THE REQUIREMENTS for the DEGREE of In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Club Operating Policy

PORT of PLYMOUTH CANOEING ASSOCIATION CLUB OPERATING POLICY Revision April 2018 1 RECORD OF REVISIONS TO PPCA OPERATING POLICY DOCUMENT DATE DESCRIPTION OF REVISIONS MADE AUTHORISED NOTES PERSON MAKING REVISIONS 25.1.18 1. Table inserted for record of revisions. Bob Grose, 1, 2, 3: After discussion with 2. Font colour and text centring sorted on cover Secretary Ken Hamblin, Chair page 3. ‘Revision’ on front cover changed to January 2018 4. Re-ordered table of contents: constitution and rules put first, followed by club policies. 5. Table of contents made more detailed (and automated). 6. Heading styles standardised throughout document (e.g. fonts, case, and wording). 7. Draft changes to complaints and disciplinary procedure for review by club committee. 8. Incident report section added, previous text removed 9. Updated session register and float plan (non- white-water) added (July 2017 revision). 10. Updated session register (white water) added. 11. Risk assessment section removed, replaced with new sections for sea kayaking (pending) and white water. Feb-Mar 1. Further editing of complaints and disciplinary Ken Hamblin, All items edited following 2018 procedure. Bob Grose discussion Ken Hamblin, Bob 2. Editing to make formatting consistent. KH, BG Grose, for submission to 3. Removal of duplicate appeals process. KH committee for approval. 4. Insertion of sea kayaking risk assessments BG 5. Editing incident reporting section BG 6. Table of contents updated BG April 2018 1. Addition of more detail to anti-discrimination BG Previous definitions not definitions, pp. 5, 20. comprehensive, reference to 2010 Equalities Act added on advice of committee member. -

Cambridge Canoe Club Newsletter

Volume 2, Issue 2 Cambridge Canoe Spring 2011 Club Newsletter This newsletter relies on contri- http://www.cambridgecanoeclub.org.uk butions from members. If you have been on a trip, have a point of view or news Twelve go to Devon By Charlie and Andree Bowmer write it down and send it in to Newslet- The first contingent of paddlers where we were booked in for arrived at the top of the Dart the weekend. Charlie‘s first [email protected]. Loop on a sunny Friday after- experience of white water was a Articles should be between 75 noon in February. The more couple of years ago on exactly and 150 words long and can be experienced paddlers looked this bit of river and I remember accompanied by a picture. over the parapet of the bridge thinking ‗I‘ll never be able to do and declared the water level that‘ as I walked alongside tak- very low indeed. Personally I ing photographs. Well – it just was slightly relieved, never hav- goes to show……….. Trip reports ing paddled the Dart Loop be- fore and not being absolutely Water levels were still low when we set off on the Saturday, so sure if I would be up to it. Andree ready to paddle New club house we headed off across Dartmoor I needn‘t have worried. It was a in convoy towards the River relaxed and pleasant trip down Walkham. Patrick, Melinda and It started raining on Saturday 1* course experience – a bit of a bump and scrape in Paul had joined us and Alan evening – and rained and rained places perhaps, but I felt very had come along for the ride and rained! Still it didn‘t seem Kit to buy reassured in the company of with an injured knee. -

“Slalomed” Out!

TT AALLEESS FFRROOMM TTHHEE RRIIVVEERRBBAANNKK SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2008 “Slalomed” out! I’d saved all my holiday entitlement up to have a long summer break! Jacquelyn was the first to change this when she received a rather last minute email inviting her to La Seu d’Urgell in Spain to join the GB team at the Pre Worlds where they were holding a test event for women C1. The picture is during the races, and you might notice the glove on her left hand, she had taken the skin off four knuckles in practice and they were also badly bruised; the GB Page 2 September/October 2008 physio patched her up, one of our section International which had the same format and judges lent her a cycling glove to protect her Jacquelyn joined in her K1. hand and off she went. Little were we to dream she would walk away with a bronze medal. It was a trip of events as it wasn’t only the hand that got attention, a lorry ran in the back of the hire car, took out the rear window and we could no longer open the boot of the car. It was at this point gaffer tape had more uses that just patching slalom boats. Jacquelyn is pictured with the C2 pair and our Olympic C1 silver medallist Dave Florence, they all also got bronze at the Pre Worlds. Jonathan had a great time reaching the finals in both events. The Teen Cup was divided up into U17 and U15; Jonathan was the 2nd U17 winning a paddle and extremely nice home made Czech cake, another of the GB girls also So I had to alter my holidays after that and won a cake so we had no problems with agree to work part of August. -

Cambridge Canoe Club Newsletter

Christmas Party CAMBRIDGE The CCC Christmas Party already promises to be the great social event of the new year! It is such a runaway success CANOE CLUB that it already is fully booked , but this information is enclosed for those lucky few who are on the guest list. NEWSLETTER This year’s Christmas party will be held at Peterhouse College, Trumpington Street, on the 20th of January at CHRISTMAS SPECIAL 7:00 pm. The dress code (strictly enforced by bouncers wielding paddles) is black tie. The menu is: http://www.cambridgecanoeclub.org.uk Carrot & Ginger Soup To get the club's diary of events and ad-hoc messages — about club activities by e-mail please send a blank Corn-fed Chicken Supreme Stuffed with Chestnuts & Stilton with port wine sauce message to: Creamed Carrots [email protected] Calabrese florets with basil chiffonade In case you already didn’t know, canoeing is an assumed risk, Parisienne Potatoes water contact sport. — Pear & Cardamon Tart with Saffron Creme Fraiche December 2005 — Cheese & Biscuits If you received this Newsletter by post and you would be — happy to view your Newsletter on the Cambridge Canoe Coffee & Mints Club website (with all the photos in glorious colour!) then please advise the Membership Secretary. Contact details Club Diary are shown at the end of this Newsletter. Chairman’s Chat Hare & Hound Races Three races down, four to go, so you can start now and be My first Chairman’s Chat and just in time to wish you all eligible for one of our much sought after prizes, although a very Happy Christmas! not certain what they will be yet. -

By Chris Crowhurst

By Chris Crowhurst I doubt many people would disagree with the statement that the first roll you learn is probably the hardest. This past year I have had the pleasure of working with many novice paddlers who wanted to learn their first Greenland roll; each experienced different challenges. Through my experiences of teaching I have seen three distinct categories of obstacles that people tend to experience: 1. equipment; 2. physical fitness; and 3. mental fitness. Rather than dive into the mechanics of learning your Consider moving the foot pegs to force their legs to be first roll, this article highlights the obstacles that you can in constant contact with the kayak. Remember though remove or deal with before attempting to learn to roll, that when learning we all tend to use too much pressure thereby improving your probability of success. and end up bruising our legs. Make sure appropriate padding exists, or at least warn the paddler to expect Equipment bruising and pain if they don’t have it. At their first rolling training session most people show up enthusiastically with their boats and gear, eager Spraydecks to mimic those people they have seen rolling. Many It is fairly rare to be teaching a first roll to someone are ill-equipped and do not appreciate the additional wearing a tuilik (a traditional Greenland paddling jacket challenge their equipment can create for them to learn and spray deck, combined). More often than not, that elusive first roll. first-timers show up with a nylon spraydeck which has little to no stretch in it. -

Touring . Recreation . Sit-On Kayaks BRITISH MADE

2010 let the adventure begin Touring . recreation . sit-on kayaks BRITISH MADE 36637 PER] Update Brochure.indd 1 5/5/10 9:59:15 AM PERcEPTIon kAyAkS Perception Kayaks are manufactured and distributed in Europe by us here at Gaybo Limited. We’ve been making kayaks since 1968, when Graham and Bob Goldsmith turned their desire for canoeing into one of the most successful businesses in the industry. 40 years on from building that fi rst boat you can fi nd us in our purpose built factory in southern England, producing a comprehensive range of kayaks to exacting standards on three cutting edge rotational moulding machines. We have a rich pedigree of exceptional achievements on the water with numerous fi rst descents, World Champions and Olympic Gold medal winning performances. Our reputation for industry leading quality remains constant and in the pursuit of perfection, we have pioneered the use of some of the most important materials in the development of canoeing; with Kevlar in the 1970’s and more recently introducing Superlinear Polyethylene. Today Graham and Bob continue to have a passion for paddling and like them we take pride in seeing people enjoying themselves in the boats we make. This remains as strong nowadays as it did the day we started. 2 36637 PER] Update Brochure.indd 2 5/5/10 9:59:31 AM PERcEPTIon kAyAkS perception.at one cHooSIng THE RIgwithHT BoAT water Our broad range of kayaks offers you a diverse selection of boats to suit even the most discerning of paddlers. Each kayak offers exceptional performance, stability and comfort; that’s why paddlers of all levels choose Perception. -

KAYAKING Guide for Beginners

Biseswar Prasad Neupane KAYAKING Guide for Beginners Thesis CENTRAL OSTROBOTHNIA UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Degree Programme in Business Management June 2012 ABSTRACT Department Date Author CENTRAL OSTROBOTHNIA 6.6.2012 Biseswar Prasad UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED Neupane SCIENCES Degree Programme Degree Programme in Business Management Name of thesis Kayaking Guide for Beginners Instructor Pages Birgitta Niemi, MA 24 + Appendices Supervisor Birgitta Niemi, MA The aim of the thesis is to study about the kayak and kayaking, and to provide detailed information for the beginners, about how to start kayaking and to reduce risk. With the study from different books, magazines, and online as it has been realized that each and everything has its own form and functions. In order to enjoy kayaking one should have the right information. This thesis provides the reader with necessary information about kayaking, to reduce the risks in the water. Experienced paddlers will have less risk as they are already used to with the upcoming situation; due to lack of proper information beginners bear unnecessary risk in the water. The detail information of thesis provides the paddler to handle the dangerous situation and have fun in the water. Key Words Kayaking, risk in water, fun in water, paddlers, dangerous situations TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Aim of the thesis 1 1.2 Methodology 1 2 WHAT ARE KAYAKS MADE OF 3 3 BASIC DESIGN AND OUTFITS FOR KAYAKING 5 3.1 Design of kayaks 5 3.2 Paddles 7 3.3 Essential Clothing 8 3.4 Exposure to Nature Elements 10 4 BASICS IN KAYAKING 12 4.1 Capcize drill in a kayaks 13 4.2 Paddling instructions 13 5 KAYAKING IN DIFFERENT CONDITIONS 18 6 CONCLUSION 22 REFERENCES 23 APPENDICES 1 1 INTRODUCTION Kayak is the way of thinking about the act of travelling in which one sit and propelled water with double bladed paddle. -

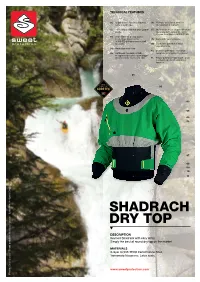

Shadrach Dry Top

TECHNICAL FEATURES 01. Super elastic Yamato neoprene, 06. Strongly articulated arms for lycra on both sides unrestricted movement 02. Thick latex bottleneck neck gasket 07. Waist seal tube of unapped Yamato inside. neoprene with easy entry velcro closure. Low friction GORE-TEX® 03. Engineered for unsurpassed freedom of movement in 08. Easy entry velcro closure GORE-TEX® Performance Shell (Coastal) 09. Thick latex bottleneck wrist gaskets inside 04. Neck tube drain hole 10. Coned super elastic Yamamoto 05. Lightweight waterproof fabric neoprene wrist protective gasket w/ taped seams and super grippy silicone elastic inner waist tube 11. Heavy duty waist tube elastic draw cord with one hand open/close function 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 Rodgers Creek Rodgers Location: SHADRACH DRY TOP Mathias Fossum Mathias DESCRIPTION Revised Shadrack with easy entry, Simply the best all round dry top on the market. MATERIALS Team paddler: Team 3-layer GORE-TEX® Performance Shell, Yamamoto Neoprene, Latex seals. Evan Garcia Evan www.sweetprotection.com Photo: TECHNICAL FEATURES 01. Super elastic Yamato neoprene, 06. Strongly articulated arms for lycra on both sides unrestricted movement 02. Thick latex bottleneck neck gasket 07. Waist seal tube of unapped Yamato inside. neoprene with easy entry velcro closure. Low friction GORE-TEX® 03. Engineered for unsurpassed freedom of movement in 08. Easy entry velcro closure GORE-TEX® Performance Shell (Coastal) 09. Thick latex bottleneck wrist gaskets inside 04. Neck tube drain hole 10. Coned super elastic Yamamoto 05. Lightweight waterproof fabric neoprene wrist protective gasket w/ taped seams and super grippy silicone elastic inner waist tube 11. -

Watertribe Rules

WaterTribe Rules "The purpose of WaterTribe is to encourage the development of boats, equipment, skills, and human athletic performance for safe and efficient coastal cruising using minimal impact human and wind powered watercraft based on kayaks, canoes, and small sailboats." – Chief, February 2000 GENERAL RULES 2 1. THE PRIME DIRECTIVE 2 2. CHANGES TO THE RULES 2 3. NO OUTSIDE AUTHORITY 2 4. NO SUPPORT 2 5. YOUR SAFETY IS YOUR RESPONSIBILITY 3 6. EXPEDITION-STYLE 3 7. EVENT DATES 3 8. EVENT CANCELLATION 3 9. NO OBLIGATION 3 10. REPAIRS 3 11. ROUTES 3 12. TIME AT CHECKPOINTS 3 13. CAMPING ALONG THE WAY 3 14. AWARD CEREMONIES 4 15. DEADLINES 4 16. MISSED DEADLINES 4 17. DROPPING OUT 4 18. WEATHER HOLDS 4 19. WEATHER HOLD NOTIFICATION 4 20. 24-HOUR REPORTING RULE 4 21. TRANSPORTATION AFTER EVENT 5 22. COAST GUARD AND REGULATION COMPLIANCE 5 23. SOME EQUIPMENT REQUIRED 5 24. HELPING OTHERS 5 25. Set-Up and Launching 5 25. LEMANS TYPE START 5 26. YIELD TO SMALLER BOATS AT THE START 6 27. DANGER 6 SAFETY ______________________________________________________________________________________________ 6 WE ACCEPT NO RESPONSIBILITY OR LIABILITY 6 YOU MUST BE AN EXPERT 6 AD HOC TEAMS 6 SHORE CONTACT PERSON 6 24-HOUR REPORTING 6 CHECK POINTS AND FLOAT PLANS 7 DROPPING OUT OR DISQUALIFICATION OR RESCUE 7 WEATHER HOLDS 8 REDUCTION OF SAIL AREA 9 PORTAGE RULES ___________________________________________________________________________________ 9 1 SELF INFLICTED PORTAGES 9 REQUIRED PORTAGES 10 TRAFFIC RULES 10 PORTAGE EQUIPMENT 10 IN-LINE SKATES NOT -

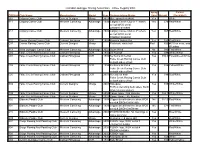

Canoe Registry 2005

Canadian Outrigger Racing Association - Canoe Registry 2005 Spray Colour CORA # Club Name Manufacturer Model Year Distinguishing Marks Skirt Weight (Deck/Hull) 500 Calgary Canoe Club Current Designs Mirage 2003 Blue spray deck #500 Yes White A11 Calgary Canoe Club Western Canoeing Advantage 1999 Calgary Canoe Club in 4" letters Yes 379 Red/White on hull WCK serial #ZWDHC015I999 A12 Calgary Canoe Club Western Canoeing Advantage 2000 Calgary Canoe Club in 4" letters Yes 367 Red/White on hull WCK serial #ZWDHC002E000 C12 Comox Racing Canoe Club Calmar Fibreglass CCR 1997 Komoux Nakolo Kai Yes 350 Red/White G07 Comox Racing Canoe Club Current Designs Mirage Red deck, white hull Red 400 #510 on nose, was Westbay A13 Delta Outrigger Canoe Club Western Canoeing Advantage 2002 South Wind No 380 Teal/White C03 False Creek Racing Canoe Club Calmar Fibreglass CCR 1994 JD Boswyk Yes 399 White/White C01 False Creek Racing Canoe Club Calmar Fibreglass CCR 1994 Ke Kumu O Ke Kai Yes 380.5 ForestGreen/White False Creek Racing Canoe Club on both sides of hull C02 False Creek Racing Canoe Club Calmar Fibreglass CCR 1994 Ke Kumu O Ka La Yes 384 Yellow/White False Creek Racing Canoe Club on both sides of hull C20 False Creek Racing Canoe Club Calmar Fibreglass CCR 2001 Herenui on bow Yes 399 Red/White False Creek Racing Canoe Club on both sides of hull G02 False Creek Racing Canoe Club Current Designs Mirage 2003 Hokupa'a Yes 389 White/White FCRCC decalling both sides, North Water decals at stern G04 False Creek Racing Canoe Club Current Designs Mirage 2004 Canoe name - Kai Hononu Yes 384.7 White/White False Creek Racing Canoe Club Current Designs Mirage 2007 Canoe Name - Ku Kanaka A02 Gibsons Paddle Club Western Canoeing Advantage 1999 Clipper decal between iakos WCK No 381.5 Red/White serial # ZWDHC009C999 A04 Gibsons Paddle Club Western Canoeing Advantage 1999 Clipper decal between iakos WCK No 374 Teal/White serial # ZWDHC007H898 A15 Gibsons Paddle Club Western Canoeing Advantage 2003 ZWDHC003D202. -

Product Workbook 2015 – 2016 Pyranha Mouldings About Us

Pyranha | P&H Sea Kayaks | Venture | Revenge PRODUCT WORKBOOK 2015 – 2016 PYRANHA MOULDINGS ABOUT US Pyranha have been manufacturing kayaks in manufacturer of canoes and kayaks. enthusiasts, we also cherish the waters where methods and implementing detailed quality the North West of England since 1971. Over the Every boat is designed by our international we enjoy our sport and we strive to reduce our control systems means we can produce truly last 44 years we have supported local paddlers team and built in Great Britain. impact on the natural environment. At Pyranha world class kayaks and help reduce our impact & world class expeditions, developed some of we make constant improvements to our whole on the environment at the same time. the most innovative products on the market, Owned and run by kayakers, we are production process to support these goals. won numerous industry awards and in the committed to being on the leading edge of Developing the most technologically advanced process become Europe's leading specialist kayak design across all our brands. As paddling materials, using industry leading processing NOTES COVER PHOTOS // BRAND TAB PHOTOS // PYRANHA PHOTO © Ondrej Pokorny/ Paddler: Gerd Serrasolses PYRANHA TAB © Leeway Collective P&H PHOTO © Stuart Yendle / Paddler: Elan Rhys P&H TAB © Bill Vonnegut / Paddler: Sean Morely VENTURE PHOTO © Glenmore Lodge VENTURE KAYAKS TAB © Chris Brain VENTURE CANOES TAB © Tim Lambert / Paddler: Pete Scutt REVENGE TAB © Paul Smith PYRANHA PYRANHA WHITEWATER KAYAKS PLAY THE RIVER pyranha.com PYRANHA LINEUP 2015 – 2016 18' 17' 16' 15' 14' 13' 12' size 11' 10' size 9' 8' 7' 6' 5' Jed Carbon Jed Loki Z.One Nano B:Two Karnali Burn III Shiva Everest 9R Fusion Fusion SOT Speeder Octane 175 Rebel TG Lite Master TG Sizes: M S, M, L S, M, L S, M, L M, L S, M, L M, L S, M, L, XL S, M, L One Size M, L S, M, L M, L One Size One Size One Size One Size One Size TECHNICAL INFO SPECIFICATIONS Model Outfi tting Length Width Volume Ext. -

January/February 2010 from the SURMANATOR…

Fred on the Tryweryn January/February 2010 FROM THE SURMANATOR… SUNDAY 9th MAY, ABINGDON DRAGON BOAT DAY (Rye Meadow) PYCC/KCC will have a stand as usual. Dave Surman and Ray KCC will be setting up from 8am. We will have a display as usual, the ERGO machine, some boats as well as a BYO BBQ. Good PR for the clubs. Would be good to get members along casu- ally to deop by and BBQ but aso a few people prepared to commit themselves to come and help. Let me know in ad- NEWS vance. It would also be possible to enter a team if someone is pre- pared to get a financial commitment from 20 people. See TRASHER CONTACT DETAILS me if you want to take on this particular Herculean task. If you have anything for the Trasher, please email to kcc. EXCITING RIVER LEVEL INFORMATION NEWS FOR [email protected], or post to KCC Trasher, 34 Elder Way, Ox- ford OX4 7GB. All contributions greatly appreciated! ALL TRASHER READERS Guys this is the most EXCITING website EVER!! Okay it says fishing-ignote that. Go register on line and you can access KCC ONLINE all the level graphs for a plethora of groovy Welsh Whitewa- Don’t forget the numerous online resources to keep in touch ter rivers. It gives a line showing mean summer and winter with KCC: levels and the level over the last 5 days. What more could Web Site www.kingfishercanoeclub.co.uk wwdude want? GO GRAB!! Diary www.google.com/calendar/embed?src=kcc.