West Cork Resource Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Design and Construction of New Mizen Head Footbridge

The Design and Construction of New Mizen Head Footbridge Murt Coleman, BE CEng FIEI, Chartered Engineer Managing Director, Carillion Irishenco Ltd. Enda Collery, BA BAI CEng MIEI, Chartered Engineer Contracts Manager, Carillion Irishenco Ltd. Eoghan Lehane, BE Eur Ing CEng MIEI MCIWEM, Chartered Engineer Civil Engineering and Property Manager, Commissioners of Irish Lights Brendan Minihane, BE Eur Ing CEng MIEI, Chartered Engineer Project Resident Engineer, Cork County Council Ross O’Donovan, Dip Eng BEng CEng MIEI, Chartered Engineer Senior Resident Engineer, RPS Consulting Engineers Ltd. Noel O’Keeffe, BE Eur Ing CEng FIEI MICE, Chartered Engineer County Engineer, Cork County Council Kevin Power, BE CEng FIEI MICE MCIWEM, Chartered Engineer Director, RPS Consulting Engineers Ltd. Kieran Ruane*, BE MSc(Eng) CEng MIStructE MIEI MICE, Chartered Engineer Technical Director, RPS Consulting Engineers Ltd. Paper first presented to a joint meeting of Engineers Ireland, Institution of Structural Engineers and The Irish Concrete Society in Cork on 08.03.2011. *Corresponding author: Tel +353 (0) 21 4665900, [email protected]. Design and Construction of New Mizen Head Footbridge Paper first presented to Engineers Ireland, IStructE and ICS in Cork on 08.03.2011 The Design and Construction of New Mizen Head Footbridge Overview On the 18th of October 1907, sanction was given for the erection of a reinforced concrete Mizen Head Footbridge in County Cork is a bridge to give access to the island. reinforced concrete through-arch structure Construction of the bridge commenced in 1908 spanning 50m. The original structure was and was completed in 1909. The Contractor completed in 1909. -

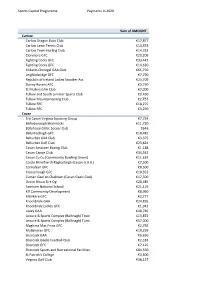

Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Sum of AMOUNT Carlow

Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Sum of AMOUNT Carlow Carlow Dragon Boat Club €17,877 Carlow Lawn Tennis Club €14,353 Carlow Town Hurling Club €14,332 Clonmore GFC €23,209 Fighting Cocks GFC €33,442 Fighting Cocks GFC €14,620 Kildavin Clonegal GAA Club €61,750 Leighlinbridge GFC €7,790 Republic of Ireland Ladies Snooker Ass €23,709 Slaney Rovers AFC €3,750 St Mullins GAA Club €7,000 Tullow and South Leinster Sports Club €9,430 Tullow Mountaineering Club €2,757 Tullow RFC €18,275 Tullow RFC €3,250 Cavan 3rd Cavan Virginia Scouting Group €7,754 Bailieborough Shamrocks €11,720 Ballyhaise Celtic Soccer Club €646 Ballymachugh GFC €10,481 Belturbet GAA Club €3,375 Belturbet Golf Club €23,824 Cavan Amatuer Boxing Club €1,188 Cavan Canoe Club €34,542 Cavan Co Co (Community Bowling Green) €11,624 Coiste Bhreifne Uí Raghaillaigh (Cavan G.A.A.) €7,500 Cornafean GFC €8,500 Crosserlough GFC €10,352 Cuman Gael an Chabhain (Cavan Gaels GAA) €17,500 Droim Dhuin Eire Og €20,485 Farnham National School €21,119 Kill Community Development €8,960 Killinkere GFC €2,777 Knockbride GAA €24,835 Knockbride Ladies GFC €1,942 Lavey GAA €48,785 Leisure & Sports Complex (Ballinagh) Trust €13,872 Leisure & Sports Complex (Ballinagh) Turst €57,000 Maghera Mac Finns GFC €2,792 Mullahoran GFC €10,259 Shercock GAA €6,650 Shercock Gaelic Football Club €2,183 Shercock GFC €7,125 Shercock Sports and Recreational Facilities €84,550 St Patrick's College €3,500 Virginia Golf Club €38,127 Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Virginia Kayak Club €9,633 Cavan Castlerahan -

15Th September

7 NIGHTS IN LISBON INCLUDINGWIN! FLIGHTS 2019 6th - 15th September www.atasteofwestcork.com Best Wild Atlantic Way Tourism Experience 2019 – Irish Tourism & Travel Industry Awards 1 Seaview House Hotel & Bath House Seaview House Hotel & Bath House Ballylickey, Bantry. Tel 027 50073 Join us for Dinner served nightly or Sunday [email protected] House in Hotel our Restaurant. & Bath House Perfect for Beara & Sheep’s Head walkingAfternoon or aHigh trip Tea to theor AfternoonIslands Sea served on Saturday by reservation. September 26th – 29th 2019 4 Star Country Manor House Enjoy an Organic Seaweed Hotel, set in mature gardens. Enjoy an Organic Seaweed Bath in one IARLA Ó LIONÁIRD, ANTHONY KEARNS, ELEANOR of Bathour Bath in one Suites, of our or Bath a Treatment Suites, in the Highly acclaimed by ornewly a Treatment developed in the Bath newly House. SHANLEY, THE LOST BROTHERS, YE VAGABONDS, Michelin & Good Hotel developed Bath House with hand Guides as one of Ireland’s top 4**** Manor House Hotel- Ideal for Small Intimate Weddings, JACK O’ROURKE, THOMAS MCCARTHY. craftedSpecial woodburning Events, Private Dining outdoor and Afternoon Tea. destinations to stay and dine saunaSet within and four ac rhotes of beaut tub;iful lya manicu perfectred and mature gardens set 4**** Manor House Hotel- Ideal for Small Intimate Weddings, back from the Sea. Seaview House Hotel is West Cork’s finest multi & 100 best in Ireland. recoverySpecial followingEvents, Private Diningactivities and Afternoon such Tea. award winning Country Manor Escape. This is a perfect location for discovering some of the worlds most spectacular scenery along the Wild ****************** Set withinas four walking acres of beaut andifully manicu cycling.red and mature gardens set Atlantic Way. -

BMH.WS1234.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,234 Witness Jack Hennessy, Knockaneady Cottage, Ballineen, Co. Cork. Identity. Adjutant Ballineen Company Irish Vol's. Co. Cork; Section Leader Brigade Column. Subject. Irish Volunteers, Ballineen, Co. Cork, 1917-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.2532 Form BSM2 STATEMENT BY JOHN HENNESSY, Ballineen, Co. Cork. I joined the Irish Volunteers at Kilmurry under Company Captain Patrick O'Leary in 1917. I remained with that company until 1918 when I moved to Ballineen, where I joined the local company under Company Captain Timothy Francis. Warren. Shortly after joining the company I was appointed Company Adjutant. During 1918 and the early days of 1919 the company was. being trained and in 1918 we had preparations made. to resist conscription. I attended meetings of the Battalion Council (Dunmanway Battalion) along with the Company Captain. The Battalion Council discussed the organisation and training in each company area. In May, 1919, the Ballineen Company destroyed Kenniegh R.I.C. barracks. which had been vacated by the garrison.. Orders were issued by the brigade through each battalion that the local R.I.C. garrison was to be boycotted by all persons in the area. This order applied to traders, who were requested to stop supplying the R.I.C. All the traders obeyed the order, with the exception of one firm, Alfred Cotters, Ballineen, who continued to supply the R.I.C. with bread. The whole family were anti-Irish and the R.I.C. -

United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE

THE CHURCH OF IRELAND United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE A Symbol of ‘Hope’ May 2020 €2.50 w flowers for all occasions w Individually w . e Designed Bouquets l e g a & Arrangements n c e f lo Callsave: ri st 1850 369369 s. co m The European Federation of Interior Landscape Groups •Fresh & w w Artificial Plant Displays w .f lo •Offices • Hotels ra ld •Restaurants • Showrooms e c o r lt •Maintenance Service d . c •Purchase or Rental terms o m Tel: (021) 429 2944 bringing interiors alive 16556 DOUGLAS ROAD, CORK United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross DIOCESAN MAGAZINE May 2020 Volume XLV - No.5 The Bishop writes… Dear Friends, Last month’s letter which I published online was written the day after An Taoiseach announced that gatherings were to be limited to 100 people indoors and to 500 people outdoors. Since then we have had a whirlwind of change. Many have faced disappointments and great challenges. Still others find that the normality of their lives has been upended. For too many, illness they have already been living with has been complicated, and great numbers have struggled with or are suffering from COVID-19. We have not been able to give loved ones who have died in these times the funerals we would like to have arranged for them. Those working in what have been classed as ‘essential services’, especially those in all branches of healthcare, are working in a new normality that is at the limit of human endurance. Most of us are being asked to make our contribution by heeding the message: ‘Stay at home’ These are traumatic times for everyone. -

Mizen Guided Tour 310505

History of Mizen Head Signal Station 1810 Only three lights on the southwest coast – Loop Head, Clear Island and the Old Head of Kinsale. 1826 2 lighthouses were erected on the Great Skellig 1847 SS Stephen Whitney, a 1034 tonnes liner, went down off Cape Clear with the loss of 100 lives and it was decided to build a lighthouse on the Fastnet or Fastness Rock as Cape Clear lighthouse was too far inland 1848 – 53 the Corporation of the Port of Dublin built a cast iron 63’ tower on the Fastnet at an estimated cost of £20,000. 1854 The Fastnet Rock Lighthouse was commissioned. The seas around the Fastnet were so strong that the structure needed constant strengthening and the costs soared to £27000. 1867 The ‘Dublin Port Act’ transferred the lighthouse powers to the Commissioners of Irish Lights. 1876 More repairs were carried out at the Fastnet Light 1881 Calf Rock (off Dursey Island) Lighthouse which was a similar construction to the Fastnet was carried away in a gale. The same gale broke the glass in the Fastnet lantern 148’ above sea level. 1883 The Fastnet was equipped with an explosive fog signal 1891 The Irish Lights Board decided that the Fastnet light was not powerful enough and proposed a 147’ granite tower to house a biform oil light. 1899-1903 The building of the Fastnet lighthouse at a cost of £84,000. 1905 There was a demand from ship owners, who fund the Lighthouse Service through harbour dues, that there should be a lighthouse at Mizen Head. -

Sea Environmental Report the Three

SEA ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT FOR THE THREE PENINSULAS WEST CORK AND KERRY DRAFT VISITOR EXPERIENCE DEVELOPMENT PLAN for: Fáilte Ireland 88-95 Amiens Street Dublin 1 by: CAAS Ltd. 1st Floor 24-26 Ormond Quay Upper Dublin 7 AUGUST 2020 SEA Environmental Report for The Three Peninsulas West Cork and Kerry Draft Visitor Experience Development Plan Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................v Glossary ..................................................................................................................vii SEA Introduction and Background ..................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction and Terms of Reference ........................................................................... 1 1.2 SEA Definition ............................................................................................................ 1 1.3 SEA Directive and its transposition into Irish Law .......................................................... 1 1.4 Implications for the Plan ............................................................................................. 1 The Draft Plan .................................................................................... 3 2.1 Overview ................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Relationship with other relevant Plans and Programmes ................................................ 4 SEA Methodology .............................................................................. -

Planning Applications

CORK COUNTY COUNCIL Page No: 1 PLANNING APPLICATIONS PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED FROM 11/01/2020 TO 17/01/2020 in deciding a planning application the planning authority, in accordance with section 34(3) of the Act, has had regard to submissions or observations recieved in accordance with these Regulations; that it is the responsibility of any person wishing to use the personal data on planning applications and decisions lists for direct marketing purposes to be satisfied that they may do so legitimately under the requirements of the Data Protection Acts 1988 and 2003 taking into account of the preferences outlined by applicants in their application FUNCTIONAL AREA: West Cork, Bandon/Kinsale, Blarney/Macroom, Ballincollig/Carrigaline, Kanturk/Mallow, Fermoy, Cobh, East Cork FILE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME APP. TYPE DATE RECEIVED DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION M.O. DATE M.O. NUMBER 19/00303 Deirdre McCarthy Permission for 08/05/2019 Permission for the following works to a protected structure: 14/01/2020 16 Retention retention of change of use of ground floor unit from retail use to office use The Round Tower Main Street & Barrack Street, Townlots Bantry, Co. Cork 19/00554 Connolly Property Developments Permission 23/08/2019 Construct a dwelling house along with all associated site works on 17/01/2020 20 serviced site Site No. 7 Cove View Baltimore Co. Cork 19/00555 Connolly Property Developments Permission 26/08/2019 To construct dwelling house along with all associated site works on 17/01/2020 21 serviced site Site No. 2 Cove View Baltimore Co. Cork 19/00662 Aiden McCarthy Permission 11/10/2019 Permission is being sought for the following works to existing 14/01/2020 13 dwelling house and attached ruinous outbuilding; (i) demolition of existing single storey annex to rear of house, (ii) construction of new two storey extension to rear, (iii) renovations to existing house including installation of 4 no. -

Clonakilty Lodge in Co. Cork

Clonakilty Lodge in Co. SLIGO Cork OFFALY Clonakilty Lodge Accommodation Centre is located in Clonakilty in County Cork which is in the south-west of Ireland. The centre houses families. COUNTY CORK Centre Manager: Michael Plichta Public Health Nurse: Anne Marie Hegarty Community Welfare Officer: Mary O’Mahony Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland LOCAL SERVICES PUBLIC SERVICES Social Welfare Citizen’s Information Service Unit 2, Supervalu Shopping Centre, 80 South Mall, Cork City Faxbridge, Clonakilty, Co. Cork Email: [email protected] Phone: 0238821210 Free legal advice available first and third Clonakilty Garda Station Wednesday of every month 18.30 – 19.30 McCurtain Hill, Scartagh, Clonakilty, Co. Cork Phone: 023 882 1570 VOLUNTEERING AND EDUCATION Cork Volunteer Centre Clonakilty College of Further Education 13 North Main Street, Cork City Western Road, Clonakilty, Co. Cork Phone: 0214251572 Phone: 023-8833877 Cork City Adult Guidance Service Email: [email protected] 22 South Mall, Cork City Clonakilty Library Phone: 0214907149 Kent St, Maulnaskehy, Clonakilty, Co. Cork Welcome English Language Centre Phone: 023 883 4275 Free English lessons in Cork City. Phone: 0872281584 / 0214316537 SUPPORT GROUPS Nasc, Irish Immigrant Support LINC (LBGT Women) Centre 11A White Street, Cork City Website: www.nascireland.org www.linc.ie Phone: 0214503462 Phone: 0214808600 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] UP Cork LGBT Service (Ages 15-24) The Cork Migrant Centre 4 South Terrace, Cork 14 George’s Quay, Cork City Phone: 0214399862 Phone: 0868246087 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Cork Gay Project (Men) Clonakilty Friends of Asylum Seekers 4 South Terrace, Cork City https://www.facebook.com/ClonFOAS/ Website: www.corkgayproject.com National LGBT Support Line Phone: 0214300430 1890 929 539 Email: [email protected] CHILD AND FAMILY Dunmanway Family Resource Centre For information on schools in the area Kilbarry Road, Dunmanway, Co. -

Roinn Cosanta. Bureau of Military History, 1913-21

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1529. Witness Patrick Wilcox. Goleen, Co. Cork. Identity. O/C Lisagriffin Coy., Schull Battn.; 0/C, Training, Cork 111 Bde., I.R.A. Subject. Activities of Lisagriffin Coy. & Schull Battn. Column, Co. Cork, 1919-1922. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil. File No S.2834. Form B.S.M.2 STATEMENT BY PATRICK WILCOX, Goleen. Co. Cork. I was born at Letter, Goleen, on March 10th 1892. My parents: were farmers. I was educated. at Lisagriffin National School until I reached the age of 15 years. When I left school I went to work on the farm at home. I joined the Royal Irish Constabulary in July, 1913, and having undergone a course of training at the Depot I was detailed for duty in North Clare. I served, in this area until I resigned from the R.I.C., on the conscription issue, on June 10th 1918. 1 then returned home. The organisation of the Volunteers in Goleeh area commenced in the summer of 1919. The organiser was Seán Lehane of Scart, Bantry. The. strength of the company in the early stages was about thirty. As the year progressed the membership increased. to about fifty. The first O/C of the unit was James. O'Mahoney, Goleen, The principal activities in the early stages were military training in close and extended order drill, manoeuvres, the care and use of firearms and organisation work. Early In 1920 Schull Battalion, which was the 7th Battalion, Cork lll Brigade, was organised by Seán Lehane. -

Heritage Bridges of County Cork

Heritage Bridges of County Cork Published by Heritage Unit of Cork County Council 2013 Phone: 021 4276891 - Email: [email protected]. ©Heritage Unit of Cork County Council 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the written permission of the publisher. Paperback - ISBN No. 978-0-9525869-6-8 Hardback - ISBN No. 978-0-9525869-7-5 Neither the authors nor the publishers (Heritage Unit of Cork County Council) are responsible for the consequences of the use of advice offered in this document by anyone to whom the document is supplied. Nor are they responsible for any errors, omissions or discrepancies in the information provided. Printed and bound in Ireland by Carraig Print inc. Litho Press Carrigtwohill, Co. Cork, Ireland. Tel: 021 4883458 List of Contributors: (those who provided specific information or photographs for use in this publication (in addition to Tobar Archaeology (Miriam Carroll and Annette Quinn), Blue Brick Heritage (Dr. Elena Turk) , Lisa Levis Carey, Síle O‟ Neill and Cork County Council personnel). Christy Roche Councillor Aindrias Moynihan Councillor Frank O‟ Flynn Diarmuid Kingston Donie O‟ Sullivan Doug Lucey Eilís Ní Bhríain Enda O‟Flaherty Jerry Larkin Jim Larner John Hurley Karen Moffat Lilian Sheehan Lynne Curran Nelligan Mary Crowley Max McCarthy Michael O‟ Connell Rose Power Sue Hill Ted and Nuala Nelligan Teddy O‟ Brien Thomas F. Ryan Photographs: As individually stated throughout this publication Includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Licence number 2013/06/CCMA/CorkCountyCouncil Unauthorised reproduction infringes Ordnance Survey Ireland and Government of Ireland copyright. -

School Age Services

School Age Services No. Of Children Telephone Tusla Number Service Name Address Town County Registered Provider Age Profile Service Type Service Can Registration Date Conditions Attached Number of Service Accommodate 0599135206 / TU2020CW002SA Askea Community Childcare Centre Brownshill Road Askea Carlow Anne Bernadette Greene 0857316209 4 - 12 Yrs Combined 36 10/09/2020 Ballon Rathoe Community childcare TU2020CW004SA Facility LTD Ballon Childcare Facility Ballon Carlow Michael O'Toole 05 99159888 4 – 10 Yrs Combined 80 08/10/2020 John Sweeney Park Afterschool, TU2019CW001SA Carlow Regional Youth Service 48 John Sweeney Park Carlow Carlow Lisa Hutton 059 9168008 4 - 12 Yrs Standalone 15 20/09/2019 New Oak/Askea Afterschool, Carlow 086 0444294/ 086 TU2019CW003SA Regional Youth Service Browneshill Road Carlow Carlow Lisa Hutton 4611181 4 - 12 Yrs Standalone 20 16/10/2019 TU2021CW002SA Play and Learn Carlow Church Street, Bagenalstown Carlow Carlow Allison Farrell 0599720567 4 - 12 Yrs Combined 44 08/03/2021 Cill an Oir Afterschool, Carlow TU2019CW002SA Regional Youth Service 32 Cill an Oir Graiguecullen Carlow Lisa Hutton 059 9164757 4 - 12 Yrs Standalone 22 20/09/2019 TU2020CW001SA Little Orchard Community Service Seskin Rd Leighlinbridge Carlow Thomas Lalor 059 9722933 4 - 12 Yrs Combined 40 04/02/2020 TU2021CW005SA O'Regans Nursery and Playschool St Martins Quinagh Carlow Mary Bolger 059 9142356 4 - 12 Yrs Combined 12 13/05/2021 TU2020CW005SA Rathoe Community HUB Rathoe Rathoe Carlow Yvette Byrne 059-9148879 4 - 15 Yrs Combined 40 17/11/2020