Chapter-Iii Transition from Pre-Modern to Modern Baroda State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resource, Valuable Archive on Social and Economic History in Western India

H-Asia Resource, Valuable archive on social and economic history in Western India Discussion published by Sumit Guha on Friday, September 2, 2016 Note on a valuable new resource: Haribhakti Collection Department of History, Faculty of Arts The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara, Gujarat-INDIA Foundation: 1949 Eighteenth Century Baroda in Gujarat has not only evidenced the emergence of political potentates in Gaekwads but also the pecuniary mainstays amongst citizens. The foremost were the Haribhaktis’[i]; who are remembered for business success in areas such as money-lending/indigenous banking, coin- changing, traders in private capacity and banking; formation of Gaekwad’s State financial policy- which stimulated rural resources and commercial economy that benefitted in the making of urban Gujarat during the 18th and 19th centuries; and as philanthropists in individual capability. The business acumen and continuous support to Gaekwad fetched honours and titles like Nagar‘ Seth’ and ‘Raj Ratan' ‘Raj Mitra’ ‘Chiranjiva’&c to them by rulers and citizens. Their firm building in Vadodara dates back to last quarter of 19th century; and its location is near Mandvi darwaza in Ghadiali pol popularly known as Haribhakti ni Haveli “…made up of red and yellow wood and …stands as grandeur of 200 years past”. This family as state bankers were Kamvisadars, traders and Nagarseths of Gaekwad`s of Baroda. Their multifunctional role is apparent as we have more than 1000bahis/ account books and around 10,000 loose sheets of correspondence and statements;kundlis, astrological charts, receipts of transactions related to religious donations, grants for educational and health infrastructure, greetings, invitations, admiration and condolence letters etc. -

Chapter II: Study Area

Chapter II: Study Area CHAPTER II: STUDY AREA 2.0 Description of the Study area: Vadodara district is one of the most important districts of Gujarat. It is a leading agriculture district and one of the main contributors to the agricultural production in the state. 2.1 Geographical Location: Vadodara District is a district in the eastern part of the state of Gujarat in western India. It lies between latitudes 21° 45’ and 22° 45’ North and longitudes 72° 48’ and 74° 15’ East having a geographical area of 7,550 km². The district is bounded by Panchmahal and Dahod districts to the North, Anand and Kheda to the West, Bharuch and Narmada districts to the South, and the state of Madhya Pradesh to the East. Administratively, the district is subdivided into twelve talukas, viz. Vadodara, 28 Chapter II: Study Area Karjan, Padra, Savli, Dabhoi, Sankheda, Waghodia, Jetpur Pavi, Chhota Udepur, Naswadi, Tilakwada and Sinor. In the present work, part of Vadodara district is selected as a site of the study area which includes portions from Vadodara, Padra, Dabhoi and Waghodia talukas. Site of study area is shown in map given below (Figure 4). Fig 4. Map showing site of study area The Mahi River passes through the district. Orsang, Dhadhar, Dev, Goma, Jambuva, Vishwamitri, Bhukhi Heran, Mesari, Karad, Men, Ani, Aswini and Sukhi are the small rivers. Minor irrigation dams are constructed across Sukhi and Rami rivers. Geographically, the district comprises of Khambhat Silt in the south-west, Mahi plain in the north-west, Vadodara plain in the middle, Orsang-Heran plain in the mid-east, Vindhyan hills in the east and Narmada gorge in the south-east which merges westwards 29 Chapter II: Study Area with the lower Narmada Valley. -

To Study the Storm Water Drainage of Ahmedabad, Gandhinagar and Vadodara City

Volume : 2 | Issue : 4 | April 2013 ISSN - 2250-1991 Research Paper Engineering To Study the Storm Water Drainage of Ahmedabad, Gandhinagar and Vadodara City * Kanan Y. Patel ** Shibani Chourushi * W.R.M., L. D. College of Engineering, Ahmedabad ** W.R.M., L. D. College of Engineering, Ahmedabad ABSTRACT This paper describes the study urban storm drainage performance indicators. The paper begins by presenting a general framework of objectives and performance indicators as logical intermediate steps between values and the decisions taken to reflect them. The paper then con- siders practical approaches toperformance and indicator measurement, based on field experience in India. General conclusions about drainage performance indicators are then presented, stressing the challenge of finding indicators which are valid indicators of performance. Keywords : Drainage; Flooding; Indicators; Objectives; Performance INTRODUCTION Infrastructure is important in eradicating poverty through vari- ous job creation opportunities and by so doing, it enables to speed up economic development and ultimately ensures im- proved quality of life. For example, the increase in population generates greater infrastructure demand, urban storm water drainage facilities. When urban Storm water drainage facilities are not properly provided nor integrated in a given urban area, the perfor- mance of infrastructure can be limited. Problems like flood- ing and erosion when persistent can shorten the life span of road infrastructures and other urban utilities. With urbaniza- tion, permeability increases because of the increase in im- pervious surfaces. This in turn changes the drainage pattern, increases overland flow resulting in flooding and related -en vironmental problems. The impact of this is severe on spatial structures like road. -

Roshni JULY to SEPTEMBER 2020

Members of Purva Vidarbha Mahila Parishad, Nagpur, Celebrate Ganesh Chaturthi Roshni JULY TO SEPTEMBER 2020 ALL INDIA Women’s ConferenCE Printed at : I G Printers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi-110020 Maharashtra Celebrates Ganesh Chaturthi Ganesh Puja at the home of President -AIWC, Ganesh Puja at the home of President -Mumbai Branch, Smt. Sheela Kakde Smt. Harsha Ladhani Independence Day Celebrations at Head Office Ganesh Puja at Pune Mahila Mandal ROSHNI Contents Journal of the All India Women's Conference Editorial ...................................................................... 2 July - September 2020 President`s Keynote Address at Half Yearly Virtual Meeting .................................... 3 EDITORIAL BOARD -by Smt. Sheela Kakde Editor : Smt. Chitra Sarkar Assistant Editor : Smt. Meenakshi Kumar Experience at Hathras ............................................... 6 Advisors : Smt. Rekha A. Sali -by Smt. Kuljit. Kaur : Smt. Sheela Satyanarayan Editorial Assistants : Smt. Ranjana Gupta An Incident in Hyderabad… How we reacted .... 10 : Smt. Sujata Shivya -by Smt. Geeta Chowdhary President : Smt. Sheela Kakde Maharani Chimnabai II Gaikwad Secretary General : Smt. Kuljit Kaur Treasurer : Smt. Rehana Begum The Illustrious First President of AIWC. .............. 11 -by Smt. Shevata Rai Talwar, Patrons : Smt. Kunti Paul : Dr. Manorama Bawa Are Prodigies Made or Born- A Tribute : Smt. Gomathi Nair to Sarojini Naidu ...................................................... 15 : Smt. Bina Jain -by Smt. Veena Kohli, Patron, AIWC : Smt. Veena Kohli : Smt. Rakesh Dhawan Mangal Murti- Our Hope in the Pandemic ......... 19 -by Smt. Rekha A. Sali AIWC has Consultative Status with UN Observer's Status with UNFCCC Report of Four Zonal Webinars:All India Permanent Representatives : Smt. Sudha Acharya and Women’s Conference `CAUSE PARTNER’ Smt. Seema Upleker (ECOSOC) (UNICEF) of National Foundation for Communal AIWC has affiliation with International Harmony. -

BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Baroda Archives - Southern Circle , Vadodara Unpublished (Huzur Political Office) 1

BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Baroda Archives - Southern Circle , Vadodara Unpublished (Huzur Political Office) 1. Section No - 1, General Dafter No. 1, File Nos. 1 to 8 2. Section No - 11, General Dafter No - 16, File Nos. 1 to 13 3. Section No - 12, General Dafter No - 19, File No - 1 4. Section No - 13, General Dafter No - 20, File Nos - 1 to 6 - A 5. Section No - 14, General Dafter No - 2, File No - 1 6. Section No - 16, General Dafter No - 10, File Nos - 1 to 19 7. Section No - 38, General Dafter No - 8, File Nos - 1 to 8 - B 8. Section No - 65, General Dafter No - 112, File No - 11 9. Section No - 67, General Dafter No - 117, File Nos - 30 to 35 10. Section No.73, General Dafter No. 456, File Nos - 1 to 6 - A 11. Section No - 75, General Dafter No - 457, File No - 1 12. Section No - 77, General Dafter No - 461, File Nos - 11 & 12 13. Section No - 78, General Daft er No - 463, File No - 1 14. Section No - 80, General Dafter No - 466, File Nos - 1 & 2 15. Section No - 88, General Dafter No - 440, File Nos - 1 to 4 16. Section No - 88, General Dafter No - 441, File No - 25 17. Section No - 103, General Dafter No - 143, File Nos - 37 & 38 18. Section No - 177, General Dafter No - 549, File Nos - 1 to 7 19. Section No177, General Dafter No - 550, File Nos - 4 to 16 20. Section No - 199, General Dafter No - 478, File Nos - 1 to 17 21. -

Quarantine Centres in Gujarat Name of Hotel/ Room Contact Quaranti Rate(Includ Person(Gov Sl

Quarantine Centres in Gujarat Name of Hotel/ Room Contact Quaranti Rate(includ Person(Gov Sl. ne ing meals Contact Person Contact t. official in No. District Type: Centre: Email Phone and taxes) (Hotel/Centre) Number Charge) Contact no. Remarks 1 GANDHINAG On Yatri Inn nrgfounda 9898111112 Category Mr. Jitendra 9898111112 N.S.Salvi, 9978405243 Note: AR Payment tion@yah 1:1500 Patel Executive Taxes and oo.co.in engineer, food charges are extra. 2 MAHESANA On Gratis Yatri nrgfounda 9978259072 Category Jayantibhai 9978259072 SHRI 8511231433 Bhavan, tion@yah 1:0 Joitaram Patel B.J.BHARW oo.co.in AD 3 Mahisagar On Vrundav nrgfounda 9426575806 Category Manager 9426575806 Ms. Neha 9978405954 Note: Payment an Hotel tion@yah 1:900 Gupta Taxes are oo.co.in Category extra. 2:900 4 RAJKOT On Gratis Vrajbho nrgfounda 7567009541 Category Mr.G.V.Miyani,P 7567009541 SHRI 9909970214 omi tion@yah 1:0 rant R.S.UPADHY Aashram oo.co.in Officer,Dhoraji AY , 5 NARMADA On Vraj nrgfounda 9099943335 Category Dr. Kashyap 9099943335 Dr. Kashyap 9099943335 Note: GST Payment Hotel tion@yah 1:3000 extra. Rajpipla oo.co.in 6 MORBI On Vibhav nrgfounda 9879444680 Category Himanshubhai 9879444680 Harshaben 9827558330 Note: Payment Hotel tion@yah 1:1500 Patel Taxes are oo.co.in extra. For AC- +Food Rs.3000/- 7 RAJKOT On Gratis Vataliya nrgfounda 7990147421 Category Mr.Charansinh 7990147421 SHRI 9909970214 Prajapati tion@yah 1:0 Gohil,Prant R.S.UPADHY Samaj oo.co.in officer,Rajkot AY Vadi City-2 &a mp; Chhatral aya 8 RAJKOT On Gratis Vataliya nrgfounda 7990147421 Category Mr.Charansinh 7990147421 SHRI 9909970214 Prajapati tion@yah 1:0 Gohil R.S.UPADHY Samaj oo.co.in AY Vadi & Chhatral aya 9 GANDHINAG On Varun nrgfounda 9624066786 Category Mr. -

List of Stadiums in India

Stadiums in India Stadium State Vivekananda Yuba Bharati Krirangan (VYBK) Kolkata, West Bengal Eden Gardens Kolkata, West Bengal Rajiv Gandhi International Cricket Stadium Hyderabad, Telangana Kaloor International Stadium Kochi, Kerala Greenfield International Stadium / The Sports Hub Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala DY Patil Sports Stadium Mumbai, Maharahstra EMS Corporation Stadium Kozhikode, Kerala Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium Ahmedabad, Gujarat Shaheed Veer Narayan Singh International Cricket Stadium Naya Raipur, Chhattisgarh Barabati Stadium Cuttack, Odisha Vidarbha Cricket Association Stadium Nagpur, Maharashtra Feroz Shah Kotla Ground New Delhi Dr. Bhupen Hazarika Cricket Stadium (Barsapara Stadium) Guwahati, Assam Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology Stadium Bhubaneswar, Odisha JSCA International Stadium Complex Ranchi, Jharkhand M. Chinnaswamy Stadium Bengaluru, Karnataka M. A. Chidambaram Stadium (Chepauk Stadium) Chennai, Tamil Nadu Maharashtra Cricket Association Stadium Pune, Maharashtra CB Patel International Cricket Stadium Surat, Gujarat Birsa Munda Athletics Stadium Ranchi, Jharkhand JRD Tata Sports Complex Stadium Jamshedpur, Jharkhand Wankhede Stadium Mumbai, Maharashtra Green Park Stadium Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh Saurashtra Cricket Association Stadium (Khandheri Cricket Stadium) Rajkot, Gujarat GMC Balayogi Athletic Stadium Hyderabad, Telangana Kanchenjunga Stadium Siliguri, West Bengal Khuman Lampak Main Stadium Imphal, Manipur Maharaja Bir Bikram College Stadium Agartala, Tripura Barkatullah Khan Stadium Jodhpur, -

Creative Space,Vol

Creative Space,Vol. 5, No. 2, Jan. 2018, pp. 59–70 Creative Space Journal homepage: https://cs.chitkara.edu.in/ Alternative Modernity of the Princely states- Evaluating the Architecture of Sayajirao Gaekwad of Baroda Niyati Jigyasu Chitkara School of Planning and Architecture, Chitkara University, Punjab Email: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Received: August 17, 2017 The first half of the 20th century was a turning point in the history of India with provincial rulers Revised: October 09, 2017 making significant development that had positive contribution and lasting influence on India’s growth. Accepted: November 21, 2017 They served as architects, influencing not only the socio-cultural and economic growth but also the development of urban built form. Sayajirao Gaekwad III was the Maharaja of Baroda State from 1875 Published online: January 01, 2018 to 1939, and is notably remembered for his reforms. His pursuit for education led to establishment of Maharaja Sayajirao University and the Central Library that are unique examples of Architecture and structural systems. He brought many known architects from around the world to Baroda including Keywords: Major Charles Mant, Robert Chrisholm and Charles Frederick Stevens. The proposals of the urban Asian modernity, Modernist vision, Reforms, planner Patrick Geddes led to vital changes in the urban form of the core city area. Architecture New materials and technology introduced by these architects such as use of Belgium glass in the flooring of the central library for introducing natural light were revolutionary for that period. Sayajirao’s vision for water works, legal systems, market enterprises have all been translated into unique architectural heritage of the 20th century which signifies innovations that had a lasting influence on the city’s social, economic, administrative structure as well as built form of the city and its architecture. -

2 In-Depth Analysis of Existing Situation

Vadodara Municipal Corporation In-depth analysis of existing situation 2 IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS OF EXISTING SITUATION Vadodara, the third largest city in the state of Gujarat, is one of the focal points of industrial growth in Western India. The city became a metropolis in 1991, along with eleven other major cities across the country, by crossing the one million-population mark. 2.1 DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE OF VADODARA The city has witnessed high growth (40%) from 1981 to 1991. However, it could not maintain the momentum of growth; the growth rate slowed down to 26% in the last decade, 1991--2001. The population registered in 2001 was 13.06 lakhs as against 10.31 lakhs 1991. The compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) has been steadily declining from 4.64% in 1971-81 to 3.45% in 1981-1991, and further to 2.39 % in 1991-2001. The population in 2005 has been estimated at Table 1. Population of Vadodara around 14.69 lakhs. The population projection Year Population Average annual for 2011 is estimated around 17.54 lakhs and is (lakhs) growth rate (%) based on the hypothesis that the city would 1981 7.34 4.64% grow at a constant rate due to the increasing 1991 10.31 3.45% urbanisation in the state. The trend also shows 2001 13.06 2.39% that the population would increase at a 2005 (Estimated) 14.69 2.99% stabilised average annual growth rate of 2.99% 2011 (Projected) 17.54 2.99% from 2005 to 2011. Source: Census 2001 The population density of the city has increased from 9527 per sq.km in 1991 to 12064 per sq.km in 2001. -

Important Stadiums in India & World

Is Now In CHENNAI | MADURAI | TRICHY | SALEM | COIMBATORE | CHANDIGARH | BANGALORE|NAMAKKAL|ERODE|PUDUCHERRY www.raceinstitute.in | www.bankersdaily.in IMPORTANT STADIUMS IN INDIA & WORLD Chennai: #1, South Usman Road, T Nagar. | Madurai: #24/21, Near Mapillai Vinayagar Theatre, Kalavasal. | Trichy: opp BSNL office, Juman Center, 43 Promenade Road, Cantonment. | Salem: #209, Sonia Plaza / Muthu Complex, Junction Main Rd, State Bank Colony, Salem. | Coimbatore #545, 1st floor, Adjacent to SBI (DB Road Branch), Diwan Bahadur Road, RS Puram, Coimbatore (Kovai) – 641002 | Chandigarh: SCO 131-132 Sector 17C. | Bangalore. H.O: 7601808080 / 9043303030 | www.raceinstitute.in Important Stadiums in India: 1. Wankhede Stadium Mumbai, Maharashtra Cricket 2. Feroz Shah Kotla Ground Delhi Cricket 3. M.A. Chidambaram Stadium Chennai , Tamil Nadu Cricket 4. Eden Gardens Kolkata, West Bengal Cricket 5. Gymkhana Ground Mumbai , Maharashtra Cricket 6. Jsca Stadium Ranchi, Jharkhand Cricket 7. Subrata Roy Sahara Stadium Pune , Maharashtra Cricket 8. Rajiv Gandhi International Stadium Hyderabad, Telangana Cricket 9. Barkatullah Khan Stadium Jodhpur, Rajasthan Cricket 10. Jawahar Lal Nehru Stadium Kochi, Kerala Multipurpose ( football (soccer) and cricket) 11. K.D. Singh Babu Stadium Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Multipurpose 12. Fatorda Stadium Margao, Goa Football & Cricket 13. Maulana Azad Stadium Jammu, Jammu & Kashmir Cricket 14. Indira Priyadarshini Stadium Visakhapatnam, Andhra Cricket Pradesh 15. University Stadium Thiruvananthapuram, Multi-purpose Kerala 16. Roop Singh Stadium Gwalior , Madhya Pradesh Cricket 17. Nehru Stadium Pune, Maharashtra Multipurpose 18. Jawahar Lal Nehru Stadium Delhi Multipurpose 19. Keenan Stadium Jamshedpur , Jharkhand Multipurpose 20. Sardar Patel Stadium Ahmedabad , Gujarat Cricket 21. Moti Bagh Stadium Vadodara , Gujarat Cricket 22. Sher-I-Kashmir Stadium Srinagar, Jammu & Cricket Kashmir 23. -

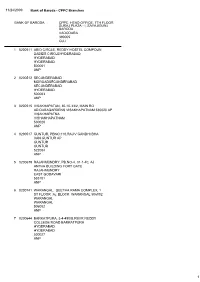

CPPC Branches BANK of BARODA CPPC, HEAD OFFICE, 7TH

11/24/2009 Bank of Baroda - CPPC Branches BANK OF BARODA CPPC, HEAD OFFICE, 7TH FLOOR SURAJ PLAZA - I, SAYAJIGUNJ BARODA VADODARA 390005. GUJ 1 0200511 ABID CIRCLE, REDDY HOSTEL COMPOUN DABIDS CIRCLEHYDERABAD HYDERABAD HYDERABAD 500001 ANP 2 0200512 SECUNDERABAD MGROADSECUNDERABAD SECUNDERABAD HYDERABAD 500003 ANP 3 0200515 VISAKHAPATAN, 30-10-33/2, MAIN RO AD DABAGARDENS VISAKHAPATNAM 530020 AP VISAKHAPATNA VISHAKHAPATNAM 530020 ANP 4 0200517 GUNTUR, PBNO:110,RAJIV GANDHI BHA VAN GUNTUR AP GUNTUR GUNTUR 522004 ANP 5 0200679 RAJAHMUNDRY, PB.NO-4, 31-1-40, AJ ANTHA BUILDING FORT GATE RAJAHMUNDRY EAST GODAVARI 533101 ANP 6 0200741 WARANGAL, SEETHA RAMA COMPLEX, 1 ST FLOOR `A¿ BLOCK WARANGAL 506002 WARANGAL WARANGAL 506002 ANP 7 0200644 BARKATPURA, 3-4-490/B,RBVR REDDY COLLEGE ROAD BARKATPURA HYDERABAD HYDERABAD 500027 ANP 1 11/24/2009 Bank of Baroda - CPPC Branches 8 0200939 CHARMINAR, 22-7-264, NIZAMBAGH, D IWAN DEODI CHARMINAR HYDERABAD HYDERABAD 500002 ANP 9 0200954 KHAIRATABAD, 6-1-84,KHUSRUJUNG HO USESECRETARIAT RDSAIFABAD HYDERABAD HYDERABAD 500004 ANP 10 0201264 ZAFARGARH, DOOR NO.1-51/1, MAIN R D MANDAL GHANPUR STN GHANPUR WARANG GHANPUR WARANGAL 506144 ANP 11 0201262 MARREDPALLY, WEST MARREDPALLY MAI N ROAD SECUNDERABAD SECUNDERABAD HYDERABAD 500026 ANP 12 0201312 NARMETTA, H.NO.4-98/1,MAIN RD.NAR METTAWARANGAL DT NARMETTA WARANGAL 506167 ANP 13 0201324 KADIPI KONDA, MAIN ROAD, KAZIPET, WARANGAL DIST AP WARANGAL WARANGAL 506003 ANP 14 0201809 JUBILEE HILL, PLOT 217 ROAD 17 JU BILEE HILLS HYDERABAD HYDERABAD HYDERABAD 500033 ANP -

Dadabhai Naoroji

UNIT – IV POLITICAL THINKERS DADABHAI NAOROJI Dadabhai Naoroji (4 September 1825 – 30 June 1917) also known as the "Grand Old Man of India" and "official Ambassador of India" was an Indian Parsi scholar, trader and politician who was a Liberal Party member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom House of Commons between 1892 and 1895, and the first Asian to be a British MP, notwithstanding the Anglo- Indian MP David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre, who was disenfranchised for corruption after nine months. Naoroji was one of the founding members of the Indian National Congress. His book Poverty and Un-British Rule in India brought attention to the Indian wealth drain into Britain. In it he explained his wealth drain theory. He was also a member of the Second International along with Kautsky and Plekhanov. Dadabhai Naoroji's works in the congress are praiseworthy. In 1886, 1893, and 1906, i.e., thrice was he elected as the president of INC. In 2014, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg inaugurated the Dadabhai Naoroji Awards for services to UK-India relations. India Post depicted Naoroji on stamps in 1963, 1997 and 2017. Contents 1Life and career 2Naoroji's drain theory and poverty 3Views and legacy 4Works Life and career Naoroji was born in Navsari into a Gujarati-speaking Parsi family, and educated at the Elphinstone Institute School.[7] He was patronised by the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad III, and started his career life as Dewan (Minister) to the Maharaja in 1874. Being an Athornan (ordained priest), Naoroji founded the Rahnumai Mazdayasan Sabha (Guides on the Mazdayasne Path) on 1 August 1851 to restore the Zoroastrian religion to its original purity and simplicity.