Planetary Nebula: from Messier to Abell (What Are They, and How to Observe Them)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planetary Nebula

How Far Away Is It – Planetary Nebula Planetary Nebula {Abstract – In this segment of our “How far away is it” video book, we cover Planetary Nebula. We begin by introducing astrophotography and how it adds to what we can see through a telescope with our eyes. We use NGC 2818 to illustrate how this works. This continues into the modern use of Charge-Coupled Devices and how they work. We use the planetary nebula MyCn18 to illustrate the use of color filters to identify elements in the nebula. We then show a clip illustrating the end-of-life explosion that creates objects like the Helix Planetary Nebula (NGC 7293), and show how it would fill the space between our Sun and our nearest star, Proxima Centauri. Then, we use the Cat’s Eye Nebula (NGC 6543) to illustrate expansion parallax. As a fundamental component for calculating expansion parallax, we also illustrate the Doppler Effect and how we measure it via spectral line red and blue shifts. We continue with a tour of the most beautiful planetary nebula photographed by Hubble. These include: the Dumbbell Nebula, NGC 5189, Ring Nebula, Retina Nebula, Red Rectangle, Ant Nebula, Butterfly Nebula, , Kohoutek 4- 55, Eskimo Nebula, NGC 6751, SuWt 2, Starfish, NGC 5315, NGC 5307, Little Ghost Nebula, NGC 2440, IC 4593, Red Spider, Boomerang, Twin Jet, Calabash, Gomez’s Hamburger and others culminating with a dive into the Necklace Nebula. We conclude by noting that this will be the most likely end for our Sun, but not for billions of years to come, and we update the Cosmic Distance Ladder with the new ‘Expansion Parallax’ rung developed in this segment.} Introduction [Music @00:00 Bizet, Georges: Entracte to Act III from “Carman”; Orchestre National de France / Seiji Ozawa, 1984; from the album “The most relaxing classical album in the world…ever!”] Planetary Nebulae represent some of the most beautiful objects in the Milky Way. -

Eclipse Newsletter

ECLIPSE NEWSLETTER The Eclipse Newsletter is dedicated to increasing the knowledge of Astronomy, Astrophysics, Cosmology and related subjects. VOLUMN 2 NUMBER 1 JANUARY – FEBRUARY 2018 PLEASE SEND ALL PHOTOS, QUESTIONS AND REQUST FOR ARTICLES TO [email protected] 1 MCAO PUBLIC NIGHTS AND FAMILY NIGHTS. The general public and MCAO members are invited to visit the Observatory on select Monday evenings at 8PM for Public Night programs. These programs include discussions and illustrated talks on astronomy, planetarium programs and offer the opportunity to view the planets, moon and other objects through the telescope, weather permitting. Due to limited parking and seating at the observatory, admission is by reservation only. Public Night attendance is limited to adults and students 5th grade and above. If you are interested in making reservations for a public night, you can contact us by calling 302-654- 6407 between the hours of 9 am and 1 pm Monday through Friday. Or you can email us any time at [email protected] or [email protected]. The public nights will be presented even if the weather does not permit observation through the telescope. The admission fees are $3 for adults and $2 for children. There is no admission cost for MCAO members, but reservations are still required. If you are interested in becoming a MCAO member, please see the link for membership. We also offer family memberships. Family Nights are scheduled from late spring to early fall on Friday nights at 8:30PM. These programs are opportunities for families with younger children to see and learn about astronomy by looking at and enjoying the sky and its wonders. -

MESSIER 13 RA(2000) : 16H 41M 42S DEC(2000): +36° 27'

MESSIER 13 RA(2000) : 16h 41m 42s DEC(2000): +36° 27’ 41” BASIC INFORMATION OBJECT TYPE: Globular Cluster CONSTELLATION: Hercules BEST VIEW: Late July DISCOVERY: Edmond Halley, 1714 DISTANCE: 25,100 ly DIAMETER: 145 ly APPARENT MAGNITUDE: +5.8 APPARENT DIMENSIONS: 20’ Starry Night FOV: 1.00 Lyra FOV: 60.00 Libra MESSIER 6 (Butterfly Cluster) RA(2000) : 17Ophiuchus h 40m 20s DEC(2000): -32° 15’ 12” M6 Sagitta Serpens Cauda Vulpecula Scutum Scorpius Aquila M6 FOV: 5.00 Telrad Delphinus Norma Sagittarius Corona Australis Ara Equuleus M6 Triangulum Australe BASIC INFORMATION OBJECT TYPE: Open Cluster Telescopium CONSTELLATION: Scorpius Capricornus BEST VIEW: August DISCOVERY: Giovanni Batista Hodierna, c. 1654 DISTANCE: 1600 ly MicroscopiumDIAMETER: 12 – 25 ly Pavo APPARENT MAGNITUDE: +4.2 APPARENT DIMENSIONS: 25’ – 54’ AGE: 50 – 100 million years Telrad Indus MESSIER 7 (Ptolemy’s Cluster) RA(2000) : 17h 53m 51s DEC(2000): -34° 47’ 36” BASIC INFORMATION OBJECT TYPE: Open Cluster CONSTELLATION: Scorpius BEST VIEW: August DISCOVERY: Claudius Ptolemy, 130 A.D. DISTANCE: 900 – 1000 ly DIAMETER: 20 – 25 ly APPARENT MAGNITUDE: +3.3 APPARENT DIMENSIONS: 80’ AGE: ~220 million years FOV:Starry 1.00Night FOV: 60.00 Hercules Libra MESSIER 8 (THE LAGOON NEBULA) RA(2000) : 18h 03m 37s DEC(2000): -24° 23’ 12” Lyra M8 Ophiuchus Serpens Cauda Cygnus Scorpius Sagitta M8 FOV: 5.00 Scutum Telrad Vulpecula Aquila Ara Corona Australis Sagittarius Delphinus M8 BASIC INFORMATION Telescopium OBJECT TYPE: Star Forming Region CONSTELLATION: Sagittarius Equuleus BEST -

Messier Objects

Messier Objects From the Stocker Astroscience Center at Florida International University Miami Florida The Messier Project Main contributors: • Daniel Puentes • Steven Revesz • Bobby Martinez Charles Messier • Gabriel Salazar • Riya Gandhi • Dr. James Webb – Director, Stocker Astroscience center • All images reduced and combined using MIRA image processing software. (Mirametrics) What are Messier Objects? • Messier objects are a list of astronomical sources compiled by Charles Messier, an 18th and early 19th century astronomer. He created a list of distracting objects to avoid while comet hunting. This list now contains over 110 objects, many of which are the most famous astronomical bodies known. The list contains planetary nebula, star clusters, and other galaxies. - Bobby Martinez The Telescope The telescope used to take these images is an Astronomical Consultants and Equipment (ACE) 24- inch (0.61-meter) Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope. It has a focal ratio of F6.2 and is supported on a structure independent of the building that houses it. It is equipped with a Finger Lakes 1kx1k CCD camera cooled to -30o C at the Cassegrain focus. It is equipped with dual filter wheels, the first containing UBVRI scientific filters and the second RGBL color filters. Messier 1 Found 6,500 light years away in the constellation of Taurus, the Crab Nebula (known as M1) is a supernova remnant. The original supernova that formed the crab nebula was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Arab astronomers in 1054 AD as an incredibly bright “Guest star” which was visible for over twenty-two months. The supernova that produced the Crab Nebula is thought to have been an evolved star roughly ten times more massive than the Sun. -

Two Rings but No Fellowship: Lotr 1 and Its Relation to Planetary Nebulae

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–16 (2013) Printed 17 October 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) Two rings but no fellowship: LoTr 1 and its relation to planetary nebulae possessing barium central stars. A.A. Tyndall1,2⋆, D. Jones2, H.M.J. Boffin2, B. Miszalski3,4, F. Faedi5, M. Lloyd1, J.A. L´opez6, S. Martell7, D. Pollacco5, and M. Santander-Garc´ıa8 1Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Manchester, M13 9PL, UK 2European Southern Observatory, Alonso de C´ordova 3107, Casilla 19001, Santiago, Chile 3South African Astronomical Observatory, PO Box 9, Observatory 7935, South Africa 4Southern African Large Telescope. PO Box 9, Observatory 7935, South Africa 5Department of Physics, University of Warwick, CV4 7AL, UK 6Instituto de Astronom´ıa, Universidad Nacional Aut´onoma de M´exico, Ensenada, Baja California, C.P. 22800, Mexico 7Australian Astronomical Observatory, North Ryde, 2109 NSW, Australia 8Observatorio Astron´omico National, Madrid, and Centro de Astrobiolog´ıa, CSIC-INTA, Spain Accepted xxxx xxxxxxxx xx. Received xxxx xxxxxxxx xx; in original form xxxx xxxxxxxx xx ABSTRACT LoTr 1 is a planetary nebula thought to contain an intermediate-period binary central star system ( that is, a system with an orbital period, P, between 100 and, say, 1500 days). The system shows the signature of a K-type, rapidly rotating giant, and most likely constitutes an accretion-induced post-mass transfer system similar to other PNe such as LoTr 5, WeBo 1 and A70. Such systems represent rare opportunities to further the investigation into the formation of barium stars and intermediate period post-AGB systems – a formation process still far from being understood. -

Download This Article (Pdf)

244 Trimble, JAAVSO Volume 43, 2015 As International as They Would Let Us Be Virginia Trimble Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697-4575; [email protected] Received July 15, 2015; accepted August 28, 2015 Abstract Astronomy has always crossed borders, continents, and oceans. AAVSO itself has roughly half its membership residing outside the USA. In this excessively long paper, I look briefly at ancient and medieval beginnings and more extensively at the 18th and 19th centuries, plunge into the tragedies associated with World War I, and then try to say something relatively cheerful about subsequent events. Most of the people mentioned here you will have heard of before (Eratosthenes, Copernicus, Kepler, Olbers, Lockyer, Eddington…), others, just as important, perhaps not (von Zach, Gould, Argelander, Freundlich…). Division into heroes and villains is neither necessary nor possible, though some of the stories are tragic. In the end, all one can really say about astronomers’ efforts to keep open channels of communication that others wanted to choke off is, “the best we can do is the best we can do.” 1. Introduction astronomy (though some of the practitioners were actually Christian and Jewish) coincided with the largest extents of Astronomy has always been among the most international of regions governed by caliphates and other Moslem empire-like sciences. Some of the reasons are obvious. You cannot observe structures. In addition, Arabic astronomy also drew on earlier the whole sky continuously from any one place. Attempts to Greek, Persian, and Indian writings. measure geocentric parallax and to observe solar eclipses have In contrast, the Europe of the 16th century, across which required going to the ends (or anyhow the middles) of the earth. -

September 2020 BRAS Newsletter

A Neowise Comet 2020, photo by Ralf Rohner of Skypointer Photography Monthly Meeting September 14th at 7:00 PM, via Jitsi (Monthly meetings are on 2nd Mondays at Highland Road Park Observatory, temporarily during quarantine at meet.jit.si/BRASMeets). GUEST SPEAKER: NASA Michoud Assembly Facility Director, Robert Champion What's In This Issue? President’s Message Secretary's Summary Business Meeting Minutes Outreach Report Asteroid and Comet News Light Pollution Committee Report Globe at Night Member’s Corner –My Quest For A Dark Place, by Chris Carlton Astro-Photos by BRAS Members Messages from the HRPO REMOTE DISCUSSION Solar Viewing Plus Night Mercurian Elongation Spooky Sensation Great Martian Opposition Observing Notes: Aquila – The Eagle Like this newsletter? See PAST ISSUES online back to 2009 Visit us on Facebook – Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Newsletter, Night Visions Page 2 of 27 September 2020 President’s Message Welcome to September. You may have noticed that this newsletter is showing up a little bit later than usual, and it’s for good reason: release of the newsletter will now happen after the monthly business meeting so that we can have a chance to keep everybody up to date on the latest information. Sometimes, this will mean the newsletter shows up a couple of days late. But, the upshot is that you’ll now be able to see what we discussed at the recent business meeting and have time to digest it before our general meeting in case you want to give some feedback. Now that we’re on the new format, business meetings (and the oft neglected Light Pollution Committee Meeting), are going to start being open to all members of the club again by simply joining up in the respective chat rooms the Wednesday before the first Monday of the month—which I encourage people to do, especially if you have some ideas you want to see the club put into action. -

OBSERVING BASICS by GUY MACKIE

OBSERVING BASICS by GUY MACKIE Observing Reports The colorful and detailed photographs we see of celestial objects are not at all like the ubiquitous "fuzzy blobs" we see at the eyepiece. Nevertheless, you are freezing your buns off and loosing much needed sleep for work, the next day so why not make a description of your observations that will make the hunt worthwhile. Here are some suggestions to fill the empty spaces in your logbook and to imprint the observing experience more deeply in your memory. The Basics Your website www.m51.ca has a downloadable log sheet template that is just super, but you can also make up one for yourself or customize the website version to your own needs. The main things to start your report should be the circumstances under which you observed: Observing Location Time (of observing session and of the observation of each object) Optics (type of instrument, eyepiece, filters, power of magnification) Transparency (page 56 of the Observers Handbook) Seeing (for me this is a subjective rating of the atmospheric stability based on Planet features and double star observations) It is good to know the field of view (FOV) of each of your eyepieces in minutes of degree, then you can estimate the approximate size of the object. The sketchpad I use has the FOV for every eyepiece I use taped to the back, a handy reference. To calculate your field of view there are websites that will punch out the both the magnification and the FOV for most eyepieces. You can do it yourself: With any motor drives turned off, place a star near the celestial equator just outside the field of view in the eyepiece so that it will drift across the middle of the field of view. -

Deep-Sky Objects - Autumn Collection an Addition To: Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Third Edition RASC NW Cons Object Mag

Deep-Sky Objects - Autumn Collection An addition to: Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Third Edition RASC NW Cons Object Mag. PSA Observation Notes: Chart RA Dec Chart 1) Date Time 2 Equipment) 3) Notes # Observing Notes # Sgr M24 The Sagittarias Star Cloud 1. Mag 4.60 RA 18:16.5 Dec -18:50 Distance: 10.0 2. (kly)Star cloud, 95’ x 35’, Small Sagittarius star cloud 3. lies a little over 7 degrees north of teapot lid. Look for 7,8 dark Lanes! Wealth of stars. M24 has dark nebula 67 (interstellar dust – often visible in the infrared (cooler radiation)). Barnard 92 – near the edge northwest – oval in shape. Ref: Celestial Sampler Floating on Cloud 24, p.112 Sgr M18 - 1. RA 18 19.9, Dec -17.08 Distance: 4.9 (kly) 2. Lies less than 1deg above the northern edge of M24. 3 8 Often bypassed by showy neighbours, it is visible as a 67 small hazy patch. Note it's much closer (1/2 the distance) as compared to M24 (10kly) Sgr M17 (Swan Nebula) and M16 – HII region 1. Nebula and Open Clusters 2. 8 67 M17 Wikipedia 3. Ref: Celestial Sampler p. 113 Sct M11 Wild Duck Cluster 5.80 1. 18:51.1 -06:16 Distance: 6.0 (kly) 2. Open cluster, 13’, You can find the “wild duck” cluster, 3. as Admiral Smyth called it, nearly three degrees west of 67 8 Aquila’s beak lying in one of the densest parts of the summer Milky Way: the Scutum Star Cloud. 9 64 10 Vul M27 Dumbbell Nebula 1. -

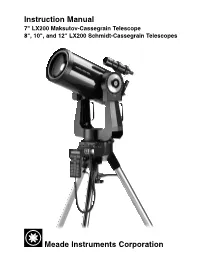

Instruction Manual Meade Instruments Corporation

Instruction Manual 7" LX200 Maksutov-Cassegrain Telescope 8", 10", and 12" LX200 Schmidt-Cassegrain Telescopes Meade Instruments Corporation NOTE: Instructions for the use of optional accessories are not included in this manual. For details in this regard, see the Meade General Catalog. (2) (1) (1) (2) Ray (2) 1/2° Ray (1) 8.218" (2) 8.016" (1) 8.0" Secondary 8.0" Mirror Focal Plane Secondary Primary Baffle Tube Baffle Field Stops Correcting Primary Mirror Plate The Meade Schmidt-Cassegrain Optical System (Diagram not to scale) In the Schmidt-Cassegrain design of the Meade 8", 10", and 12" models, light enters from the right, passes through a thin lens with 2-sided aspheric correction (“correcting plate”), proceeds to a spherical primary mirror, and then to a convex aspheric secondary mirror. The convex secondary mirror multiplies the effective focal length of the primary mirror and results in a focus at the focal plane, with light passing through a central perforation in the primary mirror. The 8", 10", and 12" models include oversize 8.25", 10.375" and 12.375" primary mirrors, respectively, yielding fully illuminated fields- of-view significantly wider than is possible with standard-size primary mirrors. Note that light ray (2) in the figure would be lost entirely, except for the oversize primary. It is this phenomenon which results in Meade 8", 10", and 12" Schmidt-Cassegrains having off-axis field illuminations 10% greater, aperture-for-aperture, than other Schmidt-Cassegrains utilizing standard-size primary mirrors. The optical design of the 4" Model 2045D is almost identical but does not include an oversize primary, since the effect in this case is small. -

2012 Annual Progress Report and 2013 Program Plan of the Gemini Observatory

2012 Annual Progress Report and 2013 Program Plan of the Gemini Observatory Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc. Table of Contents 0 Executive Summary ....................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction and Overview .............................................................................. 5 2 Science Highlights ........................................................................................... 6 2.1 Highest Resolution Optical Images of Pluto from the Ground ...................... 6 2.2 Dynamical Measurements of Extremely Massive Black Holes ...................... 6 2.3 The Best Standard Candle for Cosmology ...................................................... 7 2.4 Beginning to Solve the Cooling Flow Problem ............................................... 8 2.5 A Disappearing Dusty Disk .............................................................................. 9 2.6 Gas Morphology and Kinematics of Sub-Millimeter Galaxies........................ 9 2.7 No Intermediate-Mass Black Hole at the Center of M71 ............................... 10 3 Operations ...................................................................................................... 11 3.1 Gemini Publications and User Relationships ............................................... 11 3.2 Science Operations ........................................................................................ 12 3.2.1 ITAC Software and Queue Filling Results .................................................. -

When Aspherical Cosmic Bubbles Betray a Difficult Marriage

When aspherical cosmic bubbles betray a difcult marriage A study of binary central stars of Planetary Nebulae Henri M.J. Boffin (ESO) Brent Miszalski, D. Frew, A. Moffat, A. Acker, J. Köppen, Q. Parker, R. Corradi, D. Jones, M. Santander-Garcia, P. Rodriguez-Gil, M. Rubio-Diez 2011年10月27日木曜日 Outline The zoo of planetary nebulae Explaining their shape and common envelope evolution The search for binary central stars Morphology affected by binarity? A barium-rich central star discovered Summary 2011年10月27日木曜日 2011年10月27日木曜日 2011年10月27日木曜日 2011年10月27日木曜日 2011年10月27日木曜日 2011年10月27日木曜日 Balick et al./NASA/HST 2011年10月27日木曜日 2011年10月27日木曜日 SN 1987A Eta Car Necklace MyCn18 Menzel 3 2011年10月27日木曜日 V. Icke 2011年10月27日木曜日 Cosmic Ant 2011年10月27日木曜日 Hourglass Nebula MyCn18 2011年10月27日木曜日 HST WFPC2 2011年10月27日木曜日 HST ACS 2011年10月27日木曜日 Causes for density contrasts? Rapid rotation and/or Magnetic fields? 2011年10月27日木曜日 Causes for density contrasts? Rapid rotation and/or Magnetic fields? • Models can reproduce some of the features when no feedback on field is introduced • But require strong fields (not detected) • Need a dynamo to keep the field (Nordhaus et al. 2007) 2011年10月27日木曜日 Causes for density contrasts? Rapid rotation and/or Magnetic fields? Models can reproduce some of the features But require strong fields, not detected Need a dynamo to keep the field 2011年10月27日木曜日 Causes for density contrasts? Rapid rotation and/or Magnetic fields? Binary star? 2011年10月27日木曜日 Causes for density contrasts? Rapid rotation and/or Magnetic fields? Binary star? jets (accretion discs) predicted (common envelope evolution; mass transfer by wind) post-AGB (pre-PNe) 2011年10月27日木曜日 Boffin & Miszalski, 2011 2011年10月27日木曜日 A binary containing 2 WDs! Boffin et al. 2011 2011年10月27日木曜日 Common envelope evolution Credit: STScI 2011年10月27日木曜日 Common envelope evolution Credit: STScI 2011年10月27日木曜日 Boffin et al.