Ichthyological Differentiation and Homogenization in the Pánuco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Tale of Two Herichthys

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 209(1): 1-18 LIVE COLOR PATTERNS DIAGNOSE SPECIES: A TALE OF TWO HERICHTHYS By RONALD G. OLDFIELD1,2, ABHINAV KAKUTURU1, 2 3 4 WILLIAM I. LUTTERSCHMIDT , O. TOM LORENZ , ADAM E. COHEN , AND DEAN A. HENDRICKSON4 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Museum of Zoology University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109–1079, USA Ann Arbor, April 27, 2021 ISSN 0076-8406 JOHN LUNDBERG1, EDITOR GERALD SMITH2, EDITOR MACKENZIE SCHONDELMAYER2, COMPOSITOR 1Department of Ichthyology, The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA 19103 2Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48197 LIVE COLOR PATTERNS DIAGNOSE SPECIES: A TALE OF TWO HERICHTHYS By RONALD G. OLDFIELD1,2, ABHINAV KAKUTURU1, WILLIAM I. LUTTERSCHMIDT2, O. TOM LORENZ3, ADAM E. COHEN4, AND DEAN A. HENDRICKSON4 ABSTRACT The Rio Grande Cichlid, Herichthys cyanoguttatus, is native to the drainages of the Gulf Coast of northern Mexico and southern Texas and has been introduced at several sites in the US. Previous observations have suggested that non-native populations in Louisiana that are currently recognized as H. cyanoguttatus resemble another species, the Lowland Cichlid, H. carpintis. Traditional morphological and genetic techniques have been insufficient to differentiate these species, but H. carpintis has been reported to differ fromH. cyanoguttatus in color pattern, so we turned to novel electronic photo archives to determine the identity of the species introduced in Louisiana. First, we used the public databases Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database and Fishes of Texas to infer the historical distributions of these species in the US. -

Article Evolutionary Dynamics of the OR Gene Repertoire in Teleost Fishes

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.09.434524; this version posted March 10, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Article Evolutionary dynamics of the OR gene repertoire in teleost fishes: evidence of an association with changes in olfactory epithelium shape Maxime Policarpo1, Katherine E Bemis2, James C Tyler3, Cushla J Metcalfe4, Patrick Laurenti5, Jean-Christophe Sandoz1, Sylvie Rétaux6 and Didier Casane*,1,7 1 Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS, IRD, UMR Évolution, Génomes, Comportement et Écologie, 91198, Gif-sur-Yvette, France. 2 NOAA National Systematics Laboratory, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20560, U.S.A. 3Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 20560, U.S.A. 4 Independent Researcher, PO Box 21, Nambour QLD 4560, Australia. 5 Université de Paris, Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire des Energies de Demain, Paris, France 6 Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS, Institut des Neurosciences Paris-Saclay, 91190, Gif-sur- Yvette, France. 7 Université de Paris, UFR Sciences du Vivant, F-75013 Paris, France. * Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected]. !1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.09.434524; this version posted March 10, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Teleost fishes perceive their environment through a range of sensory modalities, among which olfaction often plays an important role. -

Female Choice Undermines the Emergence of Strong Sexual Isolation Between Locally Adapted Populations of Atlantic Mollies (Poecilia Mexicana)

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Female Choice Undermines the Emergence of Strong Sexual Isolation between Locally Adapted Populations of Atlantic Mollies (Poecilia mexicana) Claudia Zimmer 1,2,*, Rüdiger Riesch 3 ID , Jonas Jourdan 4 ID , David Bierbach 5, Lenin Arias-Rodriguez 6 and Martin Plath 1,7 1 College of Animal Science & Technology, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Ecology and Evolution, Goethe University of Frankfurt, Max-von-Laue-Straße 13, D-60438 Frankfurt am Main, Germany 3 Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Behaviour, School of Biological Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK; [email protected] 4 Department of River Ecology and Conservation, Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt, D-63571 Gelnhausen, Germany; [email protected] 5 Department of Biology and Ecology of Fishes, Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Müggelseedamm 310, D-12587 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] 6 División Académica de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco (UJAT), 86150 Villahermosa, Tabasco, Mexico; [email protected] 7 Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Molecular Biology for Agriculture, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 24 January 2018; Accepted: 25 April 2018; Published: 2 May 2018 Abstract: Divergent selection between ecologically dissimilar habitats promotes local adaptation, which can lead to reproductive isolation (RI). Populations in the Poecilia mexicana species complex have independently adapted to toxic hydrogen sulfide and show varying degrees of RI. Here, we examined the variation in the mate choice component of prezygotic RI. -

Morphological and Genetic Comparative

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 79: 373- 383, 2008 Morphological and genetic comparative analyses of populations of Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Cyprinodontiformes:Goodeidae) from Central Mexico, with description of a new species Análisis comparativo morfológico y genético de diferentes poblaciones de Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Cyprinodontiformes:Goodeidae) del Centro de México, con la descripción de una especie nueva Domínguez-Domínguez Omar1*, Pérez-Rodríguez Rodolfo1 and Doadrio Ignacio2 1Laboratorio de Biología Acuática, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Fuente de las Rosas 65, Fraccionamiento Fuentes de Morelia, 58088 Morelia, Michoacán, México 2Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, España. *Correspondent: [email protected] Abstract. A genetic and morphometric study of populations of Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Bean, 1898) from the Lerma and Ameca basins and Cuitzeo, Zacapu and Chapala Lakes in Central Mexico was conducted. For the genetic analysis, 7 populations were sampled and 2 monophyletic groups were identifi ed with a genetic difference of DHKY= 3.4% (3-3.8%), one being the populations from the lower Lerma basin, Ameca and Chapala Lake, and the other populations from Zacapu and Cuitzeo Lakes. For the morphometric analysis, 4 populations were sampled and 2 morphotypes identifi ed, 1 from La Luz Spring in the lower Lerma basin and the other from Zacapu and Cuitzeo Lakes drainages. Using these 2 sources of evidence, the population from La Luz is regarded as a new species Zoogoneticus purhepechus sp. nov. _The new species differs from its sister species Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis_ in having a shorter preorbital distance (Prol/SL x = 0.056, SD = 0.01), longer dorsal fi n base length (DFL/SL x = 0.18, SD = 0.03) and 13-14 rays in the dorsal fi n. -

The Evolution of the Placenta Drives a Shift in Sexual Selection in Livebearing Fish

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature13451 The evolution of the placenta drives a shift in sexual selection in livebearing fish B. J. A. Pollux1,2, R. W. Meredith1,3, M. S. Springer1, T. Garland1 & D. N. Reznick1 The evolution of the placenta from a non-placental ancestor causes a species produce large, ‘costly’ (that is, fully provisioned) eggs5,6, gaining shift of maternal investment from pre- to post-fertilization, creating most reproductive benefits by carefully selecting suitable mates based a venue for parent–offspring conflicts during pregnancy1–4. Theory on phenotype or behaviour2. These females, however, run the risk of mat- predicts that the rise of these conflicts should drive a shift from a ing with genetically inferior (for example, closely related or dishonestly reliance on pre-copulatory female mate choice to polyandry in conjunc- signalling) males, because genetically incompatible males are generally tion with post-zygotic mechanisms of sexual selection2. This hypoth- not discernable at the phenotypic level10. Placental females may reduce esis has not yet been empirically tested. Here we apply comparative these risks by producing tiny, inexpensive eggs and creating large mixed- methods to test a key prediction of this hypothesis, which is that the paternity litters by mating with multiple males. They may then rely on evolution of placentation is associated with reduced pre-copulatory the expression of the paternal genomes to induce differential patterns of female mate choice. We exploit a unique quality of the livebearing fish post-zygotic maternal investment among the embryos and, in extreme family Poeciliidae: placentas have repeatedly evolved or been lost, cases, divert resources from genetically defective (incompatible) to viable creating diversity among closely related lineages in the presence or embryos1–4,6,11. -

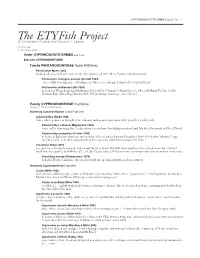

The Etyfish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J

CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3) · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 3.0 - 13 Nov. 2020 Order CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3 of 4) Suborder CYPRINODONTOIDEI Family PANTANODONTIDAE Spine Killifishes Pantanodon Myers 1955 pan(tos), all; ano-, without; odon, tooth, referring to lack of teeth in P. podoxys (=stuhlmanni) Pantanodon madagascariensis (Arnoult 1963) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Madagascar, where it is endemic [extinct due to habitat loss] Pantanodon stuhlmanni (Ahl 1924) in honor of Franz Ludwig Stuhlmann (1863-1928), German Colonial Service, who, with Emin Pascha, led the German East Africa Expedition (1889-1892), during which type was collected Family CYPRINODONTIDAE Pupfishes 10 genera · 112 species/subspecies Subfamily Cubanichthyinae Island Pupfishes Cubanichthys Hubbs 1926 Cuba, where genus was thought to be endemic until generic placement of C. pengelleyi; ichthys, fish Cubanichthys cubensis (Eigenmann 1903) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Cuba, where it is endemic (including mainland and Isla de la Juventud, or Isle of Pines) Cubanichthys pengelleyi (Fowler 1939) in honor of Jamaican physician and medical officer Charles Edward Pengelley (1888-1966), who “obtained” type specimens and “sent interesting details of his experience with them as aquarium fishes” Yssolebias Huber 2012 yssos, javelin, referring to elongate and narrow dorsal and anal fins with sharp borders; lebias, Greek name for a kind of small fish, first applied to killifishes (“Les Lebias”) by Cuvier (1816) and now a -

Oocyte Structure and Ultrastructure in the Mexican Silverside Fish Chirostoma Humboldtianum (Atheriniformes: Atherinopsidae)

Oocyte structure and ultrastructure in the Mexican silverside fish Chirostoma humboldtianum (Atheriniformes: Atherinopsidae) Rodolfo Cárdenas1, Mónica Chávez1, José Luis González1, Patricia Aley2, Jesús Espinosa2 & Luis Felipe Jiménez-García3 1. Laboratorio de Endocrinología de Peces, Unidad de Morfología y Función, F.E.S.-Iztacala, U.N.A.M.; rodolf@servi- dor.unam.mx 2. Laboratorio de Neuromorfología, U.I.I.C.S.E., F.E.S.-Iztacala, U.N.A.M. 3. Laboratorio de Microscopia Confocal, Facultad de Ciencias, U.N.A.M. Received 11-VII-2007. Corrected 30-VI-2008. Accepted 31-VII-2008. Abstract: the structural and ultrastructural features of gonads from endemic Mexican fish have received scarce attention. This study describes the histological and ultrastructural characteristics of the oocyte in Chirostoma humboldtianum. The ovary is asynchronic, and as such, most phases of oocyte development are found in the same ovary. The complete process of oogenesis was divided in five stages: oogonium and folliculogenesis, pri- mary growth, cortical alveoli and lipid inclusions, vitellogenesis and maturation. The presence of big filaments, which appear at the end of primary growth, induces some common follicular adaptation. During primary growth, abundant ribosomes, rough endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria are grouped in the cytoplasm. At the end of this stage, the Z1 layer of the chorion is developed, while microvilli start to be evident as well. In the corti- cal alveoli and lipid droplets phase, intense PAS positive vesicles, some of them containing nucleoid material, are observed in the peripheral cytoplasm and the lipid droplets take a more central position. In vitellogenesis, the proteic yolk accumulates in a centripetal way while the chorion is completely formed. -

Butterfly Splitfin (Ameca Splendens) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Butterfly Splitfin (Ameca splendens) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, January 2013 Revised, January 2018 Web Version, 8/27/2018 Photo: Ameca splendens. Source: Getty Images. Available: https://rmpbs.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/128605480-endangered-species/butterfly-goodeid- ameca-splendens/#.Wld1X7enGUk. (January 2018). 1 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Fuller (2018): “This species is confined to a very small area, the Río Ameca basin, on the Pacific Slope of western Mexico (Miller and Fitzsimons 1971).” From Goodeid Working Group (2018): “This species comes from the Pacific Slope and inhabits the Río Ameca and its tributary, the Río Teuchitlán in Jalisco. More habitats in the ichthyological [sic] closely connected Sayula valley have been detected quite recently.” Status in the United States From Fuller (2018): “Reported from Nevada. Records are more than 25 years old and the current status is not known to us. One individual was taken in November 1981 (museum specimen) and another in August 1983 from Rodgers Spring, Nevada (Courtenay and Deacon 1983, Deacon and Williams 1984). Others were seen and not collected (Courtenay, personal communication).” From Goodeid Working Group (2018): “Miller reported, that on 6 May 1982, this species was collected in Roger's Spring, Clark County, Nevada, (pers. comm. to Miller by P.J. Unmack) where it is now extirpated. It had been exposed there with several other exotic species (Deacon [and Williams] 1984).” From FAO (2018): “Status of the introduced species in the wild: Probably not established.” From Froese and Pauly (2018): “Raised commercially in Florida, U.S.A.” Means of Introductions in the United States From Fuller (2018): “Probably an aquarium release.” Remarks From Fuller (2018): “Synonyms and Other Names: butterfly goodeid.” 2 From Goodeid Working Group (2018): “Some hybridisation attempts have been undertaken with the Butterfly Splitfin to solve its relationship. -

Anarchist Movements in Tampico & the Huaste

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Peripheries of Power, Centers of Resistance: Anarchist Movements in Tampico & the Huasteca Region, 1910-1945 A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Latin American Studies (History) by Kevan Antonio Aguilar Committee in Charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Co-Chair Professor Michael Monteon, Co-Chair Professor Max Parra Professor Eric Van Young 2014 The Thesis of Kevan Antonio Aguilar is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii DEDICATION: For my grandfather, Teodoro Aguilar, who taught me to love history and to remember where I came from. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………..…………..…iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………...…iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………….v List of Figures………………………………………………………………………….…vi Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………vii Abstract of the Thesis…………………………………………………………………….xi Introduction……………………………………………………………………………......1 Chapter 1: Geography & Peripheral Anarchism in the Huasteca Region, 1860-1917…………………………………………………………….10 Chapter 2: Anarchist Responses to Post-Revolutionary State Formations, 1918-1930…………………………………………………………….60 Chapter 3: Crisis & the Networks of Revolution: Regional Shifts towards International Solidarity Movements, 1931-1945………………95 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….......126 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………129 v LIST -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Temporal Diversification of Mesoamerican Cichlid Fishes Across

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 31 (2004) 754–764 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Temporal diversification of Mesoamerican cichlid fishes across a major biogeographic boundary C. Darrin Hulsey,a,* Francisco J. Garcıa de Leon, b Yara Sanchez Johnson,b Dean A. Hendrickson,c and Thomas J. Neara,1 a Center for Population Biology, Department of Evolution and Ecology, University of California-Davis, Davis, CA 95616, USA b Laboratorio de Biologıa Integrativa, Instituto Tecnologico de Cuidad Victoria (ITCV), Mexico c Section of Integrative Biology, University of Texas-Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA Received 18 June 2003; revised 26 August 2003 Abstract The Mexican Neovolcanic Plateau sharply divides the vertebrate fauna of Mesoamerica where the climate of both the neotropics and temperate North America gradually blend. Only a few vertebrate groups such as the Heroine cichlids, distributed from South America to the Rio Grande in North America, are found both north and south of the Neovolcanic Plateau. To better understand the geography and temporal diversification of cichlids at this geologic boundary, we used mitochondrial DNA sequences of the cy- tochrome b (cyt b) gene to reconstruct the relationships of 52 of the approximately 80 species of Heroine cichlids in Mesoamerica. Our analysis suggests several cichlids in South America should be considered as part of the Mesoamerican Heroine clade because they and the cichlids north of the Isthmus of Panama are clearly supported as monophyletic with respect to all other Neotropical cichlids. We also recovered a group containing species in Paratheraps + Paraneetroplus + Vieja as the sister clade to Herichthys. Herichthys is the only cichlid clade north of the Mexican Plateau and it is monophyletic. -

TAKE TOWN on PANUCO RIVER REVENUE BILL by Senate Leaders

RIO GRANDE DELTA EXPOSITION-BROWNSVILLE-FEBRUARY 25,26, 27,28, 29, MARCH 1 j Pmpiat Machinery ! PIPE FITTINGS ... _ .. ; Many «aHoada In atock to fill F»irl»nki Mon* 1 % to It h. p. o,„ ««* I. tb. b..t Oil j | and Atlaa Engiow ^|] ,iHI| «|ia|*« and kind*. Wa Pa no pa. a. fai atock. Cantrifncal B are headquarter W. H. Potegaat Ca x j , u _ ““L'ZL?*" -—- Today s News in Today’s Paper Fall leased wire Associated Press news service -—- — ■■■ ii ■■■■■■■■ ■ .—.i ■■ji.j ,, —.... .--i VOL. XXX, Xo. 233 BROWNSVILLE, TEXAS, FRIDAY FEBRUARY 22,1924 SIX PAGES TODAY ESTABLISHED 1893 .'J AFTERNOON, "" * 1 1 * ■■ — — ■ — ■ —' -- —1 1 — ■■ — ---r— -■■■■■ mj-u-un-n.^ ‘‘ruwu^r r-n-‘-^ ->f-ij-i_t-xj-u-<j~,/-u-i -u-J-.-n-n-^- -'------------------ --------- --- I -- --- Commander States REBEL FORCES Legion WASHINGTON Abandonment Mellon Juggled Figures Where he wearied eye Whom envy dared not hate. paugherty may repose TAKE TOWN ON When gazing on the great. Bequeathed the name of Senate Leaders Cause to Defeat Soldier Bonus When* neither guilty glory glows Washington by --—-—---—-— Nor despicable state? To make men blush there wa» the republican party." John II. i.hiintt, Yes. fine the first, the last, the best. but one. States That Big Business is The t'incinnntus of the Lord PANUCO RIVER national commander «»f the Anieri<nn West, Byron of Tense Situation / its l.cgion. declared b*>re today in nn ud- Spending War Profits This morning, as wr listened to the cannon in Port Brown (looming its Today dti* s i « Aiiieri-au Legion represent!! customary salute in honor of the country's greatest hero, we thought.