HOW to IDENTIFY COMMON NEW YORK FROG and SALAMANDER EGGS Telling Frog Eggs Apart from Salamander Eggs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amphibian Identification Guide

Amphibian Migrations & Road Crossings Amphibian Identification Guide The NYSDEC Hudson River Estuary Program and Cornell University are working with communities to conserve forests, woodland pools, and the wildlife that depend on these critical habitats. This guide is designed to help volunteers of the Amphibian Migrations & Road Crossings Project identify species they observe during spring migrations, when many salamanders and frogs move from forest habitat to woodland pools for breeding. For more information about the project, visit http://www.dec.ny.gov/lands/51925.html. spotted salamander* (Ambystoma maculatum) Black to dark gray body with two rows of yellow spots. Widespread distribution in the Hudson Valley. Total length 5.0-8.0 in. Jefferson/blue-spotted salamander complex* (Ambystoma jeffersonianum x laterale) Brown to grayish black with blue-silver flecking. Less common. Note: Hybridization between Jefferson and blue-spotted salamander has created very variable appearances and individuals may have features of both species. Because even experts have difficulty distinguishing these two species in the field, we consider any sightings to be the ‘complex.’ Total length 3.0-7.5 in. marbled salamander* (Ambystoma opacum) Black or grayish-black body with white or gray crossbars along length of body. Stout body with wide head. Less common. (Breeds in the fall.) Total length 3.5-5.0 in. *Woodland pool breeding species. 0 inches 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Amphibian Migrations & Road Crossings: Amphibian Identification Guide Page 2 of 4 eastern newt (Notophthalmus viridescens) Terrestrial “red eft” stage of newt (above) is reddish-orange with two rows of reddish spots with black borders. -

Wood Frog (Rana Sylvatica): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project March 24, 2005 Erin Muths1, Suzanne Rittmann1, Jason Irwin2, Doug Keinath3, Rick Scherer4 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Fort Collins Science Center, 2150 Centre Ave. Bldg C, Fort Collins, CO 80526 2 Department of Biology, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA 17837 3 Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, P.O. Box 3381, Laramie, WY 82072 4 Colorado State University, GDPE, Fort Collins, CO 80524 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Muths, E., S. Rittman, J. Irwin, D. Keinath, and R. Scherer. (2005, March 24). Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/woodfrog.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the help of the many people who contributed time and answered questions during our review of the literature. AUTHORS’ BIOGRAPHIES Dr. Erin Muths is a Zoologist with the U.S. Geological Survey – Fort Collins Science Center. She has been studying amphibians in Colorado and the Rocky Mountain Region for the last 10 years. Her research focuses on demographics of boreal toads, wood frogs and chorus frogs and methods research. She is a principle investigator for the USDOI Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative and is an Associate Editor for the Northwestern Naturalist. Dr. Muths earned a B.S. in Wildlife Ecology from the University of Wisconsin, Madison (1986); a M.S. in Biology (Systematics and Ecology) from Kansas State University (1990) and a Ph.D. -

Sideration of the Population Sizes of Associated Pond Breeding Species

Adult Survivorship and Juvenile Recruitment in Populations of Crawfish Frogs (Lithobates Areolatus), with Additional Consideration of the Population Sizes of Associated Pond Breeding Species Item Type Thesis Authors Kinney, Vanessa C. Download date 01/10/2021 16:58:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/1808 ADULT SURVIVORSHIP AND JUVENILE RECRUITMENT IN POPULATIONS OF CRAWFISH FROGS (LITHOBATES AREOLATUS), WITH ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATION OF THE POPULATION SIZES OF ASSOCIATED POND BREEDING SPECIES _______________________ A thesis Presented to The College of Graduate and Professional Studies Department of Biology Indiana State University Terre Haute, Indiana ______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science _______________________ by Vanessa C. Kinney May 2011 Vanessa C. Kinney 2011 Keywords: amphibian breeding, Lithobates areolatus, drift fences - i - COMMITTEE MEMBERS Committee Chair: Michael J. Lannoo, Ph.D. Professor of Anatomy and Cell Biology Indiana University Committee Member: William A. Mitchell, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Biology Indiana State University Committee Member: John O. Whitaker, Jr., Ph.D. Professor of Biology Indiana State University Committee Member: John C. Maerz, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Vertebrate Ecology The University of Georgia - ii - ABSTRACT Crawfish Frog populations have declined significantly in both the northeastern and southwestern portions of their range, and are listed as state endangered in both Iowa and Indiana. They are animals with a secretive nature, and comparatively little is know about their basic life history and natural history. To address this gap, and to obtain the information necessary to manage for this species in areas of decline, I studied the breeding biology of two Crawfish Frog populations during 2009 and 2010. -

California Red-Legged Frog (Rana Aurora Draytonii) and Delta Smelt (Hypomesus Transpacificus)

Potential Risks of Atrazine Use to Federally Threatened California Red-legged Frog (Rana aurora draytonii) and Delta Smelt (Hypomesus transpacificus) Pesticide Effects Determinations Environmental Fate and Effects Division Office of Pesticide Programs Washington, D.C. 20460 February 19, 2009 Primary Authors: Mark Corbin, Senior Scientist Brian Anderson, Biologist Secondary Review: Paige Doelling, Ph.D., Acting Risk Assessment Process Leader James Hetrick, Ph.D., Senior Environmental Scientist Branch Chief, Environmental Risk Branch 3: Dana Spatz 2 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary..............................................................................................................7 1.1. Purpose of Assessment ..................................................................................................7 1.2. Assessed Chemicals.......................................................................................................7 1.3. Assessment Procedures..................................................................................................7 1.4. Atrazine Uses Assessed .................................................................................................9 1.5. Summary of Conclusions.............................................................................................10 2. Problem Formulation .........................................................................................................13 2.1 Purpose...........................................................................................................................13 -

Missouri's Toads and Frogs Booklet

TOADSMissouri’s andFROGS by Jeffrey T. Briggler and Tom R. Johnson, Herpetologists www.MissouriConservation.org © 1982, 2008 Missouri Conservation Commission Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Missouri Department of Conservation is available to all individuals without regard to their race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability. Questions should be directed to the Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 180, Jefferson City, MO 65102, (573) 751-4115 (voice) or 800-735-2966 (TTY), or to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Federal Assistance, 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Mail Stop: MBSP-4020, Arlington, VA 22203. Cover photo: Eastern gray treefrog by Tom R. Johnson issouri toads and frogs are colorful, harmless, vocal and valuable. Our forests, prairies, rivers, swamps and marshes are Mhome to a multitude of toads and frogs, but few people know how many varieties we have, how to tell them apart, or much about their natural history. Studying these animals and sharing their stories with fellow Missourians is one of the most pleasurable and rewarding aspects of our work. Toads and frogs are amphibians—a class Like most of vertebrate animals that also includes amphibians, salamanders and the tropical caecilians, which are long, slender, wormlike and legless. frogs and Missouri has 26 species and subspecies (or toads have geographic races) of toads and frogs. Toads and frogs differ from salamanders by having an aquatic relatively short bodies and lacking tails at adulthood. Being an amphibian means that tadpole stage they live two lives: an aquatic larval or tadpole and a semi- stage and a semi-aquatic or terrestrial adult stage. -

Toads and Frogs

Wildlife Center Classroom Series Amazing Amphibians: Toads and Frogs Wednesday September 13, 2017 Alex Wehrung, WCV: Ok, good afternoon everyone! It’s time for this month’s Wildlife Center Classroom Series, featuring some of my favorite animals: Alex Wehrung, WCV Alex Wehrung, WCV: I’m glad to see a lot of our regulars online today, but if we have any viewers out there joining us during a Classroom Series for the first time, let me know in the comments! Comment From BarbG cutest picture Alex Wehrung, WCV: Right?! That's the Fowler's Toad featured on our Current Patients page! Wildlife Center Classroom Series: Amazing Amphibians: Toads and Frogs Page 1 Comment From Lydia in VA ʕ•́ᴥ•̀ʔ Looking forward to class! I am in the process of learning more about native frogs and toads since we have moved and built a frog and toad palace. LOL Have been on VHS (Virginia Herp Society) page a lot lately Comment From Lydia in VA ʕ•́ᴥ•̀ʔ Hi Alex! This is a topic I am very interested in! Comment From Guest It's my first time! I'm excited Alex Wehrung, WCV: Welcome, Guest! We're glad to see you online! Comment From Lydia in VA ʕ•́ᴥ•̀ʔ Is this Guest one I was talking to on Sunday? About these classes? I hope so! Comment From Guest Thank you! Glad to be here :) Alex Wehrung, WCV: Today we’ll go over some of the basics of toad and frog anatomy, biology, and ecology to better understand this awesome critters and learn just how important they are. -

Frog Raising

COMMERCIAL POSSIBILITIES AND LIMITATIONS IN FROG RAISING While there may be some profit from selling frogs, artificial propa gation of frogs on a commercial basis has not been proved successful. The Fish and Wildlife Service has received thousands of inquiries about frog raising, but to the present time has heard of only two or three persons or institutions claiming any degree of success, so far as intensive frog culture is concerned. Much of the success claimed by a few II frog farms" appears to have been in the sale of breeding stock to would-be frog farmers. The Service has never engaged in frog culture and has never distributed or sold frogs, tadpoles, or frog eggs. Frog farming.--Most of the so-called frog farms, and those that should be least expensive and require the least labor, are simply natural marshy areas or ponds with food and environment suited to the needs of frogs. In such areas the frogs, left to themselves, will thrive and multiply; results may be improved by increasing the shoreline as mentioned below. A pond or swampy area may be stocked with adult frogs, or with eggs. In stocking with adults, better results may be obtained by introducing the frogs in late summer and fall in order that they may become accustomed to their ne~ surroundings before the egg-laying season--April iil the South and Mayor June farther north (in California some species begin breeding in January and February). Smaller species might be hatched to serve as food for the larger edible varieties, but the cannibalistic habit which this suggests dictates a segregation of the commercial species according to size to prevent their eat ing one another. -

Frogs and Toads Defined

by Christopher A. Urban Chief, Natural Diversity Section Frogs and toads defined Frogs and toads are in the class Two of Pennsylvania’s most common toad and “Amphibia.” Amphibians have frog species are the eastern American toad backbones like mammals, but unlike mammals they cannot internally (Bufo americanus americanus) and the pickerel regulate their body temperature and frog (Rana palustris). These two species exemplify are therefore called “cold-blooded” (ectothermic) animals. This means the physical, behavioral, that the animal has to move ecological and habitat to warm or cool places to change its body tempera- similarities and ture to the appropriate differences in the comfort level. Another major difference frogs and toads of between amphibians and Pennsylvania. other animals is that amphibians can breathe through the skin on photo-Andrew L. Shiels L. photo-Andrew www.fish.state.pa.us Pennsylvania Angler & Boater • March-April 2005 15 land and absorb oxygen through the weeks in some species to 60 days in (plant-eating) beginning, they have skin while underwater. Unlike reptiles, others. Frogs can become fully now developed into insectivores amphibians lack claws and nails on their developed in 60 days, but many (insect-eaters). Then they leave the toes and fingers, and they have moist, species like the green frog and bullfrog water in search of food such as small permeable and glandular skin. Their can “overwinter” as tadpoles in the insects, spiders and other inverte- skin lacks scales or feathers. bottom of ponds and take up to two brates. Frogs and toads belong to the years to transform fully into adult Where they go in search of this amphibian order Anura. -

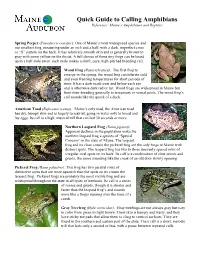

Quick Guide to Calling Amphibians Reference: Maine’S Amphibians and Reptiles

Quick Guide to Calling Amphibians Reference: Maine’s Amphibians and Reptiles Spring Peeper (Pseudacris crucifer): One of Maine’s most widespread species and our smallest frog, measuring under an inch and a half, with a dark, imperfect cross or “X” pattern on the back. It has relatively smooth skin and is generally brown to gray with some yellow on the throat. A full chorus of these tiny frogs can be heard up to a half-mile away; each male makes a shrill, pure, high-pitched breeding call. Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica): The first frog to emerge in the spring, the wood frog can tolerate cold and even freezing temperatures for short periods of ©USGS NEARMI time. It has a dark mask over and below each eye ©USGS NEARMI and is otherwise dark red or tan. Wood frogs are widespread in Maine but limit their breeding generally to temporary or vernal pools. The wood frog’s call sounds like the quack of a duck. ©James Hardy ©James Hardy American Toad (Bufo americanus): Maine’s only toad, the American toad has dry, bumpy skin and is largely terrestrial, going in water only to breed and lay eggs. Its call is a high, musical trill that can last 30 seconds or more. Northern Leopard Frog (Rana pipiens): Apparent declines in the population make the northern leopard frog a species of “Special Concern” in the state of Maine. The leopard frog and its close cousin the pickerel frog are the only frogs in Maine with distinct spots. The leopard frog has two to three unevenly spaced rows of irregular oval spots on its back. -

Commercial Frog Farming

PUBLICATION 420-255 Commercial Frog Farming Louis A. Helfrich, Extension Specialist, Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Scinces, Virginia Tech Richard J. Neves, Extension Specialist, Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Scinces, Virginia Tech James Parkhurst, Extension Specialist, Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Scinces, Virginia Tech Introduction Edible Frogs Raising and selling frogs on a commercial basis has A number of species of frogs, including the green frog not proven to be successful economically in Virginia (Rana clamitans), the leopard frog (Rana pipiens), or elsewhere in the United States to our knowledge. and the pickerel frog (Rana palustris), are harvested Although farming for frog legs sounds promising, from the wild and sold as a luxury food - frog legs - in operating a profitable frog farm seems to be more of a expensive restaurants. However, the bullfrog (Rana myth than a reality. Those few individuals who claim catesbeiana) has the greatest potential for culture. to be successful frog farmers generally are distribu- tors engaged in the selling of adult frogs, tadpoles, or The common bullfrog, often referred to as the “Giant frog eggs, frequently harvested from the wild. Frog” or “Jumbo Frog,” is the largest native North American species, often reaching 8 inches in body Many “frog farms” turn out to be natural marshy length. Because of its large size, the bullfrog is the areas, swamps or shallow ponds with abundant food most preferred and commonly attempted species for and habitat suitable to the needs of wild frogs. At farming. some frog farms, culture methods simply consist of increasing the shoreline area, erecting a fence to Breeding and the Life Cycle exclude predators and retain the frogs, and stocking Bullfrogs lay their eggs in shallow standing water wild frog eggs or tadpoles. -

Wisconsin Frog and Toad Survey 8 Early Late Summer Spring Spring Survey Survey Survey (70°F) (50°F) (60°F)

CALLING PHENOLOGY Male frogs and toads, like male songbirds, advertise their presence to females by singing or “calling”. Also like songbirds, each species has a distinctive call. Wisconsin frogs call during one or more of three general breeding periods: early spring (early season breeders), late spring (mid-season breeders), and summer (late season breeders). Wisconsin anurans typically call for 4 to 8 weeks; however, the wood frog is considered a short-term breeder and usually completes its breeding activity within two weeks. The onset and duration of frog calling is determined by local air and water temperatures and may vary considerably from year to year (the extended length of the survey periods accounts for these annual variations). Although air and water temperatures are considered more important than calendar dates for anuran breeding, WFTS surveys must be conducted within the three designated survey periods to be considered valid and to ensure consistency in statistical analyses. The anuran breeding phenology calendar (Figure 1) was determined for Portage County in central Wisconsin. Northern Wisconsin anurans may call a bit later and those in southern Wisconsin may call a bit earlier than the ranges presented in the calendar. Calling times are closely related to the types of water in which anurans breed. The early season breeders typically use temporary bodies of water for breeding: a slough adjacent to a lake, a pothole that dries up by mid-July, or a roadside ditch. The tadpoles of these species metamorphose rapidly in these warmer, shallower bodies of water. You may often hear spring peepers or other early season breeders calling from what appears to be the shore of a lake but it is likely that they are often in a nearby body of water where the water has warmed more quickly than the lake. -

Forest Hill FIELD GUIDE

Forest Hill FIELD GUIDE FOREST HILL ALMA COLLEGE GIRESD ii • Forest Hill History • Forest Hill Nature Area www.GratiotConservationDistrict.org Forest Hill Nature Area, located in northern Gratiot County, Michigan, is land that has been set aside for the preservation and appreciation of the natural world. The nature area has walking trails through 90 acres of gently rolling hills, open fields, wetlands, Let children walk with nature. Let them see the beautiful blendings willow thickets, and woodlots. Forest Hill Nature Area is home to a and communions of death and life. Their joys inseparable unity. As variety of wildlife such as white-tailed deer, muskrats, ducks and taught in woods and meadows. Plains and mountains. And turkeys. streams. -John Muir Also, over the years, some farm buildings were demolished while others were renovated. The Nature Area has evolved into an Forest Hill Nature Area: important outdoor educational resource for the school children in Gratiot and Isabella Counties as well as the citizens of Mid- In 1992, the Gratiot County Soil Conservation District acquired a Michigan. Since 1993, thousands of school children and adults 90 acre abandoned farm from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. have participated in field trips and nature programs at Forest Hill In 1993, the District leased the property to the Gratiot-Isabella Nature Area. RESD to develop an outdoor education center. The RESD named the property, the Forest Hill Nature Area and in partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began a major wetland restoration project. 3 Digital Nature Trail Forest Hill is brimming with biodiversity and all it entails: succession, evolution, adaptation, wildlife and food chains.