich countess, Mary Eleanor Bowes, both used Hunter's services to deal in different ways with illegitimate babies. Each entered the prison of matrimony with something to hide. Mary's secrets were simple but significant: much of her enormous fortune was just out of reach. She had already signed a pre-nup to protect her existing offspring's future inheritance, and had recently racked up huge debts which now passed to her husband. Oh, and she was pregnant with another lover's child. Stoney's secrets were more devastating. He had managed to mask a truly vicious and calculating disposition. The duel was part of an elaborate trap to entice Mary into wedlock. -

The Linnean Society of London

NEWSLETTER AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON VOLUME 22 • NUMBER 4 • OCTOBER 2006 THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON Registered Charity Number 220509 Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BF Tel. (+44) (0)20 7434 4479; Fax: (+44) (0)20 7287 9364 e-mail: [email protected]; internet: www.linnean.org President Secretaries Council Professor David F Cutler BOTANICAL The Officers and Dr Sandy Knapp Dr Louise Allcock Vice-Presidents Prof John R Barnett Professor Richard M Bateman ZOOLOGICAL Prof Janet Browne Dr Jenny M Edmonds Dr Vaughan R Southgate Dr Joe Cain Prof Mark Seaward Prof Peter S Davis Dr Vaughan R Southgate EDITORIAL Mr Aljos Farjon Dr John R Edmondson Dr Michael F Fay Treasurer Dr Shahina Ghazanfar Professor Gren Ll Lucas OBE COLLECTIONS Dr D J Nicholas Hind Mrs Susan Gove Mr Alastair Land Executive Secretary Dr D Tim J Littlewood Mr Adrian Thomas OBE Librarian & Archivist Dr Keith N Maybury Miss Gina Douglas Dr George McGavin Head of Development Prof Mark Seaward Ms Elaine Shaughnessy Deputy Librarian Mrs Lynda Brooks Office/Facilities Manager Ms Victoria Smith Library Assistant Conservator Mr Matthew Derrick Ms Janet Ashdown Finance Officer Mr Priya Nithianandan THE LINNEAN Newsletter and Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London Edited by Brian G Gardiner Editorial .......................................................................................................................1 Society News............................................................................................................... 1 The -

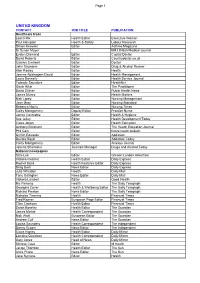

National Distribution Lists of Media for the "Help"

Page 1 UNITED KINGDOM CONTACT JOB TITLE PUBLICATION Healthcare trade Leona Rix Health Editor Executive Woman Paul Hampton Health & Safety Labour Research Simon Knowles Editor Asthma Magazine Dr Susan Mayer BMJ British Medical Journal Evelyn Diamond Editor Capital Doctor David Roberts Editor Countrydoctor.co.uk Charles Creswell Editor Doctor John Saunders Editor Drug & Alcohol Review Alan Radley Editor Health Joanna Abishegam-David Editor Health Management Laura Donnelly Editor Health Service Journal Yolande Saunders Editor HealthNet Gavin Atkin Editor The Practitioner David Gilliver Editor Public Health News James Munro Editor Health Matters Nick Lipley Editor Nursing Management Jean Gray Editor Nursing Standard Rebecca Norris Editor Nursing Times Caley Montgomery Deputy Editor Practice Nurse Janice Constable Editor Health & Hygiene Sue Jelley Editor Health Development Today Claire Jones Editor Health Education Anthony Blinkhorn Editor The Health Education Journal Phil Cain Editor future health bulletin Griffith Edwards Editor Addiction Deirdre Boyd Editor Addiction Today Caley Montgomery Editor Airways Journal Joanna Sharrocks Journals Manager Drugs and Alcohol Today National newspapers Sam Lee Editor Greater London Advertiser Victoria Fletcher Health Editor Daily Express Rachel Baird Health Features Editor Daily Express Greg Swift News Editor Daily Express Julie Wheldon Health Daily Mail Tony Gallagher News Editor Daily Mail Victoria Lambert Editor Good Health Nic Fleming Health The Daily Telegraph Georgina Cover Health & Wellbeing -

Mja News Spring 2014 2

The newsletter of the Medical Journalists’ Association Spring 2014 Thyme to enter the Summer Awards Following the positive feedback from all who attended this year’s Winter Awards the MJA will return to BMA House for our Summer Awards, highlight of the MJA year and, weather permitting, we should be able to enjoy the BMA Council’s herb garden and courtyard (see below). Philippa Pigache introduces the awards. ltogether, nine awards will be Government’s controversial, temporarily winning Digital innovation entry. presented on Wednesday, July 9 – ‘paused’ plan to collect and share patient invitations will reach your inbox data. These categories are open to all media: MJA Summer Awards are open to all. As in due course. Categories this year include film or sound broadcasts, print or online, always, they are free to members but, as in AEditor of a health or medical publication depending on the audience the material was earlier awards, we ask a small entry fee and entrants will be judged specifically in produced for. (£20) from non-members. This fee will be relation to the resources at their disposal, waived for anyone who applies to join the so that small publications are not disadvan - Entrants should submit a single item only MJA and pays an upfront subscription before taged by larger titles. We are also offering a for the Story of the year award and for submitting their entry. Full details of how Digital innovation award, where judges will Digital innovation. All other awards are for to pay will be included on the entry form. be looking for well-executed digital a body of work and entrants should submit products, which could include a data-rich up to three pieces of work (or publications) Timing info-graphic linked to a specific article, or via the online site linked to the MJA Launch: the MJA website awards section it could be a website redesign, smart-phone website, or in hard copy to a postal address.