Root River Watershed Landscape Stewardship Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Chapter 85

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 85.011 CHAPTER 85 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION STATE PARKS, RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES 85.06 SCHOOLHOUSES IN CERTAIN STATE PARKS. 85.011 CONFIRMATION OF CREATION AND 85.20 VIOLATIONS OF RULES; LITTERING; PENALTIES. ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE PARKS, STATE 85.205 RECEPTACLES FOR RECYCLING. RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES. 85.21 STATE OPERATION OF PARK, MONUMENT, 85.0115 NOTICE OF ADDITIONS AND DELETIONS. RECREATION AREA AND WAYSIDE FACILITIES; 85.012 STATE PARKS. LICENSE NOT REQUIRED. 85.013 STATE RECREATION AREAS AND WAYSIDES. 85.22 STATE PARKS WORKING CAPITAL ACCOUNT. 85.014 PRIOR LAWS NOT ALTERED; REVISOR'S DUTIES. 85.23 COOPERATIVE LEASES OF AGRICULTURAL 85.0145 ACQUIRING LAND FOR FACILITIES. LANDS. 85.0146 CUYUNA COUNTRY STATE RECREATION AREA; 85.32 STATE WATER TRAILS. CITIZENS ADVISORY COUNCIL. 85.33 ST. CROIX WILD RIVER AREA; LIMITATIONS ON STATE TRAILS POWER BOATING. 85.015 STATE TRAILS. 85.34 FORT SNELLING LEASE. 85.0155 LAKE SUPERIOR WATER TRAIL. TRAIL PASSES 85.0156 MISSISSIPPI WHITEWATER TRAIL. 85.40 DEFINITIONS. 85.016 BICYCLE TRAIL PROGRAM. 85.41 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI PASSES. 85.017 TRAIL REGISTRY. 85.42 USER FEE; VALIDITY. 85.018 TRAIL USE; VEHICLES REGULATED, RESTRICTED. 85.43 DISPOSITION OF RECEIPTS; PURPOSE. ADMINISTRATION 85.44 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI TRAIL GRANT-IN-AID 85.019 LOCAL RECREATION GRANTS. PROGRAM. 85.021 ACQUIRING LAND; MINNESOTA VALLEY TRAIL. 85.45 PENALTIES. 85.04 ENFORCEMENT DIVISION EMPLOYEES. 85.46 HORSE -

ROOT RIVER ONE WATERSHED, ONE PLAN -I- SWCD Soil and Water Conservation District

Cold Snap Photography Prepared For: Root River Planning Partnership Prepared By: Houston Engineering, Inc. Photo by Bob Joachim Root River Watershed | ONE WATERSHED, ONE PLAN List of PLan Abbreviations i Plan Definitions iii Executive Summary iv 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1 Preamble 1-1 1.2 Plan Area 1-1 1.3 Watershed Characteristics 1-4 1.4 Plan Overview 1-4 1.5 Plan Partners and Roles in Plan Development 1-5 1.6 Incorporating Comments into the Plan __________________1-7 2. ANALYSIS AND PRIORITIZATION OF RESOURCES, CONCERNS, AND ISSUES CAUSING CONCERN 2-1 2.1 Definitions 2-1 2.2 Identifying Potential Resource Concerns and Issues 2-2 2.3 Prioritizing Potential Resource Concerns and Issues 2-13 2.4 Priority Resource Concerns and Issues 2-14 2.4.1 "A" Level Priorities 2-14 2.4.1.1 Description and Resource Concern Locations 2-14 2.4.1.2 Issues Affecting "A" Level Priority Resource Concerns 2-18 2.4.2 "B" Level Priorities 2-18 2.4.2.1 Description and Landscape Locations 2-18 2.4.2.2 Issues Affecting “B” Level Priority Resource Concerns 2-26 2.4.3 "C" Level Priorities 2-26 2.4.3.1 Issues Affecting “C” Level Priority Resource Concerns 2-35 2.5 Use of Priority Categories in Plan Implementation 2-35 2.6 Emerging Issues 2-35 2.6.1 "Scientific and Technical Emerging Issues 2-36 2.61.1 Climate Change and Infrastructure Resilience 2-36 2.6.1.2 Endocrine Active Compounds 2-37 2.6.1.3 Water Movement Within a Karst Landscape 2-37 2.6.1.4 Improving Soil Health 2-37 2.6.1.5 Buffers for Public Waters and Drainage Systems 2-38 2.6.1.6 Invasive Species 2-38 2.6.1.7 -

Delineation Percentage

Lake Superior - North Rainy River - Headwaters Lake Superior - South Vermilion River Nemadji River Cloquet River Pine River Rainy River - Rainy Lake Little Fork River Mississippi River - Headwaters Leech Lake River Upper St. Croix River Root River Big Fork River Mississippi River - Winona Upper/Lower Red Lake Kettle River Mississippi River - Lake Pepin Mississippi River - Grand Rapids Mississippi River - La Crescent Crow Wing River Otter Tail River Mississippi River - Reno Mississippi River - Brainerd Zumbro River Redeye River Upper Big Sioux River Mississippi River - Twin Cities Snake River Des Moines River - Headwaters St. Louis River Rum River Lower Big Sioux River Lower St. Croix River Cottonwood River Minnesota River - Headwaters Cannon River Mississippi River - St. Cloud Long Prairie River Lake of the Woods Lower Rainy North Fork Crow River Mississippi River - Sartell Lac Qui Parle River Buffalo River Wild Rice River Minnesota River - Mankato Sauk River Rock River Redwood River Snake River Chippewa River Watonwan River Clearwater River East Fork Des Moines River Red River of the North - Sandhill River Upper Red River of the North Blue Earth River Red River of the North - Marsh River Roseau River Minnesota River - Yellow Medicine River Le Sueur River Little Sioux River Bois de Sioux River Cedar River Lower Minnesota River Pomme de Terre River Red Lake River Lower Des Moines River Upper Iowa River Red River of the North - Tamarac River Shell Rock River Two Rivers Rapid River Red River of the North - Grand Marais Creek Mustinka River South Fork Crow River Thief River Winnebago River Upper Wapsipinicon River 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% %Altered %Natural %Impounded %No Definable Channel wq-bsm1-06. -

Driftless Area National Wildlife Refuge

DRIFTLESS AREA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE McGregor, Iowa ANNUAL NARRATIVE REPORT FY2006 DRIFTLESS AREA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE McGregor, Iowa Fiscal Year 2006 _________________________ Prepared by Date _________________________ ______________________________ Refuge Manager Date Complex Manager Date ______________________________ Regional Chief, NWRS Date INTRODUCTION 1. Location The Driftless Area National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1989 for the protection and recovery of the threatened Northern monkshood and endangered Iowa Pleistocene snail. These species occur on a rare habitat type termed algific talus slopes. These are slopes with outflows of cold underground air that provide a glacial relict habitat to which certain species have adapted (see diagram below). The Driftless Area National Wildlife Refuge consists of ten units scattered throughout Allamakee, Clayton, Dubuque, and Jackson Counties in northeast Iowa. Total Refuge acreage is 811 acres with individual units ranging from 6 to 208 acres. Acquisition targets not only the algific slope, but surrounding buffer habitat that includes sinkholes important to air flow to the slope. Acquisition is ongoing, but limited due to insufficient funds. 2. Topography Refuge units are primarily forested and generally consist of steep topography with narrow creek valleys, large rock outcroppings, and karst features. Riparian and grassland habitat also occur on the Refuge. 3. Points of Interest The algific talus slope habitat of the Refuge harbors many unusual and rare plant and land snail species, some of which are also on the state threatened and endangered species list. These areas tend to be scenic with cliffs and rock outcroppings, springs, and coldwater streams. 4. Physical Facilities The Refuge office is located at the McGregor District of the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge, McGregor, Iowa. -

The Campground Host Volunteer Program

CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM THE CAMPGROUND HOST VOLUNTEER PROGRAM MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 1 CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. Addresses are listed at the back of this brochure. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Recreation 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 651-259-5607 [email protected] Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. Volunteers will set an example by being model campers, practicing good housekeeping at all times in and around the host site, and by observing all rules. -

Minnesota State Parks.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Afton State Park 4 2. Banning State Park 6 3. Bear Head Lake State Park 8 4. Beaver Creek Valley State Park 10 5. Big Bog State Park 12 6. Big Stone Lake State Park 14 7. Blue Mounds State Park 16 8. Buffalo River State Park 18 9. Camden State Park 20 10. Carley State Park 22 11. Cascade River State Park 24 12. Charles A. Lindbergh State Park 26 13. Crow Wing State Park 28 14. Cuyuna Country State Park 30 15. Father Hennepin State Park 32 16. Flandrau State Park 34 17. Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park 36 18. Fort Ridgely State Park 38 19. Fort Snelling State Park 40 20. Franz Jevne State Park 42 21. Frontenac State Park 44 22. George H. Crosby Manitou State Park 46 23. Glacial Lakes State Park 48 24. Glendalough State Park 50 25. Gooseberry Falls State Park 52 26. Grand Portage State Park 54 27. Great River Bluffs State Park 56 28. Hayes Lake State Park 58 29. Hill Annex Mine State Park 60 30. Interstate State Park 62 31. Itasca State Park 64 32. Jay Cooke State Park 66 33. John A. Latsch State Park 68 34. Judge C.R. Magney State Park 70 1 35. Kilen Woods State Park 72 36. Lac qui Parle State Park 74 37. Lake Bemidji State Park 76 38. Lake Bronson State Park 78 39. Lake Carlos State Park 80 40. Lake Louise State Park 82 41. Lake Maria State Park 84 42. Lake Shetek State Park 86 43. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

2009-2010 Winter Programs & Special Events Catalog

28 The Great Minnesota Ski Pass Get one and go! All cross-country skiers age 16 or older must have a Minnesota Ski Pass to use ski trails in state parks or state forests or on state or Grant-in-Aid trails. • You must sign your ski pass and carry it with you when skiing. • Rates are $5 for a daily ski pass, $15 for a one-season pass, and $40 for a three-season pass. • Ski pass fees help support and maintain Minnesota’s extensive cross-country ski trail system. • Daily ski passes are sold in park offices where weekend and holiday staff are available. Self-registration for one-season and three-season passes is available daily at all Minnesota state parks except Carley, George H. Crosby-Manitou, Monson Lake, and Schoolcraft. • You can also get daily, one-season, and three-season ski passes using Minnesota’s electronic licensing system, available at 1,750 locations around the state. To find a location near you, check the ELS page at mndnr.gov or call the DNR Information Center at 651-296-6157 or 1-888-646-6367. Metro Area Ski Trails 29 If you purchase a Minnesota ski pass for a special event such as candlelight ski event at a Minnesota state park, you may be wondering where else you can use it. Many cross-country ski trails throughout the state are developed and maintained with state and Grant-in-Aid funding. Grant-in-Aid trails are maintained by local units of government and local ski clubs, with financial assistance from the Department of Natural Resources. -

Root River Watershed Monitoring and Assessment Report

z c Root River Watershed Monitoring and Assessment Report June 2012 Acknowledgements MPCA Watershed Report Development Team: Michael Koschak, Mike Walerak, Pam Anderson, Dan Helwig, Bruce Monson, Dave Christopherson, David Duffey, Andrew Streitz Contributors: Citizen Stream Monitoring Program Volunteers Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Minnesota Department of Health Minnesota Department of Agriculture Fillmore County Soil and Water Conservation District The MPCA is reducing printing and mailing costs by using the Internet to distribute reports and information to a wider audience. Visit our Website for more information. MPCA reports are printed on 100% post-consumer recycled content paper manufactured without chlorine or chlorine derivatives. Project dollars provided by the Clean Water Fund (from the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment). Minnesota Pollution Control Agency 520 Lafayette Road North | Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 | www.pca.state.mn.us | 651-296-6300 Toll free 800-657-3864 | TTY 651-282-5332 This report is available in alternative formats upon request, and online at www.pca.state.mn.us Document number: wq-ws3-070400086 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 I. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 II. The Watershed Monitoring Approach ................................................................................ 3 -

Campground Host Program

Campground Host Program MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF PARKS AND TRAILS Updated November 2010 Campground Host Program Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. You may email your completed application to [email protected] who will forward it to your first choice park. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Trails 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 Email: [email protected] 651-259-5607 Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. -

2020 Root River Soil and Water Conservation District Annual Report

2020 Root River Soil and Water Conservation District Annual Report Larry Ledebuhr Family 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..……….……….……………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 MISSION STATEMENT.….................................................................................................................3 ORGANIZATIONAL BOUNDARIES.…….………………………………………………………………………………………...4 COUNTY LAND DESCRIPTION……………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 ORGANIZATIONAL HISTORY.………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 SWCD & NRCS STAFF 2020.……………………………………......................................................................7 ROOT RIVER SOIL & WATER CONSERVATION DISTRICT SUPERVISORS.…….…………………………….…..8 SUPERVISORS NOMINATION DISTRICT ….……………………………………………………………………………….….9 DISTRICT ACCOMPLISHMENTS.………………………………………………………………………………………………..10 EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH……………………………………………………………………………………………………….24 MEETINGS…………………………………….…………………………………………………………………………………….……24 STAFF DEVELOPMENT…….……………………….……………………………………………………………………………….25 PARTNERSHIPS………….…….……………………………………………………………………………………………………….26 2 INTRODUCTION This annual report is to assist and present an overview of the accomplishments and activities of the Root River Soil and Water Conservation District in a manner consistent to the District’s policies and long-range goals. MISSION STATEMENT The Root River Soil and Water Conservation District’s mission is to provide assistance to cooperators in managing the natural resources on their land. In addition, the district will continue to educate people on local conservation -

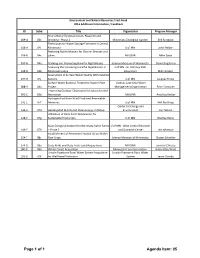

Of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd

Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund 2016 Additional Information / Feedback ID Subd. Title Organization Program Manager Prairie Butterfly Conservation, Research and 009‐A 03c Breeding ‐ Phase 2 Minnesota Zoological Garden Erik Runquist Techniques for Water Storage Estimates in Central 018‐A 04i Minnesota U of MN John Neiber Restoring Native Mussels for Cleaner Streams and 036‐B 04c Lakes MN DNR Mike Davis 037‐B 04a Tracking and Preventing Harmful Algal Blooms Science Museum of Minnesota Daniel Engstrom Assessing the Increasing Harmful Algal Blooms in U of MN ‐ St. Anthony Falls 038‐B 04b Minnesota Lakes Laboratory Miki Hondzo Assessment of Surface Water Quality With Satellite 047‐B 04j Sensors U of MN Jacques Finlay Surface Water Bacterial Treatment System Pilot Vadnais Lake Area Water 088‐B 04u Project Management Organization Brian Corcoran Improving Outdoor Classrooms for Education and 091‐C 05b Recreation MN DNR Amy Kay Kerber Hydrogen Fuel from Wind Produced Renewable 141‐E 07f Ammonia U of MN Will Northrop Center for Energy and 144‐E 07d Geotargeted Distributed Clean Energy Initiative Environment Carl Nelson Utilization of Dairy Farm Wastewater for 148‐E 07g Sustainable Production U of MN Bradley Heins Solar Energy Utilization for Minnesota Swine Farms U of MN ‐ West Central Research 149‐E 07h – Phase 2 and Outreach Center Lee Johnston Establishment of Permanent Habitat Strips Within 154‐F 08c Row Crops Science Museum of Minnesota Shawn Schottler 174‐G 09a State Parks and State Trails Land Acquisitions MN DNR Jennifer Christie 180‐G 09e Wilder Forest Acquisition Minnesota Food Association Hilary Otey Wold Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water System Acquisition Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water 181‐G 09f for Well Head Protection System Jason Overby Page 1 of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd.