Forgiveness and Healing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ST. PIUS X CATHOLIC COMMUNITY 16 Smithville Crescent, St

ST. PIUS X CATHOLIC COMMUNITY 16 Smithville Crescent, St. John’s, NL A1B 2V2 Tel.# 754-0170 Finding God in All Things 29th SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME October 18, 2020 IGNATIAN INSPIRATIONS Our cover this weekend features a short introduction to Ignatian Spirituality. We invite you to try this over the next few Sundays. To Begin For those who love, nothing is too difficult, especially when it is done for the love of our Lord Jesus Christ. Scripture “I give you a new commandment: love one another. As I have loved you, so you also should love one another”. (John 13:34) Prayer Lord God, as I look at the day ahead and wonder how I will get everything done, I think about why I am here in the first place: because you love me. How simple, and yet, how magnificent! You have created me to love, praise, and serve you, so that I might live forever with you. Help me see everything I do today as an expression of my love for you. Action I will write the word “love” next to each item on my to-do list as a reminder that when I do things for love of God and neighbor, nothing is too difficult. SOURCE: 30 Days with Saint Ignatius of Loyola, Page 3 Fr. Earl Smith, SJ (Pastor and Superior of St. John’s Jesuits) ([email protected]) Fr. Wayne Bolton, SJ (Associate Pastor) ([email protected] ) Maria R. Kelsey (Pastoral Assistant and Religious Education Coordinator) ([email protected]) Parish E-mail: [email protected] Webpage: www.spx.ca Archdiocesan Webpage: www.rcsj.org www.spx.ca SCRIPTURE READINGS CATHOLIC WOMEN’S LEAGUE FOR NEXT SUNDAY NOTES October 25, 2020 You could read/discuss/pray with your family, The month of October is dedicated to with friends or by yourself.’ the Most Holy Rosary First Reading: Exodus 22:20-26 During this month, members of the Second Reading: 1st Thessalonians 1:5-10 CWL invite you to join the praying of Psalm: 18 the Rosary after the 9:30 am Mass (approximately Gospel: Matthew 22:34-40 10:00 am) on Tuesday and Thursday mornings. -

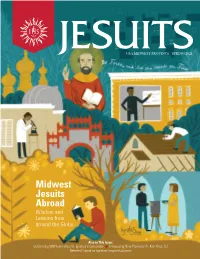

Midwest Jesuits Abroad Wisdom and Lessons from Around the Globe

USA MIDWEST PROVINCE | SPRING 2021 Midwest Jesuits Abroad Wisdom and Lessons from around the Globe Also in This Issue: Celebrating 500 Years since St. Ignatius’s Conversion n Introducing New Provincial Fr. Karl Kiser, SJ Retirees Embark on Ignatian-inspired Journey Dear Friends, I am humbled. These are the words I used when I wrote my first message in this magazine as the first provincial of the newly formed USA Midwest Province. And they are just as true today—in this, my last message to you as provincial in Jesuits Magazine. I have been humbled to work with my Jesuit brothers and our lay collaborators to pursue our mission, and I have been humbled to experience the fruits of your prayers and support in all that we do. I am pleased that Father General Arturo Sosa, SJ, has named Fr. Karl Kiser, SJ, as our next provincial (see page 12). A proven leader, Fr. Kiser brings considerable pastoral and administrative gifts, along with international experience, to his role of caring for the Jesuits and the ministries of our province. I am equally grateful for his deep and abiding love for the Society of Jesus and its service to the Church. One such mutual goal involves the Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation dialogue that has been taking place among the Society of Jesus, Georgetown University, and the Descendants of Jesuit Slaveholding (page 9). President of the Jesuit Conference, former Chicago-Detroit Provincial Timothy Kesicki, SJ, has been engaged in this vital work for several years; it is just now bearing fruit. -

Meet the New Superior General of the Society of Jesus

JESUIT newsletter of the jesuits in english canada WINTER 2017 IN THIS ISSUE Meet the new Letter from the National Director 2 of the Jesuit Superior General Development Office of the Society 3 Men in Formation of Jesus Scotch Nosing 5 and Dinner 10 Jesuit Immersion 12 In Memoriam 15 Enrollment Cards FEATURES 7 CANADIAN CANOE PILGRIMAGE he Society of Jesus welcomed a new Superior General, Father Arturo Sosa, SJ in October 2016. The election of Fr. Sosa in Rome during General TCongregation 36, makes him the 31st General of the Society. Fr. Sosa was born in Caracas, Venezuela in 1948 and, until his election, he was Delegate for Interprovincial Houses for the Society in Rome, as well as serving on the General Council as a Counsellor. 9 FEATURE: FR. NORM DODGE, SJ He obtained a licentiate in philosophy in 1972 and a doctorate in political science in 1990. He speaks Spanish, Italian, English, and some French. Between 1996 and 2004, Fr. Sosa was provincial superior of the Jesuits in Venezuela. Before this, he served as province co-ordinator for the social apostolate and was also director of the Gumilla Social Centre, a centre for research and social action in Venezuela. Much of his life has been dedicated to research and teaching. He held different 11 positions in academia including serving as rector of the Catholic University of INTERNATIONAL FEATURE Táchira, Venezuela. Jesuits in English Canada ◆ 43 Queen's Park Cres., E., Toronto, ON M5S 2C3 ◆ www.jesuits.ca JESUIT JESUIT LETTER FROM THE newsletter NATIONAL DIRECTOR OF THE of the jesuits in JESUIT DEVELOPMENT OFFICE english canada Jesuit Development Office Dear Friends, National Director: Fr. -

Taizé Integrate Their Inner and Outer Life with God and with All Creation

Ignatius Jesuit Centre is a place of peace that welcomes a global community of people who seek to Taizé integrate their inner and outer life with God and with all Creation. Advent & Lenten We promote right relationships with Weekend Retreats with God, with each other and with the Chants of Taizé Creation, especially through spiritual Facilitated by Erik Oland, SJ, development in the tradition of the Tarcia Gerwing & Dan Leckman, SJ Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola and through deep 2016-2017 engagement with this land. Loyola House Retreat & Training Centre is central to the Ignatius Jesuit Centre, located one km north of Guelph on over 600 acres of beautiful farmland, with walking trails through rolling hills, woods and wetlands—all of it an integral part in our retreats and programs. Loyola House Retreat & Training Centre 5420 Highway 6, North Guelph ON N1H 6J2 Registrar: 519.824.1250 ext 266 IgnatiusIgnatius JJesuitesuit CCentreentre A Pl ace of Peace Fax: 519.767.0994 [email protected] Loyola House loyolahouse.com Retreat & Training Centre Printed on 100% recycled paper ignaƟusguelph.ca | loyolahouse.com Retreats and Programs Erik Oland, SJ has been associated with the is a town in France, where some It is our intention to ensure the financial Taizé Ignaus Jesuit Centre since 1998. His sustainability of the retreats and 90 brothers from professional background is in Classical music programs we provide at the Ignatius various and Spirituality. Fr. Oland, SJ had the opportuni- Jesuit Centre. Cancellations represent an Chrisan ty to be hosted by the monks of Taizé, France in expense to the Centre and a lost 2007. -

2020 Jésuites Canadiens Numéro 1

2020 1 jesuites.ca Être avec pour agir ensemble : Les stagaires de Mer et Monde page 5 Ressourcement et croissance personnelle à Manresa page 8 Répondre à l’urgence climatique page 17 La spiritualité au bout des doigts: 5 applications à utiliser page 20 Mot du directeur Photo : Dominik Haake une campagne électorale qui a duré près de deux mois au Canada, nous continuons de faire Après face à des tensions à propos de la migration, de l'intolérance des minorités, des systèmes économiques cupides ou encore de la négligence à l'endroit du vivant. Et depuis des décennies, notre Église vit des cas dramatiques et douloureux d'abus dans ses rangs, abus qui érodent le message de Jésus. Mais s'il est certain que nous ne pouvons pas ignorer ce qui se passe autour de nous, il ne faut pas non plus que nous restions paralysés. Nous continuons donc d'examiner et de détecter les sources de courage et de consolation, au-delà des dissonances rencontrées, et de suivre l'appel à nous renouveler. En regardant ce magazine, je vois ainsi les fruits d'hommes et de femmes, religieux et laïcs, jeunes et vieux, tous unis dans une mission de réconciliation. Ils sont le fruit d'une province jésuite qui couvre 9,98 millions de kilomètres carrés, de nombreuses langues et cultures - francophone, anglophone, autochtones - et qui est aussi nourrie par ceux et celles qui sont venus et continuent d’arriver de dizaines de pays du monde entier. Cet esprit de renouveau et cette énergie vers notre mission commune se font sentir à travers les pages. -

Jesuit Education

JESUIT EDUCATION THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY may 14, 2012 $3.50 OF MANY THINGS PUBLISHED BY JESUITS OF THE UNITED STATES s a former university presi - vide a compass that will facilitate the dent, I am always happy when kind of intellectual, ethical, social and PRESIDENT AND PUBLISHER A America turns its attention to religious integration Jesuit education JOHN P. S CHLEGEL , S.J. Jesuit higher education. For over three has traditionally espoused. decades I called campus home at five Undoubtedly members of Jesuit uni - EDITOR IN CHIEF Jesuit institutions. But it wasn’t until versities fall short of perfection in exe - Drew Christiansen, S.J. recently, when I asked, “When is spring cuting this vision, but that does not EDITORIAL DEPARTMENT break?” that I realized how much I mean we do not continue to seek the MANAGING EDITOR missed the groves of academe. greater good. Students may champion Robert C. Collins, S.J. Jesuit universities in the United the secular but not lose the faith; indeed, EDITORIAL DIRECTOR States cast a wide shadow of academic they may develop a rich spirituality and Karen Sue Smith excellence and community engagement. sense of justice; they may adopt a cause ONLINE EDITOR But that was not always so. It was only or develop political views different from Maurice Timothy Reidy in the years following World War II their parents; or they may be civilly dis - LITERARY EDITOR that many of these schools evolved into engaged. Yes, they may return home and Raymond A. Schroth, S.J. authentic universities, many of them even live in their former rooms, but their POETRY EDITOR moving into the ranks of America’s Jesuit education remains within them— James S. -

Annual Reports

Annual Reports The Catholic Women’s League of Canada Hamilton Diocesan Council 2019 Hamilton Diocesan Council of The Catholic Women’s League of Canada Care for Our Common Home Table of Contents MESSAGES Most Reverend Douglas Crosby, Bishop of Hamilton……….. 4 Reverend John Redmond, Diocesan Spiritual Advisor………. 5 Colleen Perry, Provincial President President……………………. 6 Catherine Feren, Diocesan President…………………………………. 7 BOOK OF LIFE……………………………………………………………………………… 12 DIOCESAN OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE REPORTS Diocesan Council Executive………………………………………………… 20 Past President/Historian……………………………………………………… 22 Secretary…………………………………………………………………………….. 24 Treasurer…………………………………………………………………………….. 26 DIOCESAN COMMITTEE REPORTS Spiritual Development ……………………………………………………….. 31 Organization………………………………………………………………………… 33 Christian Family Life……………………………………………………………. 38 Community Life……………………………………………………………………. 41 Education and Health…………………………………………………………… 44 Communications…………………………………………………………………… 46 Resolutions…………………………………………………………………………… 49 Legislation……………………………………………………………………………. 51 Life Member Liaison……………………………………………………………… 54 REGIONAL REPORTS Brant………………………………………………………………………………………………… 59 Hamilton…………………………………………………………………………………………… 63 Kitchener…………………………………………………………………………………………… 88 North…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 110 SPECIAL MENTIONS Frances Lovering Woman of the Year Award……………………… 116 Diocesan 100th Anniversary………………………………………………… 118 Hamilton Diocesan Council of The Catholic Women’s League of Canada Care for Our Common Home Mission -

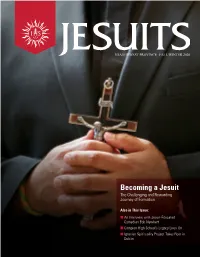

Becoming a Jesuit the Challenging and Rewarding Journey of Formation

USA MIDWEST PROVINCE | FALL/WINTER 2020 Becoming a Jesuit The Challenging and Rewarding Journey of Formation Also in This Issue: n An Interview with Jesuit-Educated Comedian Bob Newhart n Campion High School’s Legacy Lives On n Ignatian Spirituality Project Takes Root in Dublin Dear Friends, As we near the end of 2020, I find myself reflecting on the ways that the world has changed over these last 12 months. The onset of the pandemic, followed by economic collapse, and the social and political upheaval of an election year—any of these would be remarkable on their own. Yet in all of this, we have adapted to find new ways of worshipping, socializing, working, sharing, and learning together. Yes, these adjustments were and continue to be stressful, but these are also times of grace, as we see faith and courage overcome desolation and fear. Perhaps that is why it’s no surprise that our schools across the Midwest rose swiftly to meet the challenges of COVID-19 (page 14), stepping up in the same way Jesuits have done since our founding. In Cincinnati, at Bellarmine Parish and Xavier University (page 20), the pandemic united the parish and university to work together in unique and innovative ways, as perhaps nothing else could have. At the same time, the Seminars in Ignatian Formation and Leadership (SIF) program (page 19) continued to offer training in the Spiritual Exercises to those serving at our Jesuit works. This vital program transitioned successfully to an online model, so that the ripple effect of this training continues. -

Cameron Bellm

Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places: Through the Year with Ignatian Spirituality Edited by Cameron Bellm Art by Erica Ploucha, Erica Tighe Campbell and Molly Noem Fulton In Celebration of the Ignatian Year 2021-2022 Jesuits.org ©2021 Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States Contents Introduction, by Cameron Bellm 4 Summer A Prayer for the Feast of St. Ignatius, by Cameron Bellm 8 A Pilgrim’s Summer Vacation, by Josh Utter 9 Creation Again, by Fr. Greg Kennedy, SJ 10 The Examen, by Cameron Bellm 11 Finding God in All Things, by Grace Salceanu 13 The Spiritual Exercises, by Nick Ripatrazone 16 Autumn Divine Presence in the Season of Creation, by Ashley Hai? Vân Trân` 20 St. Alphonsus Rodriguez and the Call to Hospitality, by Br. Matt Wooters, SJ 22 A Prayer for Black Catholic History Month, by Cameron Bellm 24 A Prayer for All Saints’ Day, by Joan Rosenhauer 26 All Souls’ Day, by Mike Jordan Laskey 28 The Challenge of Blessed Miguel Pro, by Christopher Smith, SJ 30 Autumn Speaks, by Vinita Hampton Wright 33 Winter Advent, by MegAnne Liebsch 38 In the Nativity, by Elise Gower 40 Imaginative Prayer: Where We Meet, by Danielle Harrison 41 A New Serenity Prayer, by Fr. James Martin, SJ 43 St. Francis Xavier, by Fr. Michael Rossmann, SJ 45 Christmas, by Shannon K. Evans 47 Mappers of Time and Space, by Br. Guy Consolmagno, SJ 48 Spring Ash Wednesday, by Fr. Mark Thibodeaux, SJ 52 Lent: Resurrection Journey, by Sr. Colleen Gibson, SSJ 54 The Novena of Grace, by Fr. -

Ignaɵan Training Program in Spiritual Direcɵon (Offered in Three Phases) - Program Outline

Directors: Our team of experienced spiritual Endorsement directors includes Jesuits, lay persons, religious, “I could not have asked for greater hospitality, and priests. IgnaƟan inclusion as a team member, formaƟon and Pre-requisites: support. This has been a deeply transforming Successful parcipaon in at least one experience that will bear much fruit in my individually directed 8-day retreat Training personal life and ministry.” —Fr. Bill Brennan Fluency in wrien and spoken English Compleon of each phase or appropriate Program equivalent prior to acceptance into the next Ignatius Jesuit Centre is a place of peace that phase. in Spiritual welcomes a global community of people who ApplicaƟon Process: seek to integrate their inner and outer life with Obtain an applicaon package from the God and with all Creation. Registrar. See contact informaƟon below. DirecƟon Complete and return the enre applicaon We promote right relationships with God, with and a non-refundable applicaon fee of $100 2018-2019 CDN by August 1. Note: If you reside outside each other and with Creation, especially Canada or the USA, we advise you to apply by Offered in three phases through spiritual development in the tradition May 1 and immediately begin process to of the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of obtain a visa. Loyola and through deep engagement with this land. Loyola House Retreat & Training Centre is central to the Ignatius Jesuit Centre, located one km north of Guelph on over 600 acres of beautiful farmland, with walking trails through rolling hills, woods and wetlands—all of it an integral part in our retreats and programs. -

Jesuit Newsletter – Summer 2020

newsletter of the office of advancement SUMMER 2020 IN THIS ISSUE Letter from the 2 Director Faith in the Time 3 of COVID-19 Ordinations 4 2020 11 In Memoriam 14 Scholarships 15 Enrollment Cards Jesuits care for their FEATURES elderly brothers during COVID-19 outbreak A personal reflection by Jesuit scholastics Oliver Capko and Adam Pittman and Father Gilles Mongeau 8 DONOR PROFILE OVID-19 made its way to nearly every corner of the world, shutting down economies, creating rules about “physical distancing,” and even altering how Cwe attend religious services. While the pandemic grew in Canada, many Jesuits felt relatively untouched until we received word that our most vulnerable brothers had contracted the disease. On April 22, Father Erik Oland, Provincial of the Canadian 9 Jesuit Province, received notice that an outbreak of COVID-19 had been declared at our JESUIT PROFILE Province infirmary in Pickering, ON. Even before a request could go out to the Province, scholastics had already volunteered to go and help. By April 27, five Jesuits had arrived at the infirmary to provide personal care and custodial support – a much welcomed addition to a dwindling staff. 10 READ MORE P3 ▶ APOSTOLATE PROFILE Jésuites du Canada / Jesuits of Canada ◆ 43 Queen's Park Cres. E., Toronto, ON M5S 2C3 ◆ www.jesuits.ca JESUIT JESUIT newsletter of the LETTER FROM THE office of advancement DIRECTOR Director: Barry J. Leidl Contributors: Oliver Capko, SJ, Fr. Gilles Mongeau, SJ, Adam Pittman, SJ, Fr. Michael J. Rogers, SJ, Dear Friends in the Lord, Regis College, Salt + Light TV, José Sanchez, Erica Zlomislic The last few months were a time when it was easy to become hopeless and to despair. -

Jesuits 2020

Cover: Photo: María Teresa Urueña, Servicio Jesuita Panamazónico A Ticuna indigenous man looks to the future. Lake Tarapoto, Puerto Nariño, Amazonia An opportunity to keep in mind the Synod on the Pan-Amazon Region held in October 2019. The theme of this encounter, “New Ways for the Church and for an Integral Ecology,” is directly related to the Universal Apostolic Preferences of the Society of Jesus, in particular the care for “our Common Home.” Published by the General Curia of the Society of Jesus Communications and Public Relations Department Borgo Santo Spirito 4 - 00193 Roma, Italia Tel: (+39) 06 698-68-289 E-Mail: [email protected] – [email protected] Websites: sjcuria.global – jesuits.global Twitter.com/TheJesuits Facebook.com/TheJesuits Our thanks to all those who contributed to this edition. Publisher: Pierre Bélanger, SJ Assistant: Caterina Talloru Coordination and graphic design: Grupo de Comunicación Loyola, Spain Printing: MCCGraphics, SS. Coop. – Loiu (Vizcaya, Spain) October 2019 2020 Jesuits THE SOCIETY OF JESUS IN THE WORLD Table of Contents Presentation A mission of reconciliation and justice based on faith Arturo Sosa, SJ .......................................................................................................................... 8 The pulsating life Pierre Bélanger, SJ ..................................................................................................................... 9 • UAPs to streamline formation in South Asia Raj Irudaya, SJ ......................................................................................................................