Referentiality and the Films of Woody Allen This Page Intentionally Left Blank Referentiality and the Films of Woody Allen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen

False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen by Nicholas Vick November, 2012 Director of Thesis: Amanda Klein Major Department: English Woody Allen is an auteur who is deeply concerned with the visual presentation of his cityscapes. However, each city that Allen films is presented in such a glamorous light that the depiction of the cities is falsely authentic. That is, Allen's cityscapes are actually unrealistic recreations based on his nostalgia or stilted view of the city's culture. Allen's treatment of each city is similar to each other in that he strives to create a cinematic postcard for the viewer. However, differing themes and characteristics emerge to define Allen's optimistic visual approach. Allen's hometown of Manhattan is a place where artists, intellectuals, and writers can thrive. Paris denotes a sense of nostalgia and questions the power behind it. Allen's London is primarily concerned with class and the social imperative. Finally, Barcelona is a haven for physicality, bravado, and sex but also uncertainty for American travelers. Despite being in these picturesque and dynamic locations, happiness is rarely achieved for Allen's characters. So, regardless of Allen's dreamy and romanticized visual treatment of cityscapes and culture, Allen is a director who operates in a continuous state of contradiction because of the emotional unrest his characters suffer. False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen A Thesis Presented To the Faculty of the Department of English East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MA English by Nicholas Vick November, 2012 © Nicholas Vick, 2012 False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen by Nicholas Vick APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF DISSERTATION/THESIS: _______________________________________________________ Dr. -

COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media Humor and the Documentary The Four Humor Mechanisms (Neuendorf & Skalski et al.; see also the extended handout on the class web site) 1. Disparagement: Focusing on a perception of superiority, a one-up/one-down relationship, e.g., “putdown” humor, satire, sarcasm, self-deprecation, and the display of stupid behaviors (Freud, 1960; Hobbes, 1651/1981) 2. Incongruity: The juxtaposition of inconsistent or incongruous elements, e.g., wordplay (e.g., puns), “pure” incongruity, absurdity, and sight gags (Schopenhauer in Martin, 2007; Koestler, 1964). 3. Arousal/Dark: The creation of a high level of physiological arousal, e.g., slapstick, dark humor, sick humor, and sexual or naughty humor (Kant & Spencer; Spencer, 1860; Berlyne, 1972). 4. Social currency: Playful interaction, or building a sense of group belonging or understanding, e.g., joking to fit in, joking around socially, inside jokes, and parody (relying on a shared view of a known form, such as a film genre) (Chapman, 1983; Fry, 1963). Satire vs. Parody Parody deals with literary/cinematic norms (at the level of the cultural product) Satire deals with social/political norms (at the level of the culture or society) There is sometimes confusion between the two, perhaps because they may be used together (e.g., Western movie parody + satire on racism = Blazing Saddles) Four Stages of Genre Development (Giannetti and others) 1. Primitive 2. Classical 3. Revisionist 4. Parodic 2 Humor and Documentaries: 1. [Social] Satire -

TAKE the MONEY and RUN Woody Allen, 1969

TAKE THE MONEY AND RUN Woody Allen, 1969 TRANSCRIPT NARRATOR On December 1st, 1935, Mrs. Williams Starkwell, the wife of a New Jersey handyman, gives birth to her first and only child. It is a boy, and they name it Virgil. He is an exceptionally cute baby, with a sweet disposition. Before he is 25 years old, he will be wanted by police in six states, for assault, armed robbery, and illegal possession of a wart. Growing up in a slum neighbourhood where the crime rate is amongst the highest in the nation is not easy. Particularly for Virgil, who is small and frail compared to the other children. Virgil Starkwell attends this school, where he scores well on an IQ test, although his behaviour disturbs the teachers. We interviewed Mrs. Dorothy Lowry, a school teacher who remembers Virgil. DOROTHY LOWRY I remember one time, he stole a fountain pen. I didn't want to embarrass him. You know teachers have ways of doing things. So I said to the class. We will all close our eyes, and will the one who took the pen, please return it. Well, while our eyes were closed, he returned the pen. But he took the opportunity of feeling all the girls! Can I say feel? NARRATOR Spending most of his time in the streets, Virgil takes to crime at an early age. He is an immediate failure. He barely manages to escape with a gumball machine stuck on his hand. With both parents working to make ends meet, Virgil becomes closest to his grandfather, a 60-year-old German immigrant who takes the boy to movies and baseball games. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell information Company 300 Nortti Zeeb Road Ann Arbor Ml 48106-1346 USA 313 761-4700 800 521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Funny Feelings: Taking Love to the Cinema with Woody Allen

FUNNY FEELINGS: TAKING LOVE TO THE CINEMA WITH WOODY ALLEN by Zorianna Ulana Zurba Combined Bachelor of Arts Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, 2004 Masters of Arts Brock University, St. Catherines, Ontario, 2008 Certificate University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, 2009 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture. Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2015 ©Zorianna Zurba 2015 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University and York University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research I further authorize Ryerson University and York University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Funny Feelings: Taking Love to the Cinema with Woody Allen Zorianna Zurba, 2015 Doctor of Philosophy in Communication and Culture Ryerson University and York University Abstract This dissertation utilizes the films of Woody Allen in order to position the cinema as a site where realizing and practicing an embodied experience of love is possible. This dissertation challenges pessimistic readings of Woody Allen’s film that render love difficult, if not impossible. By challenging assumptions about love, this dissertation opens a dialogue not only about the representation of love, but the understanding of love. -

A Film by Woody Allen Javier Bardem Patricia Clarkson Penélope Cruz

A film by Woody Allen Javier Bardem Patricia Clarkson Penélope Cruz Kevin Dunn Rebecca Hall Scarlett Johansson Chris Messina Official Selection – 2008 Cannes Film Festival Release Date: 26 December 2008 Running Time: 96 mins Rated: TBC For more information contact Jillian Heggie at Hopscotch Films on 02 8303 3800 or at [email protected] VICKY CRISTINA BARCELONA Starring (in alphabetical order) Juan Antonio JAVIER BARDEM Judy Nash PATRICIA CLARKSON Maria Elena PENÉLOPE CRUZ Mark Nash KEVIN DUNN Vicky REBECCA HALL Cristina SCARLETT JOHANSSON Doug CHRIS MESSINA Co-Starring (in alphabetical order) ZAK ORTH CARRIE PRESTON PABLO SCHREIBER Filmmakers Writer/Director WOODY ALLEN Producers LETTY ARONSON GARETH WILEY STEPHEN TENENBAUM Co-Producers HELEN ROBIN Executive Producer JAUME ROURES Co-Executive Producers JACK ROLLINS CHARLES H. JOFFE JAVIER MÉNDEZ Director of Photography JAVIER AGUIRRESAROBE Production Designer ALAIN BAINÉE Editor ALISA LEPSELTER Costume Designer SONIA GRANDE Casting JULIET TAYLOR & PATRICIA DiCERTO Additional Spanish Casting PEP ARMENGOL & LUCI LENOX * * * 2 VICKY CRISTINA BARCELONA Synopsis Woody Allen’s breezy new romantic comedy is about two young American women and their amorous escapades in Barcelona, one of the most romantic cities in the world. Vicky (Rebecca Hall) and Cristina (Scarlett Johansson) are best friends, but have completely different attitudes towards love. Vicky is sensible and engaged to a respectable young man. Cristina is sexually and emotionally uninhibited, perpetually searching for a passion that will sweep her off her feet. When Judy (Patricia Clarkson) and Mark (Kevin Dunn), distant relatives of Vicky, offer to host them for a summer in Barcelona, the two of them eagerly accept: Vicky wants to spend her last months as a single woman doing research for her Masters, and Cristina is looking for a change of scenery to flee the psychic wreckage of her last breakup. -

A Film by Woody Allen

Persmap - Ampèrestraat 10 - 1221 GJ Hilversum - T: 035-6463046 - F: 035-6463040 - email: [email protected] A film by Woody Allen Spanje · 2008 · 35mm · color · 96 min. · Dolby Digital · 1:1.85 Vicky en Cristina zijn twee hartsvriendinnen met tegengestelde karakters. Vicky is de verstandige en verloofd met een degelijke jongeman, Cristina daarentegen laat zich leiden door haar gevoelens en is voortdurend op zoek naar nieuwe passies en seksuele ervaringen. Wanneer ze de kans krijgen om de zomer in Barcelona door te brengen, zijn ze allebei dolenthousiast : Vicky wil nog voor haar huwelijk een master behalen, terwijl Cristina na haar laatste liefdesperikelen behoefte heeft aan iets nieuws. Op een avond ontmoeten ze in een kunstgalerij een Spaanse schilder. Juan Antonio is knap, sensueel en verleidelijk en doet hen een nogal ongewoon voorstel… Maar deze nieuwe vriendschap valt niet in de smaak van Juan Antonio’s ex-vriendin. www.vickycristina-movie.com Officiële Selectie – 2008 Cannes Film Festival Genre: drama Release datum: 11 december 2008 Distributie: cinéart Meer informatie: Publiciteit & Marketing: cinéart Noor Pelser & Janneke De Jong Ampèrestraat 10, 1221 GJ Hilversum Tel: +31 (0)35 6463046 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Persmappen en foto’s staan op: www.cineart.nl Persrubriek inlog: cineart / wachtwoord: film - Ampèrestraat 10 - 1221 GJ Hilversum - T: 035-6463046 - F: 035-6463040 - email: [email protected] Starring (in alphabetical order) Juan Antonio JAVIER BARDEM Judy Nash PATRICIA CLARKSON Maria Elena PENÉLOPE CRUZ Mark Nash KEVIN DUNN Vicky REBECCA HALL Cristina SCARLETT JOHANSSON Doug CHRIS MESSINA Co-Starring (in alphabetical order) ZAK ORTH CARRIE PRESTON PABLO SCHREIBER Filmmakers Writer/Director WOODY ALLEN Producers LETTY ARONSON GARETH WILEY STEPHEN TENENBAUM Co-Producers HELEN ROBIN Executive Producer JAUME ROURES Co-Executive Producers JACK ROLLINS CHARLES H. -

ICE - Making Predictions

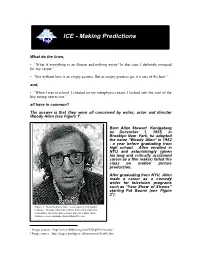

A ICE - Making Predictions What do the lines, • “What if everything is an illusion and nothing exists? In that case, I definitely overpaid for my carpet.” • “Sex without love is an empty gesture. But as empty gestures go, it is one of the best.” and, • “When I was in school, I cheated on my metaphysics exam: I looked into the soul of the boy sitting next to me.” all have in common? The answer is that they were all conceived by writer, actor and director Woody Allen (see Figure 11. Born Allan Stewart Konigsberg on December 1, 1935, in Brooklyn New York, he adopted the name “Woody Allen” in 1952 - a year before graduating from high school. Allen enrolled in NYU and astonishingly (given his long and critically acclaimed career as a film maker) failed the class on motion picture production. After graduating from NYU, Allen made a career as a comedy writer for television programs such as “Your Show of Shows” starring Pat Boone (see Figure 22). Figure 1: Described as a “pale, bespectacled, 120 pound neurotic,” Woody Allen has written, directed or starred in (sometimes all of the above) more than 40 feature films during a career spanning almost than 40 years. 1 Image source: http://www.ibiblio.org/mal/MO/phlim/woody/ 2 Image source: http://pages.prodigy.net/dianamorris/feat1k.htm Allen made his first professional appearance as a comedian in 1960, and between 1964 and 1965 released three comedy albums that were enthusiastically received. Also in 1965, Allen’s first motion picture “What’s New, Pussycat” was released. -

Woody Loves Ingmar

1 Woody loves Ingmar Now that, with Blue Jasmine , Woody Allen has come out … … perhaps it’s time to dissect all his previous virtuoso creative adapting. I’m not going to write about the relationship between Vicky Christina Barcelona and Jules et Jim . ————— Somewhere near the start of Annie Hall , Diane Keaton turns up late for a date at the cinema with Woody Allen, and they miss the credits. He says that, being anal, he has to see a film right through from the very start to the final finish, so it’s no go for that movie – why don’t they go see The Sorrow and the Pity down the road? She objects that the credits would be in Swedish and therefore incomprehensible, but he remains obdurate, so off they go, even though The Sorrow and the Pity is, at over four hours, twice the length of the film they would have seen. 2 The film they would have seen is Ingmar Bergman’s Face to Face , with Liv Ullmann as the mentally-disturbed psychiatrist – you see the poster behind them as they argue. The whole scene is a gesture. Your attention is being drawn to an influence even while that influence is being denied: for, though I don’t believe Bergman has seen too much Allen, Allen has watched all the Bergman there is, several times over. As an example: you don’t often hear Allen’s early comedy Bananas being referred to as Bergman-influenced: but not only does its deranged Fidel Castro-figure proclaim that from now on the official language of the revolutionised country will be Swedish, but in the first reel there’s a straight Bergman parody. -

Religion, God and the Meaninglessness of It All in Woody Allen’S Thought and Films

Religion, God and the Meaninglessness of it all in Woody Allen’s Thought and Films “I just wanted to illustrate, in an entertaining way, that there is no God.” (Woody Allen on Crimes and Misdemeanors)1 Johanna Petsche In his films dating from 1975 to 1989 Woody Allen rigorously explores themes of religion, God, morality and death as he compulsively examines and questions his atheistic outlook. At the core of these films lies Allen’s existential dilemma in which his intellectual tendency towards atheism conflicts with his emotional need for meaning, objective moral values and justice, all of which he strongly associates with the existence of God. There will be an analysis of Allen’s treatment of religious and existential themes in Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) and Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989), with a focus on the various ways that he portrays his existential dilemma. Allen absorbs and integrates into his films an assortment of philosophical ideas and biblical themes. References will be made to Camus, Kierkegaard, Wittgenstein and Kant, and to passages from Genesis, the Book of Job, Ecclesiastes and the Book of Jeremiah. First however it is necessary to consider Allen’s Jewish background as, despite his protestations to the contrary, it clearly plays a significant role in his life and films. Born Allan Stewart Konigsberg in 1935, Allen was raised in a middle-class Jewish community in Flatbush, Brooklyn. For at least part of his childhood his family spoke Yiddish, “a convenient secret language, rich in terms of irony and scepticism, and as such central to Jewish humour”.2 Allen’s parents are of European Jewish descent and although they were born and raised on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, their lives were always dominated by the shtetl their parents fled but whose ways they continued to embrace.3 Allen attended both synagogue and Hebrew school until he was bar mitzvahed at the age of thirteen, but by twenty had anglicised his name and completely disengaged from the Jewish faith. -

Film 484: Film Directors/Woody Allen

Film 484: Film Directors/Woody Allen “You got to remember that Woody Allen is a writer…. It can be argued that he is America’s greatest writer.” —Jonathan Schwartz, WNYC Prof. Christopher Knight Autumn 2015 Department of English Office: LA 115 Tel.: 243-2878 Email: [email protected] Class Meeting: Tuesday & Thursday, 9:40 - 12 Office Hours: Wednesday & Friday, 10 – 11; and by appointment Library Films & Texts on Reserve: Each of the films is on two-hour reserve at the Mansfield Library’s front desk. Also on reserve are the following books: 1. Peter Bailey, The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen. University of Kentucky Press, 2001. 2. Peter Bailey & Sam Girgus, eds., A Companion to Woody Allen, Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. 3. Sam Girgus, The Films of Woody Allen, Cambridge University Press, 1993. 4. Eric Lax, Conversations with Woody Allen: His Films, The Movies, and Moviemaking. Alfred A. Knopf, 2009. 5. Charles L. P. Silet, ed., The Films of Woody Allen: Critical Essays, Scarescrow Press, 2006. Plan: Woody Allen began his career as a gag writer; moved to doing stand-up comedy; then began writing film scripts, short fiction and plays. His first work as a director came in 1966, with What’s Up, Tiger Lily? His next efforts in directing—including Take the Money and Run (1969), Bananas (1971), Everything You Wanted to Know About Sex (1972), Sleeper (1973) and Love and Death (1975)—carried forward his work as a comedian in the tradition of Charlie Chaplin and Groucho Marx. In 1977 came Annie Hall, a film that Graham McCann has spoken of as “a watershed,” for the reason that with this film Allen introduces an intellectual, emotional and narrative complexity that had shown itself less crucial in his earlier films, with the possible exception of Play It Again, Sam, a Harold Ross directed film based upon Allen’s Broadway play of the same name, and starring Allen, Tony Roberts and Diane Keaton, the three of whom would be reunited in Annie Hall.