Aina O Ke Kupuna: Hawaiian Ancestral Crops in Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 103/Thursday, May 28, 2020

32256 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 103 / Thursday, May 28, 2020 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS closes-headquarters-open-window-and- presentation of data or arguments COMMISSION changes-hand-delivery-policy. already reflected in the presenter’s 7. During the time the Commission’s written comments, memoranda, or other 47 CFR Part 1 building is closed to the general public filings in the proceeding, the presenter [MD Docket Nos. 19–105; MD Docket Nos. and until further notice, if more than may provide citations to such data or 20–105; FCC 20–64; FRS 16780] one docket or rulemaking number arguments in his or her prior comments, appears in the caption of a proceeding, memoranda, or other filings (specifying Assessment and Collection of paper filers need not submit two the relevant page and/or paragraph Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2020. additional copies for each additional numbers where such data or arguments docket or rulemaking number; an can be found) in lieu of summarizing AGENCY: Federal Communications original and one copy are sufficient. them in the memorandum. Documents Commission. For detailed instructions for shown or given to Commission staff ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. submitting comments and additional during ex parte meetings are deemed to be written ex parte presentations and SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal information on the rulemaking process, must be filed consistent with section Communications Commission see the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In (Commission) seeks comment on several section of this document. proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) proposals that will impact FY 2020 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: of the Commission’s rules or for which regulatory fees. -

Pacific Root Crops

module 4 PACIFIC ROOT CROPS 60 MODULE 4 PACIFIC ROOT CROPS 4.0 ROOT CROPS IN THE PACIFIC Tropical root crops are grown widely throughout tropical and subtropical regions around the world and are a staple food for over 400 million people. Despite a growing reliance on imported flour and rice products in the Pacific, root crops such as taro (Colocasia esculenta), giant swamp taro (Cyrtosperma chamissonis), giant taro (Alocasia macrorhhiza), tannia (Xanthosoma sagittifolium), cassava (Manihot esculenta), sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) and yams (Dioscorea spp.) remain critically important components of many Pacific Island diets, particularly for the large rural populations that still prevail in many PICTs (Table 4.1). Colocasia taro, one of the most common and popular root crops in the region, has become a mainstay of many Pacific Island cultures. Considered a prestige crop, it is the crop of choice for traditional feasts, gifts and fulfilling social obligations in many PICTs. Though less widely eaten, yams, giant taro and giant swamp taro are also culturally and nutritionally important in some PICTs and have played an important role in the region’s food security. Tannia, cassava and sweet potato are relatively newcomers to the Pacific region but have rapidly gained traction among some farmers on account of their comparative ease of establishment and cultivation, and resilience to pests, disease and drought. Generations of accumulated traditional knowledge relating to seasonal variations in rainfall, temperature, winds and pollination, and their influence on crop planting and harvesting times now lie in jeopardy given the unparalleled speed of environmental change impacting the region. -

Weed Notes: Dioscorea Bulbifera, D. Alata, D. Sansibarensis Tunyalee

Weed Notes: Dioscorea bulbifera, D. alata, D. sansibarensis TunyaLee Morisawa The Nature Conservancy Wildland Invasive Species Program http://tncweeds.ucdavis.edu 27 September 1999 Background: Dioscorea bulbifera L. is commonly called air-potato, potato vine, and air yam. The genus Dioscorea (true yams) is economically important world-wide as a food crop. Two-thirds of the worldwide production is grown in West Africa. The origin of D. bulbifera is uncertain. Some believe that the plant is native to both Asia and Africa. Others believe that it is a native of Asia and was subsequently introduced into Africa (Hammer, 1998). In 1905, D. bulbifera was imported into Florida for scientific study. A perennial herbaceous vine with annual stems, D. bulbifera climbs to a height of 9 m or more by twining to the left. Potato vine has alternate, orbicular to cordate leaves, 10-25 cm wide, with prominent veins (Hammer, 1998). Dioscorea alata (white yam), also found in Florida, is recognizable by its winged stems. These wings are often pink on plants growing in the shade. Unlike D. bulbifera, D. alata twines to the right. Native to Southeast Asia and Indo-Malaysia, this species is also grown as a food crop. The leaves are heart-shaped like D. bulbifera, but more elongate and primarily opposite. Sometimes the leaves are alternate in young, vigorous stems and often one leaf is aborted and so the vine appears to be alternate, but the remaining leaf scar is still visible. Stems may root and develop underground tubers that can reach over 50 kg in weight if they touch damp soil. -

Delinquent Tax List for 1898

r "'HfSDHfH'1 " "W-1- " mmm mm i"mf imiwpwwp PPlypPlP SUPPLEMENT IF THE HAWAIIAN GAZETTE. VOL. XXXIV. HONOLULU, 11. I., FtiliKUAItY II, 1SD0. SKMMVKKKI.Y. W1I0I.K No. 2010 DELINQUENT TAX LIST FOR 1898 In accordance with Section 58, Act LI , Session Laws of 1896, the following List of Delinquent Taxpayers is hereby published, and comprises the Delinquent Taxes or the FIRST DIVISION AND DISTRICTS, as indicated, including Real Estate, Personal Property, Carriages, Carts and Drays, Dogs and Personal Taxes assessed and remaining unpaid for 1898, with 10 per cent, penalties and the Cost for Advertising, as the Law provides. 102 Clark, Mrs. Jane 30 20 205 Huka, Henry 7 20 309 K.utiaino nnil Kalee 1 60 414 KanlkanllioA (w) .... 4 00 617 Kclllaa, Ester 3 90 103 Cabral, Joaquin 31 15 206 Hlgashl 8 20 .110 Kaulu-a- , II 2 90 415 Kalua No. 2 1 70 618 Kcnu, Kala 13 SS SUPPLEMENT 104 Crulz, John C CS 207 Hoopllllllli 16 55 311 ICalmlhau, Jos 170 41C Kamaliua, loso (w) . 7 10 619 Koohokapu 7 10 105 Corrca, Francisco 2 90 20S Heu, T 13 70 312 Kamaka, 1) 7 20 417 Kahlnu, J. Iocla..... 8 20 520 Kealoha, John 10 95 106 Costa, Maria de 170 209 Hanapau 7 20 313 Katnallc 7 20 418 Kamaka 6 00 C21 Kokoowal, Alona 13 70 TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 14, 1899. 107 Cavanaugh, George C 35 210 Harper, Louisa 25 90 314 Kahale 17 C5 419 Knplloho, C. H 32 00 C22 Koholo (w) 1 co 108 Clark, Charles 7 20 211 Helenlhl, Estato of Jim. -

Micronesica 38(1):93–120, 2005

Micronesica 38(1):93–120, 2005 Archaeological Evidence of a Prehistoric Farming Technique on Guam DARLENE R. MOORE Micronesian Archaeological Research Services P.O. Box 22303, GMF, Guam, 96921 Abstract—On Guam, few archaeological sites with possible agricultural features have been described and little is known about prehistoric culti- vation practices. New information about possible upland planting techniques during the Latte Phase (c. A.D. 1000–1521) of Guam’s Prehistoric Period, which began c. 3,500 years ago, is presented here. Site M201, located in the Manenggon Hills area of Guam’s interior, con- tained three pit features, two that yielded large pieces of coconut shell, bits of introduced calcareous rock, and several large thorns from the roots of yam (Dioscorea) plants. A sample of the coconut shell recovered from one of the pits yielded a calibrated (2 sigma) radiocarbon date with a range of A.D. 986–1210, indicating that the pits were dug during the early Latte Phase. Archaeological evidence and historic literature relat- ing to planting, harvesting, and cooking of roots and tubers on Guam suggest that some of the planting methods used in historic to recent times had been used at Site M201 near the beginning of the Latte Phase, about 1000 years ago. I argue that Site M201 was situated within an inland root/tuber agricultural zone. Introduction The completion of numerous archaeological projects on Guam in recent years has greatly increased our knowledge of the number and types of prehis- toric sites, yet few of these can be considered agricultural. Descriptions of agricultural terraces, planting pits, irrigation canals, or other agricultural earth works are generally absent from archaeological site reports, although it has been proposed that some of the piled rock alignments in northern Guam could be field boundaries (Liston 1996). -

Plant Production--Root Vegetables--Yams Yams

AU.ENCI FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVILOPME4T FOR AID USE ONLY WASHINGTON. 0 C 20823 A. PRIMARYBIBLIOGRAPHIC INPUT SHEET I. SUBJECT Bbliography Z-AFOO-1587-0000 CL ASSI- 8 SECONDARY FICATIDN Food production and nutrition--Plant production--Root vegetables--Yams 2. TITLE AND SUBTITLE A bibliography of yams and the genus Dioscorea 3. AUTHOR(S) Lawani,S.M.; 0dubanjo,M.0. 4. DOCUMENT DATE IS. NUMBER OF PAGES 6. ARC NUMBER 1976 J 199p. ARC 7. REFERENCE ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS IITA 8. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES (Sponaoring Ordanization, Publlahera, Availability) (No annotations) 9. ABSTRACT This bibliography on yams bring together the scattered literature on the genus Dioscorea from the early nineteenth century through 1975. The 1,562 entries in this bibliography are grouped into 36 subject categories, and arranged within each category alphabetically by author. Some entries, particularly those whose titles are not sufficiently informative, are annotated. The major section titles in the book are as follows: general and reference works; history and eography; social and cultural importance; production and economics; botany including taxonomy, genetics, and breeding); yam growing (including fertilizers and plant nutrition); pests and diseases; storage; processing; chemical composition, nutritive value, and utilization; toxic and pharmacologically active constituents; author index; and subject index. Most entries are in English, with a few in French, Spanish, or German. 10. CONTROL NUMBER I1. PRICE OF DOCUMENT PN-AAC-745 IT. DrSCRIPTORS 13. PROJECT NUMBER Sweet potatoes Yams 14. CONTRACT NUMBER AID/ta-G-1251 GTS 15. TYPE OF DOCUMENT AID 590-1 44-741 A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF YAMS AND THE GENUS DIOSCOREA by S. -

The Hawaiian Islands Case Study Robert F

FEATURE Origin of Horticulture in Southeast Asia and the Dispersal of Domesticated Plants to the Pacific Islands by Polynesian Voyagers: The Hawaiian Islands Case Study Robert F. Bevacqua1 Honolulu Botanical Gardens, 50 North Vineyard Boulevard, Honolulu, HI 96817 In the islands of Southeast Asia, following the valleys of the Euphrates, Tigris, and Nile tuber, and fruit crops, such as taro, yams, the Pleistocene or Ice ages, the ancestors of the rivers—and that the first horticultural crops banana, and breadfruit. Polynesians began voyages of exploration into were figs, dates, grapes, olives, lettuce, on- Chang (1976) speculates that the first hor- the Pacific Ocean (Fig. 1) that resulted in the ions, cucumbers, and melons (Halfacre and ticulturists were fishers and gatherers who settlement of the Hawaiian Islands in A.D. 300 Barden, 1979; Janick, 1979). The Greek, Ro- inhabited estuaries in tropical Southeast Asia. (Bellwood, 1987; Finney, 1979; Irwin, 1992; man, and European civilizations refined plant They lived sedentary lives and had mastered Jennings, 1979; Kirch, 1985). These skilled cultivation until it evolved into the discipline the use of canoes. The surrounding terrestrial mariners were also expert horticulturists, who we recognize as horticulture today (Halfacre environment contained a diverse flora that carried aboard their canoes many domesti- and Barden, 1979; Janick, 1979). enabled the fishers to become intimately fa- cated plants that would have a dramatic impact An opposing view associates the begin- miliar with a wide range of plant resources. on the natural environment of the Hawaiian ning of horticulture with early Chinese civili- The first plants to be domesticated were not Islands and other areas of the world. -

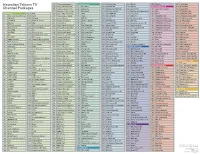

SPECTRUM TV PACKAGES Kona | November 2019

SPECTRUM TV PACKAGES Kona | November 2019 TV PACKAGES 24 SundanceTV 660 Starz Comedy - W 26 TBN SPECTRUM TV SILVER Showtime STARZ ENCORE SPECTRUM BASIC 32 SonLife 633 Showtime - W 33 TNT (Includes Spectrum TV Select 634 SHO 2 - W 666 StarzEncore - W (Includes Digital Music channels 34 AMC and the following channels) 635 Showtime Showcase-W 667 StarzEncore Action - W and the following services) 39 Galavisión 636 SHO Extreme - W 668 StarzEncore Classic-W Digi Tier 1 2 KBFD - IND 40 Hallmark Mov. & Myst. 637 SHO Beyond - W 669 StarzEncore Susp-W 3 KHON - FOX 43 msnbc 23 Disney Junior 638 SHO Next - W 670 StarzEncore Black-W 4 KITV - ABC 44 CNBC 24 SundanceTV 640 Showtime Fam Zn-W 671 StarzEncore Wstns-W 5 KHII - MyTV 48 A&E 35 Univisión 1636 SHO Extreme - E 672 StarzEncore Fam-W 6 KSIX - Telemundo 49 BBC America 36 El Rey Network 1637 SHO Beyond - E 7 KGMB - CBS 51 CNN 37 Fuse 1639 SHO Women - E MULTICULTURAL 8 KHNL - NBC 52 HLN 41 Cooking Channel CHANNELS 9 KIKU - IND 57 Disney Channel 42 BBC World News SPECTRUM TV GOLD 10 KHET - PBS 58 Food Network 74 TVK2 LATINO VIEW 11 KWHE - LeSea 59 HGTV 75 TVK24 (Includes Spectrum TV Silver and 16 Spectrum OC16 60 WGN America 76 MYX TV the following channels) 35 Univisión 17 Spectrum XCast 61 TBS 77 Mnet 36 El Rey Network 18 Spectrum XCast 2 63 TLC 110 Newsmax TV Digi Tier 2 38 FOROtv 19 Spectrum XCast Multiview 64 Oxygen 120 Cheddar Business 117 CNBC 229 BeIN SPORTS 20 Spectrum Surf Channel 65 truTV 123 i24 117 CNBC World 570 Tr3s 22 KHNL - IND 66 WE tv 125 Heroes & Icons 203 NFL Network 573 WAPA -

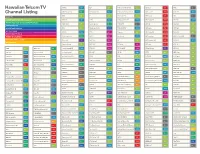

Hawaiian Telcom TV Channel Packages

Hawaiian Telcom TV 604 Stingray Everything 80’s ADVANTAGE PLUS 1003 FOX-KHON HD 1208 BET HD 1712 Pets.TV 525 Thriller Max 605 Stingray Nothin but 90’s 21 NHK World 1004 ABC-KITV HD 1209 VH1 HD MOVIE VARIETY PACK 526 Movie MAX Channel Packages 606 Stingray Jukebox Oldies 22 Arirang TV 1005 KFVE (Independent) HD 1226 Lifetime HD 380 Sony Movie Channel 527 Latino MAX 607 Stingray Groove (Disco & Funk) 23 KBS World 1006 KBFD (Korean) HD 1227 Lifetime Movie Network HD 381 EPIX 1401 STARZ (East) HD ADVANTAGE 125 TNT 608 Stingray Maximum Party 24 TVK1 1007 CBS-KGMB HD 1229 Oxygen HD 382 EPIX 2 1402 STARZ (West) HD 1 Video On Demand Previews 126 truTV 609 Stingray Dance Clubbin’ 25 TVK2 1008 NBC-KHNL HD 1230 WE tv HD 387 STARZ ENCORE 1405 STARZ Kids & Family HD 2 CW-KHON 127 TV Land 610 Stingray The Spa 28 NTD TV 1009 QVC HD 1231 Food Network HD 388 STARZ ENCORE Black 1407 STARZ Comedy HD 3 FOX-KHON 128 Hallmark Channel 611 Stingray Classic Rock 29 MYX TV (Filipino) 1011 PBS-KHET HD 1232 HGTV HD 389 STARZ ENCORE Suspense 1409 STARZ Edge HD 4 ABC-KITV 129 A&E 612 Stingray Rock 30 Mnet 1017 Jewelry TV HD 1233 Destination America HD 390 STARZ ENCORE Family 1451 Showtime HD 5 KFVE (Independent) 130 National Geographic Channel 613 Stingray Alt Rock Classics 31 PAC-12 National 1027 KPXO ION HD 1234 DIY Network HD 391 STARZ ENCORE Action 1452 Showtime East HD 6 KBFD (Korean) 131 Discovery Channel 614 Stingray Rock Alternative 32 PAC-12 Arizona 1069 TWC SportsNet HD 1235 Cooking Channel HD 392 STARZ ENCORE Classic 1453 Showtime - SHO2 HD 7 CBS-KGMB 132 -

Hawaiian Telcom TV Channel Listing

Hawaiian Telcom TV CMT HD 1200 DIY 234 FOX Sports Prime Ticket 82 HBO East 501 KFVE 13 Channel Listing CMT Pure Country 201 DIY Network HD 1234 FOX Sports Prime Ticket HD 1082 HBO East HD 1501 KFVE HD* 1013 CNBC 176 E! 240 FOX Sports West 81 HBO Family 507 KHII 5 BASIC TV ADVANTAGE (INCLUDES BASIC TV) CNBC HD 1176 E! HD 1240 FOX Sports West HD 1081 HBO Family HD 1507 KHII HD* 1005 ADVANTAGE PLUS (INCLUDES ADVANTAGE) CNBC World 177 Eleven Sports 91 FOX-KHON 3 HBO HD 1502 KHJZ 93.9 665 ADVANTAGE HD ADVANTAGE PLUS HD CNN 172 Eleven Sports HD 1091 FOX-KHON HD* 1003 HBO Latino 512 KHPR 88.1 661 HD PLUS PACK *HD SERVICE WITH BASIC TV PACK includes these channels. CNN HD 1172 EPIX 381 Freeform 122 HBO Latino HD 1512 Kid’s Stuff 627 MOVIE VARIETY PACK CNN International 304 EPIX 2 382 Freeform HD 1122 HBO Signature 505 KIKU-TV (Jpn/UPN) 20 PREMIUM CHANNELS INTERNATIONAL / OTHER Comedy.TV 1707 EPIX 2 HD 1382 FX 124 HBO Signature HD 1505 KIKU HD* 1020 PAY PER VIEW Comedy Central 142 EPIX 3 HD 1383 FX Movie 398 HBO Zone 511 KINE 105.1 675 A&E 129 BET Soul 211 Comedy Central HD 1142 EPIX HD 1381 FX Movie HD 1398 HDNet Movies 1703 KIPO 89.3 662 A&E HD 1129 Big Ten Network 79 Cooking Channel 235 ESCAPE 46 FX HD 1124 HGTV 232 KKEA 1420 678 ABC-KITV 4 Big Ten Network HD 1079 Cooking Channel HD 1235 ESPN 70 FXX 110 HGTV HD 1232 KORL 101.1 672 ABC-KITV HD* 1004 Bloomberg TV 171 COZI 15 ESPN Classic Sports 71 FXX HD 1110 History Channel 133 KPHW 104.3 674 Action Max 523 Bloomberg TV HD 1171 Crime & Investigation 303 ESPN HD 1070 FYI 300 History Channel HD -

And Then There Were None Unit Plan 2 (Grades 6-12: Focus on High School)

And Then There Were None Unit Plan 2 (Grades 6-12: Focus on High School) Unit Plan for grades 6-12: The required Modern Hawaiian History course generally taken at grade 9 or 10 is founded upon Social Studies standards are focused on Hawaiian history from the end of the monarchy period through modern times. Modern Hawaiian History benchmarks, therefore, contain content related to the period of the Overthrow, the Hawaiian Territorial government, and eventually statehood. Therefore, the grade 7 Hawaiian Monarchy course provides a foundation for the era studied at the high school level. The standards, which are more general, listed below can be used as guidance for grade levels other than grade 10. Specific benchmarks are listed for grade 10 since its focus is Hawaiian history. All of Hawaii’s Content and Performance Standards can be viewed through the Hawaii Department of Education website at www.doe.k12.hi.us. The essential question that follows can be used to guide a unit of study lasting approximately 3 weeks in a social studies class. The objectives and activities listed can be used as guides to lesson plans. Hawaii Content and Performance Standards Gr 6-12 Standards Social Studies Standard 1: Historical Understanding: CHANGE, CONTINUITY, AND CAUSALITY- Understand change and/or continuity and cause and/or effect in history Social Studies Standard 2: Historical Understanding: INQUIRY, EMPATHY AND PERSPECTIVE- Use the tools and methods of inquiry, perspective, and empathy to explain historical events with multiple interpretations and judge -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C.