Logical Fallacies in Indonesian EFL Learners' Argumentative Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aristotle's Illicit Quantifier Shift: Is He Guilty Or Innocent

Aristos Volume 1 Issue 2 Article 2 9-2015 Aristotle's Illicit Quantifier Shift: Is He Guilty or Innocent Jack Green The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/aristos Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Green, J. (2015). "Aristotle's Illicit Quantifier Shift: Is He Guilty or Innocent," Aristos 1(2),, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.32613/aristos/ 2015.1.2.2 Retrieved from https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/aristos/vol1/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Aristos by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Green: Aristotle's Illicit Quantifier Shift: Is He Guilty or Innocent ARISTOTLE’S ILLICIT QUANTIFIER SHIFT: IS HE GUILTY OR INNOCENT? Jack Green 1. Introduction Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (from hereon NE) falters at its very beginning. That is the claim of logicians and philosophers who believe that in the first book of the NE Aristotle mistakenly moves from ‘every action and pursuit aims at some good’ to ‘there is some one good at which all actions and pursuits aim.’1 Yet not everyone is convinced of Aristotle’s seeming blunder.2 In lieu of that, this paper has two purposes. Firstly, it is an attempt to bring some clarity to that debate in the face of divergent opinions of the location of the fallacy; some proposing it lies at I.i.1094a1-3, others at I.ii.1094a18-22, making it difficult to wade through the literature. -

35 Fallacies

THIRTY-TWO COMMON FALLACIES EXPLAINED L. VAN WARREN Introduction If you watch TV, engage in debate, logic, or politics you have encountered the fallacies of: Bandwagon – "Everybody is doing it". Ad Hominum – "Attack the person instead of the argument". Celebrity – "The person is famous, it must be true". If you have studied how magicians ply their trade, you may be familiar with: Sleight - The use of dexterity or cunning, esp. to deceive. Feint - Make a deceptive or distracting movement. Misdirection - To direct wrongly. Deception - To cause to believe what is not true; mislead. Fallacious systems of reasoning pervade marketing, advertising and sales. "Get Rich Quick", phone card & real estate scams, pyramid schemes, chain letters, the list goes on. Because fallacy is common, you might want to recognize them. There is no world as vulnerable to fallacy as the religious world. Because there is no direct measure of whether a statement is factual, best practices of reasoning are replaced be replaced by "logical drift". Those who are political or religious should be aware of their vulnerability to, and exportation of, fallacy. The film, "Roshomon", by the Japanese director Akira Kurisawa, is an excellent study in fallacy. List of Fallacies BLACK-AND-WHITE Classifying a middle point between extremes as one of the extremes. Example: "You are either a conservative or a liberal" AD BACULUM Using force to gain acceptance of the argument. Example: "Convert or Perish" AD HOMINEM Attacking the person instead of their argument. Example: "John is inferior, he has blue eyes" AD IGNORANTIAM Arguing something is true because it hasn't been proven false. -

Scope Ambiguity in Syntax and Semantics

Scope Ambiguity in Syntax and Semantics Ling324 Reading: Meaning and Grammar, pg. 142-157 Is Scope Ambiguity Semantically Real? (1) Everyone loves someone. a. Wide scope reading of universal quantifier: ∀x[person(x) →∃y[person(y) ∧ love(x,y)]] b. Wide scope reading of existential quantifier: ∃y[person(y) ∧∀x[person(x) → love(x,y)]] 1 Could one semantic representation handle both the readings? • ∃y∀x reading entails ∀x∃y reading. ∀x∃y describes a more general situation where everyone has someone who s/he loves, and ∃y∀x describes a more specific situation where everyone loves the same person. • Then, couldn’t we say that Everyone loves someone is associated with the semantic representation that describes the more general reading, and the more specific reading obtains under an appropriate context? That is, couldn’t we say that Everyone loves someone is not semantically ambiguous, and its only semantic representation is the following? ∀x[person(x) →∃y[person(y) ∧ love(x,y)]] • After all, this semantic representation reflects the syntax: In syntax, everyone c-commands someone. In semantics, everyone scopes over someone. 2 Arguments for Real Scope Ambiguity • The semantic representation with the scope of quantifiers reflecting the order in which quantifiers occur in a sentence does not always represent the most general reading. (2) a. There was a name tag near every plate. b. A guard is standing in front of every gate. c. A student guide took every visitor to two museums. • Could we stipulate that when interpreting a sentence, no matter which order the quantifiers occur, always assign wide scope to every and narrow scope to some, two, etc.? 3 Arguments for Real Scope Ambiguity (cont.) • But in a negative sentence, ¬∀x∃y reading entails ¬∃y∀x reading. -

89% of Introduction-To-Psychology Textbooks That Define Or Explain

AMPXXX10.1177/2515245919858072Cassidy et al.Failing Grade 858072research-article2019 ASSOCIATION FOR General Article PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science Failing Grade: 89% of Introduction-to- 2019, Vol. 2(3) 233 –239 © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: Psychology Textbooks That Define sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919858072 10.1177/2515245919858072 or Explain Statistical Significance www.psychologicalscience.org/AMPPS Do So Incorrectly Scott A. Cassidy, Ralitza Dimova, Benjamin Giguère, Jeffrey R. Spence , and David J. Stanley Department of Psychology, University of Guelph Abstract Null-hypothesis significance testing (NHST) is commonly used in psychology; however, it is widely acknowledged that NHST is not well understood by either psychology professors or psychology students. In the current study, we investigated whether introduction-to-psychology textbooks accurately define and explain statistical significance. We examined 30 introductory-psychology textbooks, including the best-selling books from the United States and Canada, and found that 89% incorrectly defined or explained statistical significance. Incorrect definitions and explanations were most often consistent with the odds-against-chance fallacy. These results suggest that it is common for introduction- to-psychology students to be taught incorrect interpretations of statistical significance. We hope that our results will create awareness among authors of introductory-psychology books -

There Is No Fallacy of Arguing from Authority

There is no Fallacy ofArguing from Authority EDWIN COLEMAN University ofMelbourne Keywords: fallacy, argument, authority, speech act. Abstract: I argue that there is no fallacy of argument from authority. I first show the weakness of the case for there being such a fallacy: text-book presentations are confused, alleged examples are not genuinely exemplary, reasons given for its alleged fallaciousness are not convincing. Then I analyse arguing from authority as a complex speech act. R~iecting the popular but unjustified category of the "part-time fallacy", I show that bad arguments which appeal to authority are defective through breach of some felicity condition on argument as a speech act, not through employing a bad principle of inference. 1. Introduction/Summary There's never been a satisfactory theory of fallacy, as Hamblin pointed out in his book of 1970, in what is still the least unsatisfactory discussion. Things have not much improved in the last 25 years, despite fallacies getting more attention as interest in informal logic has grown. We still lack good answers to simple questions like what is a fallacy?, what fallacies are there? and how should we classifY fallacies? The idea that argument from authority (argumentum ad verecundiam) is a fallacy, is well-established in logical tradition. I argue that it is no such thing. The second main part of the paper is negative: I show the weakness of the case made in the literature for there being such a fallacy as argument from authority. First, text-book presentation of the fallacy is confused, second, the examples given are not genuinely exemplary and third, reasons given for its alleged fallaciousness are not convincing. -

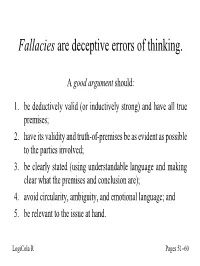

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

Critical Review All While Still Others Are Characterized Inadequately Or Incompletely

12 Some should not be classified as fallacies of relevance at critical review all while still others are characterized inadequately or incompletely. Copi maintains that in all fallacies of rele vance "their premisses are logically irrelevant to, and therefore incapable of establishing the truth of their conclusions" (pp. 9S-99). But this definition does not apply to the most important of the fallacies of relevance, the irrelevant conclusion (ignoratio elenchi). According to Copi, this fallacy is committed "when an argument sup Copi's Sixth Edition posedly intended to establish a particular conclusion is directed to proving a different conclusion" (p. 110). Copi even allows that the fallacy can be committed by one who may" succeed in proving his (irrelevant) conclusion" (my italics). The fault then is not that the premisses of such Ronald Roblin arguments are logically irrelevant to the conclusion drawn State University College at Buffalo from them, but that the conclusion drawn is insufficient to justify the conclusion called for by the context. If a prosecutor, purporting to prove the defendant guilty of murder, shows on Iy that he had sufficient opportunity and Copi, Irving. Introduction to l~gic. 6th edition. New motive to commit the crime, he (the prosecutor) commits York: Macmillan, 19S2. x. 604 pp.ISBN o-02-324920-X the fallacy of insufficient conclusion. If, on the other hand, he succeeds only in "proving" that murder is a horrible crime, he is guilty of an ignoratio elenchi. In effect, then, The sixth edition of this widely used and influential text Copi does not distinguish between two different fal is worth reviewing, first. -

Discrete Mathematics, Chapter 1.4-1.5: Predicate Logic

Discrete Mathematics, Chapter 1.4-1.5: Predicate Logic Richard Mayr University of Edinburgh, UK Richard Mayr (University of Edinburgh, UK) Discrete Mathematics. Chapter 1.4-1.5 1 / 23 Outline 1 Predicates 2 Quantifiers 3 Equivalences 4 Nested Quantifiers Richard Mayr (University of Edinburgh, UK) Discrete Mathematics. Chapter 1.4-1.5 2 / 23 Propositional Logic is not enough Suppose we have: “All men are mortal.” “Socrates is a man”. Does it follow that “Socrates is mortal” ? This cannot be expressed in propositional logic. We need a language to talk about objects, their properties and their relations. Richard Mayr (University of Edinburgh, UK) Discrete Mathematics. Chapter 1.4-1.5 3 / 23 Predicate Logic Extend propositional logic by the following new features. Variables: x; y; z;::: Predicates (i.e., propositional functions): P(x); Q(x); R(y); M(x; y);::: . Quantifiers: 8; 9. Propositional functions are a generalization of propositions. Can contain variables and predicates, e.g., P(x). Variables stand for (and can be replaced by) elements from their domain. Richard Mayr (University of Edinburgh, UK) Discrete Mathematics. Chapter 1.4-1.5 4 / 23 Propositional Functions Propositional functions become propositions (and thus have truth values) when all their variables are either I replaced by a value from their domain, or I bound by a quantifier P(x) denotes the value of propositional function P at x. The domain is often denoted by U (the universe). Example: Let P(x) denote “x > 5” and U be the integers. Then I P(8) is true. I P(5) is false. -

The Comparative Predictive Validity of Vague Quantifiers and Numeric

c European Survey Research Association Survey Research Methods (2014) ISSN 1864-3361 Vol.8, No. 3, pp. 169-179 http://www.surveymethods.org Is Vague Valid? The Comparative Predictive Validity of Vague Quantifiers and Numeric Response Options Tarek Al Baghal Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Essex A number of surveys, including many student surveys, rely on vague quantifiers to measure behaviors important in evaluation. The ability of vague quantifiers to provide valid information, particularly compared to other measures of behaviors, has been questioned within both survey research generally and educational research specifically. Still, there is a dearth of research on whether vague quantifiers or numeric responses perform better in regards to validity. This study examines measurement properties of frequency estimation questions through the assessment of predictive validity, which has been shown to indicate performance of competing question for- mats. Data from the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), a preeminent survey of university students, is analyzed in which two psychometrically tested benchmark scales, active and collaborative learning and student-faculty interaction, are measured through both vague quantifier and numeric responses. Predictive validity is assessed through correlations and re- gression models relating both vague and numeric scales to grades in school and two education experience satisfaction measures. Results support the view that the predictive validity is higher for vague quantifier scales, and hence better measurement properties, compared to numeric responses. These results are discussed in light of other findings on measurement properties of vague quantifiers and numeric responses, suggesting that vague quantifiers may be a useful measurement tool for behavioral data, particularly when it is the relationship between variables that are of interest. -

Quantifying Aristotle's Fallacies

mathematics Article Quantifying Aristotle’s Fallacies Evangelos Athanassopoulos 1,* and Michael Gr. Voskoglou 2 1 Independent Researcher, Giannakopoulou 39, 27300 Gastouni, Greece 2 Department of Applied Mathematics, Graduate Technological Educational Institute of Western Greece, 22334 Patras, Greece; [email protected] or [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 July 2020; Accepted: 18 August 2020; Published: 21 August 2020 Abstract: Fallacies are logically false statements which are often considered to be true. In the “Sophistical Refutations”, the last of his six works on Logic, Aristotle identified the first thirteen of today’s many known fallacies and divided them into linguistic and non-linguistic ones. A serious problem with fallacies is that, due to their bivalent texture, they can under certain conditions disorient the nonexpert. It is, therefore, very useful to quantify each fallacy by determining the “gravity” of its consequences. This is the target of the present work, where for historical and practical reasons—the fallacies are too many to deal with all of them—our attention is restricted to Aristotle’s fallacies only. However, the tools (Probability, Statistics and Fuzzy Logic) and the methods that we use for quantifying Aristotle’s fallacies could be also used for quantifying any other fallacy, which gives the required generality to our study. Keywords: logical fallacies; Aristotle’s fallacies; probability; statistical literacy; critical thinking; fuzzy logic (FL) 1. Introduction Fallacies are logically false statements that are often considered to be true. The first fallacies appeared in the literature simultaneously with the generation of Aristotle’s bivalent Logic. In the “Sophistical Refutations” (Sophistici Elenchi), the last chapter of the collection of his six works on logic—which was named by his followers, the Peripatetics, as “Organon” (Instrument)—the great ancient Greek philosopher identified thirteen fallacies and divided them in two categories, the linguistic and non-linguistic fallacies [1]. -

Propositional Logic, Truth Tables, and Predicate Logic (Rosen, Sections 1.1, 1.2, 1.3) TOPICS

Propositional Logic, Truth Tables, and Predicate Logic (Rosen, Sections 1.1, 1.2, 1.3) TOPICS • Propositional Logic • Logical Operations • Equivalences • Predicate Logic Logic? What is logic? Logic is a truth-preserving system of inference Truth-preserving: System: a set of If the initial mechanistic statements are transformations, based true, the inferred on syntax alone statements will be true Inference: the process of deriving (inferring) new statements from old statements Proposi0onal Logic n A proposion is a statement that is either true or false n Examples: n This class is CS122 (true) n Today is Sunday (false) n It is currently raining in Singapore (???) n Every proposi0on is true or false, but its truth value (true or false) may be unknown Proposi0onal Logic (II) n A proposi0onal statement is one of: n A simple proposi0on n denoted by a capital leJer, e.g. ‘A’. n A negaon of a proposi0onal statement n e.g. ¬A : “not A” n Two proposi0onal statements joined by a connecve n e.g. A ∧ B : “A and B” n e.g. A ∨ B : “A or B” n If a connec0ve joins complex statements, parenthesis are added n e.g. A ∧ (B∨C) Truth Tables n The truth value of a compound proposi0onal statement is determined by its truth table n Truth tables define the truth value of a connec0ve for every possible truth value of its terms Logical negaon n Negaon of proposi0on A is ¬A n A: It is snowing. n ¬A: It is not snowing n A: Newton knew Einstein. n ¬A: Newton did not know Einstein. -

35. Logic: Common Fallacies Steve Miller Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Sexy Technical Communications Open Educational Resources 3-1-2016 35. Logic: Common Fallacies Steve Miller Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Cherie Miller Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/oertechcomm Part of the Technical and Professional Writing Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Steve and Miller, Cherie, "35. Logic: Common Fallacies" (2016). Sexy Technical Communications. 35. http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/oertechcomm/35 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sexy Technical Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Logic: Common Fallacies Steve and Cherie Miller Sexy Technical Communication Home Logic and Logical Fallacies Taken with kind permission from the book Why Brilliant People Believe Nonsense by J. Steve Miller and Cherie K. Miller Brilliant People Believe Nonsense [because]... They Fall for Common Fallacies The dull mind, once arriving at an inference that flatters the desire, is rarely able to retain the impression that the notion from which the inference started was purely problematic. ― George Eliot, in Silas Marner In the last chapter we discussed passages where bright individuals with PhDs violated common fallacies. Even the brightest among us fall for them. As a result, we should be ever vigilant to keep our critical guard up, looking for fallacious reasoning in lectures, reading, viewing, and especially in our own writing. None of us are immune to falling for fallacies.