Why the United States Anti-Doping Agency's Performance-Enhanced Adjudications Should Be Treated As State Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 USA Olympic Team Trials: Men's Marathon Media Guide Supplement

2004 U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Men’s Marathon Guide Supplement This publication is intended to be used with “On the Roads” special edition for the U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Men’s Marathon Guide ‘04 Male Qualifier Updates in 2004: Stats for the 2004 Male Qualifiers as of OCCUPATION # January 20, 2004 (98 respondents) Athlete 31 All data is for ‘04 Entrants Except as Noted Teacher/Professor 16 Sales 13 AVERAGE AGE Coach 10 30.3 years for qualifiers, 30.2 for entrants Student 5 (was 27.5 in ‘84, 31.9 in ‘00) Manager 3 Packaging Engineer 1 Business Owner 2 Pediatrician 1 AVERAGE HEIGHT Development Manager 2 Physical Therapist 1 5’'-8.5” Graphics Designer 2 Planner 1 Teacher Aide 2 AVERAGE WEIGHT Researcher 1 U.S. Army 2 140 lbs. Systems Analyst 1 Writer 2 Systems Engineer 1 in 2004: Bartender 1 Technical Analyst 1 SINGLE (60) 61% Cardio Technician 1 Technical Specialist 1 MARRIED (38) 39% Communications Specialist 1 U.S. Navy Officer 1 Out of 98 Consultant 1 Webmaster 1 Customer Service Rep 1 in 2000: Engineer 1 in 2000: SINGLE (58) 51% FedEx Pilot 1 OCCUPATION # MARRIED (55) 49% Film 1 Teacher/Professor 16 Out of 113 Gardener 1 Athlete 14 GIS Tech 1 Coach 11 TOP STATES (MEN ONLY) Guidance Counselor 1 Student 8 (see “On the Roads” for complete list) Horse Groomer 1 Sales 4 1. California 15 International Ship Broker 1 Accountant 4 2. Michigan 12 Mechanical Engineer 1 3. Colorado 10 4. Oregon 6 Virginia 6 Contents: U.S. -

LE STATISTICHE DELLA MARATONA 1. Migliori Prestazioni Mondiali Maschili Sulla Maratona Tabella 1 2. Migliori Prestazioni Mondial

LE STATISTICHE DELLA MARATONA 1. Migliori prestazioni mondiali maschili sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 1) 2h03’38” Patrick Makau Musyoki KEN Berlino 25.09.2011 2) 2h03’42” Wilson Kipsang Kiprotich KEN Francoforte 30.10.2011 3) 2h03’59” Haile Gebrselassie ETH Berlino 28.09.2008 4) 2h04’15” Geoffrey Mutai KEN Berlino 30.09.2012 5) 2h04’16” Dennis Kimetto KEN Berlino 30.09.2012 6) 2h04’23” Ayele Abshero ETH Dubai 27.01.2012 7) 2h04’27” Duncan Kibet KEN Rotterdam 05.04.2009 7) 2h04’27” James Kwambai KEN Rotterdam 05.04.2009 8) 2h04’40” Emmanuel Mutai KEN Londra 17.04.2011 9) 2h04’44” Wilson Kipsang KEN Londra 22.04.2012 10) 2h04’48” Yemane Adhane ETH Rotterdam 15.04.2012 Tabella 1 2. Migliori prestazioni mondiali femminili sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 1) 2h15’25” Paula Radcliffe GBR Londra 13.04.2003 2) 2h18’20” Liliya Shobukhova RUS Chicago 09.10.2011 3) 2h18’37” Mary Keitany KEN Londra 22.04.2012 4) 2h18’47” Catherine Ndereba KEN Chicago 07.10.2001 1) 2h18’58” Tiki Gelana ETH Rotterdam 15.04.2012 6) 2h19’12” Mizuki Noguchi JAP Berlino 15.09.2005 7) 2h19’19” Irina Mikitenko GER Berlino 28.09.2008 8) 2h19’36’’ Deena Kastor USA Londra 23.04.2006 9) 2h19’39’’ Sun Yingjie CHN Pechino 19.10.2003 10) 2h19’50” Edna Kiplagat KEN Londra 22.04.2012 Tabella 2 3. Evoluzione della migliore prestazione mondiale maschile sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 2h55’18”4 Johnny Hayes USA Londra 24.07.1908 2h52’45”4 Robert Fowler USA Yonkers 01.01.1909 2h46’52”6 James Clark USA New York 12.02.1909 2h46’04”6 -

Friday Night State Track and Field P..R.Eliminaries

800 Lincoln (Birmingham, Los Angeles) all MV AL non-qualifiers: Monique Dale Friday night •Heat 1: I, Vondre Armour (Bakers• at 6-8; 8, Mike Browning (EI.Capitan). (Logan) 45.22. State track and field field) 1:54.16; 2, Issac Turner (Bur• Jon R~bY (Corcoran) qualified at 6-7. bank) 1:55.11. CCS non-qualifiers: Mike Scatena 200 P..r.eliminaries Heat 2: I, Jesse Camp (EI Capitan) (Leland) 6-2. Leyalle Beloney (Del Heat 1: 1, Marion Jones (Thousand '. 'At 2eIntos CoIege, Norwalk 1:55.12; 2, Adrian Garcia (Roosevelt, Mar) 6-7. Oaks) 23.12; 2, Bisa Grant (Bishop Fresno) 1:55.36;3, Paul DeLa Cerda MV AL non-qualifiers: None. ~ Two top athletes and relay teams (Hart) 1:55.92. O'Dowd) 23.96; 3, Tai-Ne Gibson from each of three heats, with excep• (Morlngside) 24.53; tion of the 1,600, plus the next three Heat 3: 1, Nathan Woods (Durarte) Long jump Heat 2: I, Andrea Anderson (Long fastest runners or teams from the 1:54.12;2, Tad Heath (Foothill, Santa 1, Derrick Mitchell (M!.Eden, Hay• Ana) 1:54.86;3, Matt Silva (San Pas• Beach Poly) 23.77;2, Kelli White (Lo• three heats advanced to Saturday's ward) 24-4 112w; 2, Bryan Clark (Fre• gan, Union City) 24.33;3, Lisa Bittner finals. In the 1,600, the top three qual, Escondido) 1:54.87; 4, Anthony mont, Los Angeles) 24-1/4; 3, Edward (Leigh, San Jose) 24.88. Wheeler (Dorsey, Los Angeles) 1:56.07. -

Doha 2018: Compact Athletes' Bios (PDF)

Men's 200m Diamond Discipline 04.05.2018 Start list 200m Time: 20:36 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Rasheed DWYER JAM 19.19 19.80 20.34 WR 19.19 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 20.08.09 2 Omar MCLEOD JAM 19.19 20.49 20.49 AR 19.97 Femi OGUNODE QAT Bruxelles 11.09.15 NR 19.97 Femi OGUNODE QAT Bruxelles 11.09.15 3 Nethaneel MITCHELL-BLAKE GBR 19.94 19.95 WJR 19.93 Usain BOLT JAM Hamilton 11.04.04 4 Andre DE GRASSE CAN 19.80 19.80 MR 19.85 Ameer WEBB USA 06.05.16 5 Ramil GULIYEV TUR 19.88 19.88 DLR 19.26 Yohan BLAKE JAM Bruxelles 16.09.11 6 Jereem RICHARDS TTO 19.77 19.97 20.12 SB 19.69 Clarence MUNYAI RSA Pretoria 16.03.18 7 Noah LYLES USA 19.32 19.90 8 Aaron BROWN CAN 19.80 20.00 20.18 2018 World Outdoor list 19.69 -0.5 Clarence MUNYAI RSA Pretoria 16.03.18 19.75 +0.3 Steven GARDINER BAH Coral Gables, FL 07.04.18 Medal Winners Doha previous Winners 20.00 +1.9 Ncincihli TITI RSA Columbia 21.04.18 20.01 +1.9 Luxolo ADAMS RSA Paarl 22.03.18 16 Ameer WEBB (USA) 19.85 2017 - London IAAF World Ch. in 20.06 -1.4 Michael NORMAN USA Tempe, AZ 07.04.18 14 Nickel ASHMEADE (JAM) 20.13 Athletics 20.07 +1.9 Anaso JOBODWANA RSA Paarl 22.03.18 12 Walter DIX (USA) 20.02 20.10 +1.0 Isaac MAKWALA BOT Gaborone 29.04.18 1. -

Harding University High School Lesson Plan

Harding University High School Lesson Plan Teacher: Prior Subject: Health ATOD: Day 1 ESSENTIAL STANDARD/OBJECTIVE: 9.ATOD.1.1- Explain the short-term & long term effects of performance-enhancing drugs on health & eligibility to participate in sports BENCHMARK: 9ATOD.1.1 Examine 4 professional athletes evaluating the long and short term effects of steroids on their health and sports eligibility. WARM UP: Steroids quiz to obtain prior knowledge. After students have completed quiz allow them to switch papers with their elbow partner and check for accuracy. ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS: What are the long and short term effects of steroids on my health and sports eligibility? Is there a situation where you can justify using performance enhancing drugs? Support your answer. 21ST CENTURY SKILL(S): GLOBAL CONNECTIONS: REAL-WORLD Children must also take an CONNECTIONS: active role in accessing and Tour deFrance and steroids… Barry Bonds appropriately using ABC video clip Mark McGuire information which affects Lance Armstrong their health. Marian Jones Florence Griffin-Jorner MATERIALS NEEDED: TECHNOLOGY: LITERACY Journals, videos, PowerPoint, video clips INCORPORATED: graphic organizer, Journal writing, article tape, Choosing the review, foldables (graphic Best book, water bottle organizer) Introduction of New Material: Today you will learn the long and short term health risks associated with the use of performance enhancing drugs like steroids. We will examine 4-6 professional athletes and analyze how steroid use affected their health as well as their sports careers. Modeling: • Power point • Video Guided Practice: Teaching Steps: • Warm up review • Vocabulary: performance-enhancing, eligibility, steroid • Power point presentation • Article review (Various Articles) 1. -

BRONZO 2016 Usain Bolt

OLIMPIADI L'Albo d'Oro delle Olimpiadi Atletica Leggera UOMINI 100 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 Usain Bolt (JAM), Justin Gatlin (USA), Andre De Grasse (CAN) 2012 Usain Bolt (JAM), Yohan Blake (JAM), Justin Gatlin (USA) 2008 Usain Bolt (JAM), Richard Thompson (TRI), Walter Dix (USA) 2004 Justin Gatlin (USA), Francis Obikwelu (POR), Maurice Greene (USA) 2000 Maurice Greene (USA), Ato Boldon (TRI), Obadele Thompson (BAR) 1996 Donovan Bailey (CAN), Frank Fredericks (NAM), Ato Boldon (TRI) 1992 Linford Christie (GBR), Frank Fredericks (NAM), Dennis Mitchell (USA) 1988 Carl Lewis (USA), Linford Christie (GBR), Calvin Smith (USA) 1984 Carl Lewis (USA), Sam Graddy (USA), Ben Johnson (CAN) 1980 Allan Wells (GBR), Silvio Leonard (CUB), Petar Petrov (BUL) 1976 Hasely Crawford (TRI), Don Quarrie (JAM), Valery Borzov (URS) 1972 Valery Borzov (URS), Robert Taylor (USA), Lennox Miller (JAM) 1968 James Hines (USA), Lennox Miller (JAM), Charles Greene (USA) 1964 Bob Hayes (USA), Enrique Figuerola (CUB), Harry Jeromé (CAN) 1960 Armin Hary (GER), Dave Sime (USA), Peter Radford (GBR) 1956 Bobby-Joe Morrow (USA), Thane Baker (USA), Hector Hogan (AUS) 1952 Lindy Remigino (USA), Herb McKenley (JAM), Emmanuel McDonald Bailey (GBR) 1948 Harrison Dillard (USA), Norwood Ewell (USA), Lloyd LaBeach (PAN) 1936 Jesse Owens (USA), Ralph Metcalfe (USA), Martinus Osendarp (OLA) 1932 Eddie Tolan (USA), Ralph Metcalfe (USA), Arthur Jonath (GER) 1928 Percy Williams (CAN), Jack London (GBR), Georg Lammers (GER) 1924 Harold Abrahams (GBR), Jackson Scholz (USA), Arthur -

CORRECTIONS to INTERNATIONAL ATHLETICS ANNUAL 1986 in Addition to Those Shown on Pages 588 and 589 of the 1986 Annual

CORRECTIONS TO INTERNATIONAL ATHLETICS ANNUAL 1986 In addition to those shown on pages 588 and 589 of the 1986 Annual. Note that lists amendments will also affect the indexes. 1985 World Lists - Men Page 279 100m add 10.2A M.Elizondo MEX 284 200m add 20.6A Jesus Aguilasocho MEX 60 288 400m add 45.9A Jesus Aguilasocho MEX 60 290 800m Antonio Paez 1:46.88 (4) Bern 16 Aug (not 1:47.26) 302 5000m Toshihiko Seko 13:35.4 (1) Tokyo 22 Jun (from 13:36.28) 304 10000m Shuichi Yoneshige 28:26.8 (1) Ageo 20 Oct (from 28:39.04) add: Takeyuki Nakayama JAP 60 28:26.9 (1) Uji 16 Nov 305 Jose Zapata VEN 28:47.5. add Takao Nakamura JAP 58 28:31.91 (2) Kobe 29 Apr, Kazuyoshi Kudo JAP 61 28:37.7 (1) Yokohama 4 Nov, Shozo Shimojo JAP 57 28:42.2 12 May, Satoshi Kato JAP 61 28:47.5 4 Nov 310 Mar add Yoshiharu Nakai JAP 60 2:13:24 (1) Hofu 22 Dec 311 add Yasuro Hiraoka JAP 61 2:13:53 22 Dec, Takaski Kaneda JAP 60 2:13:59 22 Dec, Masayuki Nishi JAP 2:14:31 22 Dec 314 110mh add Hiroshi Kakimori JAP 68 14.13 -0.1 21 Oct 316 add Masahiro Sugii JAP 63 14.05 3.2 24 Oct 318 400mh add Hiroshi Kakimori JAP 68 50.03 (1) Ise 31 Aug 319 add Yao Yongzhi CHN 50.62 (1) Nanjing 23 Oct 322 HJ add Satoru Nonaka JAP 63 2.27 (1) Tottori 24 Oct 323 Takao Sakamoto 2.24 (2) 2 Jun Tokyo (from 2.23); delete 2.23 Inaoka; add Liu Yunping CHN 2.24 Guangzhou 4 Mar, Cai Shu CHN 62 2.21 4 Mar, Motochika Inoue JAP 66 2.21i 10 Mar, Takashi Katamine JAP 2.21 2 Jun, Eiji Kito JAP 60 2.21 24 Oct 327 PV Liang Xuereng CHN 5.50 (1) Beijing 27 Jul (from 5.48), Ji Zebao 5.40 Shanghai 8 Jun (from 5.35), -

In-Class Exercise

PROBLEM SET 3—STATS 210 Due: July 29, 2004 1. A group of researchers was studying lifetime lead exposure and IQ in 7-year old kids. They classified 100 children as having “high,” “medium,” or “low” exposure based on the lead concentrations in their teeth (using baby teeth that had fallen out). Then they measured their IQ on a standard, age-appropriate IQ test, the results of which are known to have a nice normal distribution in the population. The following multiple linear regression equation resulted: IQ = 100 + (-2)*(1 if exposure=medium, 0 if low or high) + (-10)*(1 if exposure=high, 0 if low or medium) Regression coefficients: βˆ = −2; s.e.(βˆ ) = .5 1 1 ˆ ˆ β 2 = −10; s.e.(β 2 ) = .8 a. What is the p-value for the test of the null hypothesis that β1=0? That β2=0? Note: Regression coefficients are a test statistic (like a mean or difference in means), and thus have a sampling distribution. The sampling distribution of an estimated regression coefficient ˆ ˆ is a t-distribution: β ~ Tn−k (β , s.e.(β ) ): where n is the sample size; k is the number of estimated coefficients in the model, including the intercept; β is the “true” slope between the predictor and outcome; and the standard error of β represents the variability that we expect to see in estimates of β based on sample sizes of n. ˆ ˆ Correspondingly, the null distribution of β is β ~ Tn−k (0, s.e.(β ) ); (a slope of 0 indicates no relationship between the predictor and the outcome). -

2021 : RRCA Distance Running Hall of Fame : 1971 RRCA DISTANCE RUNNING HALL of FAME MEMBERS

2021 : RRCA Distance Running Hall of Fame : 1971 RRCA DISTANCE RUNNING HALL OF FAME MEMBERS 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 Bob Cambell Ted Corbitt Tarzan Brown Pat Dengis Horace Ashenfleter Clarence DeMar Fred Faller Victor Drygall Leslie Pawson Don Lash Leonard Edelen Louis Gregory James Hinky Mel Porter Joseph McCluskey John J. Kelley John A. Kelley Henigan Charles Robbins H. Browning Ross Joseph Kleinerman Paul Jerry Nason Fred Wilt 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 R.E. Johnson Eino Pentti John Hayes Joe Henderson Ruth Anderson George Sheehan Greg Rice Bill Rodgers Ray Sears Nina Kuscsik Curtis Stone Frank Shorter Aldo Scandurra Gar Williams Thomas Osler William Steiner 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 Hal Higdon William Agee Ed Benham Clive Davies Henley Gabeau Steve Prefontaine William “Billy” Mills Paul de Bruyn Jacqueline Hansen Gordon McKenzie Ken Young Roberta Gibb- Gabe Mirkin Joan Benoit Alex Ratelle Welch Samuelson John “Jock” Kathrine Switzer Semple Bob Schul Louis White Craig Virgin 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 Nick Costes Bill Bowerman Garry Bjorklund Dick Beardsley Pat Porter Ron Daws Hugh Jascourt Cheryl Flanagan Herb Lorenz Max Truex Doris Brown Don Kardong Thomas Hicks Sy Mah Heritage Francie Larrieu Kenny Moore Smith 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 Barry Brown Jeff Darman Jack Bacheler Julie Brown Ann Trason Lynn Jennings Jeff Galloway Norm Green Amby Burfoot George Young Fred Lebow Ted Haydon Mary Decker Slaney Marion Irvine 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Ed Eyestone Kim Jones Benji Durden Gerry Lindgren Mark Curp Jerry Kokesh Jon Sinclair Doug Kurtis Tony Sandoval John Tuttle Pete Pfitzinger 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Miki Gorman Patti Lyons Dillon Bob Kempainen Helen Klein Keith Brantly Greg Meyer Herb Lindsay Cathy O’Brien Lisa Rainsberger Steve Spence 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Deena Kastor Jenny Spangler Beth Bonner Anne Marie Letko Libbie Hickman Meb Keflezighi Judi St. -

Newsletternewsletter

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ Volume 46, No. 14 NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER ■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■track December 29, 2000 ISAHAYA, December 2—10,000: 1. Women: 4 x 400: 1. North HS 3:39.46; 2. — International Results — Nagata (Jpn) 27:53.19. Wilson HS 3:39.64. JSM Heptathlon, Claremont, June 6–7— ALGERIA KENYA Women: Hept: 1. Meyer (CaHS) 5038 (15.68, ALGIERS, August 2—Women: 800: 1. 1/ 3/ CHAMPS, Nairobi, July 22—10,000: 6. 5-4 2/1.64, 34- 4/10.38, 25.71 [2914—1], Mérah-Benida (Alg) 1:59.68. 1/ W. Kiptum (Ken) 28:07.37. 18-11 4/5.77, 103-4/31.50, 2:18.9 [2124]). ALGIERS, August 6—800: Guerni (Alg) 1:44.28. POLAND FLORIDA Florida A&M USTCA, Tallahassee, April AUSTRALIA SKÓRCZ, June 1—HT: 1. Boulge (Pol) 250-0 (76.20). 22—Women: 200(4.8): 1. Guthrie (FlAM) SYDNEY, November 18—Women: HT: 1. WROCLAW, September 6—Women: 23.60w. Eagles (Aus) 212-9 (64.86). 400H: 1. Pskit (Pol) 55.86; 2. Olichwierczuk MELBOURNE, November 30—Women: (Pol) 56.22. MINNESOTA 400: 1. Richards (Jam) 52.70. HS SUB-Sectional, Albertville, May 25— SYDNEY, December 3—Women: HT: 1. Women: PV: 1. Manuel (MnHS) 13-4 (4.06) Eagles (Aus) 218-4 (66.55). NEW ZEALAND High School Record (old HSR 13-3 O’Hara MELBOURNE, December 4—10,000: 1. HAMILTON, November 18—Women: DT: [CaHS] ’98). L. Kipkosgei (Ken) 27:57.11; 2. A. Chebii (Ken) 1. Faumuina (NZ) 189-10 (57.87). 28:23.95. Women: 10,000: 1. -

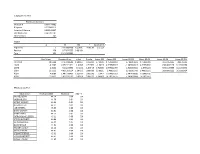

Multiple Linear Regression Summary with Estimations

SUMMARY OUTPUT Regression Statistics Multiple R 0.999779982 R Square 0.999560013 Adjusted R Square 0.999543837 Standard Error 0.040787787 Observations 142 ANOVA df SS MS F Significance F Regression 5 514.0060938 102.8012 61792.81 2.5E-226 Residual 136 0.22625553 0.001664 Total 141 514.2323493 Coefficients Standard Error t Stat P-value Lower 95% Upper 95% Lower 95.0% Upper 95.0% Lower 95.0% Upper 95.0% Intercept -18.6244 9.797298689 -1.900973 0.059421 -37.99916 0.750348891 -37.99915832 0.75034889 -49.22364245 489.76683 100M -0.4783 0.457221671 -1.04605 0.297394 -1.38246 0.425906943 -1.382460343 0.42590694 -238.0867176 31.2339268 200M 2.4202 0.23233896 10.4165 4.83E-19 1.960694 2.879622395 1.960693566 2.8796224 -10.54125909 112.304955 2/1 R -13.2512 4.931303514 -2.687163 0.008106 -23.00317 -3.49926311 -23.00316792 -3.49926311 -209.8882236 36.0316964 4/1 R 4.8089 1.446738463 3.323969 0.001141 1.9479 7.669926563 1.947900086 7.66992656 4/2 R 11.0633 2.892392193 3.82496 0.000199 5.343402 16.78316515 5.343402446 16.7831651 RESIDUAL OUTPUT Observation Predicted 400M Residuals ABS - V MICHAEL BERRY 44.79 -0.04 0.04 JASON ROUSER 44.76 0.01 0.01 JEREMY WARINER 43.46 -0.01 0.01 NATHON ALLEN 44.21 -0.02 0.02 JOE HERRERA 46.64 0.00 0.00 DANNY EVERETT 43.81 0.00 0.00 JERRY HARRIS 44.73 -0.01 0.01 PATRICK BLAKE LEEPER 45.11 -0.06 0.06 STEVEN GARDINER 43.89 -0.02 0.02 DAJUAN HARDING 46.09 -0.05 0.05 DAVID NEVILLE 44.61 0.00 0.00 WILBERT LONDON 44.50 -0.03 0.03 DAVID VERBURG 44.41 0.00 0.00 STEWART TREVOR 45.63 0.00 0.00 LASHAWN MERRITT 43.67 -0.02 0.02 -

BASL Vol 12 Issue 2

B VOLUME 12 · ISSUE 2 · 2004 R I T I S H A S S O C I A T I O N F O R Sport and the Law S P O R T A N D L Registered Office: A W c/o Pridie Brewster L I 1st Floor · 29-39 London Road M I T Journal Twickenham · Middlesex · TW1 3SZ E D Telephone: 020 8892 3100 Facsimile: 020 8892 7604 S P O R T A N D L A W J O U R N A m L V O L U M E h 1 2 · 4 I S S } U E : 2 T t 2 0 0 7 4 q &v?$ OLns Registered Office: c/o Pridie Brewster 1st Floor · 29-39 London Road Twickenham · Middlesex · TW1 3SZ Telephone: 020 8892 3100 Facsimile: 020 8892 7604 www.basl.org Postgraduate Certificate Editor Simon Gardiner in Sports Law Directors Maurice Watkins: President The School of Law at King’s College London · issues for individual athletes: doping, Murray Rosen QC: Chairman offers a one-year, part-time postgraduate discipline, player contracts, endorsement Mel Goldberg: Deputy Chairman course in sports law, leading to a College contracts, civil and criminal liability for Gerry Boon: Hon. Treasurer Postgraduate Certificate in Sports Law. sports injuries; Karena Vleck: Hon. Secretary The course is led by programme director · EC law and sport: competition law, freedom Darren Bailey Jonathan Taylor, partner and head of the Sports of movement; and Nick Bitel Law Group at Hammonds, who teaches the Walter Cairns course along with other leading sports law · comparative sports law: the North American Edward Grayson practitioners including Adam Lewis, Nick Bitel, Model of Sport.