Contract Law 162

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bench & Bar Games 2007

South China Sea MALAYSIA SINGAPORE MALAYSIA | SINGAPORE Bench & Bar Games 2007 28 - 30 April 2007 Java Sea OFFICES SINGAPORE 80 RAFFLES PLACE #33-00 UOB PLAZA 1 SINGAPORE 048624 TEL: +65 6225 2626 FAX: +65 6225 1838 SHANGHAI UNIT 23-09 OCEAN TOWERS NO. 550 YAN AN EAST ROAD SHANGHAI 200001, CHINA TEL: +86 (21) 6322 9191 FAX: +86 (21) 6322 4550 EMAIL [email protected] CONTACT PERSON HELEN YEO, MANAGING PARTNER YEAR ESTABLISHED 1861 NUMBER OF LAWYERS 95 KEY PRACTICE AREAS CORPORATE FINANCE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY & TECHNOLOGY LITIGATION & ARBITRATION REAL ESTATE LANGUAGES SPOKEN ENGLISH, MANDARIN, MALAY, TAMIL www.rodyk.com 1 Contents Message from The Honourable The Chief 2 10 Council Members of Bar Council Malaysia Justice, Singapore 2007/2008 Message from The Honourable Chief 3 15 Sports Committee - Singapore and Malaysia Justice, Malaysia Message from the President of The Law 4 16 Teams Society of Singapore Message from the President of Bar Council 5 Malaysia 22 Results of Past Games 1969 to 2006 Message from Chairman, Sports 6 Sports Suit No. 1 of 1969 Committee, The Law Society of Singapore 23 Message from Chairman, Sports 7 Acknowledgements Committee, Bar Council Malaysia 24 9 The Council of The Law Society of Singapore 2007 Malaysia | Singapore Bench & Bar Games 2007 022 Message from The Honourable The Chief Justice, Singapore The time of the year has arrived once again for the Malaysia/Singapore Bench & Bar Games. Last year we enjoyed the warm hospitality of our Malaysian hosts on the magical island of Langkawi and this year, we will do all that we can to reciprocate. -

Supreme Court of Singapore

SUPREME COURT OF SINGAPORE 2012ANNUAL REPORT VISION To establish and maintain a world-class Judiciary. MISSION To superintend the administration of justice. VALUES Integrity and Independence Public trust and confidence in the Supreme Court rests on its integrity and the transparency of its processes. The public must be assured that court decisions are fair and independent, court staff are incorruptible, and court records are accurate. Quality Public Service As a public institution dedicated to the administration of justice, the Supreme Court seeks to tailor its processes to meet the needs of court users, with an emphasis on accessibility, quality and the timely delivery of services. Learning and Innovation The Supreme Court recognises that to be a world-class Judiciary, we need to continually improve ourselves and our processes. We therefore encourage learning and innovation to take the Supreme Court to the highest levels of performance. Ownership We value the contributions of our staff, who are committed and proud to be part of the Supreme Court. SUPREME COURT ANNUAL REPORT 2012 01 Contents 02 46 MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF JUSTICE STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT • Launch of eLitigation 14 • Launch of the Centralised Display CONSTITUTION AND JURISDICTION Management System (CDMS) • Supreme Court Staff Workplan 18 Seminar SIGNIFICANT EVENTS • Legal Colloquium • Opening of the Legal Year • Organisational Accolades • 2nd Joint Judicial Conference • Mass Call 52 • Launch of The Learning Court TIMELINESS OF JUSTICE • Legal Assistance Scheme for • Workload -

Chan Sek Keong the Accidental Lawyer

December 2012 ISSN: 0219-6441 Chan Sek Keong The Accidental Lawyer Against All Odds Interview with Nicholas Aw Be The Change Sustainable Development from Scraps THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE FACULTY OF LAW Contents DEAN’S MESSAGE A law school, more so than most professional schools at a university, is people. We have no laboratories; our research does not depend on expensive equipment. In our classes we use our share of information technology, but the primary means of instruction is the interaction between individuals. This includes teacher and student interaction, of course, but as we expand our project- based and clinical education programmes, it also includes student-student and student-client interactions. 03 Message From The Dean MESSAGE FROM The reputation of a law school depends, almost entirely, on the reputation of its people — its faculty LAW SCHOOL HIGHLIGHTS THE DEAN and staff, its students, and its alumni — and their 05 Benefactors impact on the world. 06 Class Action As a result of the efforts of all these people, NUS 07 NUS Law in the World’s Top Ten Schools Law has risen through the ranks of our peer law 08 NUS Law Establishes Centre for Asian Legal Studies schools to consolidate our reputation as Asia’s leading law school, ranked by London’s QS Rankings as the 10 th p12 09 Asian Law Institute Conference 10 NUS Law Alumni Mentor Programme best in the world. 11 Scholarships in Honour of Singapore’s First CJ Let me share with you just a few examples of some of the achievements this year by our faculty, our a LAWMNUS FEATURES students, and our alumni. -

Protection from Harassment Act 2014: Offences and Remedies Man YIP Singapore Management University, [email protected]

Singapore Management University Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Research Collection School Of Law School of Law 1-2015 Protection from harassment act 2014: Offences and remedies Man YIP Singapore Management University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research Part of the Law and Society Commons Citation YIP, Man. Protection from harassment act 2014: Offences and remedies. (2015). Research Collection School Of Law. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research/2845 This Blog Post is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Collection School Of Law by an authorized administrator of Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email [email protected]. 6 January 2015 Opening of Legal Year 2015: A Year for Pushing Boundaries 5 January 2015 marked the Opening of the Legal Year 2015. From the speeches made by the Attorney-General, the President of the Law Society, and the Chief Justice, the 50th year of Singapore’s independence is going to be a glorious year of pushing boundaries. In his speech, Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon outlined numerous events and developments that Singapore’s legal community can look forward to. Indeed, several events will be of great interest to the international legal community. In a nutshell, the theme for 2015 is about strengthening the administration of justice in two dimensions. The internationalist dimension is to consolidate Singapore’s position as the regional and international dispute resolution hub for commercial matters through, in particular, the establishment of the Singapore International Commercial Court (“SICC”), which was also launched at the Opening of Legal Year 2015. -

The One Judiciary Annual Report 2018

CHIEF JUSTICE’S FOREWORD As I have said on previous occasions, the Judiciary The Courts have also launched several initiatives is the custodian of the sacred trust to uphold to help members of the public better navigate our the rule of law. To this end, it must not only hand judicial system. In October 2018, the State Courts, down judgments which are fair and well-reasoned, together with community partners, launched the but also ensure that justice is accessible to all, first part of a Witness Orientation Toolkit to help for it is only by so doing that it can command the prepare vulnerable witnesses for their attendance trust, respect and confidence of the public. This in court. Similarly, the Family Justice Courts worked is indispensable to the proper administration of closely with the Family Bar to publish, earlier this justice. January, the second edition of The Art of Family Lawyering, which is an e-book that hopes to This One Judiciary Annual Report will provide an encourage family lawyers to conduct proceedings overview of the work done by the Supreme Court, in a manner that reduces acrimony between the the State Courts and the Family Justice Courts in parties, focuses on the best interests of the child, 2018 to enhance our justice system to ensure that it and conduces towards the search for meaningful continues to serve the needs of our people. long-term solutions for families. On the international front, we continued to expand our international networks. Regionally, we Strengthening Our Justice System Both the international legal infrastructure to promote law schools and to expand the opportunities that deepened our engagement with ASEAN by playing Within and Without cross-border investment and trade. -

Lim Leong Huat V Chip Hup Hup Kee Construction Pte Ltd and Another

Lim Leong Huat v Chip Hup Hup Kee Construction Pte Ltd and another [2010] SGHC 170 Case Number : Suit No 779 of 2006 Decision Date : 08 June 2010 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Quentin Loh J Counsel Name(s) : Randolph Khoo, Johnson Loo and Chew Ching Li (Drew & Napier LLC) for the plaintiff (by original action) and the first, second and third defendants (by counterclaim); Molly Lim SC, Philip Ling and Hwa Hoong Luan (Wong Tan & Molly Lim LLC) for the first and second defendants (by original action) and the plaintiff (by counterclaim). Parties : Lim Leong Huat — Chip Hup Hup Kee Construction Pte Ltd and another Tort Restitution 8 June 2010 Judgment reserved. Quentin Loh J: Introduction 1 “A falling out of thieves” is an apt description of this case. For 6 weeks I heard the evidence unfold: of non-existent employees (euphemistically called “Proxies”) comprising real persons complete with identity card numbers and Central Provident Fund (“CPF”) accounts, of utilising these falsified local employees to mislead the Ministry of Manpower (“MOM”) into allotting higher foreign worker entitlements, of levying “commissions” on foreign workers from China, of fictitious invoices to build up a track record of “profit” for possible listing, of withdrawals of large sums of money from another euphemistically styled “Salary Accruals” account which enabled the directors not only to withdraw large sums of money as reimbursement of non-existent “expenses” but also to evade tax, of fictitious payments to non-existent subcontractors, of questionable loans (some of which were in the hundreds of thousands) to the company, and also of other loans which were made on one day and withdrawn or repaid on the next. -

YRF Annual Report 2019

Your support makes a difference. Come join us on this journey of empowering and transforming the lives of our beneficiaries today. Transformative Change Yellow Ribbon Fund Secretariat Prisons HQ 980 Upper Changi Road North with Collective E ffort Blk B, Level 2, Singapore 507708 For more information, please go to our website: www.yellowribbon.gov.sg Yellow Ribbon Fund Annual Report 2019 Contents Chairman’s Message 01-02 Events & Activities 19-22 Transformative Corporate Profile 03-04 Collaborations 23-25 with Partners Year in Numbers 05-06 Governance 26-42 Board Governance 27-30 Governance Evaluation Checklist 31-32 All of us play a part to effect transformative change. Empowering Lives 07-12 Committees 33-39 Beyond giving a chance for ex-offenders and inmates to rebuild Through Education Main Committee 33-34 their lives and that of their families, every contribution from the Skills Training Assistance to Restart 09-10 Advancement Committee 35 society has enhanced their abilities to reintegrate back to the (STAR) Bursary Beneficiary – Mr Rayyan Yusof Audit Committee 36 society as contributing citizens. In turn, our beneficiaries are Skills Training Assistance to Restart 11-12 Family & Children’s 37 empowered to give back and pay it forward to our community in (STAR) Bursary Beneficiary – Welfare Committee their own time. Mr Arnold Teo Fund Allocation Committee 38 STAR Bursary Committee 39 Yellow Ribbon Fund with its partners, donors and the community at large have come together collectively, to make sustainable Financial Statement 40-42 impact which help shapes a more compassionate and Preventing 13-18 Statement of Financial Position 40 Intergenerational Statement of Financial Activities 41-42 inclusive society. -

SAL Annual Report 2001

SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW ANNUAL REPORT Financial year 2001/2002 MISSION STATEMENT Building up the intellectual capital, capability and infrastructure of members of the Singapore Academy of Law. Promotion of esprit de corps among members of the Singapore Academy of Law. SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW ANNUAL REPORT 1 April 2001 - 31 march 2002 5Foreword 7Introduction 13 Annual Report 2001/2002 43 Highlights of the Year 47 Annual Accounts 2001/2002 55 Thanking the Fraternity Located in City Hall, the Singapore Academy of Law is a body which brings together the legal profession in Singapore. FOReWoRD SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW FOREWORD by Chief Justice Yong Pung How President, Singapore Academy of Law From a membership body in 1988 with a staff strength of less than ten, the Singapore Academy of Law has grown to become an internationally-recognised organisation serving many functions and having two subsidiary companies – the Singapore Mediation Centre and the Singapore International Arbitration Centre. The year 2001/2002 was a fruitful one for the Academy and its subsidiaries. The year kicked off with an immersion programme in Information Technology Law for our members. The inaugural issue of the Singapore Academy of Law Annual Review of Singapore Cases 2000 was published, followed soon after by the publication of a book, “Developments in Singapore Law between 1996 and 2000”. The Singapore International Arbitration Centre launched its Domestic Arbitration Rules in May 2001, and together with the Singapore Mediation Centre, launched the Singapore Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy for resolving “.sg” domain name disputes. The Academy created a Legal Development Fund of $5 million to be spread over 5 years for the development of the profession in new areas of law and practice. -

Opening of the Legal Year 2018 Speech by the President of the Law

Opening of the Legal Year 2018 Speech by the President of the Law Society INTRODUCTION 1. May it please Your Honours, Chief Justice, Judges of Appeal, Judges and Judicial Commissioners. WELCOME 2. First, let me extend a warm welcome to our overseas Bar leaders hailing from Australia, Brunei, China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Myanmar and Taiwan. LAWASIA President Christopher Leong and Inter-Pacific Bar Association Vice President, Mr Francis Xavier SC are also special guests in this ceremony. 3. 2017 heralded significant developments in judicial offices in the Supreme Court :- a. Retirement of Justice Chao Hick Tin as a Judge of Appeal on 27 September 2017 marked by an unforgettable Valedictory Reference convened by the Supreme Court. We were pleased to read recently about Justice Chao’s appointment as Senior Judge for three years with effect from 5 January 2018. b. Appointment of Judge of Appeal Andrew Phang as Vice President of the Court of Appeal following his predecessor Justice Chao’s retirement. c. Appointment of Justice Steven Chong as Judge of Appeal. d. Appointment of then Deputy AG Tan Siong Thye and then Judicial Commissioners Chua Lee Ming, Kannan Ramesh, Aedit Abdullah, Valerie Thean, Debbie Ong and Hoo Sheau Peng as Judges of the Supreme Court. 4. Last week, Senior Judges Chan Sek Keong and Kan Ting Chiu retired; marking an end to their stellar and distinguished service on the Bench. Justices Andrew Ang, Tan Lee Meng and Lai Siu Chiu were reappointed as Senior Judges effective last Friday. 5. The Bar is certain that the new judicial appointees will leave their own individual, indelible imprint on Singapore jurisprudence. -

1 Response by Chief Justice Sundaresh

RESPONSE BY CHIEF JUSTICE SUNDARESH MENON OPENING OF THE LEGAL YEAR 2018 Monday, 8 January 2018 Mr Attorney, Mr Vijayendran, Members of the Bar, Honoured Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen: I. Introduction 1. It is my pleasure to welcome you all to the Opening of this Legal Year. I particularly wish to thank the Honourable Chief Justice Prof Dr M Hatta Ali and Justice Takdir Rahmadi of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Indonesia, the Right Honourable Tun Md Raus Sharif, Chief Justice of Malaysia, and our other guests from abroad, who have made the effort to travel here to be with us this morning. II. Felicitations 2. 2017 was a year when we consolidated the ongoing development of the Supreme Court Bench, and I shall begin my response with a brief recap of the major changes, most of which have been alluded to. 1 A. Court of Appeal 3. Justice Steven Chong was appointed as a Judge of Appeal on 1 April 2017. This was in anticipation of Justice Chao Hick Tin’s retirement on 27 September 2017, after five illustrious decades in the public service. In the same context, Justice Andrew Phang was appointed Vice-President of the Court of Appeal. While we will feel the void left by Justice Chao’s retirement, I am heartened that we have in place a strong team of judges to lead us forward; and delighted that Justice Chao will continue contributing to the work of the Supreme Court, following his appointment, a few days ago, as a Senior Judge. 4. At the same time, we bid farewell to Senior Judge Chan Sek Keong. -

SAL Annual Report 2010

CONTENTS Singapore PRESIDENT’S REVIEW 2 SENATE 4 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 6 Academy of Law FACT, FIGURES & HIGHLIGHTS 10 LEGAL KNOWLEDGE 12 Annual Report 2010/11 LEGAL INDUSTRY 16 LEGAL TECHNOLOGY 22 CORPORATE SERVICES 26 FINANCIAL REVIEW 30 EDITORIAL TEAM Editors • Ms Serene Wee Chief Executive • Ms Foo Kim Leng Assistant Director, Corporate Communications & Events Management • Ms Serene Ong Assistant Manager, Corporate Communications & Events Management Art Direction MAKE Contributors legal knowledge • Mr Bala Shunmugam Director, Academy Publishing • Ms Grace Lee-Kok Assistant Director, Legal Education • Ms Melissa Goh RA SING Consultant, Law Reform legal industry • Mr Loong Seng Onn Senior Director, Legal Industry Cluster legal technology STANDARDS • Ms Tay Bee Lian Senior Director, LawNet of Legal Practice corporate services • Ms Low Hui Min Chief Financial Officer, Stakeholding, Finance & Investment • Ms Lai Wai Leng MICA (P) 122/11/2011, ISSN 1793-5679 Assistant Director, Finance & Membership • Ms Teo Lay Eng Senior Manager, Human Resource & Administration CONTENTS ABOUT US PRESIDENT’S REVIEW 2 SENATE 4 The Singapore Academy of Law EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 6 (the “Academy”) has close to 9,000 FACT, FIGURES & HIGHLIGHTS 10 members comprising all persons LEGAL KNOWLEDGE 12 who are called as advocates and LEGAL INDUSTRY 16 solicitors of the Supreme Court LEGAL TECHNOLOGY 22 or who are appointed as Legal CORPORATE SERVICES 26 30 Service Officers. The membership FINANCIAL REVIEW of the Academy comprises of the Bench, the Bar, and large numbers EDITORIAL TEAM of corporate counsel and faculty members of the local law schools. Editors • Ms Serene Wee The Academy is governed by the Senate which is headed by the Chief Executive • Ms Foo Kim Leng Honourable the Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong as President. -

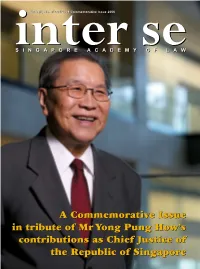

A Commemorative Issue in Tribute of Mr Yong Pung How's Contributions As Chief Justice of the Republic of Singapore a Commemora

MICA (P) No. 076/05/2006 Commemorative Issue 2006 interinterSINGAPORESINGAPORE ACADEMYACADEMY se seOFOF LAWLAW AA CommemorativeCommemorative IssueIssue inin tributetribute ofof MrMr YongYong PungPung How’sHow’s contributionscontributions asas ChiefChief JusticeJustice ofof thethe RepublicRepublic ofof SingaporeSingapore 18 The Legal Service 20 The Academy 07 Speeches 24 Well-Wishes 10 The Judgments Contents Commemorative Issue 2006 01 Inter Alia 18 The Legal Service O u r d i r e c t o r p a y s t r i b u t e t o t h e Chief Justice Yong’s commitment to leadership of Chief Justice Yong raising standards in the Legal Service 03 Letters 20 The Academy Words of thanks to Chief Justice Yong The achievements of the Singapore from the Prime Minister and Minister Academy of Law under the leadership Mentor of Chief Justice Yong 07 Speeches 24 Well-Wishes Speeches of tribute and thanks from Words of thanks, appreciation and the President and Chief Justice Yong admiration for Chief Justice Yong from at a farewell dinner hosted in Chief at home and abroad Justice Yong’s honour at the Istana [Cover]: Image of Chief Justice Yong Pung How 10 The Judgments reproduced with the kind permission of the Supreme An overview of some of the important Court Corporate Communications Section. law made by Chief Justice Yong [Speeches]: Images from MICA Photo Unit reproduced with the kind permission of the Istana. 14 The Courts [The Judgments and The Courts]: Images reproduced Chief Justice Yong’s comprehensive with the kind permission of the Supreme Court reforms of the Singapore courts system Corporate Communications Section.