Whitchurch Historic Town Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admissions Arrangements Policy

ADMISSION ARRANGEMENTS For Year 7 entry in September 2021 & In-year admissions from September 2020 (Sections A-C) 1 ADMISSIONS ARRANGEMENTS FOR OUSEDALE SCHOOL A. BACKGROUND The ethos of Ousedale School is expressed in its mission statement: in which it strives to provide: Students with the knowledge, confidence and skills to contribute and compete successfully locally, nationally and globally because they were educated at Ousedale School. Our school motto is for the school community to Aspire, Believe, Achieve: Aspire: Students, supported by staff and parents, are motivated to aim high in everything they do. They are encouraged to aspire to new heights: academically, practically and through the acquisition of new skills. Core values are promoted and opportunities provided for staff and students to demonstrate these on a daily basis. Believe: Students, with staff, develop resilience and self-belief in their ability to reach challenging targets and develop new skills. Achieve: Students achieve outstanding results and take responsibility for their learning enabling them to progress onto pathways of their choice and participate fully in the life of the school. We ask all parents/carers applying for a place to respect this ethos and its importance to the school community. 2 B. AREA SERVED BY OUSEDALE SCHOOL – THE DEFINED AREA The school serves the two most northern towns in Milton Keynes, Newport Pagnell and Olney. Students in years 7 to 11 will attend one of the campuses (later referred to as the ‘designated campus’) of Ousedale School as follows; students living outside the defined area are considered for the campus they live closest to: Newport Pagnell Campus for children living in: Astwood, Chicheley, Gayhurst, Hardmead, Lathbury, Little Linford, Moulsoe, Newport Pagnell, North Crawley, Sherington and Stoke Goldington. -

153 Bus Time Schedule & Line Map

153 bus time schedule & line map 153 Aylesbury - Weedon - Aston Abbotts - Cubblington View In Website Mode - Stewkley The 153 bus line (Aylesbury - Weedon - Aston Abbotts - Cubblington - Stewkley) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Aylesbury: 11:05 AM (2) Stewkley: 2:25 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 153 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 153 bus arriving. Direction: Aylesbury 153 bus Time Schedule 19 stops Aylesbury Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Stockhall Crescent, Stewkley Stockhall Crescent, Stewkley Civil Parish Tuesday Not Operational Village Hall, Stewkley Wednesday 11:05 AM Library, Stewkley Thursday Not Operational School Lane, Stewkley Friday Not Operational Dove Street, Stewkley Saturday Not Operational The Carpenters' Arms Ph, Stewkley Kings Street, Stewkley Kiln Farm, Stewkley 153 bus Info Direction: Aylesbury Crossroads, Cublington Stops: 19 Trip Duration: 33 min Hay Barn Business Park, Aston Abbotts Line Summary: Stockhall Crescent, Stewkley, Village Hall, Stewkley, Library, Stewkley, Dove Street, The Green, Aston Abbotts Stewkley, The Carpenters' Arms Ph, Stewkley, Kiln The Green, Aston Abbotts Civil Parish Farm, Stewkley, Crossroads, Cublington, Hay Barn Business Park, Aston Abbotts, The Green, Aston East End, Weedon Abbotts, East End, Weedon, The Five Elms Ph, Weedon, Weedon Hill Farm, Weedon, The Horse & The Five Elms Ph, Weedon Jockey Ph, Aylesbury, Whaddon Chase, Aylesbury, The New Zealand Ph, Aylesbury, The -

Milton Keynes Theme Report - 2011 Census Population and Migration

Milton Keynes Theme Report - 2011 Census Population and Migration Introduction This report outlines the key facts around population and migration in Milton Keynes from the 2011 Census. Key Points • Milton Keynes has a very high population growth rate. The population increased by 36,100 people (17%) to 248,800 between 2001 and 2011. • Population change between 2001 and 2011 was not evenly spread across Milton Keynes. • The Milton Keynes population has a younger profile than the England average. The average age in Milton Keynes is 35 compared with 39 for England. • The highest growth rate between 2001 and 2011 in Milton Keynes occurred in the older age groups and the 0-4 age group. • The population is becoming more ethnically diverse. In 2001 13.2% of the population were from a black and minority ethnic group compared with 26.1% in 2011. • Different ethnic groups have different age profiles. The Mixed ethnic group had the youngest age profile and the White Irish the oldest. • The number of Milton Keynes residents born outside of the UK more than doubled from 20,500 (9.9%) in 2001 to 46,100 (18.5%) in 2011. • 90.5% of people aged 3+ in Milton Keynes have English as their main language compared to 92.0% in England. • 52.8% of the Milton Keynes population stated they were Christian, 4.8% Muslim and 2.8% Hindu. 31.3% of the population in Milton Keynes stated they had no religion. Produced by: Research and Intelligence, Milton Keynes Council April 2014 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mkiobservatory.org.uk Research and Intelligence 1 Milton Keynes Council www.mkiobservatory.org.uk Milton Keynes has a very high poopulation growth rate. -

Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes Listed Below (Aylesbury Area)

NOTICE OF ELECTION Buckinghamshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes listed below (Aylesbury Area) Number of Parish Parishes Councillors to be elected Adstock Parish Council 7 Akeley Parish Council 7 Ashendon Parish Council 5 Aston Abbotts Parish Council 7 Aston Clinton Parish Council 11 Aylesbury Town Council for Bedgrove ward 3 Aylesbury Town Council for Central ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Coppice Way ward 1 Aylesbury Town Council for Elmhurst ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Gatehouse ward 3 Aylesbury Town Council for Hawkslade ward 1 Aylesbury Town Council for Mandeville & Elm Farm ward 3 Aylesbury Town Council for Oakfield ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Oxford Road ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Quarrendon ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Southcourt ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Walton Court ward 1 Aylesbury Town Council for Walton ward 1 Beachampton Parish Council 5 Berryfields Parish Council 10 Bierton Parish Council for Bierton ward 8 Bierton Parish Council for Oldhams Meadow ward 1 Brill Parish Council 7 Buckingham Park Parish Council 8 Buckingham Town Council for Highlands & Watchcroft ward 1 Buckingham Town Council for North ward 7 Buckingham Town Council for South ward 8 Buckingham Town Council form Fishers Field ward 1 Buckland Parish Council 7 Calvert Green Parish Council 7 Charndon Parish Council 5 Chearsley Parish Council 7 Cheddington Parish Council 8 Chilton Parish Council 5 Coldharbour Parish Council 11 Cublington Parish Council 5 Cuddington Parish Council 7 Dinton with Ford & -

LCA 4.13 Cublington-Wing Plateau-1 May 08.Pdf

Aylesbury Vale District Council & Buckinghamshire County Council Aylesbury Vale Landscape Character Assessment LCA 4.13 Cublington - Wing Plateau Landscape Character Type: LCT 4 Undulating Clay Plateau B0404200/LAND/01 Aylesbury Vale District Council & Buckinghamshire County Council Aylesbury Vale Landscape Character Assessment LCA 4.13 Cublington -Wing Plateau (LCT 4) Key Characteristics Location Extending from the southern edge of Stewkley in the north, Hoggeston in the west and towards the south Bedfordshire border at • Elevated clay plateau Linslade in the east. Aston Abbotts marks the southern edge. • Extensive parliamentary and earlier fields Landscape character Clay plateau landscape with a gently undulating between settlements landform eroded by local streams. The core of the area consists of large • Pastureland and small arable fields with degraded or well trimmed hedgerows with few hedgerow scale paddocks around trees. Paddocks and smaller parcels of grazing land are located around the settlements settlements. There is mixed farming use and concentrations of smaller fields • Areas of remote on the western fringes of the LCA. The extensive former WWII airfield is landscape now used as a poultry farm with some remnant runways and MOD buildings • Open arable plateau and more recent woodland planting. There is a golf course southeast of landscape Stewkley. Generally sparse woodland cover across the area and long straight roads connecting settlements. The settlement of Wing sits on a small promontory of land overlooking the valley to the south. Distinctive Features Geology Predominantly glacial till overlain by pockets of undifferentiated • Small nucleated glacial deposits and head within the incised valleys. Large exposures of settlements Kimmeridge clays mixed with glacial deposits in the west. -

16 Bell Close Cublington Ella

16 Bell Close Cublington ella 16 Bell Close Cublington We Are Pleased To Offer For Sale This Well Presented Three Bedroom Semi-Detached Family Home Within The Ever Popular Village Of CUBLINGTON. The Property Is Positioned At The End Of A Cul-De-Sac Which Offers Amazing COUNTRYSIDE VIEWS From The Rear. Enter Into The Porch From The Front Garden & Driveway (Ideal For Coats & Boots From An Afternoon Countryside Hike), Which Leads Into The Main Entrance Hall With A Window To The Side Aspect. The Tastefully Fitted Kitchen Is Located At The Rear Of The Property With Views Over The Rear Garden And Beyond, With The Dual Aspect 21' Lounge / Dining Room Completing The Downstairs Living Space. Notable Features Within This Room Is The Fantastic Feature Fireplace & Outlook From The Dining Room Out Over Open Fields To The Rear. Up The Stairs To The First Floor Leads You To A Light Landing With Side Aspect Window With Doors To Remaining Rooms Leading From. The 11' Master Bedroom Has Fantastic COUNTRYSIDE VIEWS To The Rear Whilst The Second / Third Bedrooms Are Well Proportioned DOUBLE BEDROOMS And The Bathroom Is Tastefully Finished. Outside Areas Comprise Of Rear Garden With Established Borders, Flower Beds & Patio With Views To The Rear, Brick Store Shed To The Side, Oil Tank & Gate Leading To The Front. Outside Front Is Lawn, Hedgerow And Shingle Driveway Property Features: Three Bedrooms Re Fitted Kitchen Re Fitted Bathroom Cull De Sac Location Potential To Extend STPP Local Transport Links: Road Links: M1 Junction 13 & Junction 14 M40 Junction 9 & Junction 10 Rail Links: Milton Keynes Central Train Station Bicester North Train Station Bicester Village Train Station Aylesbury Train Station Aylesbury Vale Parkway Leighton Buzzard Train Station Guide Price: £340,000 LU7 0LH Independent Land & Estate Agents Important Notice These particulars which have been produced with the greatest of care and attention, and are only intended to give the purchaser a guide to the description of the property. -

ED113 Housing Land Supply Soundness Document (June 2018)

1 VALP Housing Land Supply Soundness document June 2018 Introduction 1.1 This document accompanies the Submission Vale of Aylesbury Local Plan (VALP). It sets out the housing trajectory and housing land supply position based on the housing requirement and allocations within the Pre Submission VALP. It shows that a 5 year housing land supply can be demonstrated at the point of adoption. 1.2 This housing trajectory and housing land supply calculation is different to that in the latest published Housing Land Supply Position Statement (currently June 2018). It takes into account the redistribution of unmet need to Aylesbury Vale which is a ‘policy on’ matter. It is not appropriate to use ‘policy on’ figures for the purposes of calculating a 5 year housing land supply in the context of determining individual planning applications because they have not been tested through examination and found sound. 1.3 The ‘policy off’ approach to calculating the five year supply for application decisions has been endorsed by recent inspectors.1 In the Waddesdon appeal (July 2017) the inspector concluded at paragraph 81 that: “Although there may be some distribution from other districts to Aylesbury Vale, and although what this figure is might be emerging, at this stage in the local plan process any redistribution would represent the application of policy and thus represent a ‘policy on’ figure. As the Courts have made clear this is not appropriate for consideration in a Section 78 appeal and I am therefore satisfied that for this appeal the OAN figure for Aylesbury Vale should be 965 dwellings per annum”. -

Updated Electorate Proforma 11Oct2012

Electoral data 2012 2018 Using this sheet: Number of councillors: 51 51 Fill in the cells for each polling district. Please make sure that the names of each parish, parish ward and unitary ward are Overall electorate: 178,504 190,468 correct and consistant. Check your data in the cells to the right. Average electorate per cllr: 3,500 3,735 Polling Electorate Electorate Number of Electorate Variance Electorate Description of area Parish Parish ward Unitary ward Name of unitary ward Variance 2018 district 2012 2018 cllrs per ward 2012 2012 2018 Bletchley & Fenny 3 10,385 -1% 11,373 2% Stratford Bradwell 3 9,048 -14% 8,658 -23% Campbell Park 3 10,658 2% 10,865 -3% Danesborough 1 3,684 5% 4,581 23% Denbigh 2 5,953 -15% 5,768 -23% Eaton Manor 2 5,976 -15% 6,661 -11% AA Church Green West Bletchley Church Green Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1872 2,032 Emerson Valley 3 12,269 17% 14,527 30% AB Denbigh Saints West Bletchley Saints Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1292 1,297 Furzton 2 6,511 -7% 6,378 -15% AC Denbigh Poets West Bletchley Poets Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1334 1,338 Hanslope Park 1 4,139 18% 4,992 34% AD Central Bletchley Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Central Bletchley Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 2361 2,367 Linford North 2 6,700 -4% 6,371 -15% AE Simpson Simpson & Ashland Simpson Village Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 495 497 Linford South 2 7,067 1% 7,635 2% AF Fenny Stratford Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Fenny Stratford Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1747 2,181 Loughton Park 3 12,577 20% 14,136 26% AG Granby Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Granby Bletchley -

Cheddington Fact Pack May 2011

The Vale of Aylesbury Plan Cheddington Fact Pack May 2011 St Giles Church Contents Section Page 1 Introduction page 3 2 Location and Setting page 6 3 Story of Place page 8 4 Fact File page 10 5 Issues Facing the Parish page 38 6 Parish Constraints page 40 7 Annex page 45 Front Cover Photo Source: AVDC, 2010 2 1. Introduction Purpose of the document This Fact Pack document was initially produced in 2010 to help inform the town/parish council about the characteristics of their parish for the ‘community view’ consultation. This consultation was undertaken early on in the preparation of the Vale of Aylesbury Plan as part of a bottom up approach embracing localism and aiming to get local communities more involved in the planning process. The town/parish council were asked to consult with their community on the following: The level of future housing and/or employment development up to 2031, including specific types of homes, employment and other development The location, sizes and phasing of development The types of infrastructure (social, community, physical) needed to enable development, including where it should be located Any other issues relating to planning and development This Fact Pack document has also been used to support neighbourhood planning by providing evidence for the context of the neighbourhood plan, including information on housing, employment, infrastructure and the environment. This Fact Pack document has also been used to support the Vale of Aylesbury Plan Settlement Hierarchy Assessment. This forms part of the evidence that classifies settlements into different categories, where different levels of growth are apportioned to over the next 20 years. -

Ma281016 Chiltern Hills Rally Road

th Sunday 17 May 2020 (third Sunday in May annually) ma281016 Chiltern Hills Rally Road Run www.chilternhillsrally.org.uk and Chiltern Hills Rally on Facebook Road Run route summary: Starting at: Aylesbury Tuck, Edison Road, Aylesbury HP19 8TE Finishing at: Chiltern Hills Rally show ground, New Road, Weedon Distance: 36 miles, Travel time 1 hour to 1 hour 30 mins Key: POI – Points of Interest View – View points Directions: 1. Turn left off Edison Road on to Rabans Lane (at 0.0 miles) 2. At the roundabout, continue straight to stay on Rabans Lane 3. At the roundabout, take the 1st exit onto Bicester Road/A41 (0.5 miles) 4. Continue to follow A41 heading out of Aylesbury towards Waddesdon POI – Quarrendon Fields wind turbine at 149m is the tallest land based turbine in the UK 5. After about 2 miles take a left turn signposted Winchendon (3.6 miles) POI – Waddesdon Manor is a country house in the village of Waddesdon. The house was built in the Neo- Renaissance style of a French château between 1874 and 1889 for Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild (1839– 1898) as a weekend residence for grand entertaining. The last member of the Rothschild family to own Waddesdon was James de Rothschild (1878–1957). He bequeathed the house and its contents to the National Trust. It is now administered by a Rothschild charitable trust that is overseen by Jacob Rothschild, 4th Baron Rothschild. It is one of the National Trust's most visited properties, with around 335,000 visitors annually. 6. Continue straight up Waddesdon Hill and through Upper Winchendon (5.5 miles) View - Just before the crossroads to Cuddington and Ashendon after Upper WInchendon- stopping area to the left with great views to the Chiltern Hills and the communications tower at Stokenchurch in the distance. -

Share 2020.Xlsx

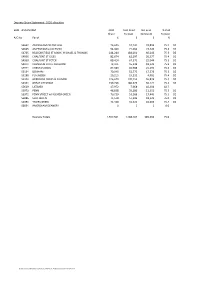

Deanery Share Statement : 2020 allocation 3AM AMERSHAM 2020 Cash Recd Bal as at % Paid Share To Date 30-Sep-20 To Date A/C No Parish £ £ £ % S4642 AMERSHAM ON THE HILL 76,635 57,741 18,894 75.3 DD S4645 AMERSHAM w COLESHILL 94,309 71,064 23,245 75.4 DD S4735 BEACONSFIELD ST MARY, MICHAEL & THOMAS 244,244 184,001 60,243 75.3 DD S4936 CHALFONT ST GILES 82,674 62,297 20,377 75.4 DD S4939 CHALFONT ST PETER 89,414 67,370 22,044 75.3 DD S4971 CHENIES & LITTLE CHALFONT 73,471 55,349 18,122 75.3 DD S4974 CHESHAM BOIS 87,583 65,988 21,595 75.3 DD S5134 DENHAM 70,048 52,770 17,278 75.3 DD S5288 FLAUNDEN 20,213 15,232 4,981 75.4 DD S5324 GERRARDS CROSS & FULMER 226,629 170,755 55,874 75.3 DD S5351 GREAT CHESHAM 239,796 180,675 59,121 75.3 DD S5629 LATIMER 17,972 7,668 10,304 42.7 S5970 PENN 46,838 35,286 11,552 75.3 DD S5971 PENN STREET w HOLMER GREEN 70,729 53,289 17,440 75.3 DD S6086 SEER GREEN 75,518 57,396 18,122 76.0 DD S6391 TYLERS GREEN 41,428 31,225 10,203 75.4 DD S6694 AMERSHAM DEANERY 0 0 0 0.0 Deanery Totals 1,557,501 1,168,107 389,394 75.0 R:\Store\Finance\FINANCE\2020\Share 2020\Share 2020Bucks Share06/10/202010:48 Deanery Share Statement : 2020 allocation 3AY AYLESBURY 2020 Cash Recd Bal as at % Paid Share To Date 30-Sep-20 To Date A/C No Parish £ £ £ % S4675 ASHENDON 4,773 3,568 1,205 74.7 DD S4693 ASTON SANDFORD 6,263 6,263 0 100.0 S4698 AYLESBURY ST MARY 50,274 22,943 27,331 45.6 S4699 AYLESBURY QUARRENDON ST PETER 5,915 4,421 1,494 74.8 DD S4700 AYLESBURY BIERTON 23,797 10,169 13,628 42.7 DD S4701 AYLESBURY HULCOTT ALL SAINTS 2,122 -

Aylesbury Vale North Locality Profile

Aylesbury Vale North Locality Profile Prevention Matters Priorities The Community Links Officer (CLO) has identified a number of key Prevention Matters priorities for the locality that will form the focus of the work over the next few months. These priorities also help to determine the sort of services and projects where Prevention Matters grants can be targeted. The priorities have been identified using the data provided by the Community Practice Workers (CPW) in terms of successful referrals and unmet demand (gaps where there are no appropriate services available), consultation with district council officers, town and parish councils, other statutory and voluntary sector organisations and also through the in depth knowledge of the cohort and the locality that the CLO has gained. The CLO has also worked with the other CLOs across the county to identify some key countywide priorities which affect all localities. Countywide Priorities Befriending Community Transport Aylesbury Vale North Priorities Affordable Day Activities Gentle Exercise Low Cost Gardening Services Dementia Services Social Gardening Men in Sheds Outreach for Carers Background data Physical Area The Aylesbury Vale North locality (AV North) is just less than 200 square miles in terms of land area (500 square kilometres). It is a very rural locality in the north of Buckinghamshire. There are officially 63 civil parishes covering the area (approximately a third of the parishes in Bucks). There are 2 small market towns, Buckingham and Winslow, and approximately 70 villages or hamlets (as some of the parishes cover more than one village). Population The total population of the Aylesbury Vale North locality (AV North) is 49,974 based on the populations of the 63 civil parishes from the 2011 Census statistics.